The Haryana Police Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 1 | Page Item(S) Timeline Date Of

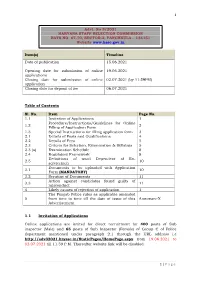

1 Advt. No 3/2021 HARYANA STAFF SELECTION COMMISSION BAYS NO. 67-70, SECTOR-2, PANCHKULA – 134151 Website www.hssc.gov.in Item(s) Timeline Date of publication 15.06.2021 Opening date for submission of online 19.06.2021 applications Closing date for submission of online 02.07.2021 (by 11:59PM) application Closing date for deposit of fee 06.07.2021 Table of Contents Sl. No. Item Page No. 1.1 Invitation of Applications 1 Procedure/Instructions/Guidelines for Online 1.2 2 Filling of Application Form 1.3 Special Instructions for filling application form 3 2.1 Details of Posts and Qualifications 4 2.2 Details of Fees 5 2.3 Criteria for Selection, Examination & Syllabus 5 2.3 (a) Examination Schedule 8 2.4 Regulatory Framework 8 Definitions of word Dependent of Ex- 2.5 10 servicemen Documents to be uploaded with Application 3.1 10 Form (MANDATORY) 3.2 Scrutiny of Documents 11 Action against candidates found guilty of 3.3 11 misconduct 4 Likely causes of rejection of application 1 The Punjab Police rules as applicable amended 5 from time to time till the date of issue of this Annexure-X Advertisement 1.1 Invitation of Applications Online applications are invited for direct recruitment for 400 posts of Sub inspector (Male) and 65 posts of Sub Inspector (Female) of Group C of Police department mentioned under paragraph 2.1 through the URL address i.e http://adv32021.hryssc.in/StaticPages/HomePage.aspx from 19.06.2021 to 02.07.2021 till 11.59 P.M. -

In the Supreme Court of India Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction Criminal Appeal No

[REPORTABLE] IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 2231 OF 2009 Satyavir Singh Rathi ….Appellant Versus State thr. C.B.I. ….Respondent WITH CRIMINAL APPEAL NOs.2476/2009, 2477-2483/2009 and 2484/2009. J U D G M E N T HARJIT SINGH BEDI, J. This judgment will dispose of Criminal Appeal Nos.2231 of 2009, 2476 of 2009 and 2477-2484 of 2009. The facts have been taken from Criminal Appeal No. 2231 of 2009 (Satyavir Singh Rathi vs. State thr. C.B.I.). On the 31st March 1997 Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh PW-11 both hailing from Kurukshetra in the State of Haryana came to Delhi to meet Pradeep Goyal in his office situated near the Mother Dairy Booth in Patparganj, Delhi. They reached the office premises between 12.00 noon and 1.00 Crl. Appeal No.2231/2009 etc. 2 p.m. but found that Pradeep Goyal was not present and the office was locked. Jagjit Singh thereupon contacted Pradeep Goyal on his Mobile Phone and was told by the latter that he would be reaching the office within a short time. Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh, in the meanwhile, decided to have their lunch and after buying some ice-cream from the Mother Dairy Booth, waited for Pradeep Goyal’s arrival. Pradeep Goyal reached his office at about 1.30 p.m. but told Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh that as he had some work at the Branch of the Dena Bank in Connaught Place, they should accompany him to that place. -

India's Police Complaints Authorities

India’s Police Complaints Authorities: A Broken System with Fundamental Flaws A Legal Analysis CHRI Briefing Paper September 2020 Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) is an independent, non-governmental, non- profit organisation headquartered in New Delhi, with offices in London, United Kingdom, and Accra, Ghana. Since 1987, it has worked for the practical realization of human rights through strategic advocacy and engagement as well as mobilization around these issues in Commonwealth countries. CHRI’s specialisation in the areas of Access to Justice (ATJ) and Access to Information (ATI) are widely known. The ATJ programme has focussed on Police and Prison Reforms, to reduce arbitrariness and ensure transparency while holding duty bearers to account. CHRI looks at policy interventions, including legal remedies, building civil society coalitions and engaging with stakeholders. The ATI looks at Right to Information (RTI) and Freedom of Information laws across geographies, provides specialised advice, sheds light on challenging issues, processes for widespread use of transparency laws and develops capacity. CHRI reviews pressures on freedom of expression and media rights while a focus on Small States seeks to bring civil society voices to bear on the UN Human Rights Council and the Commonwealth Secretariat. A growing area of work is SDG 8.7 where advocacy, research and mobilization is built on tackling Contemporary Forms of Slavery and human trafficking through the Commonwealth 8.7 Network. CHRI has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council and is accredited to the Commonwealth Secretariat. Recognised for its expertise by governments, oversight bodies and civil society, it is registered as a society in India, a trust in Ghana, and a public charity in the United Kingdom. -

I. INTRODUCTION the Police Personnel Have a Vital Role in a Parliamentary Democracy

Bureau of Police Research & Development I. INTRODUCTION The police personnel have a vital role in a parliamentary democracy. The society perceives them as custodians of law and order and providing safety and security to all. This essentially involves continuous police-public interface. The ever changing societal situation in terms of demography, increasing rate and complexity of crime particularly of an organized nature and also accompanied by violence, agitations, violent demonstrations, variety of political activities, left wing terrorism, insurgency, militancy, enforcement of economic and social legislations, etc. have further added new dimensions to the responsibilities of police personnel. Of late, there has been growing realization that police personnel have been functioning with a variety of constraints and handicaps, reflecting in their performance, thus becoming a major concern for both central and state governments. In addition, there is a feeling that the police performance has been falling short of public expectations, which is affecting the overall image of the police in the country. With a view to making the police personnel more effective and efficient especially with reference to their, professionalism and public interface several initiatives have been launched from time to time. The Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India, the Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPR&D), the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the SVP National Police Academy (NPA) have initiated multi- pronged strategies for the overall improvement in the functioning of police personnel. The major focus is on, to bring about changes in the functioning of police personnel to basically align their role with the fast changing environment. -

Police Odganisation in India

POLICE ORGANISATION IN INDIA i Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) is an independent, non-partisan, international non-governmental organisation, mandated to ensure the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth. In 1987, several Commonwealth professional associations founded CHRI. They believed that while the Commonwealth provided member countries a shared set of values and legal principles from which to work and provided a forum within which to promote human rights, there was little focus on the issues of human rights within the Commonwealth. CHRI’s objectives are to promote awareness of and adherence to the Commonwealth Harare Principles, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other internationally recognised human rights instruments, as well as domestic instruments supporting human rights in Commonwealth Member States. Through its reports and periodic investigations, CHRI continually draws attention to progress and setbacks to human rights in Commonwealth countries. In advocating for approaches and measures to prevent human rights abuses, CHRI addresses the Commonwealth Secretariat, Member Governments and civil society associations. Through its public education programmes, policy dialogues, comparative research, advocacy and networking, CHRI’s approach throughout is to act as a catalyst around its priority issues. CHRI is based in New Delhi, India, and has offices in London, UK and Accra, Ghana. International Advisory Commission: Yashpal Ghai - Chairperson. Members: Clare Doube, Alison Duxbury, Wajahat Habibullah, Vivek Maru, Edward Mortimer, Sam Okudzeto and Maja Daruwala. Executive Committee (India): Wajahat Habibullah – Chairperson. Members: B. K. Chandrashekar, Nitin Desai, Sanjoy Hazarika, Kamal Kumar, Poonam Muttreja, Ruma Pal, Jacob Punnoose, A P Shah and Maja Daruwala - Director. -

India's Internal Security Apparatus Building the Resilience Of

NOVEMBER 2018 Building the Resilience of India’s Internal Security Apparatus MAHENDRA L. KUMAWAT VINAY KAURA Building the Resilience of India’s Internal Security Apparatus MAHENDRA L. KUMAWAT VINAY KAURA ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mahendra L. Kumawat is a former Special Secretary, Internal Security, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India; former Director General of the Border Security Force (BSF); and a Distinguished Visitor at Observer Research Foundation. Vinay Kaura, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the Department of International Affairs and Security Studies, Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Rajasthan. He is also the Coordinator at the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies in Jaipur. ([email protected]) Attribution: Mahendra L. Kumawat and Vinay Kaura, 'Building the Resilience of India's Internal Security Apparatus', Occasional Paper No. 176, November 2018, Observer Research Foundation. © 2018 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. Building the Resilience of India’s Internal Security Apparatus ABSTRACT 26 November 2018 marked a decade since 10 Pakistan-based terrorists killed over 160 people in India’s financial capital of Mumbai. The city remained under siege for days, and security forces disjointedly struggled to improvise a response. The Mumbai tragedy was not the last terrorist attack India faced; there have been many since. After every attack, the government makes lukewarm attempts to fit episodic responses into coherent frameworks for security-system reforms. Yet, any long-term strategic planning, which is key, remains absent. -

Advertisement No. 3/2021

1 HARYANA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION BAYS NO 1-10, BLOCK-B, SECTOR - 4, PANCHKULA ADVERTISEMENT NO. 3/2021 Item (s) Timeline Date of publication 26.02.2021 Opening date for submission of online applications 03.03.2021 Closing date for submission of online applications 02.04.2021 (The Commission‘s Website: www.hpsc.gov.in) IMPORTANT 1. CANDIDATES TO ENSURE THEIR ELIGIBILITY FOR THE EXAMINATION: The Candidates applying for the examination should ensure that they fulfill all eligibility conditions for admission to the examination. Their admission to all the stages of the examination will be purely provisional subject to satisfying the prescribed eligibility conditions. Mere issue of e-Admit Card to the candidate will not imply that his/her candidature has been finally cleared by the Commission. The Commission takes up verification of eligibility conditions with reference to original documents only after the candidate has qualified for Main Written Examination / Interview / Personality Test. Note: The decision of the Commission with regards to the eligibility or otherwise of a candidate, for admission to the Examination, shall be final. 2. HOW TO APPLY: Candidates are required to apply online on the website http://hpsc.gov.in/en- us/. Detailed instructions for filling up online applications are available on the above mentioned website. No other means / mode of submission of application will be accepted. 3. LAST DATE FOR RECEIPT OF APPLICATIONS: The online Applications can be submitted up to 02.04.2021 till 11:55 PM. The eligible candidates shall be issued an e-Admit Card well before the commencement of the Examination. -

The Indian Police Journal the Indian Police Journal Vol

RNI No. 4607/57 Vol. 65 No. 4 Vol. ISSN 0537-2429 The Indian Police October-December 2018 October-December Journal Published by: The Bureau of Police Research & Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India Vol. 65 No. 4 ISSN 0537-2429 October-December 2018 New Building, National Highway-8, Mahipalpur, New Delhi - 110037 BPRDIndia bprdindia officialBPRDIndia Bureau of Police Research & Development India www.bprd.nic.in Printied at: India Offset Press, New Delhi - 110064 The Indian Police Journal The Indian Police Journal Vol. 65 No. 4 October-December 2018 Vol. 65 No. 4 October-December 2018 Board Of ReVIewers 1. Shri R.K. Raghavan, IPS (Retd.) 13. Prof. Ajay Kumar Jain Note for Contribution Former Director, CBI B-1, Scholar Building, Management Development Institute, Mehrauli Road, 2. Shri P.M. Nair Sukrali The Indian Police Journal (IPJ) is the oldest police journal of the country. It is being Chair Prof. TISS, Mumbai published since 1954. It is the flagship journal of Bureau of Police Research and 14. Shri Balwinder Singh 3. Shri Vijay Raghawan Former Special Director, CBI Development (BPRD), MHA, which is published every quarter of the year. It is Prof. TISS, Mumbai Former Secretary, CVC circulated through hard copy as well as e-book format. It is circulated to Interpol 4. Shri N. Ramachandran countries and other parts of the world. IPJ is peer reviewed journal featuring various 15. Shri Nand Kumar Saravade President, Indian Police Foundation. CEO, Data Security Council of India matters and subjects relating to policing, internal security and allied subjects. Over New Delhi0110017 the years it has evolved as academic journal of the Indian Police providing critical 16. -

To Download Document for More Info

HARYANA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION BAYS NO. 1-10, BLOCK-B, SECTOR-4, PANCHKULA INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES (For the post of Assistant Engineer (Electrical), Class-II (General) Advt. No. 3 (1) Date of Publication: 17.11.2015 The Commission invites online applications for recruitment of 01 post of Assistant Engineer (Electrical), Class-II (General) in Haryana Police Housing Corporation Limited, Panchkula. 1. Closing date for the submission of applications online : 16.12.2015 2. Closing date for deposit of cost of application form including Examination fees in all branches of State bank of India & State Bank of Patiala. : 19.12.2015 up to 4:00 PM. 3. Closing date for receiving printed application form alongwith documents in support of the claim in Commission’s office: 04.01.2016 upto 05:00 P.M. and for the applicants from Forward Remote Areas i.e. States/Union Territories of North–East Region, Lakshadweep, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Sikkim, Ladakh Region of Jammu & Kashmir and Pangi Sub-Division of Himachal Pradesh:- 11.01.2016 upto 05.00 P.M. 1. Essential Qualifications:- i) Degree in Electrical Engineering from a recognized University or one of the other qualifications in Electrical Engineering as specified in appendix B of Punjab Service of Engineers, Class-II, PWD B&R Branch Rules, 1965. Provided that Degree obtained through correspondence or distance education mode from Universities/Deemed Universities/Technical Institutions is valid qualification for initial recruitment only if such Degree programme of technical education conducted through distance education mode has been approved by the joint Committee of UGC-AICTE-DEC as clarified by the Govt. -

Punjab Police Rule Volume

1 THE PUNJAB POLICE RULES, 1934 (As applicable In Haryana State) ------------ Issued by and with the authority of the Provincial Government Under section 7 and 12 of Act V of 1861 _________ Volume III (Reprint Edition—1980) (Amended as per correction slips issued by Punjab Government up to 31 st October 1966 and Haryana Government up to 31 st December 1980) 2 CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. CHAPTER -XXI Preventive and detective organization 10-40 CHAPTER -XXII Police Stations 67-119 CHAPTER -XXIII Prevention of offences 166-195 CHAPTER -XXIV Information to the Police 236-257 CHAPTER -XXV Investigation 270-315 CHAPTER -XXVI Arrest, escape and custody 362-381 CHAPTER -XXVII Prosecution and Court duties 411-445 CHAPTER -XXVIII Railway Police and other special rules 473-479 3 LIST OF APPENDICES Volume III SUBJECT PAGES 21.18 (1) Subjects to be discussed in the Criminal Tribes Reports 41-42 21.35(2) Instruction concerning the examination of the scenes of their 43-47 and burglaries and particulars required to be submitted in cases of all such offences to the Central Investigating Agency. 22.20 Rules relating to cattle pounds 115-119 22.26 Instructions for Collectors and Deputy Commissioners with 120-127 regard to troops marching through districts, and rules for the supply of carriages by the Civil authorities. 22.68(2) Powers and duties of Police Officers under the Indian Arms 128-138 Act, Excise Laws, Explosives Act, Petroleum Act, Poisons Act and Sarais Act. 23.39(1) Surveillance over convicts released under section 565, 196-201 Criminal Procedure Code. -

Report-Of-Pay

Index Ch. No. Contents Page No. 1 Foreword - 1.1 Constitution of Pay Anomalies Commission & its 1 Terms of Reference 2.1 Representations received and considered by the 8 Commission and its recommendations thereon 2.2 Agriculture Department 8 2.3 Animal Husbandry & Dairying Department 18 2.4 Architecture Department 33 2.5 Chief Secretary To Government Haryana 34 (Political And Parliamentary Affairs) 2.6 Cooperation Department 35 2.7 Development & Panchayat Department 38 2.8 Election Department 43 2.9 Employment Department 44 2.10 Environment Department 45 2.11 Excise & Taxation Department 46 2.12 Finance & Planning Department 55 2.13 Fisheries Department 60 2.14 Food & Supplies Department 62 2.15 Forest Department 64 2.16 Haryana Civil Secretariat 67 2.17 Haryana Vidhan Sabha Secretariat 73 2.18 Health Department 76 2.19 Higher Education Department 97 2.20 Home Department 100 2.21 Horticulture Department 109 2.22 Hospitality Department 111 2.23 Industrial Training Department 114 2.24 Industries & Commerce Department 117 2.25 Information, Public Relation & Cultural Affairs 120 Department 2.26 Labour Department 127 2.27 Law & Legislative Department 130 2.28 Medical Education & Research Department 132 2.29 Mines & Geology Department 133 2.30 PWD three wings (PWD (B&R), Irrigation and 134 PHED) 2.31 Panchayati Raj Department 176 2.32 Rajya Sainik Board 177 2.33 Renewable Energy 178 2.34 Revenue & Disaster Management Department 179 2.35 Rural Development Department 184 2.36 School Education Department 185 2.37 Social Justice & Empowerment Department 189 2.38 Sports and Youth Affairs Department 190 2.39 State Election Commission 191 2.40 Technical Education Department 192 2.41 Tourism Department 195 2.42 Town & Country Planning Department 196 2.43 Transport Department 197 2.44 Urban Local Bodies Department 200 2.45 Welfare of SCs & BCs Department 201 2.46 Women & Child Development Department 203 2.46 Haryana Karamchari Maha Sangh and Sarv 204 Karamchari Sangh, Haryana. -

Revenue and Disaster Management Department Government Of

Railway Station Safety Initiative By Revenue and Disaster Management Department Government of Haryana RAILWAY STATION DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN Railway Junction, Jind 2014-15 CENTRE FOR DISASTER MANAGEMENT HARYANA INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, GURGAON INDEX 1. Disaster Management in Indian Railways 2. Railway Station Profile 2.1. Possible Hazards 2.2. Identification of Potential Non-Structural Hazards 2.3. Resource Inventory 2.4. Nearest resources 2.5. List of hospitals for emergency management 2.6. List of blood banks 3. Response Mechanism 4. Mock Drill 5. Assessment check list 6. Emergency mock drill reporting format 2 1. Disaster Management in Indian Railways “Railway Disaster is a serious train accident or an untoward event of grave nature, either on railway premises or arising out of railway activity, due to natural or man-made causes, that may lead to loss of many lives and/or grievous injuries to a large number of people, and/or severe disruption of traffic etc, necessitating large scale help from other Government/Non-government and Private Organizations.” The Indian Railways is the world’s largest government railway. It is a single system which consists of 65,436 route km of track that criss cross the country, on which more than 20,238 number of trains ply, carrying about 23 million passengers and hauling nearly 2.77 million tonnes of freight every day. Therefore, the safety of operations on the Railways and the safety and security of the millions availing the services of the Railways are of paramount importance. India is vulnerable, in varying degrees, to a large number of natural as well as man-made disasters.