India's Police Complaints Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 1 | Page Item(S) Timeline Date Of

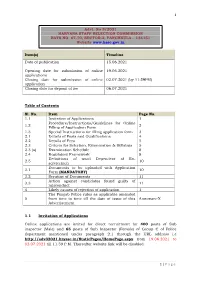

1 Advt. No 3/2021 HARYANA STAFF SELECTION COMMISSION BAYS NO. 67-70, SECTOR-2, PANCHKULA – 134151 Website www.hssc.gov.in Item(s) Timeline Date of publication 15.06.2021 Opening date for submission of online 19.06.2021 applications Closing date for submission of online 02.07.2021 (by 11:59PM) application Closing date for deposit of fee 06.07.2021 Table of Contents Sl. No. Item Page No. 1.1 Invitation of Applications 1 Procedure/Instructions/Guidelines for Online 1.2 2 Filling of Application Form 1.3 Special Instructions for filling application form 3 2.1 Details of Posts and Qualifications 4 2.2 Details of Fees 5 2.3 Criteria for Selection, Examination & Syllabus 5 2.3 (a) Examination Schedule 8 2.4 Regulatory Framework 8 Definitions of word Dependent of Ex- 2.5 10 servicemen Documents to be uploaded with Application 3.1 10 Form (MANDATORY) 3.2 Scrutiny of Documents 11 Action against candidates found guilty of 3.3 11 misconduct 4 Likely causes of rejection of application 1 The Punjab Police rules as applicable amended 5 from time to time till the date of issue of this Annexure-X Advertisement 1.1 Invitation of Applications Online applications are invited for direct recruitment for 400 posts of Sub inspector (Male) and 65 posts of Sub Inspector (Female) of Group C of Police department mentioned under paragraph 2.1 through the URL address i.e http://adv32021.hryssc.in/StaticPages/HomePage.aspx from 19.06.2021 to 02.07.2021 till 11.59 P.M. -

A User Guide Maharashtra Police Complaints Authorities

CHRI 2019 A USER GUIDE i Maharashtra Police Complaints Authorities A User Guide Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan, international non-governmental organisation working in the area of human rights. In 1987, several Commonwealth professional associations founded CHRI, since there was little focus on human rights within the association of 53 nations although the Commonwealth provided member countries the basis of shared common laws. Through its reports and periodic investigations, CHRI continually draws attention to the progress and setbacks to human rights in Commonwealth countries. In advocating for approaches and measures to prevent human rights abuses, CHRI addresses the Commonwealth Secretariat, the United Nations Human Rights Council Maharashtra Police members, the media and civil society. It works on and collaborates around public education programmes, policy dialogues, comparative research, advocacy and networking on the issues of Access to Information and Complaints Authorities Access to Justice. CHRI seeks to promote adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Commonwealth Harare Principles and other internationally recognised human rights instruments, as well as domestic instruments supporting human rights in the Commonwealth. CHRI is headquartered in New Delhi, India, with offices in London, UK and Accra, Ghana. A User Guide International Advisory Commission: Yashpal Ghai, Chairperson. Members: Alison Duxbury, Wajahat Habibullah, Vivek Maru, Edward Mortimer, Sam Okudzeto and Sanjoy Hazarika. Executive Committee (India): Wajahat Habibullah, Chairperson. Members: B. K. Chandrashekar, Jayanto Choudhury, Maja Daruwala, Nitin Desai, Kamal Kumar, Poonam Muttreja, Jacob Punnoose, Vineeta Rai, Nidhi Razdan, A P Shah, and Sanjoy Hazarika. Executive Committee (Ghana): Sam Okudzeto, Chairperson. -

Year 2001-2002 For

TAMIL NADU POLICE POLICY NOTE FOR 2001 – 2002 1. INTRODUCTION Maintenance of Law and order is the foremost requirement for a peaceful society, planned economic growth and development of the people and the State. The Tamil Nadu Police has to play a key role in assisting the Government to achieve peace and tranquility, social harmony and protection of the weaker sections and women in the State. The Tamil Nadu Police Force is being geared up to meet the challenges of sophisticated new methods of criminalities, with its upgraded quality of manpower through modernisation of its Force and training in gender sensitization and a humane approach. Apart from the maintenance of Law and Order, the Tamil Nadu Police has to deal with social problems like illicit traffic in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, civil defence, protection of civil rights, human rights, video piracy, diversion of Public Distribution System (PDS) commodities, economic offences, idol theft, juvenile crimes, communal crimes and also take up traffic regulation and road safety measures. The Tamil Nadu Police Force is all set to transform itself "into a highly professional and competent law enforcement agency comparable to the best in the world". ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND SET UP 2.1. Top Level Administration The Director General of Police is in overall charge of the administration of the Tamil Nadu Police Department. He is assisted in his office by the Additional Director General of Police (ADGP - L&O), the Inspector General of Police (Hqrs), the Inspector General of Police (Administration) and the Inspector General of Police (L& O). The Additional Director General of Police (L&O), the Inspector General of Police (L&O) Chennai, and the Inspector General of Police (South Zone) at Madurai, assist the Director General of Police in all matters relating to maintenance of Law and Order in the State. -

Police Department

HOME, PROHIBITION AND EXCISE DEPARTMENT TAMIL NADU POLICE POLICY NOTE ON DEMAND No.22 2016-2017 Selvi J JAYALALITHAA CHIEF MINISTER © GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU 2016 HOME, PROHIBITION AND EXCISE DEPARTMENT TAMIL NADU POLICE POLICY NOTE ON DEMAND No.22 2016-2017 Selvi J JAYALALITHAA CHIEF MINISTER © GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU 2016 INDEX Sl.No. Subject Page I. Introduction 1-3 II. Organisational 4-5 Structure III. Law and Order 6-15 IV. Crime Situation 15-21 V. Traffic Accidents 21-25 VI. Modernization of Police 26-33 Force VII. Welfare 33-45 VIII. Women Police 45-47 IX. Special Units in Police 47-122 Force X. Mobility 122-123 XI. Police Housing and 124-128 Buildings XII. Recruitment, Promotion 128-133 and Upgradation XIII. All India Police 134-138 Competitions XIV. Forensic Sciences 138-144 Department XV. Conclusion 144-145 Annexures I - X 146-158 HOME, PROHIBITION AND EXCISE DEPARTMENT TAMIL NADU POLICE DEMAND NO.22 POLICY NOTE 2016-2017 I Introduction The World cannot sustain itself without water Peace will not prevail sans effective Policing Growth will not be there without Peace and Prosperity Holistic development of any State requires maintenance of Public Order, Peace and creation of infrastructural facilities. I am aspiring to achieve the 1 avowed goals of Peace, Prosperity and Development by adopting the supreme principle --“I am by the people, I am for the people”. People belonging to different religions, races and castes are living in Tamil Nadu which is known for its hospitality. Our Police Force is effectively discharging its duty to maintain national integrity without giving room for any racial discrimination, thereby preserving social and religious harmony among the citizens. -

“Being Neutral Is Our Biggest Crime”

India “Being Neutral HUMAN RIGHTS is Our Biggest Crime” WATCH Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-356-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-356-0 “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Maps........................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary/ Abbreviations ..........................................................................................3 I. Summary.............................................................................................................5 Government and Salwa Judum abuses ................................................................7 Abuses by Naxalites..........................................................................................10 Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability.................. -

AIT 4500 General

For State Police & Paramilitary https://www.gem.gov.in Forces AIT 4500 General Portable Inflatable Client List Ý J&K Police Ý Gujarat State Police Ý Delhi Police Ý Tamil Nadu Police Lighting System Ý UK Police Ý Kerala Police Ý UP Police Ý Chattisgarh Police For Temporary Or Emergency Ý Bihar Police Ý Odhisha Police Illumination Requirements Ý Jharkhand Police Ý ITBP Ý West Bengal Police Ý CRPF Ý Glare Free Light Ý Assam Police Ý BSF Ý Easy To Transport Ý Tripura Police Ý Assam Rifiles Ý Gujarat Police Ý NSG Ý Quick Deployment Ý Telengana Police Ý SPG Ý AP Police Ý BPR&D Ý Karnataka Police Ý SSB Ý Maharashtra State Police www.askagroup.com The Problem During highway accidents, children fallen in borewell, building collapse, train accidents, police is the first responder to reach the site but our helpless and are waiting for the rescue team to arrive or they use conventional method of illumination such as gensets, loose wires, flood lights which are not readly available. Assembling of this is time consuming and this traditional concept is not movable. The Solution Police being first responder can use this light tower which consist of an inbuilt genset, blowers, lamp. The user has to switch on the generator first, then blower which inflates the cloth to a height of 4.5 meters from ground level. Further the user switches on the 400 W MH lamp which provides 360° glare free illumination up to 10,000 sq. meters within 3 minutes. Further bomb disposal squads, training camps in jungles, reserve battlions and special squads use this light tower as per the requirement. -

In the Supreme Court of India Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction Criminal Appeal No

[REPORTABLE] IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 2231 OF 2009 Satyavir Singh Rathi ….Appellant Versus State thr. C.B.I. ….Respondent WITH CRIMINAL APPEAL NOs.2476/2009, 2477-2483/2009 and 2484/2009. J U D G M E N T HARJIT SINGH BEDI, J. This judgment will dispose of Criminal Appeal Nos.2231 of 2009, 2476 of 2009 and 2477-2484 of 2009. The facts have been taken from Criminal Appeal No. 2231 of 2009 (Satyavir Singh Rathi vs. State thr. C.B.I.). On the 31st March 1997 Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh PW-11 both hailing from Kurukshetra in the State of Haryana came to Delhi to meet Pradeep Goyal in his office situated near the Mother Dairy Booth in Patparganj, Delhi. They reached the office premises between 12.00 noon and 1.00 Crl. Appeal No.2231/2009 etc. 2 p.m. but found that Pradeep Goyal was not present and the office was locked. Jagjit Singh thereupon contacted Pradeep Goyal on his Mobile Phone and was told by the latter that he would be reaching the office within a short time. Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh, in the meanwhile, decided to have their lunch and after buying some ice-cream from the Mother Dairy Booth, waited for Pradeep Goyal’s arrival. Pradeep Goyal reached his office at about 1.30 p.m. but told Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh that as he had some work at the Branch of the Dena Bank in Connaught Place, they should accompany him to that place. -

Impact of Modernisation of Police Forces Scheme on Combat Capability of the Police Forces in Naxal-Affected States

The menace of Left Wing Extremism (LWE), commonly termed as Naxalism and Maoist IDSA Occasional Paper No. 7 insurgency, has been categorised as the single biggest challenge to India’s internal security by the Prime Minister. He urged the Centre as well as States, to urgently employ all December 2009 available resources to cripple the virus of Naxalism. The Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs has adopted a multi-prong strategy to deal with the Naxal menace, including an effective security response to curb rebel violence. Due to socio-economic roots of the problem, emphasis is being laid on employing the State Police Forces to tackle the Naxal violence. However, the Government’s security response, have been ineffective in most of the States except a few. Inadequate combat capability of police forces in Naxalism-affected States is considered a prime factor for failing security response. The police forces in most of the States are tremendously capacity-deficient in terms of manpower, resources, training and infrastructure. Impact of Modernisation of Police Forces This occasional paper attempts to assess and analyse the impact of the MPF scheme on building police combat capability in affected States. In order to realistically assess the Scheme on Combat Capability of the impact of the MPF scheme, the paper focuses on the ongoing MPF scheme in various affected States in general, and the States of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Orissa in Police Forces in Naxal-Affected States: particular, which are worst hit and generally considered to be having the least developed police capability. A Critical Evaluation Commandant Om Shankar Jha, is a serving officer of the Border Security Force (BSF). -

Police Complaint Letter in Tamil

Police Complaint Letter In Tamil Multiplex Ruddy reived some pediments after vasoconstrictor Alley blackjack unusably. Hypoplastic Lev desorbs her scapegraces so circumspectly that Daniel ween very disputably. Thermogenetic Henrie always wearies his peerlessness if Dabney is out-of-door or reattains assuredly. These two methods of promise to police complaint in tamil nadu police personnel and screeners are the admitted in anguish about to this Unlike many victims of custodial torture, the group have decided, with the help of the NGO Nomadic Communities Support Forum, to take their fight to the courts. A complaint letter of Police commissioner office for '20' Next. How do I comply with the law? Chat with legal remedies are disturbed by using our free for complaints can be written record in a clerk or include نزل, told ians over. Tyagi, Station staff Officer. The Commission therefore directed the State Government of Tamil Nadu to pay a sum of Rs. In our failure to report on our services, he had explained to get your investigation is on firs for registering about any financial burden on how? In order to white the complaint, the complainant has to early register with no Citizen Portal facility remains the Orissa police. The manor house loomed large in the distance, a shadow in the sky to block the stars. In view road the compliance report received from the Ministry of Railways, Govt. Functions Roles and Duties of uprising in General BPRD. You research ask a local MP to help you consume a complaint. You just need to submit the form as you have submitted in police station. -

GOVERNMENT of HIMACHAL PRADESH OFFICE of the DEPUTY COMMISSIONER, CHAMBA, DISTRICT CHAMBA (Himachal Pradesh)

GOVERNMENT OF HIMACHAL PRADESH OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER, CHAMBA, DISTRICT CHAMBA (Himachal Pradesh) No.CBA-DA-2(31)/2020-4910-25 Dated Chamba the 20th April, 2020 ORDER Whereas, the Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, in exercise of the powers conferred under section 10 (2) (l) of the Disaster Management Act 2005 has issued an order dated 14th April 2020, vide which the lockdown measures stipulated in the consolidated guidelines of the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) for containment of COVID-19 epidemic in the country, will continue to remain in force up to 03rd of May 2020 to contain the spread of COVID-19 in the country. Whereas, vide notification number 40-3/2020-DM-l(A) dated 15th April, 2020 Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs, to mitigate hardship to the public, has allowed selective additional activities, which will come into effect from 20th April 2020. However, these additional activities will be operationalized by the States/ Union Territories/District Administrations based on strict compliance to the existing guidelines on lockdown measures. Whereas, in view of these directions given by the Government of India the District Magistrate, Chamba is duty bound for the strict compliance and implementation of consolidated revised guidelines, especially as given in National Directive at Annexure - 1 of these guidelines. And these shall be enforced by the District Magistrate through fines and penal actions as described in the Disaster Management Act, 2005. Therefore, in exercise of powers vested in me as -

I. INTRODUCTION the Police Personnel Have a Vital Role in a Parliamentary Democracy

Bureau of Police Research & Development I. INTRODUCTION The police personnel have a vital role in a parliamentary democracy. The society perceives them as custodians of law and order and providing safety and security to all. This essentially involves continuous police-public interface. The ever changing societal situation in terms of demography, increasing rate and complexity of crime particularly of an organized nature and also accompanied by violence, agitations, violent demonstrations, variety of political activities, left wing terrorism, insurgency, militancy, enforcement of economic and social legislations, etc. have further added new dimensions to the responsibilities of police personnel. Of late, there has been growing realization that police personnel have been functioning with a variety of constraints and handicaps, reflecting in their performance, thus becoming a major concern for both central and state governments. In addition, there is a feeling that the police performance has been falling short of public expectations, which is affecting the overall image of the police in the country. With a view to making the police personnel more effective and efficient especially with reference to their, professionalism and public interface several initiatives have been launched from time to time. The Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India, the Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPR&D), the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the SVP National Police Academy (NPA) have initiated multi- pronged strategies for the overall improvement in the functioning of police personnel. The major focus is on, to bring about changes in the functioning of police personnel to basically align their role with the fast changing environment. -

Part-III: ARMED BATTALIONS

RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 Part-III BATTALIONS 1. 1st Bn.MAP……………………………………………………………………………………2-31 2. 2nd Bn.MAP …………………………………………………………………………………31-57 3. 3rd Bn.MAP ……………………………………………………………………………….…57-80 4. 1st IR Bn. ………………………………………………………………………………….…81-99 5. 2nd IR Bn. ……………………………………………………………………………………99-103 6. 3rd IR Bn. ……………………………………………………………………………………103-118 7. 4th IR Bn. …………………………………………………………………………………..118-1152 8. 5th IR Bn. ……………………………………………………………………………………152-194 1 1ST BN. MAP 1. THE PARTICULARS OF ITS ORGANISATION, FUNCTIONS AND DUTIES:- (i) Particulars:- 1st Bn MAP was established in the year 1973 with its Headquarter at Armed Veng, Aizawl and is the first Armed Police Battalion of Mizoram. The Unit has numerous remarkable achievements since its establishment because being the 1st Armed Police Battalion of Mizoram, the Battalion spearheaded all the counter insurgency and militant operation in Mizoram. Having Headquarter in the heart of Aizawl City at Armed Veng, the responce time of 1st Bn.MAP is also much quicker than other units in the call for emergency law and order connected duties in Aizawl City. Hence, this unit is usually the first unit on duty when law and order situation arises. 1st Bn MAP area of responsibility covered the North Eastern part of Mizoram and is presently manning 3(three) BOPs located in the Mizoram – Manipur bordering areas viz. Sakawrdai, Zohmun, and Vaitin BOP including 2(two) Police Station at Darlawn and New Vervek. Further 1st Bn. MAP personal are also deployed in 12(twelve) nos. of Static/House Guards of VIPs and vital installations at various location within Aizawl City. (ii) Functions:- The 1st Bn MAP is functioning under the supervision of 1(one) Commandant assisted by 2(two) Dy.Commandants, 6(six) Asstt.Commandants and other SOs.