India's Internal Security Apparatus Building the Resilience Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations TABLE of CONTENTS Foreword / Messages the Police Division in Action

United Nations United Department of Peacekeeping Operations of Peacekeeping Department 12th Edition • January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword / Messages The Police Division in Action 01 Foreword 22 Looking back on 2013 03 From the Desk of the Police Adviser From many, one – the basics of international 27 police peacekeeping Main Focus: Une pour tous : les fondamentaux de la 28 police internationale de maintien Vision and Strategy de la paix (en Français) “Police Week” brings the Small arms, big threat: SALW in a 06 30 UN’s top cops to New York UN Police context 08 A new vision for the UN Police UNPOL on Patrol Charting a Strategic Direction 10 for Police Peacekeeping UNMIL: Bringing modern forensics 34 technology to Liberia Global Effort Specific UNOCI: Peacekeeper’s Diary – 36 inspired by a teacher Afghan female police officer 14 literacy rates improve through MINUSTAH: Les pompiers de Jacmel mobile phone programme 39 formés pour sauver des vies sur la route (en Français) 2013 Female Peacekeeper of the 16 Year awarded to Codou Camara UNMISS: Police fingerprint experts 40 graduate in Juba Connect Online with the 18 International Network of UNAMID: Volunteers Work Toward Peace in 42 Female Police Peacekeepers IDP Camps Facts, figures & infographics 19 Top Ten Contributors of Female UN Police Officers 24 Actual/Authorized/Female Deployment of UN Police in Peacekeeping Missions 31 Top Ten Contributors of UN Police 45 FPU Deployment 46 UN Police Contributing Countries (PCCs) 49 UN Police Snap Shot A WORD FROM UNDER-SECRETARY-GENERAL, DPKO FOREWORD The changing nature of conflict means that our peacekeepers are increasingly confronting new, often unconventional threats. -

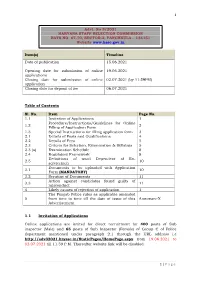

1 1 | Page Item(S) Timeline Date Of

1 Advt. No 3/2021 HARYANA STAFF SELECTION COMMISSION BAYS NO. 67-70, SECTOR-2, PANCHKULA – 134151 Website www.hssc.gov.in Item(s) Timeline Date of publication 15.06.2021 Opening date for submission of online 19.06.2021 applications Closing date for submission of online 02.07.2021 (by 11:59PM) application Closing date for deposit of fee 06.07.2021 Table of Contents Sl. No. Item Page No. 1.1 Invitation of Applications 1 Procedure/Instructions/Guidelines for Online 1.2 2 Filling of Application Form 1.3 Special Instructions for filling application form 3 2.1 Details of Posts and Qualifications 4 2.2 Details of Fees 5 2.3 Criteria for Selection, Examination & Syllabus 5 2.3 (a) Examination Schedule 8 2.4 Regulatory Framework 8 Definitions of word Dependent of Ex- 2.5 10 servicemen Documents to be uploaded with Application 3.1 10 Form (MANDATORY) 3.2 Scrutiny of Documents 11 Action against candidates found guilty of 3.3 11 misconduct 4 Likely causes of rejection of application 1 The Punjab Police rules as applicable amended 5 from time to time till the date of issue of this Annexure-X Advertisement 1.1 Invitation of Applications Online applications are invited for direct recruitment for 400 posts of Sub inspector (Male) and 65 posts of Sub Inspector (Female) of Group C of Police department mentioned under paragraph 2.1 through the URL address i.e http://adv32021.hryssc.in/StaticPages/HomePage.aspx from 19.06.2021 to 02.07.2021 till 11.59 P.M. -

Policy Guidance on Support to Policing in Developing Countries

POLICY GUIDANCE ON SUPPORT TO POLICING IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Ian Clegg, Robert Hunt and Jim Whetton November 2000 Centre for Development Studies University of Wales, Swansea Swansea SA2 8PP [email protected] http://www.swansea.ac.uk/cds ISBN 0 906250 617 Policy Guidance on Support to Policing in Developing Countries ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful for the support of the Department for International Development, (DFID), London, who funded this work for the benefit of developing/ transitional countries. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of DFID. It was initially submitted to DFID in November 1999 as a contribution to their policy deliberations on Safety, Security and Accessible Justice. It is now being published more widely in order to make it available to countries and agencies wishing to strengthen programmes in this field. At the same time, DFID are publishing their general policy statement on SSAJ, (DFID, 2000). Our work contributes to the background material for that statement. We are also most grateful to the authors of the specially commissioned papers included as Annexes to this report, and to the police advisers and technical cooperation officers who contributed to the survey reported in Annex B. It will be obvious in the text how much we are indebted to them all. This report is the joint responsibility of the three authors. However, Ian Clegg and Jim Whetton of CDS, University of Wales, Swansea, would like to express personal thanks to co-author Robert Hunt, OBE, QPM, former Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, London, for contributing his immense practical experience of policing and for analysing the survey reported in Annex B. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs Rajya Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO.*318 TO BE ANSWERED ON THE 17TH DECEMBER, 2014/AGRAHAYANA 26, 1936 (SAKA) STEPS TO AVOID ATTACKS LIKE 26/11 *318. SHRIMATI RAJANI PATIL: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased to state the details of steps taken by Government to avoid attacks like 26/11 in the country by foreign elements, particularly keeping in view the threats being received from terrorist groups from foreign countries? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI HARIBHAI PARATHIBHAI CHAUDHARY) A Statement is laid on the Table of the House. ******* -2- STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO.*318 FOR 17.12.2014. Public Order and Police are State subjects. Thus, the primary responsibility to address these issues remains with the State Governments. However, the Central Government is of the firm belief that combating terrorism is a shared responsibility of the Central and the State Governments. In order to deal with the menace of extremism and terrorism, the Government of India has taken various measures which, inter-alia, include augmenting the strength of Central Armed Police Forces; establishment of NSG hubs at Chennai, Kolkata, Hyderabad and Mumbai; empowerment of DG, NSG to requisition aircraft for movement of NSG personnel in the event of any emergency; tighter immigration control; effective border management through round the clock surveillance & patrolling on the borders; establishment of observation posts, border fencing, flood lighting, deployment of modern and hi- tech surveillance equipment; upgradation of Intelligence setup; and coastal security by way of establishing marine police stations along the coastline. -

Border Security Force Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India

Border Security Force Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India RECRUITMENT OF MERITORIOUS SPORTSPERSONS TO THE POST OF CONSTABLE (GENERAL DUTY) UNDER SPORTS QUOTA 2020-21 IN BORDER SECURITY FORCE Application are invited from eligible Indian citizen (Male & Female) for filling up 269 vacancies for the Non- Gazetted & Non Ministerial post of Constable(General Duty) in Group “C” on temporary basis likely to be made permanent in Border Security Force against Sports quota as per table at Para 2(a). Application from candidate will be accepted through ON-LINE MODE only. No other mode for submission is allowed. ONLINE APPLICATION MODE WILL BE OPENED W.E.F.09/08/2021 AT 00:01 AM AND WILL BE CLOSED ON 22/09/2021 AT 11:59 PM. 2. Vacancies :- a) There are 269 vacancies in the following Sports/Games disciplines :- S/No. Name of Team Vac Nos of events/weight category 1 Boxing(Men) 49 Kg-2 52 Kg-1 56 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 10 64 Kg-1 69 Kg-1 75 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 91 + Kg-1 Boxing(Women) 10 48 Kg-1 51 Kg-1 54 Kg-1 57 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 64 Kg-1 69 Kg-1 71 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 81 + Kg-1 2 Judo(Men) 08 60 Kg-1 66 Kg-1 73 Kg-1 81 Kg-2 90 Kg-1 100 Kg-1 100 + Kg-1 Judo(Women) 08 48 Kg-1 52 Kg-1 57 Kg-1 63 Kg-1 70 Kg-1 78 Kg-1 78 + Kg-2 3 Swimming(Men) 12 Swimming Indvl Medley -1 Back stroke -1 Breast stroke -1 Butterfly Stroke -1 Free Style -1 Water polo Player-3 Golkeeper-1 Diving Spring/High board-3 Swimming(Women) 04 Water polo Player-3 Diving Spring/High board-1 4 Cross Country (Men) 02 10 KM-2 Cross Country(Women) 02 10 KM -2 5 Kabaddi (Men) 10 Raider-3 All-rounder-3 Left Corner-1 Right Corner1 Left Cover -1 Right Cover-1 6 Water Sports(Men) 10 Left-hand Canoeing-4 Right-hand Canoeing -2 Rowing -1 Kayaking -3 Water Sports(Women) 06 Canoeing -3 Kayaking -3 7 Wushu(Men) 11 48 Kg-1 52 Kg-1 56 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 65 Kg-1 70 Kg-1 75 Kg-1 80 Kg-1 85 Kg-1 90 Kg-1 90 + Kg-1 8 Gymnastics (Men) 08 All-rounder -2 Horizontal bar-2 Pommel-2 Rings-2 9 Hockey(Men) 08 Golkeeper1 Forward Attacker-2 Midfielder-3 Central Full Back-2 10 Weight Lifting(Men) 08 55 Kg-1 61 Kg-1 67 Kg-1 73 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 89 Kg-1 96 Kg-1 109 + Kg-1 Wt. -

Seventh Schedule of Indian Constitution - Article 246

Seventh Schedule of Indian Constitution - Article 246 The 7th Schedule of the Indian Constitution deals with the division of powers between the Union government and State governments. It is a part of 12 Schedules of Indian Constitution. The division of powers between Union and State is notified through three kinds of the list mentioned in the seventh schedule: 1. Union List – List I 2. State List – List II 3. Concurrent List – List III Union List, State List, Concurrent List – Introduction As mentioned earlier, Article 246 deals with the 7th Schedule of the Indian Constitution that mentions three lists named as Union List, State List and Concurrent List which specify the divisions of power between Union and States. The key features of Union List, State List & Concurrent List are mentioned in the tables below: 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution – Union List It originally had 97 subjects. Now, it has 100 subjects Centre has exclusive powers to makes laws on the subjects mentioned under the Union List of Indian Constitution The Union List signifies the strong centre as it has more subjects than state list It contains more important subjects than included in any of the other two lists All the issues/matters that are important for the nation and those requiring uniformity of legislation nationwide are included in the Union List The dominance of Union List over State List is secured by the Constitution of India as in any conflict between the two or overlapping, the Union List prevails Law made by the Parliament on a subject of the Union List can confer powers and impose duties on a state, or authorise the conferring of powers and imposition of duties by the Centre upon a state There are 15 subjects in the Union List on which Parliament has an exclusive power to levy taxes 88th Amendment added a new subject in the Union List called ‘taxes on services.’ Supreme Court’s jurisdiction and powers with respect to matters in the Union list can be enlarged by the Parliament 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution – State List It has 61 subjects. -

Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Stakeholderfor andAnalysis Plan Engagement Sund arban Joint ManagementarbanJoint Platform Document Information Title Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform Submitted to The World Bank Submitted by International Water Association (IWA) Contributors Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal, Sakib Mahmud Deliverable Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban description Joint Management Platform Version number Final Actual delivery date 05 April 2016 Dissemination level Members of the BISRCI Consortia Reference to be Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal and Sakib used for citation Mahmud. Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform (2016). International Water Association Cover picture Elderly woman pulling shrimp fry collecting nets in a river in Sundarban by AJM Zobaidur Rahman Contact Bushra Nishat, Programmes Manager South Asia, International Water Association. [email protected] Prepared for the project Bangladesh-India Sundarban Region Cooperation (BISRCI) supported by the World Bank under the South Asia Water Initiative: Sundarban Focus Area Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

In the Supreme Court of India Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction Criminal Appeal No

[REPORTABLE] IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 2231 OF 2009 Satyavir Singh Rathi ….Appellant Versus State thr. C.B.I. ….Respondent WITH CRIMINAL APPEAL NOs.2476/2009, 2477-2483/2009 and 2484/2009. J U D G M E N T HARJIT SINGH BEDI, J. This judgment will dispose of Criminal Appeal Nos.2231 of 2009, 2476 of 2009 and 2477-2484 of 2009. The facts have been taken from Criminal Appeal No. 2231 of 2009 (Satyavir Singh Rathi vs. State thr. C.B.I.). On the 31st March 1997 Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh PW-11 both hailing from Kurukshetra in the State of Haryana came to Delhi to meet Pradeep Goyal in his office situated near the Mother Dairy Booth in Patparganj, Delhi. They reached the office premises between 12.00 noon and 1.00 Crl. Appeal No.2231/2009 etc. 2 p.m. but found that Pradeep Goyal was not present and the office was locked. Jagjit Singh thereupon contacted Pradeep Goyal on his Mobile Phone and was told by the latter that he would be reaching the office within a short time. Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh, in the meanwhile, decided to have their lunch and after buying some ice-cream from the Mother Dairy Booth, waited for Pradeep Goyal’s arrival. Pradeep Goyal reached his office at about 1.30 p.m. but told Jagjit Singh and Tarunpreet Singh that as he had some work at the Branch of the Dena Bank in Connaught Place, they should accompany him to that place. -

Proposals for Constitutional Change in Myanmar from the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional Amendment International Idea Interim Analysis

PROPOSALS FOR CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN MYANMAR FROM THE JOINT PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT INTERNATIONAL IDEA INTERIM ANALYSIS 1. Background, Purpose and Scope of this Report: On 29 January Myanmar’s Parliament voted to establish a committee to review the constitution and receive proposals for amendments. On July 15 a report containing a catalogue of each of these proposals was circulated in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (Union Legislature). This International IDEA analysis contains an overview and initial assessment of the content of these proposals. From the outset, the Tatmadaw (as well as the Union Solidarity and Development Party - USDP) has objected to this process of constitutional review,i and unless that opposition changes it would mean that the constitutional review process will not be able to proceed much further. Passing a constitutional amendment requires a 75% supermajority in the Union Legislature, which gives the military an effective veto as they have 25% of the seats.1 Nevertheless, the report provides the first official public record of proposed amendments from different political parties, and with it a set of interesting insights into the areas of possible consensus and divergence in future constitutional reform. The importance of this record is amplified by the direct connection of many of the subjects proposed for amendment to the Panglong Peace Process agenda. Thus far, the analyses of this report available publicly have merely counted the number of proposals from each party, and sorted them according to which chapter of the constitution they pertain to. But simply counting proposals does nothing to reveal what changes are sought, and can be misleading – depending on its content, amending one significant article may bring about more actual change than amending fifty other articles. -

India's Police Complaints Authorities

India’s Police Complaints Authorities: A Broken System with Fundamental Flaws A Legal Analysis CHRI Briefing Paper September 2020 Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) is an independent, non-governmental, non- profit organisation headquartered in New Delhi, with offices in London, United Kingdom, and Accra, Ghana. Since 1987, it has worked for the practical realization of human rights through strategic advocacy and engagement as well as mobilization around these issues in Commonwealth countries. CHRI’s specialisation in the areas of Access to Justice (ATJ) and Access to Information (ATI) are widely known. The ATJ programme has focussed on Police and Prison Reforms, to reduce arbitrariness and ensure transparency while holding duty bearers to account. CHRI looks at policy interventions, including legal remedies, building civil society coalitions and engaging with stakeholders. The ATI looks at Right to Information (RTI) and Freedom of Information laws across geographies, provides specialised advice, sheds light on challenging issues, processes for widespread use of transparency laws and develops capacity. CHRI reviews pressures on freedom of expression and media rights while a focus on Small States seeks to bring civil society voices to bear on the UN Human Rights Council and the Commonwealth Secretariat. A growing area of work is SDG 8.7 where advocacy, research and mobilization is built on tackling Contemporary Forms of Slavery and human trafficking through the Commonwealth 8.7 Network. CHRI has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council and is accredited to the Commonwealth Secretariat. Recognised for its expertise by governments, oversight bodies and civil society, it is registered as a society in India, a trust in Ghana, and a public charity in the United Kingdom. -

International Terrorism -- Sixth Committee

Please check against delivery STATEMENT BY SHRI ARON JAITLEY HONOURABLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT AND MEMBER OF THE INDIAN DELEGATION ON AGENDA ITEM 110 "MEASURES TO ELIMINATE INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM" ATTHE SIXTH COMMITTEE OF THE 68TH SESSION OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY New York 8 October 2013 Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations 235 East 43rd Street, New York, NY 10017 • Tel: (212) 490-9660 • Fax: (212) 490-9656 E-Mail: [email protected] • [email protected] Mr. Chairman, At the outset, I congratulate you for your election as the Chairperson of the Sixth Committee. I also congratulate other members of the Bureau on their election. I assure you of full cooperation and support of the Indian delegation during the proceedings of the Committee. I would also like to thank the Secretary-General for his report A/68/180 dated 23 July 2013 entitled "Measures to eliminate international terrorism". Mr. Chairman, The international community is continuously facing a grave challenge from terrorism. It is a scourge that undermines peace, democracy and freedom. It endangers the foundation of democratic societies. Terrorists are waging an asymmetric warfare against the international community, and are a major most threat to the international peace and security. India holds the firm view that no cause whatsoever or grievance could justify terrorism. India condemns terrorism in all its forms and manifestations, including those in which States are directly or indirectly involved, including the State-sponsored cross-border terrorism, and reiterates the call for the adoption of a holistic approach that ensures zero-tolerance towards terrorism. Mr.