Transatlantic Multilingualism in Latin American and Maghreb Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Librib 494218.Pdf

OTTOBRE 1997 N. 9 ANNO XIV LIRE 9.500 MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - SPED. IN ABB. POST. COMMA 20/b ART. 2, LEGGE 662/96 - ROMA - ISSN 0393 - 3903 Ottobre 1997 In questo numero Giorgio Calcagno, Primo Levi per l'Aned IL LIBRO DEL MESE 28 Carmine Donzelli, De Historia di Hobsbawm 6 Atlante del romanzo europeo 30 Federica Matteoli, La vita di Le Goff di Franco Moretti 31 Norberto Bobbio, Sull'intellettuale di Garin recensito da Mariolina Bertini e Daniele Del Giudice 32 Schede INTERVISTA VIAGGIATORI 33 Giorgio Baratta, Edoardo Sanguineti su Gramsci 8 Piero Boitani, Riletture di Ulisse POLITICA Paola Carmagnani, Viaggio in Oriente di Nerval 9 Franco Marenco, Viaggi in Italia 34 Francesco Ciafaloni, L'autobiografia di Pio Galli 10 Giovanni Cacciavillani, Le Madri di Nerval 36 Cent'anni fa il Settantasette, schede LETTERATURE GIORNALISMO 11 Carlo Lauro, Le Opere di Flaubert 37 Claudio Gorlier, Càndito inviato di guerra Sandro Volpe, Gli anni di Jules e Jim Alberto Papuzzi, Lapidarium di Kapuscinski 12 Marco Buttino, L'autobiografia di Markus Wolf Angela Massenzio, Il mostro di Crane FILOSOFIA 13 Poeti colombiani, fotografe messicane e filosofi spagnoli, schede 38 Roberto Deidier, L'estetica del Romanticismo di Rella Gianni Carchia, Il concilio di Nicea NARRATORI ITALIANI ANTROPOLOGIA 14 Silvio Perrella, Tempo perso di Arpaia 39 Mario Corona, L'immagine dell'uomo di Mosse Cosma Siani, I giubilanti di Cassieri Lidia De Federicis, Percorsi della narrativa italiana: Napoletani SCIENZE 15 Santina Mobiglia, Prigioniere della Torre di Peyrot Biancamaria -

2013-14 Hamilton College Catalogue

2013-14 Hamilton College Catalogue Courses of Instruction Departments and Programs Page 1 of 207 Updated Jul. 31, 2013 Departments and Programs Africana Studies American Studies Anthropology Art Art History Asian Studies Biochemistry/Molecular Biology Biology Chemical Physics Chemistry Cinema and New Media Studies Classics College Courses and Seminars Communication Comparative Literature Computer Science Critical Languages Dance and Movement Studies Digital Arts East Asian Languages and Literatures Economics Education Studies English and Creative Writing English for Speakers of Other Languages Environmental Studies Foreign Languages French Geoarchaeology Geosciences German Studies Government Hispanic Studies History Jurisprudence, Law and Justice Studies Latin American Studies Mathematics Medieval and Renaissance Studies Middle East and Islamic World Studies Music Neuroscience Oral Communication Philosophy Physical Education Physics Psychology Public Policy Religious Studies Russian Studies Sociology Theatre Women's Studies Writing Courses of Instruction Page 2 of 207 Updated Jul. 31, 2013 Courses of Instruction For each course, the numbering indicates its general level and the term in which it is offered. Courses numbered in the 100s, and some in the 200s, are introductory in material and/or approach. Generally courses numbered in the 200s and 300s are intermediate and advanced in approach. Courses numbered in the 400s and 500s are most advanced. Although courses are normally limited to 40 students, some courses have lower enrollment limits due to space constraints (e.g., in laboratories or studios) or to specific pedagogical needs (e.g., special projects, small-group discussions, additional writing assignments). For example, writing-intensive courses are normally limited to 20 students, and seminars are normally limited to 12. -

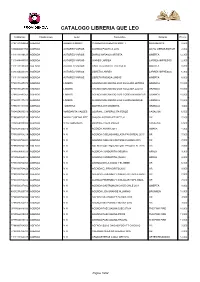

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

NEMLA 2014.Pdf

Northeast Modern Language Association 45th Annual Convention April 3-6, 2014 HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA Local Host: Susquehanna University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo CONVENTION STAFF Executive Director Fellows Elizabeth Abele SUNY Nassau Community College Chair and Media Assistant Associate Executive Director Caroline Burke Carine Mardorossian Stony Brook University, SUNY University at Buffalo Convention Program Assistant Executive Associate Seth Cosimini Brandi So University at Buffalo Stony Brook University, SUNY Exhibitor Assistant Administrative Assistant Jesse Miller Renata Towne University at Buffalo Chair Coordinator Fellowship and Awards Assistant Kristin LeVeness Veronica Wong SUNY Nassau Community College University at Buffalo Marketing Coordinator NeMLA Italian Studies Fellow Derek McGrath Anna Strowe Stony Brook University, SUNY University of Massachusetts Amherst Local Liaisons Amanda Chase Marketing Assistant Susquehanna University Alison Hedley Sarah-Jane Abate Ryerson University Susquehanna University Professional Development Assistant Convention Associates Indigo Eriksen Rachel Spear Blue Ridge Community College The University of Southern Mississippi Johanna Rossi Special Events Assistant Wagner Pennsylvania State University Francisco Delgado Grace Wetzel Stony Brook University, SUNY St. Joseph’s University Webmaster Travel Awards Assistant Michael Cadwallader Min Young Kim University at Buffalo Web Assistant Workshop Assistant Solon Morse Maria Grewe University of Buffalo Columbia University NeMLA Program -

Guia De Numã©Ros

Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica Number 49 Foro Escritura y Psicoanálisis Article 100 1999 Guia de Numéros Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti Citas recomendadas (Primavera-Otoño 1999) "Guia de Numéros," Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica: No. 49, Article 100. Available at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti/vol1/iss49/100 This Otras Obras is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTI: NUMEROS PUBLICADOS Y LISTA DE PRECIOS PARA SUSCRIPTORES NO. 1 $6.00 Robert G. Mead Jr., Presentación de Inti; ESTUDIOS: Carlos Alberto Pérez, “Canciones y romances (Edad Media-Siglo XVIII)”; Robert G. Mead Jr., “Imágenes y realidades interamericanas”; Nelson R . Orringer, “La espada y el arado: una refutación lírica de Juan Ramón por Blas de Otero”; Luis Alberto Sánchez, “La terca realidad”; CREACIÓN: Saúl Yurkievich, Josefina Romo-Arregui. NO. 2 $6.00 ESTUDIOS: Estelle Irizarri, “El Inquisidor de Ayala y el de Dostoyevsky”; Nelson R. Orringer, “El Góngora rebelde del Don Julián de Goytisolo”; Ronald J. Quirk, “El problema del habla regional en Los Pasos de Ulloa "; Gail Solano, "Las metáforas fisiológicas en Tiempo de silencio de Luis Martín Santos”; CREACIÓN: Flor María Blanco, Pedro Lastra, Antonio Silva Domínguez, Saúl Yurkievich; RESEÑAS: Helen Vendler, "El arco y la lira de Octavio Paz; Robert G. Mead Jr., “El intelectual hispanoamericano y su suerte en Chile”; Francisco Ayala, “Las cartas sobre la mesa”. NO. -

Lecturas Para El Verano Por Autor

LECTURAS PARA EL VERANO POR AUTOR AUTOR TÍTULO SIGNATURA Amadís de Gaula / Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo anotación de Juan Bautista Avalle-Arce A 510/3/25 Cuando se abrió la puerta : cuentos de la nueva mujer (1882-1914) / selección y presentación, Marta Salís traducción, Claudia Conde ... [et al.] A 512/5/26 La dulce mentira de la ficción : ensayos sobre la literatura española actual / Hans Felten, Agustin Valcárcel (eds), en colaboración con David Nelting A 509/7/57 La tragedia de Agamenón, rey de Micenas / Bartolomé Segura Ramos ... [et al.] A 511/6/44 La tragedia de Agamenón, rey de Micenas / Bartolomé Segura Ramos ... [et al.] A 511/6/43 Leer a Hemingway A 509/5/21 Abdolah, Kader El reflejo de las palabras / KaderAbdolah [traducción, Diego Puls Kuipers] A 509/5/31 Agus, Milena Mal de piedras / Milena Agus traducción del italiano de Celia Filipetto. A 512/5/02 Alí, Tariq A la sombra del Granado / Tariq Alí A 508/7/17 Allen, Woody, 1935- Pura anarquía / Woody Allen traducción de Carlos Milla Soler A 508/6/58 Allende, Isabel, 1942- La suma de los días / Isabel Allende A 508/1/14 1 Amat, Núria, 1950- Viajar es muy dificil / Nuria Amat i Noguera prólogo de Ana María Moix A 512/6/24 Amis, Martin La casa de los encuentros / Martin Amis traducción de Jesús Zulaika A 509/6/44 Anasagasti Valderrama, Antonio Arrítmico Amor / Antonio Anasagasti Valderrama A 510/6/41 Antunes, António Lobo Acerca de los pájaros / António Lobo Antunes traducción de Mario Merlino A 509/5/17 El señor Skeffington / Elizabeth von Arnim traducción de Sílvia Pons Arnim, -

Anuario Sobre El Libro Infantil Y Juvenil 2009

122335_001-006_AnuarioInfantilJuvenil_09 27/2/09 11:27 PÆgina 1 gifrs grterstis FUNDACIÓN seromri e 122335_001-006_AnuarioInfantilJuvenil_09 27/2/09 11:27 PÆgina 2 www.grupo-sm.com/anuario.html © Ediciones SM, 2009 Impresores, 2 Urbanización Prado del Espino 28660 Boadilla del Monte (Madrid) www.grupo-sm.com ATENCIÓN AL CLIENTE Tel.: 902 12 13 23 Fax: 902 24 12 22 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-84-675-3466-5 Depósito legal: Impreso en España / Printed in Spain Gohegraf Industrias Gráficas, SL - 28977 Casarrubuelos (Madrid) Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra solo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Diríjase a CEDRO (Centro Español de Derechos Reprográficos, www.cedro.org) si necesita fotocopiar o escanear algún fragmento de esta obra. 122335_001-006_AnuarioInfantilJuvenil_09 27/2/09 11:27 PÆgina 3 ÍNDICE Presentación 5 1. Cifras y estadísticas: 7 LA LIJ en 2009 Departamento de Investigación de SM 2. Características y tendencias: 27 AÑO DE FANTASY, EFEMÉRIDES Y REALISMO Victoria Fernández 3. Actividad editorial en catalán: 37 TIEMPO DE BONANZA Te re s a M a ñ à Te r r è 4. Actividad editorial en gallego: 45 PRESENCIA Y TRASCENDENCIA Xosé Antonio Neira Cruz 5. Actividad editorial en euskera: 53 BUENA COSECHA Xabier Etxaniz Erle 6. La vida social de la LIJ: 61 DE CLÁSICOS Y ALLEGADOS, DE HONESTIDAD Y OPORTUNISMO... Sara Moreno Valcárcel 7. Actividad editorial en Brasil: 113 VIGOR Y DIVERSIDAD João Luís Ceccantini 8. Actividad editorial en Chile: 135 ANIMAR A LEER: ¿SALTOS DE ISLOTE EN ISLOTE? María José González C. -

SUMARIO JOSÉ MARÍA MARTÍNEZ, El Público Femenino Del Modernismo

S U M A R I O I. DOSSIERS LITERATURA Y GÉNERO JOSÉ MARÍA MARTÍNEZ, El público femenino del modernismo: de la lectora figurada a la lectora histórica en las prosas de Gutiérrez Nájera ... ... ... ... ... 15 JOSSIANNA ARROYO, Exilio y tránsitos entre la Norzagaray y Christopher Street: acercamientos a una poética del deseo homosexual en Manuel Ramos Otero 31 DENISE GALARZA SEPÚLVEDA, “Las mujeres son las que comúnmente mandan el mundo”: la feminización de lo político en El carnero ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 55 JORGE LUIS CAMACHO, Los límites de la transgresión: la virilización de la mujer y la feminización del poeta en José Martí ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 69 MARISELLE MELÉNDEZ, Inconstancia en la mujer: espacio y cuerpo femenino en el Mercurio peruano, 1791-94 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 79 LITERATURA ARGENTINA LELIA AREA, Geografías imaginarias: el Facundo y la Campaña en el Ejército Grande de Domingo Faustino Sarmiento ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 91 PATRICIO RIZZO-VAST, Paisaje e ideología en Campo nuestro de Oliverio Girondo ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 105 MARGARITA ROJAS y FLORA OVARES, La tenaz memoria de esos hechos; “El perjurio de la nieve” de Adolfo Bioy Casares ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 121 LAURA DEMARÍA, Rodolfo Walsh, Ricardo Piglia, la tranquera de Macedonio y el difícil oficio de escribir ... ... ... ... ... ... .. -

Albo D'oro Dei Vincitori Del Mondello

Albo d’Oro dei vincitori del Premio Letterario Internazionale Mondello 1975 BARTOLO CATTAFI, letteratura UGO DELL’ARA, teatro DENIS MCSMITH, Premio speciale della Giuria 1976 ACHILLE CAMPANILE, letteratura ANTONINO ZICHICHI, scienze fisiche DOMENICO SCAGLIONE, scienze finanziarie FELICE CHILANTI, giornalismo FRANCESCO ROSI, cinema GIAMPIERO ORSELLO, informazione PAOLA BORBONI, teatro 1977 GÜNTER GRASS, letteratura SERGIO AMIDEI, SHELLEY WINTERS, cinema ROMOLO VALLI, ROBERTO DE SIMONE, teatro GIULIANA BERLINGUER, EMILIO ROSSI, televisione PIETRO RIZZUTO, lavoro STEFANO D’ARRIGO, Premio speciale della Giuria 1978 MILAN KUNDERA, Il valzer degli addii (Bompiani), narrativa straniera GHIANNIS RITSOS, Tre poemetti (Guanda), poesia straniera CARMELO SAMONÀ, Fratelli (Einaudi), opera prima narrativa GIOVANNI GIUGA, Poesie da Smerdjakov (Lacaita), opera prima poetica ANTONELLO AGLIOTTI, FRANCO CHIARENZA, MUZI LOFFREDO, GIOVANNI POGGIALI, GIULIANO VASILICÒ, teatro JURIJ TRIFONOV, Premio speciale della Giuria 1979 N. S. MOMADAY, Casa fatta di alba (Guanda), narrativa straniera JOSIF BRODSKIJ, Fermata nel deserto (Mondadori), poesia straniera FAUSTA GARAVINI, Gli occhi dei pavoni (Vallecchi), PIERA OPPEZZO, Minuto per minuto (La Tartaruga), opera prima narrativa GILBERTO SACERDOTI, Fabbrica minima e minore (Pratiche), opera prima poetica LEO DE BERARDINIS, PERLA PERAGALLO, teatro JAROSLAW IWASZKIEVICZ, Premio speciale della Giuria 1980 JUAN CARLOS ONETTI, Gli addii (Editori Riuniti), narrativa straniera JUAN GELMAN, Gotan (Guanda), poesia straniera -

LOS LIBROS DE 2014 Estos Son Los Títulos Elegidos Por Los Críticos Y

LOS LIBROS DE 2014 Estos son los títulos elegidos por los críticos y periodistas de EL PAÍS. Cada uno de ellos otorgó 10 puntos al primero de su lista, 9 al segundo y así sucesivamente JESÚS AGUADO El capital en el siglo XXI. Thomas Piketty. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Manuel de filosofía portátil. Juan Arnau. Atalanta La vida en verso. Biografía poética de Friedrich Hölderlin. Helena Cortés. Hiperión Hojas de hierba. Walt Whitman. Galaxia Gutenberg /Círculo de Lectores Días de mi vida. (Vida. Volumen I). Juan Ramón Jiménez. Pre-Textos Musketaquid. Henry David Thoreau. Errata Naturae No tan incendiario. Marta Sanz. Periférica Mi aliento se llama ahora (y otros poemas). Rose Ausländer. Igitur El caso maiakovski. Laura Pérez Vernetti. Lúces de Galibo El cerebro de Andrew. E. L. Doctorow. Miscelánea GUILLERMO ALTARES Sonámbulos. Christopher Clark. Galaxia Gutenberg Los extraños. Vicente Valero. Periférica Puta guerra. Jacques Tardi. Norma Juego de espejos. Andrea Camilleri. Salamandra Vestido de novia. Pierre LeMaitre. Alfaguara Guerreros y traidores. Jorge Martínez Reverte. Galaxia Gutenberg Delizia. John Dickie. Debate El último tramo. De las puertas de hierro al Monte Athos. Patrick Leigh Fermor. RBA Un reguero de pólvora. Rebecca West. Reino de Redonda Augusto. Adrian Goldsworthy. La Esfera de los Libros JACINTO ANTÓN Regreso a la isla del tesoro. Andrew Motion. Tusquets Nos vemos allá arriba. Pierre Lemaitre. Salamandra El último tramo. Patrick Leigh Fermor. RBA El leopardo. Jo Nesbo. Random House Los cañones del atardecer. Rick Atkinson. Crítica Sonámbulos. Christopher Clark. Galaxia Gutemberg. Sirenas. Carlos García Gual. Turner La guerra como aventura. La Legión Cóndor en la Guerra Civil española 1936-39. -

Los Adioses De Juan Carlos Onetti Por Maria Angelica

LOS ADIOSES DE JUAN CARLOS ONETTI UN MODELO DE ESCRITURA HERMeTICA-ABIERTA POR MARIA ANGELICA PETIT OMAR PREGO GADEA Universidad de la Repiblica, Montevideo La novela cortaLos adiosesconstituye, en mas de un sentido, una obra dclave dentro de la summa narrativa del escritor Juan Carlos Onetti. La nouvelle fue publicada en 1954 por la editorial Sur, de Buenos Aires.' Editada cuatro aios despues de La vida breve (es decir, luego de la fundaci6n de Santa Marfa por Juan Maria Brausen) y siete antes de la aparici6n de El astillero-considerada por muchos criticos como la novela mayor de Onetti- Los adioses suscit6 de inmediato un perplejo asedio de la critica y un minucioso resentimiento entre muchos de sus lectores. A primera vista, ese desencuentro entraba en el orden natural de las cosas, si se considera que la obra de Onetti es hermetica y que el escritor no este dispuesto a hacer concesiones de clase alguna. Onetti parece custodiar los senderos secretos que conducen a las fuentes de su creaci6n con burl6n escepticismo, si no con sarcasmo. A titulo ilustrativo puede mencionarse el persistente desencuentro entre los exdgetas de Para esta noche y las circunstancias que rodearon su creaci6n. O el desconcierto provocado por la aparici6n de La vida breve y alguna que otra diatriba. 2 La diferencia radical entre aquellos desenfoques, en iltima instancia adjetivos y no sustantivos, y el persistente malentendido que rode6 (y sigue rodeando) a Los adioses, consiste en que aquf se trata de una incomprensi6n basica de lo que esta novela significa, no s6lo en la obra de Onetti, sino en el terreno mucho mas vasto de la literatura latinoamericana. -

Relaciones Y Hechos De Juan Gelman: “Disparos De La Belleza Incesante”

Revista Iberoamericana. Vol. LXVII, Núms. 194-195, Enero-Junio 2001, 145-159 RELACIONES Y HECHOS DE JUAN GELMAN: “DISPAROS DE LA BELLEZA INCESANTE” POR VÍCTOR RODRÍGUEZ NÚÑEZ The University of Texas at Austin I En la primera mitad de la década de 1970, mientras Octavio Paz proclamaba el fin, en el proceso de las letras hispanoamericanas, de “la tradición que se niega a sí misma para continuarse, la tradición de ruptura” inaugurada por el romanticismo y cerrada por la vanguardia (145), y por consiguiente el ocaso “tanto de la noción de futuro como de cambio” (205), Juan Gelman daba a la luz sus Relaciones.1 La conexión entre las ideas de Paz y el quehacer de Gelman, que estaría justificada simplemente por ser producciones literarias contemporáneas de Hispanoamérica, se hace explícita cuando el hablante lírico del segundo interroga al primero —y a otros miembros de la llamada generación posvanguardista— en una de las piezas claves de este libro, escrito entre 1971 y 1973.2 1 Juan Gelman nació en 1930 en Buenos Aires, como parte de una familia de inmigrantes ucranianos. Creció como cualquier porteño, entre balonazos y milongas, en el barrio de Villa Crespo. Fue iniciado en la lectura por su hermano Boris, quien le recitaba en ruso versos de Pushkin. De él recibió obras de Dostoiesky, Tolstoy, Víctor Hugo y otros clásicos. A los once años publicó su primer poema en la revista Rojo y negro, y en la década de 1950 formó parte del grupo El Pan Duro. Fue en uno de los recitales de este grupo donde lo descubrió Raúl González Tuñón, quien vio en los versos del joven “un lirismo rico y vivaz y un contenido principalmente social [...] que no elude el lujo de la fantasía”.