Draft – Not for Circulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Videos Bearbeiten Im Überblick: Sieben Aktuelle VIDEOSCHNITT Werkzeuge Für Den Videoschnitt

Miller: Texttool-Allrounder Wego: Schicke Wetter-COMMUNITY-EDITIONManjaro i3: Arch-Derivat mit bereitet CSVs optimal auf S. 54 App für die Konsole S. 44 Tiling-Window-Manager S. 48 Frei kopieren und beliebig weiter verteilen ! 03.2016 03.2016 Guter Schnitt für Bild und Ton, eindrucksvolle Effekte, perfektes Mastering VIDEOSCHNITT Videos bearbeiten Im Überblick: Sieben aktuelle VIDEOSCHNITT Werkzeuge für den Videoschnitt unter Linux im Direktvergleich S. 10 • Veracrypt • Wego • Wego • Veracrypt • Pitivi & OpenShot: Einfach wie noch nie – die neue Generation der Videoschnitt-Werkzeuge S. 20 Lightworks: So kitzeln Sie optimale Ergebnisse aus der kostenlosen Free-Version heraus S. 26 Verschlüsselte Daten sicher verstecken S. 64 Glaubhafte Abstreitbarkeit: Wie Sie mit dem Truecrypt-Nachfolger • SQLiteStudio Stellarium Synology RT1900ac Veracrypt wichtige Daten unauffindbar in Hidden Volumes verbergen Stellarium erweitern S. 32 Workshop SQLiteStudio S. 78 Eigene Objekte und Landschaften Die komfortable Datenbankoberfläche ins virtuelle Planetarium einbinden für Alltagsprogramme auf dem Desktop Top-Distris • Anydesk • Miller PyChess • auf zwei Heft-DVDs ANYDESK • MILLER • PYCHESS • STELLARIUM • VERACRYPT • WEGO • • WEGO • VERACRYPT • STELLARIUM • PYCHESS • MILLER • ANYDESK EUR 8,50 EUR 9,35 sfr 17,00 EUR 10,85 EUR 11,05 EUR 11,05 2 DVD-10 03 www.linux-user.de Deutschland Österreich Schweiz Benelux Spanien Italien 4 196067 008502 03 Editorial Old and busted? Jörg Luther Chefredakteur Sehr geehrte Leserinnen und Leser, viele kleinere, innovative Distributionen seit einem Jahrzehnt kommen Desktop- Immer öfter stellen wir uns aber die haben damit erst gar nicht angefangen und Notebook-Systeme nur noch mit Frage, ob es wirklich noch Sinn ergibt, oder sparen es sich schon lange. Open- 64-Bit-CPUs, sodass sich die Zahl der moderne Distributionen überhaupt Suse verzichtet seit Leap 42.1 darauf; das 32-Bit-Systeme in freier Wildbahn lang- noch als 32-Bit-Images beizulegen. -

Download the Booklet of Chessbase Magazine #199

THE Magazine for Professional Chess JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2021 | NO. 199 | 19,95 Euro S R V ON U I O D H E O 4 R N U A N DVD H N I T NG RE TIME: MO 17 years old, second place at the Altibox Norway Chess: Alireza Firouzja is already among the Top 20 TOP GRANDmasTERS ANNOTATE: ALL IN ONE: SEMI-TaRRasCH Duda, Edouard, Firouzja, Igor Stohl condenses a Giri, Nielsen, et al. trendy opening AVRO TOURNAMENT 1938 – LONDON SYSTEM – no reST FOR THE Bf4 CLash OF THE GENERATIONS Alexey Kuzmin hits with the Retrospective + 18 newly annotated active 5...Nh5!? Keres games THE MODERN BENONI UNDER FIRE! Patrick Zelbel presents a pointed repertoire with 6.Nf3/7.Bg5 THE MAGAZINE FOR PROFESSIONAL CHESS JANU 17 years old, secondARY / placeFEB at the RU Altibox Norway Chess: AlirezaAR FirouzjaY 2021 is already among the Top 20 NO . 199 1 2 0 2 G R U B M A H , H B M G E S DVD with first class training material for A B S S E club players and professionals! H C © EDITORIAL The new chess stars: Alireza Firouzja and Moscow in order to measure herself against Beth Harmon the world champion in a tournament. She is accompanied by a US official who warns Now the world and also the world of chess her about the Soviets and advises her not to has been hit by the long-feared “second speak with anyone. And what happens? She wave” of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many is welcomed with enthusiasm by the popu- tournaments have been cancelled. -

A New Look at the Tayler by David Kane

A New Look at the Tayler by David kane I: Introduction The Tayler Variation (aka the Tayler Opening) is a line that has been unjustly neglected, in my view. The line is of surprisingly recent vintage though it is often confused with the Inverted Hungarian (or Inverted Hanham Defense), a line which shares the same opening moves: 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Be2: The Inverted Hungarian is an old opening, dating back to the 1860ʼs, at least. Tartakower played it a few times in the 1920ʼs with mixed results, using the continuation, 3...Nf6 4. d3: a rather unenterprising setup for White. In 1981 British player, John Tayler (see biographical note), published an article in the British publication Chess (vol. 46) on a line he had developed stemming from the sharp 4. d4!?. This is a move which apparently no one had thought to play before, and one that transforms the sedate Inverted Hungarian into something else altogether. Technically, it is really the Tayler Variation to the Inverted Hungarian Defense rather than the Tayler Opening, though through usage, the terms are interchangeable for all practical purposes. As has been so often the case when it comes to unorthodox lines, I first heard of this opening via Mike Basman when he published a cassette on it back in the early 80ʼs (still available through audiochess.com). Tayler 2 The line stirred some interest at the time but gradually seems to have been forgotten. The final nail in the coffin was probably some light analysis published by Eric Schiller in Gambit Chess Openings (and elsewhere) where he dismisses the line primarily due to his loss in the game Schiller-Martinovsky, Chicago 1986. -

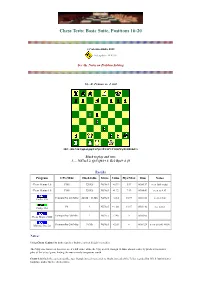

Chess Tests: Basic Suite, Positions 16-20

Chess Tests: Basic Suite, Positions 16-20 (c) Valentin Albillo, 2020 Last update: 14/01/98 See the Notes on Problem Solving 16.- Z. Franco vs. J. Gil FEN: rbb1N1k1/pp1n1ppp/8/2Pp4/3P4/4P3/P1Q2PPq/R1BR1K2/ b Black to play and win: 1. ... Nd7xc5 2. Qc5 Qh1+ 3. Ke2 Bg4+ 4. f3 Results Program CPU/Mhz Hash table Move Value Plys/Max Time Notes Chess Genius 1.0 P100 320 Kb Nd7xc5 +0.39 5/17 00:00:17 sees little value Chess Genius 1.0 P100 320 Kb Nd7xc5 +1.72 7/19 00:04:49 sees to 4. f3 Pentium Pro 200 MHz 24 Mb + 16 Mb Nd7xc5 +2.14 10/19 00:01:20 seen at 14s Crafty 12.6 P6 ? Nd7xc5 +1.181 11/17 00:01:46 see notes Crafty 13.3 Pentium Pro 200 Mhz ? Nd7xc5 +2.46 9 00:03:05 Chess Master 5500 Pentium Pro 200 Mhz 10 Mb Nd7xc5 +2.65 6 00:01:24 seen at 0:00, +0.00 MChess Pro 5.0 Notes: Using Chess Genius 1.0, both searches find the correct Knight's sacrifice. The 5-ply one, however, does not see it's full value, while the 7-ply search, though 16 times slower, correctly predicts the next 6 plies of the actual game, finding the move nearly two pawns worth. Crafty 12.6 finds the correct sacrifice too, though it needs to search to 10 ply, instead of the 7 plies required by CG1.0, but its better hardware makes for the shortest time. -

The SSDF Chess Engine Rating List, 2019-02

The SSDF Chess Engine Rating List, 2019-02 Article Accepted Version The SSDF report Sandin, L. and Haworth, G. (2019) The SSDF Chess Engine Rating List, 2019-02. ICGA Journal, 41 (2). 113. ISSN 1389- 6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190107 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/82675/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190085 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190107 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online THE SSDF RATING LIST 2019-02-28 148673 games played by 377 computers Rating + - Games Won Oppo ------ --- --- ----- --- ---- 1 Stockfish 9 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3494 32 -30 642 74% 3308 2 Komodo 12.3 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3456 30 -28 640 68% 3321 3 Stockfish 9 x64 Q6600 2.4 GHz 3446 50 -48 200 57% 3396 4 Stockfish 8 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3432 26 -24 1059 77% 3217 5 Stockfish 8 x64 Q6600 2.4 GHz 3418 38 -35 440 72% 3251 6 Komodo 11.01 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3397 23 -22 1134 72% 3229 7 Deep Shredder 13 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3360 25 -24 830 66% 3246 8 Booot 6.3.1 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3352 29 -29 560 54% 3319 9 Komodo 9.1 -

Chessbase.Com - Chess News - Grandmasters and Global Growth

ChessBase.com - Chess News - Grandmasters and Global Growth Grandmasters and Global Growth 07.01.2010 Professor Kenneth Rogoff is a strong chess grandmaster, who also happens to be one of the world's leading economists. In a Project Syndicate article that appeared this week Ken sees the new decade as one in which "artificial intelligence hits escape velocity," with an economic impact on par with the emergence of India and China. He uses computer chess to illustrated the point. Grandmasters and Global Growth By Kenneth Rogoff As the global economy limps out of the last decade and enters a new one in 2010, what will be the next big driver of global growth? Here’s betting that the “teens” is a decade in which artificial intelligence hits escape velocity, and starts to have an economic impact on par with the emergence of India and China. Admittedly, my perspective is heavily colored by events in the world of chess, a game I once played at a professional level and still follow from a distance. Though special, computer chess nevertheless offers both a window into silicon evolution and a barometer of how people might adapt to it. A little bit of history might help. In 1996 and 1997, World Chess Champion Gary Kasparov played a pair of matches against an IBM computer named “Deep Blue.” At the time, Kasparov dominated world chess, in the same way that Tiger Woods – at least until recently – has dominated golf. In the 1996 match, Deep Blue stunned the champion by beating him in the first game. -

March 2020 Uschess.Org the United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer

March 2020 USChess.org The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com ƩĂĐŬŝŶŐǁŝƚŚŐϮͲŐϰ The 100 Endgames You Must Know Workbook The Modern Way to Get the Upper Hand in Chess WƌĂĐƟĐĂůŶĚŐĂŵĞƐdžĞƌĐŝƐĞƐĨŽƌǀĞƌLJŚĞƐƐWůĂLJĞƌ Dmitry Kryavkin 288 pages - $24.95 Jesus de la Villa 288 pages - $24.95 dŚĞƉĂǁŶƚŚƌƵƐƚŐϮͲŐϰŝƐĂƉĞƌĨĞĐƚǁĂLJƚŽĐŽŶĨƵƐĞLJŽƵƌ ͞/ůŽǀĞƚŚŝƐŬ͊/ŶŽƌĚĞƌƚŽŵĂƐƚĞƌĞŶĚŐĂŵĞƉƌŝŶĐŝƉůĞƐLJŽƵ ŽƉƉŽŶĞŶƚƐĂŶĚĚŝƐƌƵƉƚƚŚĞŝƌƉŽƐŝƟŽŶ͘tŝƚŚůŽƚƐŽĨŝŶƐƚƌƵĐƟǀĞ ǁŝůůŶĞĞĚƚŽƉƌĂĐƟĐĞƚŚĞŵ͘͟ʹNM Han Schut, Chess.com ĞdžĂŵƉůĞƐ'D<ƌLJĂŬǀŝŶƐŚŽǁƐŚŽǁŝƚĐĂŶďĞƵƐĞĚƚŽĚĞĨĞĂƚ ͞dŚĞƉĞƌĨĞĐƚƐƵƉƉůĞŵĞŶƚƚŽĞůĂsŝůůĂ͛ƐŵĂŶƵĂů͘dŽŐĂŝŶ ůĂĐŬŝŶƚŚĞƵƚĐŚ͕ƚŚĞYƵĞĞŶ͛Ɛ'Ăŵďŝƚ͕ƚŚĞEŝŵnjŽͲ/ŶĚŝĂŶ͕ ƐƵĸĐŝĞŶƚŬŶŽǁůĞĚŐĞŽĨƚŚĞŽƌĞƟĐĂůĞŶĚŐĂŵĞƐLJŽƵƌĞĂůůLJŽŶůLJ ƚŚĞ<ŝŶŐ͛Ɛ/ŶĚŝĂŶ͕ƚŚĞ^ůĂǀĂŶĚƚŚĞŶŐůŝƐŚKƉĞŶŝŶŐ͘>ĞĂƌŶ ŶĞĞĚƚǁŽďŽŽŬƐ͘͟ʹIM Herman Grooten, Schaaksite NEW! ƚŚĞƚLJƉŝĐĂůǁĂLJƐƚŽŐĂŝŶƚĞŵƉŝ͕ŬĞĞƉƚŚĞŵŽŵĞŶƚƵŵĂŶĚ ŵĂdžŝŵŝnjĞLJŽƵƌŽƉƉŽŶĞŶƚ͛ƐƉƌŽďůĞŵƐ͘ Strategic Chess Exercises Keep It Simple 1.d4 Find the Right Way to Outplay Your Opponent ^ŽůŝĚĂŶĚ^ƚƌĂŝŐŚƞŽƌǁĂƌĚŚĞƐƐKƉĞŶŝŶŐZĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞĨŽƌtŚŝƚĞ Emmanuel Bricard 224 pages - $24.95 Christof Sielecki 432 pages - $29.95 &ŝŶĂůůLJĂŶĞdžĞƌĐŝƐĞƐŬƚŚĂƚŝƐŶŽƚĂďŽƵƚƚĂĐƟĐƐ͊ ^ŝĞůĞĐŬŝ͛ƐƌĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞǁŝƚŚϭ͘ĚϰŵĂLJďĞĞǀĞŶĞĂƐŝĞƌƚŽ ͞ƌŝĐĂƌĚŝƐĐůĞĂƌůLJĂǀĞƌLJŐŝŌĞĚƚƌĂŝŶĞƌ͘,ĞƐĞůĞĐƚĞĚĂƐƵƉĞƌď ŵĂƐƚĞƌƚŚĂŶŚŝƐϭ͘ĞϰƌĞĐŽŵŵĞŶĚĂƟŽŶƐ͕ďĞĐĂƵƐĞŝƚŝƐƐƵĐŚĂ ƌĂŶŐĞŽĨƉŽƐŝƟŽŶƐĂŶĚĞdžƉůĂŝŶƐƚŚĞƐŽůƵƟŽŶƐĞdžƚƌĞŵĞůLJ ĐŽŚĞƌĞŶƚƐLJƐƚĞŵ͗ƚŚĞŵĂŝŶĐŽŶĐĞƉƚŝƐĨŽƌtŚŝƚĞƚŽƉůĂLJϭ͘Ěϰ͕ ǁĞůů͘͟ʹGM Daniel King Ϯ͘EĨϯ͕ϯ͘Őϯ͕ϰ͘ŐϮ͕ϱ͘ϬͲϬĂŶĚŝŶŵŽƐƚĐĂƐĞƐϲ͘Đϰ͘ ͞&ŽƌĐŚĞƐƐĐŽĂĐŚĞƐƚŚŝƐŬŝƐŶŽƚŚŝŶŐƐŚŽƌƚŽĨƉŚĞŶŽŵĞŶĂů͘͟ ͞Ɛ/ƚŚŝŶŬƚŚĂƚ/ƐŚŽƵůĚŬĞĞƉŵLJĂĚǀŝĐĞ͚ƐŝŵƉůĞ͕͛/ǁŽƵůĚƐĂLJ -

Distributional Differences Between Human and Computer Play at Chess

Multidisciplinary Workshop on Advances in Preference Handling: Papers from the AAAI-14 Workshop Human and Computer Preferences at Chess Kenneth W. Regan Tamal Biswas Jason Zhou Department of CSE Department of CSE The Nichols School University at Buffalo University at Buffalo Buffalo, NY 14216 USA Amherst, NY 14260 USA Amherst, NY 14260 USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In our case the third parties are computer chess programs Distributional analysis of large data-sets of chess games analyzing the position and the played move, and the error played by humans and those played by computers shows the is the difference in analyzed value from its preferred move following differences in preferences and performance: when the two differ. We have run the computer analysis (1) The average error per move scales uniformly higher the to sufficient depth estimated to have strength at least equal more advantage is enjoyed by either side, with the effect to the top human players in our samples, depth significantly much sharper for humans than computers; greater than used in previous studies. We have replicated our (2) For almost any degree of advantage or disadvantage, a main human data set of 726,120 positions from tournaments human player has a significant 2–3% lower scoring expecta- played in 2010–2012 on each of four different programs: tion if it is his/her turn to move, than when the opponent is to Komodo 6, Stockfish DD (or 5), Houdini 4, and Rybka 3. move; the effect is nearly absent for computers. The first three finished 1-2-3 in the most recent Thoresen (3) Humans prefer to drive games into positions with fewer Chess Engine Competition, while Rybka 3 (to version 4.1) reasonable options and earlier resolutions, even when playing was the top program from 2008 to 2011. -

A Survey of Monte Carlo Tree Search Methods

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL INTELLIGENCE AND AI IN GAMES, VOL. 4, NO. 1, MARCH 2012 1 A Survey of Monte Carlo Tree Search Methods Cameron Browne, Member, IEEE, Edward Powley, Member, IEEE, Daniel Whitehouse, Member, IEEE, Simon Lucas, Senior Member, IEEE, Peter I. Cowling, Member, IEEE, Philipp Rohlfshagen, Stephen Tavener, Diego Perez, Spyridon Samothrakis and Simon Colton Abstract—Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is a recently proposed search method that combines the precision of tree search with the generality of random sampling. It has received considerable interest due to its spectacular success in the difficult problem of computer Go, but has also proved beneficial in a range of other domains. This paper is a survey of the literature to date, intended to provide a snapshot of the state of the art after the first five years of MCTS research. We outline the core algorithm’s derivation, impart some structure on the many variations and enhancements that have been proposed, and summarise the results from the key game and non-game domains to which MCTS methods have been applied. A number of open research questions indicate that the field is ripe for future work. Index Terms—Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), Upper Confidence Bounds (UCB), Upper Confidence Bounds for Trees (UCT), Bandit-based methods, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Game search, Computer Go. F 1 INTRODUCTION ONTE Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is a method for M finding optimal decisions in a given domain by taking random samples in the decision space and build- ing a search tree according to the results. It has already had a profound impact on Artificial Intelligence (AI) approaches for domains that can be represented as trees of sequential decisions, particularly games and planning problems. -

Extended Null-Move Reductions

Extended Null-Move Reductions Omid David-Tabibi1 and Nathan S. Netanyahu1,2 1 Department of Computer Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 52900, Israel [email protected], [email protected] 2 Center for Automation Research, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA [email protected] Abstract. In this paper we review the conventional versions of null- move pruning, and present our enhancements which allow for a deeper search with greater accuracy. While the conventional versions of null- move pruning use reduction values of R ≤ 3, we use an aggressive re- duction value of R = 4 within a verified adaptive configuration which maximizes the benefit from the more aggressive pruning, while limiting its tactical liabilities. Our experimental results using our grandmaster- level chess program, Falcon, show that our null-move reductions (NMR) outperform the conventional methods, with the tactical benefits of the deeper search dominating the deficiencies. Moreover, unlike standard null-move pruning, which fails badly in zugzwang positions, NMR is impervious to zugzwangs. Finally, the implementation of NMR in any program already using null-move pruning requires a modification of only a few lines of code. 1 Introduction Chess programs trying to search the same way humans think by generating “plausible” moves dominated until the mid-1970s. By using extensive chess knowledge at each node, these programs selected a few moves which they consid- ered plausible, and thus pruned large parts of the search tree. However, plausible- move generating programs had serious tactical shortcomings, and as soon as brute-force search programs such as Tech [17] and Chess 4.x [29] managed to reach depths of 5 plies and more, plausible-move generating programs fre- quently lost to brute-force searchers due to their tactical weaknesses. -

Deep Hiarcs 14 Uci Chess Engine Download

Deep Hiarcs 14 Uci Chess Engine Download Deep Hiarcs 14 Uci Chess Engine Download 1 / 3 14, Arics (WB), Vladimir Fadeev, Belarus, SD, 0,08, no ?? ... 22, Ifrit (UCI), Бренкман Андрей (Brenkman Andrey), Russia, 0,04, no, 2200, B1_6 B1_7 B1_9 ... 1. deep hiarcs 14 uci chess engine download 2. deep hiarcs chess explorer download o Deep HIARCS 14 WCSC (available with the Deep HIARCS Chess Explorer ... Please note you can add other UCI chess engines including third party UCI ... publisher is "Applied Computer Concepts Ltd.", do not trust the download if it is not ... deep hiarcs 14 uci chess engine download deep hiarcs 14 uci chess engine download, deep hiarcs chess explorer, deep hiarcs chess explorer download, deep hiarcs chess explorer for mac Red Giant VFX Suite 1.0.4 With Crack [Latest] Free download deep hiarcs 14 uci engine torrent Files at Software Informer. HIARCS 12 MP UCI - a chess program that can do more than .... See my blog for more information and download instructions. ... UCI parameters When an engine runs through a chess GUI, it communicates all the settings ... HIARCS14 (HIARCS book), TC 15sec; +8 -5 =7 First test with Lc0-v0. inf. exe (only ... AlphaZero; Deep Learning; Deus X; Leela Chess Zero; Forum Posts 2019. call of duty black ops crack indir oyuncehennemi multi.flash.kit.2.10.30 free download deep hiarcs chess explorer download Pinegrow Web Editor Crack 5.91 With keygen Free Download 2020 It connects a UCI chess engine to an xboard interface such as ... the AlphaZero-style Monte Carlo Tree Search and deep neural networks a flexible, .. -

Determining If You Should Use Fritz, Chessbase, Or Both Author: Mark Kaprielian Revised: 2015-04-06

Determining if you should use Fritz, ChessBase, or both Author: Mark Kaprielian Revised: 2015-04-06 Table of Contents I. Overview .................................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Not Discussed .......................................................................................................................................... 1 III. New information since previous versions of this document .................................................................... 1 IV. Chess Engines .......................................................................................................................................... 1 V. Why most ChessBase owners will want to purchase Fritz as well. ......................................................... 2 VI. Comparing the features ............................................................................................................................ 3 VII. Recommendations .................................................................................................................................... 4 VIII. Additional resources ................................................................................................................................ 4 End of Table of Contents I. Overview Fritz and ChessBase are software programs from the same company. Each has a specific focus, but overlap in some functionality. Both programs can be considered specialized interfaces that sit on top a