Move Similarity Analysis in Chess Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Videos Bearbeiten Im Überblick: Sieben Aktuelle VIDEOSCHNITT Werkzeuge Für Den Videoschnitt

Miller: Texttool-Allrounder Wego: Schicke Wetter-COMMUNITY-EDITIONManjaro i3: Arch-Derivat mit bereitet CSVs optimal auf S. 54 App für die Konsole S. 44 Tiling-Window-Manager S. 48 Frei kopieren und beliebig weiter verteilen ! 03.2016 03.2016 Guter Schnitt für Bild und Ton, eindrucksvolle Effekte, perfektes Mastering VIDEOSCHNITT Videos bearbeiten Im Überblick: Sieben aktuelle VIDEOSCHNITT Werkzeuge für den Videoschnitt unter Linux im Direktvergleich S. 10 • Veracrypt • Wego • Wego • Veracrypt • Pitivi & OpenShot: Einfach wie noch nie – die neue Generation der Videoschnitt-Werkzeuge S. 20 Lightworks: So kitzeln Sie optimale Ergebnisse aus der kostenlosen Free-Version heraus S. 26 Verschlüsselte Daten sicher verstecken S. 64 Glaubhafte Abstreitbarkeit: Wie Sie mit dem Truecrypt-Nachfolger • SQLiteStudio Stellarium Synology RT1900ac Veracrypt wichtige Daten unauffindbar in Hidden Volumes verbergen Stellarium erweitern S. 32 Workshop SQLiteStudio S. 78 Eigene Objekte und Landschaften Die komfortable Datenbankoberfläche ins virtuelle Planetarium einbinden für Alltagsprogramme auf dem Desktop Top-Distris • Anydesk • Miller PyChess • auf zwei Heft-DVDs ANYDESK • MILLER • PYCHESS • STELLARIUM • VERACRYPT • WEGO • • WEGO • VERACRYPT • STELLARIUM • PYCHESS • MILLER • ANYDESK EUR 8,50 EUR 9,35 sfr 17,00 EUR 10,85 EUR 11,05 EUR 11,05 2 DVD-10 03 www.linux-user.de Deutschland Österreich Schweiz Benelux Spanien Italien 4 196067 008502 03 Editorial Old and busted? Jörg Luther Chefredakteur Sehr geehrte Leserinnen und Leser, viele kleinere, innovative Distributionen seit einem Jahrzehnt kommen Desktop- Immer öfter stellen wir uns aber die haben damit erst gar nicht angefangen und Notebook-Systeme nur noch mit Frage, ob es wirklich noch Sinn ergibt, oder sparen es sich schon lange. Open- 64-Bit-CPUs, sodass sich die Zahl der moderne Distributionen überhaupt Suse verzichtet seit Leap 42.1 darauf; das 32-Bit-Systeme in freier Wildbahn lang- noch als 32-Bit-Images beizulegen. -

The 12Th Top Chess Engine Championship

TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship Article Accepted Version Haworth, G. and Hernandez, N. (2019) TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship. ICGA Journal, 41 (1). pp. 24-30. ISSN 1389-6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190090 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76985/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190090 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship Guy Haworth and Nelson Hernandez1 Reading, UK and Maryland, USA After the successes of TCEC Season 11 (Haworth and Hernandez, 2018a; TCEC, 2018), the Top Chess Engine Championship moved straight on to Season 12, starting April 18th 2018 with the same divisional structure if somewhat evolved. Five divisions, each of eight engines, played two or more ‘DRR’ double round robin phases each, with promotions and relegations following. Classic tempi gradually lengthened and the Premier division’s top two engines played a 100-game match to determine the Grand Champion. The strategy for the selection of mandated openings was finessed from division to division. -

Download the Booklet of Chessbase Magazine #199

THE Magazine for Professional Chess JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2021 | NO. 199 | 19,95 Euro S R V ON U I O D H E O 4 R N U A N DVD H N I T NG RE TIME: MO 17 years old, second place at the Altibox Norway Chess: Alireza Firouzja is already among the Top 20 TOP GRANDmasTERS ANNOTATE: ALL IN ONE: SEMI-TaRRasCH Duda, Edouard, Firouzja, Igor Stohl condenses a Giri, Nielsen, et al. trendy opening AVRO TOURNAMENT 1938 – LONDON SYSTEM – no reST FOR THE Bf4 CLash OF THE GENERATIONS Alexey Kuzmin hits with the Retrospective + 18 newly annotated active 5...Nh5!? Keres games THE MODERN BENONI UNDER FIRE! Patrick Zelbel presents a pointed repertoire with 6.Nf3/7.Bg5 THE MAGAZINE FOR PROFESSIONAL CHESS JANU 17 years old, secondARY / placeFEB at the RU Altibox Norway Chess: AlirezaAR FirouzjaY 2021 is already among the Top 20 NO . 199 1 2 0 2 G R U B M A H , H B M G E S DVD with first class training material for A B S S E club players and professionals! H C © EDITORIAL The new chess stars: Alireza Firouzja and Moscow in order to measure herself against Beth Harmon the world champion in a tournament. She is accompanied by a US official who warns Now the world and also the world of chess her about the Soviets and advises her not to has been hit by the long-feared “second speak with anyone. And what happens? She wave” of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many is welcomed with enthusiasm by the popu- tournaments have been cancelled. -

Game Changer

Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan Game Changer AlphaZero’s Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AI New In Chess 2019 Contents Explanation of symbols 6 Foreword by Garry Kasparov �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Introduction by Demis Hassabis 11 Preface 16 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 19 Part I AlphaZero’s history . 23 Chapter 1 A quick tour of computer chess competition 24 Chapter 2 ZeroZeroZero ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 33 Chapter 3 Demis Hassabis, DeepMind and AI 54 Part II Inside the box . 67 Chapter 4 How AlphaZero thinks 68 Chapter 5 AlphaZero’s style – meeting in the middle 87 Part III Themes in AlphaZero’s play . 131 Chapter 6 Introduction to our selected AlphaZero themes 132 Chapter 7 Piece mobility: outposts 137 Chapter 8 Piece mobility: activity 168 Chapter 9 Attacking the king: the march of the rook’s pawn 208 Chapter 10 Attacking the king: colour complexes 235 Chapter 11 Attacking the king: sacrifices for time, space and damage 276 Chapter 12 Attacking the king: opposite-side castling 299 Chapter 13 Attacking the king: defence 321 Part IV AlphaZero’s -

Chess Engine Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Kamil Klosowski

Chess Engine Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Kamil Klosowski 916847 May 2019 Abstract Reinforcement learning is one of the most rapidly developing areas of Artificial Intelligence. The goal of this project is to analyse, implement and try to improve on AlphaZero architecture presented by Google DeepMind team. To achieve this I explore different architectures and methods of training neural networks as well as techniques used for development of chess engines. Project Dissertation submitted to Swansea University in Partial Fulfilment for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Department of Computer Science Swansea University Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. May 13, 2019 Signed: Statement 1 This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a BSc in Computer Science. May 13, 2019 Signed: Statement 2 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are specifically acknowledged by clear cross referencing to author, work, and pages using the bibliography/references. I understand that fail- ure to do this amounts to plagiarism and will be considered grounds for failure of this dissertation and the degree examination as a whole. May 13, 2019 Signed: Statement 3 I hereby give consent for my dissertation to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. May 13, 2019 Signed: 1 Acknowledgment I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr Benjamin Mora for supervising this project and his respect and understanding of my preference for largely unsupervised work. -

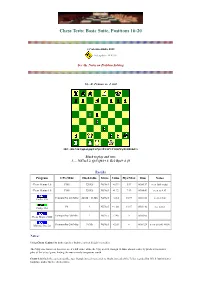

Chess Tests: Basic Suite, Positions 16-20

Chess Tests: Basic Suite, Positions 16-20 (c) Valentin Albillo, 2020 Last update: 14/01/98 See the Notes on Problem Solving 16.- Z. Franco vs. J. Gil FEN: rbb1N1k1/pp1n1ppp/8/2Pp4/3P4/4P3/P1Q2PPq/R1BR1K2/ b Black to play and win: 1. ... Nd7xc5 2. Qc5 Qh1+ 3. Ke2 Bg4+ 4. f3 Results Program CPU/Mhz Hash table Move Value Plys/Max Time Notes Chess Genius 1.0 P100 320 Kb Nd7xc5 +0.39 5/17 00:00:17 sees little value Chess Genius 1.0 P100 320 Kb Nd7xc5 +1.72 7/19 00:04:49 sees to 4. f3 Pentium Pro 200 MHz 24 Mb + 16 Mb Nd7xc5 +2.14 10/19 00:01:20 seen at 14s Crafty 12.6 P6 ? Nd7xc5 +1.181 11/17 00:01:46 see notes Crafty 13.3 Pentium Pro 200 Mhz ? Nd7xc5 +2.46 9 00:03:05 Chess Master 5500 Pentium Pro 200 Mhz 10 Mb Nd7xc5 +2.65 6 00:01:24 seen at 0:00, +0.00 MChess Pro 5.0 Notes: Using Chess Genius 1.0, both searches find the correct Knight's sacrifice. The 5-ply one, however, does not see it's full value, while the 7-ply search, though 16 times slower, correctly predicts the next 6 plies of the actual game, finding the move nearly two pawns worth. Crafty 12.6 finds the correct sacrifice too, though it needs to search to 10 ply, instead of the 7 plies required by CG1.0, but its better hardware makes for the shortest time. -

Draft – Not for Circulation

A Gross Miscarriage of Justice in Computer Chess by Dr. Søren Riis Introduction In June 2011 it was widely reported in the global media that the International Computer Games Association (ICGA) had found chess programmer International Master Vasik Rajlich in breach of the ICGA‟s annual World Computer Chess Championship (WCCC) tournament rule related to program originality. In the ICGA‟s accompanying report it was asserted that Rajlich‟s chess program Rybka contained “plagiarized” code from Fruit, a program authored by Fabien Letouzey of France. Some of the headlines reporting the charges and ruling in the media were “Computer Chess Champion Caught Injecting Performance-Enhancing Code”, “Computer Chess Reels from Biggest Sporting Scandal Since Ben Johnson” and “Czech Mate, Mr. Cheat”, accompanied by a photo of Rajlich and his wife at their wedding. In response, Rajlich claimed complete innocence and made it clear that he found the ICGA‟s investigatory process and conclusions to be biased and unprofessional, and the charges baseless and unworthy. He refused to be drawn into a protracted dispute with his accusers or mount a comprehensive defense. This article re-examines the case. With the support of an extensive technical report by Ed Schröder, author of chess program Rebel (World Computer Chess champion in 1991 and 1992) as well as support in the form of unpublished notes from chess programmer Sven Schüle, I argue that the ICGA‟s findings were misleading and its ruling lacked any sense of proportion. The purpose of this paper is to defend the reputation of Vasik Rajlich, whose innovative and influential program Rybka was in the vanguard of a mid-decade paradigm change within the computer chess community. -

Elo World, a Framework for Benchmarking Weak Chess Engines

Elo World, a framework for with a rating of 2000). If the true outcome (of e.g. a benchmarking weak chess tournament) doesn’t match the expected outcome, then both player’s scores are adjusted towards values engines that would have produced the expected result. Over time, scores thus become a more accurate reflection DR. TOM MURPHY VII PH.D. of players’ skill, while also allowing for players to change skill level. This system is carefully described CCS Concepts: • Evaluation methodologies → Tour- elsewhere, so we can just leave it at that. naments; • Chess → Being bad at it; The players need not be human, and in fact this can facilitate running many games and thereby getting Additional Key Words and Phrases: pawn, horse, bishop, arbitrarily accurate ratings. castle, queen, king The problem this paper addresses is that basically ACH Reference Format: all chess tournaments (whether with humans or com- Dr. Tom Murphy VII Ph.D.. 2019. Elo World, a framework puters or both) are between players who know how for benchmarking weak chess engines. 1, 1 (March 2019), to play chess, are interested in winning their games, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn and have some reasonable level of skill. This makes 1 INTRODUCTION it hard to give a rating to weak players: They just lose every single game and so tend towards a rating Fiddly bits aside, it is a solved problem to maintain of −∞.1 Even if other comparatively weak players a numeric skill rating of players for some game (for existed to participate in the tournament and occasion- example chess, but also sports, e-sports, probably ally lose to the player under study, it may still be dif- also z-sports if that’s a thing). -

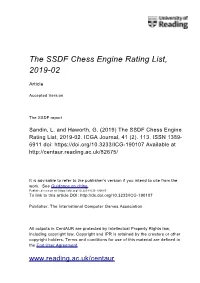

The SSDF Chess Engine Rating List, 2019-02

The SSDF Chess Engine Rating List, 2019-02 Article Accepted Version The SSDF report Sandin, L. and Haworth, G. (2019) The SSDF Chess Engine Rating List, 2019-02. ICGA Journal, 41 (2). 113. ISSN 1389- 6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190107 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/82675/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190085 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190107 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online THE SSDF RATING LIST 2019-02-28 148673 games played by 377 computers Rating + - Games Won Oppo ------ --- --- ----- --- ---- 1 Stockfish 9 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3494 32 -30 642 74% 3308 2 Komodo 12.3 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3456 30 -28 640 68% 3321 3 Stockfish 9 x64 Q6600 2.4 GHz 3446 50 -48 200 57% 3396 4 Stockfish 8 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3432 26 -24 1059 77% 3217 5 Stockfish 8 x64 Q6600 2.4 GHz 3418 38 -35 440 72% 3251 6 Komodo 11.01 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3397 23 -22 1134 72% 3229 7 Deep Shredder 13 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3360 25 -24 830 66% 3246 8 Booot 6.3.1 x64 1800X 3.6 GHz 3352 29 -29 560 54% 3319 9 Komodo 9.1 -

SHOWCASE BC 831 Funding Offers for BC Artists

SHOWCASE BC 831 Funding Offers for BC Artists Funding offers were sent to the following artists on April 17 + April 21, 2020. Artists have until May 15, 2020, to accept the grant. A Million Dollars in Pennies ArkenFire Booty EP Abraham Arkora BOSLEN ACTORS Art d’Ecco Bratboy Adam Bailie Art Napoleon Bre McDaniel Adam Charles Wilson Asha Diaz Brent Joseph Adam Rosenthal Asheida Brevner Adam Winn Ashleigh Adele Ball Bridal Party Adera A-SLAM Bring The Noise Adewolf Astrocolor Britt A.M. Adrian Chalifour Autogramm Brooke Maxwell A-DUB AutoHeart Bruce Coughlan Aggression Aza Nabuko Buckman Coe Aidan Knight Babe Corner Bukola Balogan Air Stranger Balkan Shmalkan Bunnie Alex Cuba bbno$ Bushido World Music Alex Little and The Suspicious Beamer Wigley C.R. Avery Minds Bear Mountain Cabins In The Clouds Alex Maher Bedouin Soundclash Caitlin Goulet Alexander Boynton Jr. Ben Cottrill Cam Blake Alexandria Maillot Ben Dunnill Cam Penner Alien Boys Ben Klick Camaro 67 Alisa Balogh Ben Rogers Capri Everitt Alpas Collective Beth Marie Anderson Caracas the Band Alpha Yaya Diallo Betty and The Kid Cari Burdett Amber Mae Biawanna Carlos Joe Costa Andrea Superstein Big John Bates Noirchestra Carmanah Andrew Judah Big Little Lions Carsen Gray Andrew Phelan Black Mountain Whiskey Carson Hoy Angela Harris Rebellion Caryn Fader Angie Faith Black Wizard Cassandra Maze Anklegod Blackberry Wood Cassidy Waring Annette Ducharme Blessed Cayla Brooke Antoinette Blonde Diamond Chamelion Antonio Larosa Blue J Ché Aimee Dorval Anu Davaasuren Blue Moon Marquee Checkmate -

Chessbase.Com - Chess News - Grandmasters and Global Growth

ChessBase.com - Chess News - Grandmasters and Global Growth Grandmasters and Global Growth 07.01.2010 Professor Kenneth Rogoff is a strong chess grandmaster, who also happens to be one of the world's leading economists. In a Project Syndicate article that appeared this week Ken sees the new decade as one in which "artificial intelligence hits escape velocity," with an economic impact on par with the emergence of India and China. He uses computer chess to illustrated the point. Grandmasters and Global Growth By Kenneth Rogoff As the global economy limps out of the last decade and enters a new one in 2010, what will be the next big driver of global growth? Here’s betting that the “teens” is a decade in which artificial intelligence hits escape velocity, and starts to have an economic impact on par with the emergence of India and China. Admittedly, my perspective is heavily colored by events in the world of chess, a game I once played at a professional level and still follow from a distance. Though special, computer chess nevertheless offers both a window into silicon evolution and a barometer of how people might adapt to it. A little bit of history might help. In 1996 and 1997, World Chess Champion Gary Kasparov played a pair of matches against an IBM computer named “Deep Blue.” At the time, Kasparov dominated world chess, in the same way that Tiger Woods – at least until recently – has dominated golf. In the 1996 match, Deep Blue stunned the champion by beating him in the first game. -

The TCEC Cup 2 Report

TCEC Cup 2 Article Accepted Version The TCEC Cup 2 report Haworth, G. and Hernandez, N. (2019) TCEC Cup 2. ICGA Journal, 41 (2). pp. 100-107. ISSN 1389-6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190104 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/81390/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: https://content.iospress.com/articles/icga-journal/icg190104 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190104 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online TCEC Cup 2 Guy Haworth and Nelson Hernandez1 Reading, UK and Maryland, USA The knockout format of TCEC Cup 1 (Haworth and Hernandez, 2019a/b) was well received by its audience and was adopted as a regular interlude between the TCEC Seasons’ Division P and Superfinal. TCEC Cup 2 was nested within TCEC14 (Haworth and Hernandez, 2019c/d) and began on January 17th 2019 with 32 chess engines and only a few minor changes from the inaugural Cup event. The ‘standard pairing’ was again used, with seed s playing seed 26-r-s+1 in round r if the wins all go to the higher seed.