Continuus Sta-Nine Zero,Pages.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor Lavey

The Rites of Lucifer On the altar of the Devil up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity. The Satanic ritual cham- ber is die ideal setting for the entertainment of unspoken thoughts or a veritable palace of perversity. Now one of the Devil's most devoted disciples gives a detailed account of all the traditional Satanic rituals. Here are the actual texts of such forbidden rites as the Black Mass and Satanic Baptisms for both adults and children. The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor LaVey The ultimate effect of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools. -Herbert Spencer - CONTENTS - INTRODUCTION 11 CONCERNING THE RITUALS 15 THE ORIGINAL PSYCHODRAMA-Le Messe Noir 31 L'AIR EPAIS-The Ceremony of the Stifling Air 54 THE SEVENTH SATANIC STATEMENT- Das Tierdrama 76 THE LAW OF THE TRAPEZOID-Die elektrischen Vorspiele 106 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN-Homage to Tchort 131 PILGRIMS OF THE AGE OF FIRE- The Statement of Shaitan 151 THE METAPHYSICS OF LOVECRAFT- The Ceremony of the Nine Angles and The Call to Cthulhu 173 THE SATANIC BAPTISMS-Adult Rite and Children's Ceremony 203 THE UNKNOWN KNOWN 219 The Satanic Rituals INTRODUCTION The rituals contained herein represent a degree of candor not usually found in a magical curriculum. They all have one thing in common-homage to the elements truly representative of the other side. The Devil and his works have long assumed many forms. Until recently, to Catholics, Protestants were devils. To Protes- tants, Catholics were devils. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

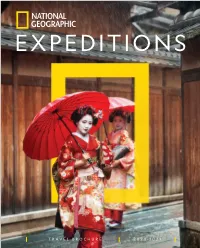

2 0 2 0–2 0 2 1 T R Av E L B R O C H U

2020–2021 R R ES E VE O BROCHURE NL INEAT VEL A NATGEOEXPE R T DI T IO NS.COM NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPEDITIONS NORTH AMERICA EURASIA 11 Alaska: Denali to Kenai Fjords 34 Trans-Siberian Rail Expedition 12 Canadian Rockies by Rail and Trail 36 Georgia and Armenia: Crossroads of Continents 13 Winter Wildlife in Yellowstone 14 Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks EUROPE 15 Grand Canyon, Bryce, and Zion 38 Norway’s Trains and Fjords National Parks 39 Iceland: Volcanoes, Glaciers, and Whales 16 Belize and Tikal Private Expedition 40 Ireland: Tales and Treasures of the Emerald Isle 41 Italy: Renaissance Cities and Tuscan Life SOUTH AMERICA 42 Swiss Trains and the Italian Lake District 17 Peru Private Expedition 44 Human Origins: Southwest France and 18 Ecuador Private Expedition Northern Spain 19 Exploring Patagonia 45 Greece: Wonders of an Ancient Empire 21 Patagonia Private Expedition 46 Greek Isles Private Expedition AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC ASIA 22 Australia Private Expedition 47 Japan Private Expedition 48 Inside Japan 50 China: Imperial Treasures and Natural Wonders AFRICA 52 China Private Expedition 23 The Great Apes of Uganda and Rwanda 53 Bhutan: Kingdom in the Clouds 24 Tanzania Private Expedition 55 Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: 25 On Safari: Tanzania’s Great Migration Treasures of Indochina 27 Southern Africa Safari by Private Air 29 Madagascar Private Expedition 30 Morocco: Legendary Cities and the Sahara RESOURCES AND MORE 31 Morocco Private Expedition 3 Discover the National Geographic Difference MIDDLE EAST 8 All the Ways to Travel with National Geographic 32 The Holy Land: Past, Present, and Future 2 +31 (0) 23 205 10 10 | TRAVELWITHNATGEO.COM For more than 130 years, we’ve sent our explorers across continents and into remote cultures, down to the oceans’ depths, and up the highest mountains, in an effort to better understand the world and our relationship to it. -

Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1906 Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906)." , (1906). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/513 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL, 1906 ISO PER YEAR ‘TF'TnTT^ PRICE 15 CENTS 180.5 THE ETUDE 209 MODERN SIX-HAND^ LU1T 1 I1 3 Instruction Books PIANO MUSIC “THE ETUDE” - April, 1906 Some Recent Publications Musical Life in New Orleans.. .Alice Graham 217 FOR. THE PIANOFORTE OF «OHE following ensemb Humor in Music. F.S.Law 218 IT styles, and are usi caching purposes t The American Composer. C. von Sternberg 219 CLAYTON F. SUMMY CO. _la- 1 „ net rtf th ’ standard foreign co Experiences of a Music Student in Germany in The following works for beginners at the piano are id some of the lat 1905...... Clarence V. Rawson 220 220 Wabash Avenue, Chicago. -

Bolsters I Unisia Army Battle; Stand Point Unsurd

TVr^r FRTDAT, CEGBMBWl 11, W «f dlattrbrif^ lEttrafno fEmtlft . w ' • ■ ■ ^ * 1 * 11 ATMrafft Daily Cireulatioii T h a W s a t lM r WSIf M M m 9m nOTCIBDVrf IVM * H ftonsnsts8P.8.WMh« Ummm . '^ - v . > , J f ' ^; k * 7,814 Membes nf Iha AndK J lw h noMss bsnlgbfl. ,1 CUMatlena Manehoster-rr^ Ctay of VUlago Chtarm # ' ■**)' ''*< ’ (Ctaasiae* AivertMag an rags U ) MANCHESTER, OONN„ SATURDAY, DECEBIBER 12,1942 (FOURTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CKr / *■ , V()L. LXIL, NO. 62 g&'ih>*ii<irabttlPi^T#^i'r w Tygfijnvtr Crewmen of U. S. S. San Francisco Line Rail Upon Arrival DOUBLE GREEN STAMPS j Battle for Elbow Bolsters Arm y f x i • • ____ . f Given In Dry Goods Dept’s. Oply, on Saturday | Of Don Renewed; I unisia Battle; mm0tmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmtmm»untnmim»uiimmmmMmmmmmmmm Soviets Advance Full Fashioned | Perfect Fitting I Axis Forces Launch Re Bad Effects Stand Point Unsurd RAYON peated Attacks on East Bank of River; O f Tornado San Francisco Allies Face Hard anc Reds Gain on Sec Babies Join Bloady Struggle tors of Both Stalingrad M ay B e Cut Story Proves Things War Foes’ Force of 28,( HTOIERY And Central Fronts. ki She«f'-qr 8emt-Sh««r weighta. Being Steadily Rein^ Cotton reinforced foot for extra forced; Probing wear. Moscow, Dec. 12.— {/F)— Hundreds of Volunteers Training Good Cuts Short The third battle for the el To Aid Weather Bu Line aV El Aghei bow of the Don river west of reau in Reporting Many. Orphanages . in Raises Possibility < Stalingrad appeared to be un Cruiser Home from Sol No Resistance Tht C der way today with Axis Approach of Storm, omons for Repair of Chicago Metropolitan forces launching repeated at Damage Suffered in Area Lack Enough Kansas City, Dec. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

For Summer Work, Pleasure and Sports at HIN & Iu ITS 29 59C

PXTIBW aatuiiratinr Caitninjit iimtOH nO D AT, JOWB M , 18B«. Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Wilks, of 16 AVWMHI D*n.X CXMOlILAnaii Walker street, are guests at the for the Moolk o f May, U M ABOUTTOWN Hotel Lincoln, la New Tork City. PHYSICAL DIRECTOR Mrs. Mary English of New Haven 5,819 U n . Owtruda QaUh of Bontoa Mwwetp tonight feOenad by gew- boot, « toachor Ja the BuckUnd Is spending the week with Mrs. PLANS EUROPE TOUR n M c o f the AndH ~~ ' hM laft for Travett, ICalna, Rebecca Wright o f lU HoU street eCi enlly fair and eaeler Snaday. aha will apand tha aummar, For Summer Work, Pleasure and Sports The name o f Lorraine Mitchell of MANCHESTER — A (.ITY OF VILLAGE CHARM the Washington school was not In a and who ara golo( to Clifford A. Gostafson, Teach VOL. L V , NO. 280. Nathan Hala camp and have cluded on the list furnished The MANCHESTER, CONN„ SATURDAY, JUNE 27, 1936. AlMnt in their appUcatlona, ara ra* Herald yesterday of pupils in the :i^MBtad to meat at tha Salvation elementary schools with perfect at er m Greenwich, to Sail Hale*s Present A Variety Of Fashions nny eltadal. Tuaaday momlnc at tendance for the school year of .. o’cloek, w lM they will leave for 108S-86. The addition of Miss J' >tte canq). Adjutant Valentina will Mitchell brought the total number Tomorrow. NAZIS LAY PLAN Welcoming: “ The Origrinal Roosevelt Man” ILvV'iffovlde tranaportatlon for thoael to 180. who require it. It ia important that White Wariiable . -

The Daily Egyptian, March 06, 1965

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC March 1965 Daily Egyptian 1965 3-6-1965 The aiD ly Egyptian, March 06, 1965 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_March1965 Volume 46, Issue 104 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, March 06, 1965." (Mar 1965). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1965 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in March 1965 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIU's Morris Li brory A Library: Many Things Southern's Rare Book ROl)m -Plus a Special Freedom -Photos, Story on page 6 By Floyd H. Stein appear or are mutilated about Keeping some materials out as fast as they're put on the of reach-but still available 'Shaping Education Policy' F:ceedom to read is impor shelves. Included are volumes "is a matter of common tant to Ralph E. McCoy. With dealing with abnorma'l sex sense, not ideology," says a book collection at the 900,000 practices. McCoy., , -A Review on page 5 mark. he has a special in "Since you can find these at The hbrary collectIons con- terest in such matters. corner drugstores," McCoy centrate in certain areas and Actually, the volumes aren't says, "it's silly to try to are contributing to the sta his. He's director of Southern keep them away from people ture oftheUniversityasacen So the Blind May 'Read' Illinois University Libraries using the libraries." ter of learning and research. -

Downing Association Newsletter and College Record

D OWNING D OWNING C OLLEGE 2017 C OLLEGE 2017 The Rose Garden Fountain Photograph by Tom Nagel Commended, Downing Alumni Association Photographic Competition. Front cover: Heong Gallery Exhibition – When Heavens meet the Earth Photography by Perry Hastings. Image courtesy The Heong Gallery. Our Latest Merchandise Watercolour of Downing c1920 Chef’s apron Men’s socks by Marco John’s Tote bag Downing tray The Rt Hon Sir David Lloyd Jones MA LLB President of the Association 2016–2017 Champagne flutes To purchase these items, please use the enclosed form or visit www.dow.cam.ac.uk/souvenirs. Or just type ‘Downing gifts’ into Google! DOWNING COLLEGE 2017 Alumni Association Newsletter Magenta News College Record C ONTENTS DOWNING COLLEGE A LUMNI A SSOCI ATION NEWSLETTER Officers and Committee 2016–2017 5 President’s Foreword 6 Association News 8 Next Year’s President 8 Contact with the Association 9 The 2016 Annual General Meeting 10 Other News from the Executive 12 The Alumni Student Fund 13 The Association Prize 14 Downing Alumni Association Photographic Competition 14 College News 16 The Master Writes 16 The Senior Tutor Writes 21 The Assistant Bursar’s Report 23 Forthcoming Events 25 Why does the College have an Art Gallery? 26 From the Archivist 29 ‘300 Years of Giving’ Since the Most Important Legacy of All 29 Future Archive Projects: Can you Help? 36 Remembering the First World War: One Hundred Years Ago 36 Features 45 “To Downing College” – Postscript 45 University Challenge 1975–76 45 Tour of Caen 48 College Cricket – not like Other -

Fine Books, Atlases & Manuscripts

FINE BOOKS, ATLASES & MANUSCRIPTS Wednesday 16 March 2016 Knightsbridge, London FINE BOOKS, ATLASES & MANUSCRIPTS FINE BOOKS, ATLASES | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 16 March 2016 16 March | Knightsbridge, London Wednesday 23459 226 92 37 FINE BOOKS, ATLASES AND MANUSCRIPTS Wednesday 16 March 2016 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES Please see page 2 for bidder Montpelier Street Matthew Haley information including after-sale Knightsbridge Simon Roberts collection and shipment. London SW7 1HH Luke Batterham www.bonhams.com Sarah Lindberg Please see back of catalogue Jennifer Ebrey for important notice to bidders VIEWING +44 (0) 20 7393 3828 Sunday 13 March +44 (0) 20 7393 3831 ILLUSTRATIONS 11am – 3pm Front cover: Lot Monday 14 March Shipping and Collections Back cover: Lot 9am – 4.30pm Leor Cohen Inside front cover: Lot Tuesday 15 March +44 (0) 20 7393 3841 Inside back cover: Lot 9am – 4.30pm [email protected] BIDS PRESS ENQUIRIES +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax To bid via the internet CUSTOMER SERVICES please visit www.bonhams.com Monday to Friday 8.30am – 6pm New bidders must also provide +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 proof of identity when submitting bids. Failure to do this may result in your bids not being processed. Please note that bids should be submitted no later than 4pm on LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS the day prior to the auction. AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE Please email [email protected] Bidding by telephone will only with “Live bidding” in the subject be accepted on a lot with a line up to 48 hours before the lower estimate of or in excess auction to register for this service. -

Berus-Lie Academic Spring Tournament (BLAST)

Berus-Lie Academic Spring Tournament (BLAST) Writers: Anishka Bandara, Anson Berns, Dylan Bowman, Katherine Lei, Michael Li, Steven Liu, Keaton Martin, Leela Mehta-Harwitz, Arjun Nageswaran, Mazin Omer, Hari Parameswaran, Darren Petrosino, Govind Prabhakar, Matthew Shu, Cole Snedeker, Ethan Strombeck, Chris Tong, Sophia Weng, Walter Zhang, Shawn Zhao Editors: Andrew Wang, Anson Berns, Katherine Lei, Michael Li, Keaton Martin, Hari Parameswaran, Vishwa Shanmugam Packet 1: Tossups 1. An analogue of this molecule with a fluorine-18 substitution is the most common radiotracer in PET scans. A phosphorylated derivative of this molecule is released by the action of debranching enzyme and phosphorylase. When high concentrations of this molecule are present, hemoglobin A1c [“A-one-see”] is formed. The first step in a process that breaks down this molecule phosphorylates it at the 6th position. Amylopectin and (*) amylose are formed from repeating units of this molecule. The pancreas secretes insulin in response to high concentrations of this molecule in the blood, and sucrose forms from the condensation of fructose and this molecule. For 10 points, name this molecule that is broken down in glycolysis, a six-carbon sugar. ANSWER: D-glucose [or dextrose or alpha-glucose, prompt on C6H12O6, prompt on sugar or monosaccharide] <KL, Biology> {Science, Biology} 2. In a collection by this composer, the melody of the last piece, “Remembrances,” is reused from the first, “Arietta.” Another work by this composer includes movements titled ‘Ingrid’s Lament” and “The Death of Åse.” The soloist enters after a crescendoing timpani roll in a work by this composer inspired by Robert Schumann's work of the same type and key, his Piano Concerto in A minor. -

Amplify Guide

AMPLIFY VOLUME 2: LESSONS 5 - 8 2015 - 2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN By Modest Mussorgsky (Russia) Romantic (1867) page 5 ASE’S DEATH (from the Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46) By Edvard Grieg (Norway) Romantic (1888) page 9 THE ENTERTAINER By Scott Joplin (USA) 20th Century (1902) page 13 MARS, BRINGER OF WAR (from The Planets, Op. 32) By Gustav Holst (England) 20th Century (1916) page 17 copyright 2015 Shreveport Symphony Orchestra www.shreveportsymphony.com 3 Who is this for? The Amplify curriculum is intended for use with upper elementary students (grades 3-5) but could be adapted for younger or older students. The curriculum can be taught in a general music education classroom, a specialized music class (e.g. band, orchestra), or an extracurricular setting. No prior experience in music is required on behalf of the participants. Who makes Amplify? Amplify is a program of the Shreveport Symphony Orchestra, which is offered free of charge thanks to generous underwriting by the Community Foundation of North Louisiana, the Caddo Parish School Board, and Chase Bank. What’s included in this guide? At the heart of the Amplify curriculum are eight featured musical works that represent a wide range of centuries, countries, and styles. This guide includes the second set of four lessons, which guide students through active listening exercises as they familiarize themselves with each piece. You can access the first set of lessons here. In the spring, a competition guide will help students make connections among the various pieces and help them prepare for the district-wide competition, in which they will listen to excerpts of the selected pieces and identify the title and composer.