The Foraging Ecology of Breeding Cape Cormorants P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cape Town

The effects of introduced mice on seabirds breeding at sub-Antarctic Islands Ben J. Dilley Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Town FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology DST/NRF Centre of Excellence Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science University of CapeCape Town of June 2018 University Supervised by Professor Peter G. Ryan The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Declaration This thesis reports original research that I conducted under the auspices of the FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town. All assistance received has been fully acknowledged. This work has not been submitted in any form for a degree at another university. ………………….................. Ben J. Dilley Cape Town, June 2018 i A 10 day-old great shearwater Ardenna gravis chick being attacked by an invasive House mouse Mus musculus in an underground burrow on Gough Island in 2014 (photo Ben Dilley). ii Table of Contents Page Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... vi Chapter 1 General introduction: Islands, mice and seabirds ......................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Clustered or dispersed: testing the effect of sampling strategy to census burrow-nesting petrels with varied distributions at sub-Antarctic Marion Island ...... 13 Chapter 3 Modest increases in densities of burrow-nesting petrels following the removal of cats Felis catus from sub-Antarctic Marion Island ................................... -

UNEP/CBD/RW/EBSA/SIO/1/4 26 June 2013

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/RW/EBSA/SIO/1/4 26 June 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH SOUTHERN INDIAN OCEAN REGIONAL WORKSHOP TO FACILITATE THE DESCRIPTION OF ECOLOGICALLY OR BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT MARINE AREAS Flic en Flac, Mauritius, 31 July to 3 August 2012 REPORT OF THE SOUTHERN INDIAN OCEAN REGIONAL WORKSHOP TO FACILITATE THE DESCRIPTION OF ECOLOGICALLY OR BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT MARINE AREAS1 INTRODUCTION 1. In paragraph 36 of decision X/29, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 10) requested the Executive Secretary to work with Parties and other Governments as well as competent organizations and regional initiatives, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), regional seas conventions and action plans, and, where appropriate, regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), with regard to fisheries management, to organize, including the setting of terms of reference, a series of regional workshops, with a primary objective to facilitate the description of ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs) through the application of scientific criteria in annex I of decision IX/20, and other relevant compatible and complementary nationally and intergovernmentally agreed scientific criteria, as well as the scientific guidance on the identification of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction, which meet the scientific criteria in annex I to decision IX/20. 2. In the same decision (paragraph 41), the Conference of the Parties requested that the Executive Secretary make available the scientific and technical data and information and results collated through the workshops referred to above to participating Parties, other Governments, intergovernmental agencies and the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA) for their use according to their competencies. -

Group Foraging in Socotra Cormorants: a Biologging Approach to the Study of a Complex Behavior Timothée R

Group foraging in Socotra cormorants: A biologging approach to the study of a complex behavior Timothée R. Cook, Rob Gubiani, Peter G. Ryan, Sabir B. Muzaffar To cite this version: Timothée R. Cook, Rob Gubiani, Peter G. Ryan, Sabir B. Muzaffar. Group foraging in Socotra cormorants: A biologging approach to the study of a complex behavior. Ecology and Evolution, Wiley Open Access, 2017, 7 (7), pp.2025-2038. 10.1002/ece3.2750. hal-01526388 HAL Id: hal-01526388 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01526388 Submitted on 23 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Received: 5 October 2016 | Revised: 6 December 2016 | Accepted: 22 December 2016 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.2750 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Group foraging in Socotra cormorants: A biologging approach to the study of a complex behavior Timothée R. Cook1,2 | Rob Gubiani3 | Peter G. Ryan2 | Sabir B. Muzaffar3 1Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Ecophysiology Abstract Team, Institute of Ecology and Environmental Group foraging contradicts classic ecological theory because intraspecific competition Sciences, University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France normally increases with aggregation. -

Rapid Radiation of Southern Ocean Shags in Response to Receding Sea Ice 2 3 Running Title: Blue-Eyed Shag Phylogeography 4 5 Nicolas J

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.18.456742; this version posted August 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 Rapid radiation of Southern Ocean shags in response to receding sea ice 2 3 Running title: Blue-eyed shag phylogeography 4 5 Nicolas J. Rawlence1, *, Alexander T. Salis1, 2, Hamish G. Spencer1, Jonathan M. Waters1, 6 Lachie Scarsbrook1, Richard A. Phillips3, Luciano Calderón4, Timothée R. Cook5, Charles- 7 André Bost6, Ludovic Dutoit1, Tania M. King1, Juan F. Masello7, Lisa J. Nupen8, Petra 8 Quillfeldt7, Norman Ratcliffe3, Peter G. Ryan5, Charlotte E. Till1, 9, Martyn Kennedy1,* 9 1 Department of Zoology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. 10 2 Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, University of Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. 11 3 British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, United Kingdom. 12 4 Instituto de Biología Agrícola de Mendoza (IBAM, CONICET-UNCuyo), Argentina. 13 5 FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, Department of Biological Sciences, University 14 of Cape Town, South Africa. 15 6 CEBC-CNRS, UMR 7372, 405 Route de Prissé la Charrière, 79360 Villiers en Bois, 16 France. 17 7 Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany. 18 8 Organisation for Tropical Studies, Skukuza, South Africa. 19 9 School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Arizona, USA. 20 21 Prepared for submission as a research article to Journal of Biogeography 22 23 * Corresponding authors: [email protected]; [email protected] 24 25 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 26 This work was supported with funding from the University of Otago. -

AMNH Digital Library

About 1.6 million people die of tuberculosis (TB) each year' mostly in developing nations lacking access to fast, accurate testing technology. TB is the current focus of the Foundation for Fino Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), established with ^" loundation ^ funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. for innovative new diagnostics FIND is dedicated to the advancement of diagnostic testing for infectious diseases in developing countries. For more information, visit www.finddiagnostics.org. Partnering against TB Twenty-two developing countries carry the burden culture from 42 days to as little as 10-14 days. In of 80 percent of the world's cases of TB, the addition, by identifying resistance to specific drugs, second-leading killer among infectious diseases the BD MGIT™ system provides fast and reliable and primary cause of death among people with information that can help physicians prescribe HIV/AIDS. The problem is compounded by TB's more effective treatments. All this can contribute resistance to drug treatment, limiting the options to the reduction in spread and mortality of TB, for over 450,000 patients annually. particularly in the HIV/AIDS population, where it is especially difficult to diagnose. BD is pleased to work with FIND to provide equipment, reagents, training and support to the Named one of America's Most Admired public health sector in high-burdened countries Companies' as well as one of the World's IVIost on terms that will enable them to purchase and Ethical Companies/ BD provides advanced medical implement these on a sustainable basis. technology to serve the global community's greatest needs. -

Government Notice No

Government Gazette REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Vol. 465 Pretoria 26 March 2004 No. 26189 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure STAATSKOERANT, 26 MAART 2004 No. 26189 3 GOVERNMENTNOTICE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS AND TOURISM No. 401 26 March 2004 SEA BIRDS AND SEALS PROTECTION ACT,1973 (ACT NO. 46 OF 1973) DRAFT POLICY FOR SEALS, SEABIRDS AND SHOREBlRDS IN SOUTH AFRICA TheMinister of EnvironmentalAffairs and Tourism has released a draft policy for seals, seabirds and shorebirds in South Africa. Members of the public are hereby invited to submit written comment on this draft policy. The drafl policy is available at www.deat.qov.za. Hard copies are available at the Department of EnvironmentalAffairs and Tourism: Branch Marine and Coastal Management, 5" Floor, Foretrust Building, Martin Hammerschlag Way, Foreshore Cape Town. Members of the public must submit written comment by no later than 16h00 on 31 May 2004. Comments should betied as follows: Draft Seals, Seabirds and Shorebirds Policy:2004 The Deputy Director-General: Marine and Coastal Management Comments may be - Hand delivered to the officesof Marine and Coastal Management at the above address; Posted by registered mail to Private BagX2, Roggebaai, 8012; E-mailed to [email protected]; or Faxed to (021) 425-7324. Should you have any telephonic enquiries, please do not hesitateto contact the Departmentat (021) 402-391 1, atternatively (021) 402-31 92. Your enquiries may be directedat Ms. Linda Staverees. 4 No. 26189 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 26 MARCH 2004 INTRODUCTION South African seabirds and seals are at present administered in terms of the Sea Birds and Seals Protection Act (SBSPA) No. -

Contemporary Wildlife Management Has Evolved in Recent Years

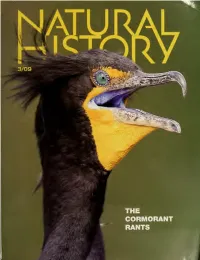

DIVING BEHAVIOR, PREDATOR-PREY DYNAMICS, AND MANAGEMENT EFFICACY OF DOUBLE-CRESTED CORMORANTS IN NEW YORK STATE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jeremy T. H. Coleman January 2009 © 2009 Jeremy T. H. Coleman DIVING BEHAVIOR, PREDATOR-PREY DYNAMICS, AND MANAGEMENT EFFICACY OF DOUBLE-CRESTED CORMORANTS IN NEW YORK STATE Jeremy T. H. Coleman, Ph.D. Cornell University 2009 The potential for a rapidly growing double-crested cormorant population to negatively impact fish populations and public resources in North America has focused attention on the feeding ecology and management of this federally protected species. Questions persist regarding the nature of cormorant-fish interactions and the propensity for cormorants to impact fish at the population level. From 1998 to 2003, we conducted research and participated in a management program at Oneida Lake, New York, that incorporated nest control and fall hazing to reduce cormorant populations on the lake. We examined: 1) the behavioral response of cormorants to the management program, 2) cormorant prey selectivity, 3) the impact of varying cormorant predation pressures on walleye and yellow perch populations, and 4) daily cormorant activity patterns and underwater foraging habits at Oneida Lake compared to other colonies in New York. I used radio telemetry and weekly counts to reveal that fall hazing moved cormorants off of Oneida Lake, reducing the September population annually by approximately 95% of the 1997 level. Most displaced cormorants relocated to nearby Onondaga Lake rather than leaving the region. -

Group Foraging in Socotra Cormorants: a Biologging Approach to the Study of a Complex Behavior

Received: 5 October 2016 | Revised: 6 December 2016 | Accepted: 22 December 2016 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.2750 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Group foraging in Socotra cormorants: A biologging approach to the study of a complex behavior Timothée R. Cook1,2 | Rob Gubiani3 | Peter G. Ryan2 | Sabir B. Muzaffar3 1Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Ecophysiology Abstract Team, Institute of Ecology and Environmental Group foraging contradicts classic ecological theory because intraspecific competition Sciences, University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France normally increases with aggregation. Hence, there should be evolutionary benefits to 2FitzPatrick Institute of African group foraging. The study of group foraging in the field remains challenging however, Ornithology, DST-NRF Centre of because of the large number of individuals involved and the remoteness of the interac- Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa tions to the observer. Biologging represents a cost- effective solution to these meth- 3Department of Biology, United Arab Emirates odological issues. By deploying GPS and temperature–depth loggers on individuals University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates over a period of several consecutive days, we investigated intraspecific foraging inter- Correspondence actions in the Socotra cormorant Phalacrocorax nigrogularis, a threatened colonial sea- Timothée R. Cook, Department of bird endemic to the Arabian Peninsula. In particular, we examined how closely birds Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Ecophysiology Team, Institute of Ecology and from the same colony associated with each other spatially when they were at sea at Environmental Sciences, University Pierre et the same time and the distance between foraging dives at different periods of the day. Marie Curie, Paris, France. Email: [email protected] Results show that the position of different birds overlapped substantially, all birds and targeting the same general foraging grounds throughout the day, likely following the Sabir B. -

The Seabirds and Seals Protection Act, 1973

STAATSKOERANT, 7 DESEMBER 2007 No. 30534 3 NOTICE 1717 OF 2007 DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS AND TOURISM MARINE LIVING RESOURCES ACT, 1998 (Act 18 of 1998) PUBLICATION OF POLICY ON THE MANAGEMENT OF SEALS, SEABIRDS AND SHOREBIRDS I, Marthinus van Schalkwyk, the Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, hereby publish the Policy on the Management of Seals, Seabirds and Shorebirds, schedule hereto, for general information. The policy will also be available on the Department's website at www.mcm-deat.qov.za. MARTHINUS VAN SCHALKWYK MINISTER OF ENVIRONMENTALAFFAIRS AND TOURISM Creamer Media Pty Ltd +27 11 622 3744 [email protected] www.polity.org.za 4 No. 30534 GOVERNMENT GAZElTE, 7 DECEMBER 2007 tal Affairs and Totlrtsm OF SOUTH AFRICA POLICY ON THE MANAGEMENT OF SEALS, SEABIRDS AND SHOREBIRDS: 2007 Creamer Media Pty Ltd +27 11 622 3744 [email protected] www.polity.org.za STAATSKOERANT, 7 DESEMBER 2007 No. 30534 5 Table of Contents 1. Definitions 2. Introduction 3. Purpose of the Policy 4. Objectives of the Policy 4.1 Management of Conservation of Seals, Seabirds and Shorebirds 4.1.1 Incidental Capture by Fisheries 4.1.2 Losses Due to Introduced Predators 4.1.3 Killing of Seals and Seabirds 4.1.4 Exploitation of Eggs 4.1.5 Insufficient Food 4.1.6 Displacement of Seabirds from Breeding Sites 4.1.7 Degradation of Breeding Habitat 4.1.8 Disturbance by Humans 4.1.9 Destruction of Nests 4.1.1 0 Oil Pollution 4.1.1 1 Other Forms of Pollution 4.2 Co-operative Management 4.2.1 Co-ordinated Management of South African Seal -

138 Macquarie Island Shag

Text and images extracted from Marchant, S. & Higgins, P.J. (co-ordinating editors) 1990. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to ducks; Part B, Australian pelican to ducks. Melbourne, Oxford University Press. Pages 737, 808-809, 867-872; plate 63. Reproduced with the permission of Bird life Australia and Jeff Davies. 737 Order PELECANIFORMES Medium-sized to very large aquatic birds of marine and inland waters. Worldwide distribution. Six families all breeding in our region. Feed mainly on aquatic animals including fish, arthropods and molluscs. Take-off from water aided by hopping or kicking with both feet together, in synchrony with wing-beat. Totipalmate (four toes connected by three webs). Hind toe rather long and turned inwards. Claws of feet curved and strong to aid in clambering up cliffs and trees. Body-down evenly distributed on both pterylae and apteria. Contour-feathers without after shaft, except slightly developed in Fregatidae. Pair of oil glands rather large and external opening tufted. Upper mandible has complex rhamphotheca of three or four plates. Pair of salt-glands or nasal glands recessed into underside of frontal bone (not upper side as in other saltwater birds) (Schmidt-Nielson 1959; Siegel Causey 1990). Salt-glands drain via ducts under rhamphotheca at tip of upper mandible. Moist throat-lining used for evaporative cooling aided by rapid gular-flutter of hyoid bones. Tongue rudimentary, but somewhat larger in Phaethontidae. Throat, oesophagus and stomach united in a distensible gullet. Undigested food remains are regurgitated. Only fluids pass pyloric sphincter. Sexually dimorphic plumage only in Anhingidae and Fregatidae. -

Environmental Impact Assessment of Electromagnetic Techniques Used for Oil & Gas Exploration & Production

Environmental Impact Assessment of Electromagnetic Techniques Used for Oil & Gas Exploration & Production September 2011 Environmental Impact Assessment of Electromagnetic Techniques Used for Oil & Gas Exploration & Production Prepared by R.A. Buchanan, M.Sc. (Project Manager), R. Fechhelm, Ph.D. (Electromagnetics and Fishes), P. Abgrall, Ph.D. (Marine Mammals), and A.L. Lang, Ph.D. (Seabirds) LGL Limited environmental research associates P.O. Box 13248, Stn. A St. John’s, NL A1B 4A5 Tel: 709-754-1992 [email protected] Prepared for International Association of Geophysical Contractors 1225 North Loop West, Suite 220 Houston, TX 77008 USA September 2011 LGL Project No. SA1084 Suggested format for citation: Buchanan, R.A., R. Fechhelm, P. Abgrall, and A.L. Lang. 2011. Environmental Impact Assessment of Electromagnetic Techniques Used for Oil & Gas Exploration & Production. LGL Rep. SA1084. Rep. by LGL Limited, St. John’s, NL, for International Association of Geophysical Contractors, Houston, Texas. 132 p. + app. EIA of Electromagnetic Techniques Used for Oil & Gas Exploration & Production EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In October 2010, LGL Limited environmental research associates (LGL) of St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada was contracted by the International Association of Geophysical Contractors (IAGC) to prepare an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of electromagnetic (EM) techniques used for oil and gas exploration and production in the marine environment. The goal of the EIA is to provide a comprehensive resource summarizing available literature and potential effects of EM technologies for a broad audience. IAGC members may also use the EIA to optimize environmental protection plans (EPPs) associated with their EM activities. The EIA focuses on EM technologies that are currently being used to search for resistivity anomalies around the world: Controlled-Source Electromagnetics (CSEM) and Multi-Transient Electromagnetics (MTEM). -

Read Book Cormorance Kindle

CORMORANCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nick Hayes | 184 pages | 20 Oct 2016 | Vintage Publishing | 9781910702055 | English | London, United Kingdom Cormorance PDF Book As one of the world's oldest and largest ornithological societies, AOS produces scientific publications of the highest quality, hosts intellectually engaging and professionally vital meetings, serves ornithologists at every career stage, pursues a global perspective, and informs public policy on all issues important to ornithology and ornithological collections. I adored every minute. Limicorallus , meanwhile, was initially believed to be a rail or a dabbling duck by some. Want to Read saving…. Nov 20, Michelle rated it liked it. Most travel probably by day. Look up cormorant in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Migrates in flocks, often following coastlines or rivers. How do cormorants feed? However this gland is not efficient enough so cormorants are quite often seen with their wings spread out in or to dry them. Even his relationship with Lucy is somewhat fraught, and Strike finds himself becoming closer to Robin, who has always wanted to be a detective, than he at first feels entirely comfortable with. Double-crested cormorant white-crested cormorant Neotropic cormorant olivaceous cormorant Little black cormorant Great cormorant White- breasted cormorant Indian cormorant Cape cormorant Socotra cormorant Bank cormorant Wahlberg's cormorant Japanese cormorant Temminck's cormorant European shag Brandt's cormorant Spectacled cormorant Pelagic cormorant Baird's cormorant Red-faced cormorant Rock shag Guanay cormorant Pied cormorant yellow-faced cormorant Black-faced cormorant Rough-faced shag king shag Foveaux shag Otago shag Chatham shag Auckland shag Campbell shag Bounty shag Imperial shag blue-eyed shag Heard Island shag Crozet shag Antarctic shag Kerguelen shag Macquarie shag South Georgia shag Red-legged cormorant Spotted shag Pitt shag Featherstone's shag Little pied cormorant Long-tailed cormorant Crowned cormorant Little cormorant Pygmy cormorant Flightless cormorant.