How the EU Is Facing Crises in Its Neighbourhood Evidence from Libya and Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Strategy for Success in Libya

A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Why the US Must Act in Libya Now ............................................................................................................................1 Wrong Problem, Wrong Strategy ............................................................................................................................... 2 What to Do ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Reframing US Policy in Libya .................................................................................................. 5 America’s Opportunity in Libya ................................................................................................................................. 6 The US Approach in Libya ............................................................................................................................................ 6 The Current Situation -

Briefing Notes 1 July 2013

Asylum and Migration Information Centre Briefing Notes 1 July 2013 Iraq Security situation On 24.06.13, a series of bomb attacks killed at least 39 people in Baghdad. On 25.06.13, a blast in Tuz Khurmato (Salahuddin province) killed at least 11 and injured 55. The attack was targeted against people protesting against the security situation and the dire living conditions in the city. On 27.06.13, attacks were launched in the cities of Baghdad and Baqubah (Diyala province), in Babil province and also in the city of Mosul (Ninive province), killing a total of 34 people and wounding approx. 90. On 28.06.13, at least 10 people lost their lives in Anbar Province when two bombs were detonated. On 29.06.13, at least 28 people were killed and approx. five were wounded in fights occurring in Baghdad and Ninive and in Anbar, Saladin and Diyala provinces. On 30.06.13, attacks in Baghdad, Basra (Basra province), Mosul, Hilla (Babil province) and Kut (Wassit province) claimed the lives of at least 23 people, injuring 30. UN Special Envoy to Iraq takes stock on his term of office Near the end of his mission in Iraq, UN Special Envoy Martin Kobler voiced worry over rising levels of violence and worsening sectarianism, press reports said. The Sunni-Shiite conflict was „paralyzing the whole country“, he stated. However, he also noted some signs of progress, such as the improving ties with Kuwait, to which Iraq is still paying reparations, and elections that have largely been deemed free and fair. -

Libya: Military Actors and Militias

Libya: military actors and militias By Francesco Finucci With special thanks to Lucia Polvanesi, for her editing work Photo: BRQ Network/Flickr The aftermath After Qaddafi's fall, about 200000 militiamen took to the streets. It was the end of a 40 years lasting regime. But it was also the first step towards the chaos: a country dominated by militias, fulfilled with weapons and characterized by harsh territories, where paratroops could hide themselves for months. Moreover, evidences suggest the use of this chaos in order to cover conflicts between rival tribes. Actions already blamed as war crimes. Hope is a fundamental element to be considered in new Libya, but fear is as well. What emerged from this study is a complicated scenario, much more than expected. On the other hand, requests are numerous and often genuine. The will to build a better place to live in came to light as well as the simple effort to gain power. Exploring this lively and intense underworld is not simple, even without being on the spot. Violence is part of this scenario as well as sense of the State. Sometimes they merge, sometimes they clash, but they never disappear. Probably, they won't do it for years, until Libya will be mature for military and political stability. After entering inside the last two years of Libyan history, we can't help hoping for this. Francesco Finucci Loyalty Name Flag/Symbol State-affiliated Libyan Army Force: 35000 soldiers1. القوات المسلحة الليبية Bodies The new army risen after Qaddafi's fall seems to be partially composed by former military staff, Allies: Libya Shield; and the detained equipment level is about the National Mobile Force; same as militias weaponry standard. -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building LIBYA

G N I N I A R T T N E M E C R O F N E W A L LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING FOR CAPACITY BUILDING Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building LIBYA Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Version 1.2) 1 Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 20/12/2017 SSSA Overall structure and first draft 1.1 23/02/2018 SSSA Second version after internal feedback among SSSA staff 1.2 10/05/2018 SSSA Final version version before feedback from partners LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER1.2 WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER V.1.2 2 LIBYA Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Claudia KNERING, under the scientific supervision of Professor Andrea de GUTTRY and Dr. Annalisa CRETA. Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy www.santannapisa.it LET4CAP, co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. -

EUBAM Libya Initial Mapping Report Executive Summary

RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED Council of the European Union Brussels, 25 January 2017 (OR. en) 5616/17 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED CIVCOM 13 COPS 23 CFSP/PESC 55 CSDP/PSDC 34 RELEX 51 JAI 64 MAMA 17 COAFR 27 EUBAM LIBYA 2 COVER NOTE From: European External Action Service To: Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management Subject: EUBAM Libya Initial Mapping Report Executive Summary Delegations will find attached document EEAS(2017) 0109. Encl.: EEAS(2017) 0109 5616/17 AK/ils DGC 2B RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED EN EEAS(2017) 0109 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED EUROPEAN EXTERNAL ACTION SERVICE CPCC Working document of the European External Action Service of 24/01/2017 EEAS Reference EEAS(2017) 0109 Classification RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED To Committee for the Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management Title / Subject EUBAM Libya Initial Mapping Report Executive Summary [Ref. prev. doc.] N/A EEAS(2017) 0109 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED EUBAM-LIBYA INITIAL MAPPING REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EUBAM-Libya produced an Initial Mapping Report on interim findings in accordance with its mandate to map the different Libyan actors that have a stake in the following priority areas: border security, counter-terrorism, organised crime and migration, as well as the wider law enforcement area and the criminal justice chain. The objective is to provide Member States with an update on the state of play prior to the upcoming Six-Monthly Report and the EUBAM-Libya Strategic Review in the spring of 2017. The mapping exercise is proving to be challenging as these sectors, to a large extent to date, are driven by individual actors instead of legitimate state institutions. -

Political Situation

Libya Last update: 20 maart 2020 Population: 6,678,567 million (World Bank 2018 est.) Prime minister: Fayez al-Sarraj Governemental type: - Ruling coalition: - Last election: 25 June 2014 (Council of Deputies) Next election: - Sister parties: None Subsequently to the Tunisian uprising, first protests in Libya started halfway January 2011. One month later, the protests had turned into the most violent conflict between government and citizens among the different Arab uprisings at that time. After almost 42 years under the regime of Gaddafi the people of Libya found a momentum to take over control of their country. But what started as a popular uprising and outcry for political reform quickly turned into factional violence. The newly elected General National Congress (GNC) in 2012 tried to hold the country together. The rise of Islamic State in Libya and the contested 2014 elections resulted in the creation of a rival government in the eastern city of Tobruk. A second Civil War ensued. The reconciliation process initiated by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) has so far failed to unite the country. The current internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), based in the original capital Tripoli, has limited power, while the HoR supported by Libyan National Army of general Khalifa Haftar rules more than half of the country. Political Situation Libya gained independence in December 1951 after being under UN supervision as Italy lost the territory during World War II. Following a military coup in 1969, Colonel Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi designed his own political system, the Third Universal Theory, later dubbing the country the ‘Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya’. -

2014 NIS Libya ENG.Pdf

Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. Through more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of of the European Union. Authors: Voluntas Advisory, Diwan Market Research and Nordic Consulting Group © Cover photo: BBC World Service Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of December 2014. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN: 978-3-96076-020-7 © 2016 Transparency International. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION 2 II. ABOUT THE NATIONAL INTE-GRITY SYSTEM ASSESSMENT 4 III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 IV. COUNTRY PROFILE: FOUNDATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL INTEGRITY SYSTEM 17 V. CORRUPTION PROFILE 24 VI. ANTI-CORRUPTION ACTIVITIES 28 VII. NATIONAL INTEGRITY SYSTEM 30 1. LEGISLATURE 32 2. EXECUTIVE 46 3. JUDICIARY 58 4. PUBLIC SECTOR 721 5. LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES 87 6. ELECTORAL MANAGEMENT BODY 98 7. SUPREME AUDIT INSTITUTION 112 8. ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCY 123 9. POLITICAL PARTIES 133 10. MEDIA 147 11. CIVIL SOCIETY 160 12. BUSINESS 169 VIII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 186 IX. BIBLIOGRAPHY 199 I. INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION A National Integrity System Assessments is a tool developed by Transparency International to evaluate a country’s integrity system, namely the legal safeguards it has in place against corruption and how these work in practice. -

Libya: the Growth of Conflict on Narrow Interests Threatens the Fragile State

Position Paper Libya: The growth of conflict on narrow interests threatens the fragile state This paper was originally written in Arabic by: Al Jazeera Center for Studies Translated into English by: The Afro-Middle East Centre (AMEC) Al Jazeera Centre for Studies 29 August 2013 Tel: +974-40158384 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.n Source (Aljazeera) The Libyan scene, far from achieving political consensus, is dominated by political divisions between the Islamists, liberals, and armed forces that represent interregional and specific tribal agendas. Moreover, this situation exists in the context of regional tension and weak transitional governmental institutions. These institutions require political and revolutionary leaders that recognise that the goals of the revolution and ultimately state-building and peace, can only be achieved through consensus. There has been recurrent news about the deteriorating security situation in Libya, and in the cities of Benghazi and Tripoli in particular. Hardly a day passes without reports of acts of violence or clashes between armed parties, in addition to disappearances and ransom-motivated kidnapping. This has prompted local and international human rights organisations to describe the abuses as violations of human rights. Libyan activists have further stated that the violations are worse than those that prevailed under Muammar Gaddafi, and responsibility for this cannot only be assigned to the so-called ‘Gaddafi arrows.’ The current deteriorating situation appears in the context of regional tensions, especially in Egypt and Tunisia, and the escalation of the threat of al-Qa’ida and transnational organised crime. These threats prompted the Libyan authorities to work in coordination with both Tunisia and Algeria to confront these armed groups. -

Yearbook-On-Peace-Processes-2015

School of Culture of Peace 2015 yearbook of peace processes Vicenç Fisas (ed.) Icaria editorial 1 Printing: Romanyà Valls, SA Design: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: 978-84-9888-654-2 Legal Deposit: B-9288-2012 This yearbook was written by Vicenç Fisas, Director of the UAB’s School for a Culture of Peace. The author would like to express his gratitude for the information provided by numerous members of the School’s research team, especially Josep María Royo, Jordi Urgell, Pamela Urrutia, Ana Villellas and María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas also holds the UNESCO Chair in Peace and Human Rights at the UAB. He has a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford, won the National Human Rights Award in 1988, and is the author of over 30 books on conflicts, disarmament and research into peace. Some of his published titles include Manual de procesos de paz (Handbook of Peace Processes), Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados (Peace Processes and Negotiation in Armed Conflicts), La paz es posible (Peace is Possible) and Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos (Peace Culture and Conflict Management). 2 CONTENTS Introduction: definitions and categories …………………………………………………………0505 The main stages in a peace process……………………………………………………………..0606 Usual stages in negotiation processes……………………………………………………………0808 Main conclusions of the year……………………………………………………………………..0909 Peace processes in 2014…………………………………………………………… ……………..1313 Conflicts and peace processes at the end of 2014 …………………………………………………1616 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years…………………………………………………..1717 -

Libya Country Report BTI 2016

BTI 2016 | Libya Country Report Status Index 1-10 2.64 # 124 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 2.38 # 126 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 2.89 # 119 of 129 Management Index 1-10 2.47 # 121 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2016. It covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2015. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2016 — Libya Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2016 | Libya 2 Key Indicators Population M 6.3 HDI 0.784 GDP p.c., PPP $ 15590.8 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.1 HDI rank of 187 55 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 75.4 UN Education Index 0.698 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 78.4 Gender inequality2 0.215 Aid per capita $ 20.7 Sources (as of October 2015): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2015 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2014. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.10 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Libya has been in the throes of a civil war since the launch of the 17 February 2011 revolution which overthrew Colonel Muammar al-Qadhafi after 42 years in power. -

Libyan Political Economy

www.gsdrc.org [email protected] Helpdesk Research Report Libyan Political Economy Iffat Idris 18.07.2016 Question Give an update of key actors, dynamics and issues of Libyan political economy since the 2014 GSDRC report1 on the same topic. Contents 1. Overview 2. Key developments since 2014 3. Significant actors 4. Major dynamics and issues 5. References 1. Overview Much has changed in Libya since April 2014 – there have been significant political developments, new actors have emerged and others have been eclipsed. However, the fundamentals have not changed: Libya remains highly unstable and divided along multiple fracture lines, there are still a multitude of non- armed groups and even more armed groups, and relations between them continue to be extremely fluid. Given this, the literature on the country situation becomes quickly outdated. The main political development has been the establishment of two rival governments following contested elections in June 2014: a reconvened General National Congress (GNC) based in Tripoli and the House of Representatives (HoR) based in Tobruk. Coalitions of armed groups back each side: Operation Dignity opposed to Islamists and aligned to the HoR and Operation Libya Dawn coalition formed in response, comprising of Islamist groups and others supporting the GNC. In December 2015 the UN- backed Libya Political Agreement (LPA) was signed between representatives of both governments, setting up a Government of National Accord (GNA) with an executive Presidency Council. The Council established itself in Tripoli early this year (2016), but both the GNC and HoR persist – meaning Libya has three rival claimants to power. 1 Combaz, E. -

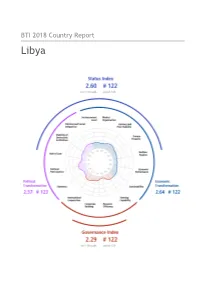

Libya Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Libya This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Libya. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Libya 3 Key Indicators Population M 6.3 HDI 0.716 GDP p.c., PPP $ - Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.9 HDI rank of 188 102 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 71.8 UN Education Index 0.650 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 78.8 Gender inequality2 0.167 Aid per capita $ 25.3 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Libya has been immersed in civil war since the 17 February 2011 revolution which led to Colonel Muammar al-Qadhafi’s ouster after 42 years in power.