Libyan Political Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 ! ! ! TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 ESSAY ONE COMPETING JIHADIST ORGANISATIONS AND NETWORKS 6 Islamic State, Al-Qaeda, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar al-Sharia in Libya Stefano Torelli and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY TWO POLITICAL PARTY OR ARMED FACTION? 31 The Future of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood Valentina Colombo, Giuseppe Dentice and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY THREE MAPPING RADICAL ISLAMIST MILITIAS IN LIBYA 53 Wolfgang Pusztai and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY FOUR THE EXPLOITATION OF MIGRATION ROUTES TO EUROPE 73 Human Trafficking Through Areas of Libya Affected by Fundamentalism Nancy Porsia ABOUT THE AUTHORS 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 2 LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL 3 DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS FOREWORD ! ! This publication is a compilation of four different essays, edited by Dr. Arturo Varvelli PhD, which from part of a series of studies undertaken by EFD to analyse the nature and spread of the phenomenon of radicalisation in the European Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods. It focuses on Libya and assesses the current situation on the ground through a number of diverse and varied prisms. It identifies patterns and trends as well as specific local and regional developments in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the situation of radicalisation in post-Ghadaffi Libya and the extent to which this may be contributing to regional as well as international instability Months of acute political turmoil in Libya following the fall of the Qaddafi regime, compounded by a weak national identity as well as legacies from the civil war in 2011 which ended Qaddafi’s 42-year rule, have resulted in Libya becoming a failed state with a strong radical Islamist presence. -

A Strategy for Success in Libya

A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Why the US Must Act in Libya Now ............................................................................................................................1 Wrong Problem, Wrong Strategy ............................................................................................................................... 2 What to Do ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Reframing US Policy in Libya .................................................................................................. 5 America’s Opportunity in Libya ................................................................................................................................. 6 The US Approach in Libya ............................................................................................................................................ 6 The Current Situation -

How the EU Is Facing Crises in Its Neighbourhood Evidence from Libya and Ukraine

How the EU is facing crises in its neighbourhood Evidence from Libya and Ukraine Deliverable 6.1 (Version 1; 31.03.2017) Prepared by: Project acronym: EUNPACK Project full title: Good intentions, mixed results – A conflict sensitive unpacking of the EU comprehensive approach to conflict and crisis mechanisms Grant agreement no.: 693337 Type of action: Research and Innovation Action Project start date: 01 April 2016 Project duration: 36 months Call topic: H2020-INT-05-2015 Project website: www.eunpack.eu Document: How the EU is facing crises in its neighbourhood: evidence from Libya and Ukraine Deliverable number: 6.1 Deliverable title: Working paper on EU policies towards Libya and Ukraine Due date of deliverable: 31.03.2017 Actual submission date: 31.03.2017 Editors: Luca Raineri, Alessandra Russo, Anne Harrington Authors: Kateryna Ivashchenko-Stadnik, Roman Petrov, Luca Raineri, Pernille Rieker, Alessandra Russo, Francesco Strazzari Reviewers: Morten Bøås, Participating beneficiaries: SSSUP, JMCK, NUPI, IRMC Work Package no.: 6 Work Package title: Crisis response in the neighbourhood area Work Package leader: Francesco Strazzari Work Package participants: SSSUP, JMCK, NUPI, IRMC, UManchester Estimated person‐months for deliverable: 5 Dissemination level: Public Nature: Report Version: 1 Draft/Final: Final No. of pages (including cover): 65 Keywords: European neighbourhood, Libya, Ukraine, crisis 2 How the EU is facing crises in its neighbourhood Evidence from Libya and Ukraine EUNPACK Paper Kateryna Ivashchenko-Stadnik, Roman Petrov, Luca Raineri, Pernille Rieker, Alessandra Russo, 1 Francesco Strazzari 1 This paper was prepared in the context of the EUNPACK project (A conflict-sensitive unpacking of the EU comprehensive approach to conflict and crises mechanism), funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. -

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2256 Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War by Andrew Engel May 20, 2014 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Andrew Engel Andrew Engel, a former research assistant at The Washington Institute, recently received his master's degree in security studies at Georgetown University and currently works as an Africa analyst. Brief Analysis Long-simmering tensions between non-Islamist and Islamist forces have boiled over into military actions centered around Benghazi and Tripoli, entrenching the country's rival alliances and bringing them ever closer to civil war. n May 16, former Libyan army general Khalifa Haftar launched "Operation Dignity of Libya" in Benghazi, O aiming to "c leanse the city of terrorists." The move came three months after he announced the overthrow of the government but failed to act on his proclamation. Since Friday, however, army units loyal to Haftar have actively defied armed forces chief of staff Maj. Gen. Salem al-Obeidi, who called the operation "a coup." And on Monday, sympathetic forces based in Zintan extended the operation to Tripoli. These and other developments are edging the country closer to civil war, complicating U.S. efforts to stabilize post-Qadhafi Libya. DIVIDING LINES I slamists and non-Islamist forces have long been contesting each other's claims to being the legitimate heart of the 2011 revolution. Islamist factions such as the Muslim Brotherhood-related Justice and Construction Party and the Loyalty to the Martyrs Bloc have dominated the General National Congress (GNC) since summer 2013, when the forcibly passed Political Isolation Law effectively barred all former Qadhafi regime members -- even those who had fought the regime -- from participating in government for ten years. -

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYIA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 About the European Foundation for Democracy The European Foundation for Democracy is a Brussels-based policy institute dedicated to upholding Europe’s fundamental values of freedom and equality, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion. Today these principles are being challenged by a number of factors, among them rapid social change as a result of high levels of immigration from cultures with different customs, a rise in intolerance on all sides, an increasing sense of a conflict of civilisations and the growing influence of radical, extremist ideologies worldwide. We work with grassroots activists, media, policy experts and government officials throughout Europe to identify constructive approaches to addressing these challenges. Our goal is to ensure that the universal values of the Enlightenment –religious tolerance, political pluralism, individual liberty and government by demo- cracy – remain the core foundation of Europe’s prosperity and welfare, and the basis on which diverse cultures and opinions can interact peacefully. About the Counter Extremism Project The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) is a not-for-profit, non-partisan, international policy organization formed to address the threat from extremist ideology. It does so by pressuring financial support networks, countering the narrative of extremists and their online recruitment, and advocating for effective laws, policies and regula- tions. CEP uses its research and analytical expertise to build a global movement against the threat to pluralism, peace and tolerance posed by extremism of all types. In the United States, CEP is based in New York City with a team in Washington, D.C. -

January 2021 Libya Emergency Type: Complex Emergency Reporting Period: 01.01.2021 to 31.01.2021

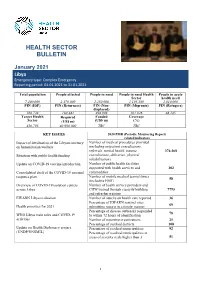

HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN January 2021 Libya Emergency type: Complex Emergency Reporting period: 01.01.2021 to 31.01.2021 Total population People affected People in need People in need Health People in acute Sector health need 7,400,000 2,470,000 1,250,000 1,195,389 1,010,000 PIN (IDP) PIN (Returnees) PIN (Non- PIN (Migrants) PIN (Refugees) displaced) 168,728 180,482 498,908 301,026 46,245 Target Health Required Funded Coverage Sector (US$ m) (US$ m) (%) 450,795 40,990,000 TBC TBC KEY ISSUES 2020 PMR (Periodic Monitoring Report) related indicators Impact of devaluation of the Libyan currency Number of medical procedures provided on humanitarian workers (including outpatient consultations, referrals, mental health, trauma 376.468 Situation with public health funding consultations, deliveries, physical rehabilitation) Update on COVID-19 vaccine introduction Number of public health facilities supported with health services and 302 Consolidated draft of the COVID-19 national commodities response plan. Number of mobile medical teams/clinics 58 (including EMT) Overview of COVID-19 isolation centers Number of health service providers and across Libya CHW trained through capacity building 7793 and refresher training EWARN Libya evaluation Number of attacks on health care reported 36 Percentage of EWARN sentinel sites 68 Health priorities for 2021 submitting reports in a timely manner Percentage of disease outbreaks responded 78 WHO Libya main roles and COVID-19 to within 72 hours of identification activities Number of reporting organizations 25 Percentage of reached districts 100 Update on Health Diplomacy project Percentage of reached municipalities 92 (UNDP/UNSMIL) Percentage of reached municipalities in areas of severity scale higher than 3 51 1 HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN January 2021 SITUATION OVERVIEW • The UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called on foreign fighters and mercenaries in Libya to immediately leave because "the Libyans have already proven that, left alone, they are able to address their problems". -

Minority Ethnic Groups

Country Information and Guidance Libya: Minority ethnic groups 18 February 2015 Preface This document provides guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling claims made by nationals/residents of - as well as country of origin information (COI) about - Libya. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Within this instruction, links to specific guidance are those on the Home Office’s internal system. Public versions of these documents are available at https://www.gov.uk/immigration- operational-guidance/asylum-policy. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. -

Origins of the Libyan Conflict and Options for Its Resolution

ORIGINS OF THE LIBYAN CONFLICT AND OPTIONS FOR ITS RESOLUTION JONATHAN M. WINER MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-12 CONTENTS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 4 HISTORICAL FACTORS * 7 PRIMARY DOMESTIC ACTORS * 10 PRIMARY FOREIGN ACTORS * 11 UNDERLYING CONDITIONS FUELING CONFLICT * 12 PRECIPITATING EVENTS LEADING TO OPEN CONFLICT * 12 MITIGATING FACTORS * 14 THE SKHIRAT PROCESS LEADING TO THE LPA * 15 POST-SKHIRAT BALANCE OF POWER * 18 MOVING BEYOND SKHIRAT: POLITICAL AGREEMENT OR STALLING FOR TIME? * 20 THE CURRENT CONFLICT * 22 PATHWAYS TO END CONFLICT SUMMARY After 42 years during which Muammar Gaddafi controlled all power in Libya, since the 2011 uprising, Libyans, fragmented by geography, tribe, ideology, and history, have resisted having anyone, foreigner or Libyan, telling them what to do. In the process, they have frustrated the efforts of outsiders to help them rebuild institutions at the national level, preferring instead to maintain control locally when they have it, often supported by foreign backers. Despite General Khalifa Hifter’s ongoing attempt in 2019 to conquer Tripoli by military force, Libya’s best chance for progress remains a unified international approach built on near complete alignment among international actors, supporting Libyans convening as a whole to address political, security, and economic issues at the same time. While the tracks can be separate, progress is required on all three for any of them to work in the long run. But first the country will need to find a way to pull back from the confrontation created by General Hifter. © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. -

Security Council Provisional Asdfsixty-Ninth Year 7194Th Meeting Monday, 9 June 2014, 10.10 A.M

United Nations S/ PV.7194 Security Council Provisional asdfSixty-ninth year 7194th meeting Monday, 9 June 2014, 10.10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Churkin ..................................... (Russian Federation) Members: Argentina ....................................... Mrs. Perceval Australia ........................................ Mr. White Chad ........................................... Mr. Cherif Chile ........................................... Mr. Llanos China .......................................... Mr. Shen Bo France .......................................... Mr. Araud Jordan .......................................... Mr. Hmoud Lithuania ........................................ Mr. Kalindra Luxembourg ..................................... Ms. Lucas Nigeria ......................................... Mr. Laro Republic of Korea ................................. Ms. Paik Ji-ah Rwanda ......................................... Mr. Gasana United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .... Sir Mark Lyall Grant United States of America ........................... Mrs. DiCarlo Agenda The situation in Libya This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting -

1/7 November 2014 UNHCR POSITION ON

November 2014 UNHCR POSITION ON RETURNS TO LIBYA Introduction 1. Since the overthrow of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and his government in October 2011, Libya has been affected by a chronic state of insecurity.1 In a climate of instability and chaos, the country has seen intense clashes between armed groups and almost daily assassinations, bombings and kidnappings. The presence of numerous militias – some reports indicate that there are up to 1,700 different armed groups2 – each reported to control certain areas of territory, have left successive governments struggling to exercise authority in those areas. The many armed groups are reported to be ideologically divided and are said to be split along geographical lines in the country. Analysts have expressed concerns about the risk of Libya descending into civil war.3 Intense fighting between rival armed groups takes its toll on civilians, as hundreds of thousands have been forcibly displaced across the country, vital infrastructure has been destroyed and the humanitarian situation is rapidly deteriorating.4 Recent Political Developments (2014) 2. Social unrest, evidenced, inter alia, by demonstrations, armed clashes, and an increase in kidnappings and killings has been reported in Libya in a climate of deteriorating security. Since January 2014, Libya has had rapid succession in the Executive branch that is closely linked to the increasingly divided political landscape. In February 2014, protests erupted when the parliament, the General National Congress (GNC), cited the need for drafting a new constitution and extended its mandate beyond 7 February 2014. On 16 May 2014, the situation further deteriorated when a former General, Khalifa Haftar,5 launched a military offensive against armed groups in Benghazi. -

Anupropaz A2016.Pdf

Impresión: Diseño: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Depósito Legal: B-14.344.2008 Este anuario ha sido elaborado por Vicenç Fisas, director de la Escola de Cultura de Pau de la UAB. El autor agradece la información facilitada por varias personas del equipo de investigación de la Escola, particularmente Ana Ballesteros, Iván Navarro, Josep Maria Royo, Jordi Urgell, Pamela Urrutia, Ana Villellas y María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas es también doctor en estudios sobre paz por la Universidad de Bradford, premio Nacional de Derechos Humanos 1988 y autor de más de treinta libros sobre conflictos, desarme, investigación sobre la paz o procesos depaz. Algunos de los títulos publicados son: Diplomacias de paz: negociar con grupos armados; Manual de procesos de paz; Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados; La paz es posible; y Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos. Índice Glosario 7 Europa 195 a) Sudeste de Europa 195 Presentación: definiciones y tipologías 13 Chipre 195 Kosovo 201 Fases habituales en los procesos de Moldova (Transdniestria) 208 negociación 15 Turquía (PKK) 213 Ucrania 223 Principales conclusiones del año 19 b) Cáucaso 233 Armenia-Azerbaiyán 233 Los procesos de paz en 2015 26 Georgia (Abjasia y Osetia del Sur) 238 Los conflictos y los procesos de paz al Oriente Medio 245 finalizar 2015 27 Israel-Palestina 245 Los conflictos y los procesos de paz de los últimos años 31 Análisis por países Anexos África 31 1. Procesos analizados en los capítulos a) África Occidental 31 de los anuarios, de 2006 a 2016. 253 Malí (Tuaregs) 31 Senegal (Casamance) 38 2. Acuerdos de paz y ratificación del Estatuto b) Cuerno de África 42 de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional.