Parasitoids of Chrysopidae Eggs in Sinaloa Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewed Erature to Ensure the Most Up-To-Date Treatment with Caution, P~Rticularlyamong Older Literature

PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 39-114. December 9, 1997 SPECIES CATALOG OF THE NEUROPTERA, MEGALOPTERA, AND RAPHIDIOPTERA OF AMERlCA NORTH OF MEXICO Norman D. Penny Department ofE~ztorizolog)~,Caldornla Acndony oJ'Sc~erzces, San Fmnc~sco,CA 941 18 Phillip A. Adams Ccllg'rnia State Utzivet-sity, F~lllet-ton,CA 92634 and Lionel A. Stange Florida Depat>tnzen/oj'Agt.~czi/trrre, Gr~~nesv~/le, FL 32602 Thc 399 currently recognized valid species of the orders Neuroptera, Megaloptera, and Raphidioptera that are known to occur in America north of Mexico are listed and full synonymies given. Geographical distributions are listed by states and province\. Complete bibliographic references are given for all namcs and nomenclatural acts. Included are two new Junior homonyms indicated, seven new taxonomic cornbinations, two new changes of rank, fourteen new synonymies, three new lectotype de\ignations, and onc new name. Received March 20,1996. Accepted June 3, 1997. The recent publication of Nomina Insecta been consulted whenever possible, as well as Nearctica, A Check List of the Insects of North Zoological Record, and appropriate mono- America (Poole 1996) has given us a listing of graphic revisions publishedup to 1 January 1997. North American Neuropterida (Neuroptera + A number of taxonomic changes are incorpo- Megaloptera + Raphidioptera) species for the rated into this catalog: there are two new Junior first tlme in more than a century. However, for homonyms indicated, seven new taxonomic anyone trying to identify these species, the litera- combinations, two new changes of rank. fourteen ture is scattered and obscure. -

Megaloptera, Sialidae)

MUSEUM & INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES FRAGMENTA FAUN I STIC A Fragm. faun. Warsaw, 30.12.2000 43 11 123-125 Wiesława C z e c h o w s k a Sialis morio K lingstedt, 1932 Megaloptera( , S ia lid a), e an alderfly species new to Poland Abstract: Sialis morio K lingstedt, 1932 is reported from Poland for the first time. It was found in two sites in the Masurian Lake District in the years 1998-1999. Key words:Neuropteroidea, Megaloptera , Sialis morio, Poland. Author's address: Museum and Institute of Zoology, PAS, Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warszawa, POLAND The Megaloptera is a small order of insects of the superorder Neuropteroi dea whose larval development occurs in an aquatic habitat. In Europe, this taxon is represented by 10 species of the genus Sialis L a t r . , the family Siali dae (A s p ó c k et al. 1980, V s h iv k o v a 1985, 1987). However, according to A s p ó c k (1992) and A s p ó c k and H o l z e l (1994), this genus should be revised, for some of the recently described species may be synonyms of others. The species considered unquestionable by these authors include Sialis lutaria L., S. morio K l i n g s t . , S. sordida K l i n g s t . , S. fuliginosa PICT., S. rtigripes PICT, and S. sibirica M c L a c h l . Three of these have been recorded from Poland, namely S. -

Creek Critters!

Grades 3-6 Creek Critter Activity Page 1 ter Protect Ot Ou lly r W ea a R t e e r W ! Creek Critters! Science With Spokane County Water Resources Help the trout f This belongs to: ind the ca ly! Fish, like the Redband Trout, eat aquatic bugs known as AQUATIC ddisf MACROINVERTEBRATES (macros for short). Macros live at the bottom of streams, rivers and lakes for most of their lives; some even live several years! The types of macros you find in a waterway can tell you how clean or dirty the water is! Scientists do field studies to collect and identify macros to monitor how healthy our local waterways are. Can you think of some macros you’ve seen before? Aquatic= live in the water Macro = large enough to see by the naked eye invertebrates = animals with no backbone Macroinvertebrates Using the word bank, write the name of the life phase on the blue line. DRAGONFLY LIFE CYCLE COLOR ME! Macro Life Cycle Most of the macros you’ll find in creeks are juvenile (child) larvae or pupa that look very different from adults. Many live most of their lives underwater, until their final molting stage when their exoskeleton cracks open and wings emerge to become flying adults for the Word Bank last part of their life cycles. Laying eggs Larva/nymph Adult Egg Molting 6 months Lives in water 3-4 years before hatching in the larval stage Eggs Lives 2-4 months on Molting into an land as adults adult with wings Grades 3-6 Creek Critter Activity Page 2 Table Manners! Freshwater Food Chain Macros have specialized mouth pieces to help them gather food or hunt. -

Biodiversity and Phenology of the Epibenthic Macroinvertebrate Fauna in a First Order Mississippi Stream

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 Biodiversity and Phenology of the Epibenthic Macroinvertebrate Fauna in a First Order Mississippi Stream Jamaal Bankhead University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Bankhead, Jamaal, "Biodiversity and Phenology of the Epibenthic Macroinvertebrate Fauna in a First Order Mississippi Stream" (2017). Master's Theses. 308. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/308 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIODIVERSITY AND PHENOLOGY OF THE EPIBENTHIC MACROINVERTEBRATES FAUNA IN A FIRST ORDER MISSISSIPPI STREAM by Jamaal Lashwan Bankhead A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Science and Technology, and the Department of Biological Sciences at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2017 BIODIVERSITY AND PHENOLOGY OF THE EPIBENTHIC MACROINVERTEBRATES FAUNA IN A FIRST ORDER MISSISSIPPI STREAM by Jamaal Lashwan Bankhead August 2017 Approved by: ________________________________________________ Dr. David C. Beckett, Committee Chair Professor, Biological Sciences ________________________________________________ Dr. Kevin Kuehn, Committee -

MAINE STREAM EXPLORERS Photo: Theb’S/FLCKR Photo

MAINE STREAM EXPLORERS Photo: TheB’s/FLCKR Photo: A treasure hunt to find healthy streams in Maine Authors Tom Danielson, Ph.D. ‐ Maine Department of Environmental Protection Kaila Danielson ‐ Kents Hill High School Katie Goodwin ‐ AmeriCorps Environmental Steward serving with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection Stream Explorers Coordinators Sally Stockwell ‐ Maine Audubon Hannah Young ‐ Maine Audubon Sarah Haggerty ‐ Maine Audubon Stream Explorers Partners Alanna Doughty ‐ Lakes Environmental Association Brie Holme ‐ Portland Water District Carina Brown ‐ Portland Water District Kristin Feindel ‐ Maine Department of Environmental Protection Maggie Welch ‐ Lakes Environmental Association Tom Danielson, Ph.D. ‐ Maine Department of Environmental Protection Image Credits This guide would not have been possible with the extremely talented naturalists that made these amazing photographs. These images were either open for non‐commercial use and/or were used by permission of the photographers. Please do not use these images for other purposes without contacting the photographers. Most images were edited by Kaila Danielson. Most images of macroinvertebrates were provided by Macroinvertebrates.org, with exception of the following images: Biodiversity Institute of Ontario ‐ Amphipod Brandon Woo (bugguide.net) – adult Alderfly (Sialis), adult water penny (Psephenus herricki) and adult water snipe fly (Atherix) Don Chandler (buigguide.net) ‐ Anax junius naiad Fresh Water Gastropods of North America – Amnicola and Ferrissia rivularis -

Analysis of the Deconstruction of Dyke Marsh, George Washington

Analysis of the Deconstruction of Dyke Marsh, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Virginia: Progression, Geologic and Manmade Causes, and Effective Restoration Scenarios Dyke Marsh image credit: NASA Open-File Report 2010-1269 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: Hurricane Isabel approaching landfall, September 17, 2003. The storm’s travel path is shaded, and trends from southeast to north-northwest. The initial cloud bands from Isabel are arriving at Dyke Marsh in this image. Base imagery taken from a LANDSAT 5 visible image; see appendix 3A. Analysis of the Deconstruction of Dyke Marsh, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Virginia: Progression, Geologic and Manmade Causes, and Effective Restoration Scenarios By Ronald J. Litwin, Joseph P. Smoot, Milan J. Pavich, Helaine W. Markewich, Erik Oberg, Ben Helwig, Brent Steury, Vincent L. Santucci, Nancy J. Durika, Nancy B. Rybicki, Katharina M. Engelhardt, Geoffrey Sanders, Stacey Verardo, Andrew J. Elmore, and Joseph Gilmer Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Open-File Report 2010–1269 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Don't Let Water Quality Bug You out (PDF)

UI Extension Forestry Information Series II Water Quality No. 8 Don’t Let Water Quality Bug You Out Randy Brooks Using insects to monitor water quality may sound bone (invertebrate). BMI’s inhabit all types of running like something from a Far Side cartoon, but in real- waters, from fast-flowing mountain streams to slow- ity, bugs are a “quick and dirty” method of assessing moving muddy rivers. Examples of aquatic macroin- water quality. The traditional water quality monitor- vertebrates include insects (in their larval or nymph ing approach has been to collect stream water samples form), crayfish, clams, snails, and worms. Most live and have them analyzed for physical and chemical partly or nearly all of their life cycle attached to sub- contaminants. Since water sampling and analysis is merged rocks, logs, and vegetation. expensive, insect monitoring is a more economical and There are three groups (taxa) of BMI’s: quicker method of determining water quality. In the U.S., much as canaries are used in mineshafts, the use • Group one BMI’s are pollution sensitive and of stream organisms as biological indicators of wa- found in good quality water. This group in- ter quality has become widespread over the past few cludes stonefly larvae, caddisfly larvae, water decades. pennies, riffle beetles, mayfly larvae, gilled snails, and dobsonfly larvae. Biological monitoring is used to assess a water body’s • Group Two BMI’s are somewhat pollution environmental conditions. One type of biological tolerant organisms that can be found in good or monitoring is a biological survey or biosurvey (also fair quality water. -

CADDISFLIES: Six Legs, Often in a Hardened Case of Mineral Or Organic Matter, 11

CADDISFLIES: Six legs, often in a hardened case of mineral or organic matter, 11. 12. may be ‘free living’ and not in a case. Head distinctly hardened and often patterned, hooks at the end of body, may or may not have gills along abdomen. FREE LIVERS 11. Net Spinning Caddisflies: ‘C’ shaped in the pan, bushy gills underneath body and at tail, builds a retreat to hide in (commonly silken nets with wood or gravel anchors). Net spinners have a head as wide as the thorax of the body. 12. Small Head Caddisflies: These insects resemble net spinners, but have no gills under the body 13. 14. and a much narrower head. They may be white, green or brown, with a fat body and rapid ‘inch-worm’ movement. ORGANIC CASE 13. Stick Bait Caddisflies: 1” – 3” including case, dark brown spots on their yellowish heads. These caddis may be distinguished from other wood and stick cased caddis by the prominent ‘ballast’ pieces of sticks that are attached to the sides of the case. 15. 16. 14. Square Log Cabin Caddisflies: Cases are stouter than other square cases, constructed from wound strips of wood fibers, as opposed to fragments of leaves. Insects greenish or cream colored, prominent brushes of seta on the first pair of legs. 15. Sand and Stick Case Caddisflies: Cases constructed from both mineral and organic materials 17. 18. belong in this category and may be a variety of shapes and sizes. 16. Vegetated Case Caddisflies: This category is for all caddisflies with organic cases that do not fit the other categories above. -

Megaloptera of Canada 393 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.819.23948 REVIEW ARTICLE Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 819: 393–396 (2019) Megaloptera of Canada 393 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.819.23948 REVIEW ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Megaloptera of Canada Xingyue Liu1 1 Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China Corresponding author: Xingyue Liu ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Langor | Received 29 January 2018 | Accepted 2 March 2018 | Published 24 January 2019 http://zoobank.org/E0BA7FB8-0318-4AC1-8892-C9AE978F90A7 Citation: Liu X (2019) Megaloptera of Canada. In: Langor DW, Sheffield CS (Eds) The Biota of Canada – A Biodiversity Assessment. Part 1: The Terrestrial Arthropods. ZooKeys 819: 393–396.https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.819.23948 Abstract An updated summary on the fauna of Canadian Megaloptera is provided. Currently, 18 species are re- corded in Canada, with six species of Corydalidae and 12 species of Sialidae. This is an increase of two species since 1979. An additional seven species are expected to be discovered in Canada. Barcode Index Numbers are available for ten Canadian species. Keywords alderflies, biodiversity assessment, Biota of Canada, dobsonflies, fishflies, Megaloptera The order Megaloptera (dobsonflies, fishflies, and alderflies) is one of the three orders of Neuropterida, and is characterized by the prognathous adult head, the broad anal area of hind wing and the exclusively aquatic larval stages (New and Theischinger 1993). Currently, there are ca. 380 described species of Megaloptera worldwide (Yang and Liu 2010, Oswald 2016). Extant Megaloptera are composed of only two families; Corydalidae, which is divided into Corydalinae (dobsonflies) and Chauliodinae (fish- flies), and Sialidae (alderflies). -

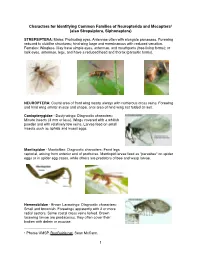

Characters for Identifying Common Families of Neuropterida and Mecoptera1 (Also Strepsiptera, Siphonaptera)

Characters for Identifying Common Families of Neuropterida and Mecoptera1 (also Strepsiptera, Siphonaptera) STREPSIPTERA: Males: Protruding eyes. Antennae often with elongate processes. Forewing reduced to clublike structures; hind wing large and membranous with reduced venation. Females: Wingless. May have simple eyes, antennae, and mouthparts (free-living forms); or lack eyes, antennae, legs, and have a reduced head and thorax (parasitic forms). NEUROPTERA: Costal area of front wing nearly always with numerous cross veins. Forewing and hind wing similar in size and shape, anal area of hind wing not folded at rest. Coniopterygidae - Dusty-wings: Diagnostic characters: Minute insects (3 mm or less). Wings covered with a whitish powder and with relatively few veins. Larvae feed on small insects such as aphids and insect eggs. Mantispidae - Mantisflies: Diagnostic characters: Front legs raptorial, arising from anterior end of prothorax. Mantispid larvae feed as "parasites" on spider eggs or in spider egg cases, while others are predators of bee and wasp larvae. Hemerobiidae - Brown Lacewings: Diagnostic characters: Small and brownish. Forewings apparently with 2 or more radial sectors. Some costal cross veins forked. Brown lacewing larvae are predaceous, they often cover their bodies with debris or exuviae. 1 Photos UMSP, BugGuide.net, Sean McCann. !1 Chrysopidae - Green Lacewings: Diagnostic characters: All (or nearly all) costal cross veins simple. Sc and R1 in forewing not fused near wing tip. Wings usually greenish. The larvae, or aphidlions, are predators of small insects and some also carry debris. Adults have tiny tympanna on the forewing base. Eggs are laid on long stalks. Adults are common at porch lights in summer. -

Aquatic Insect Family Tree

Aquatic Insect Family Tree Aquatic insects are like other insects. cacarryararrryrr itsiti own o house oof pebbles and sticks They have six legs, threeee bobody segments, everywhere it goes! antennae, and sometimestim wings. They also Aquatic insects are different in one way have an exoskeletonon (a skeleton on the from the insinsects we see on land. They are outside of the body).ody). That helps them movmove adapted to liveve part of their lives underwater. food and objectsts much heavier than thetheir This family tree showsho some of the aquatic own weight. A caddisfly larvae can mmake and insect groups. Kingdom: Phylum: Class: Animalia Arthropoda Insecta (animals) (jointed-foot invertebrates) (insects) Mayflies (Ephemeroptera) Stoneflies (Plecoptera) Giant stonefly nymph; roach stonefly nymph; common stonefly nymph Left to right: Burrowing mayfly nymph; minnow mayfly nymph; flat-headed mayfly nymph Dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata) Above: Common stonefly nymph Left to right: Dragonfly nymph; damsel- fly nymph Alderflies, dobsons and fishflies True bugs (Hemiptera) (Megaloptera) Left to right: Dobsonfly larva (hellgrammite); alderfly larva Caddisflies (Trichoptera) Top to bottom (left to right): Water strider; water boatman; backswim- mer; water scorpion; giant water bug True flies (Diptera) Cranefly larva; mosquito larvae; blackfly larva Top: Stick case-maker caddisfly larva Bottom left to right: Stone case-maker caddisfly larva; net- spinning caddisfly larva Left to right: Cranefly larva; blackfly larva Beetles (Coleoptera) Left to right: Water penny (larva); whirligig beetle; predaceous diving beetle. -

All Aquatic Insect Fact Sheets

Spring 2006 by Walt Dietz Anglers sometimes wonder which bait to Aquatic insects are more than food for use when fishing. Most of us are familiar fish. They are also important in the aquatic with baits like corn, cheese and dough balls. ecosystem. Some are predators. They eat We might also use live baits like minnows or other insects and small fish. Other aquatic worms. But there is another bait. It’s easy insects eat plants. Still others are the to collect. You can even wait until you get garbage collectors of the stream because they to your fishing spot to obtain it. Do you eat dead animals and litter (dead plants, have any idea what it might be? Here is a leaves and debris). Some scientists even use clue: Lift a rock the next time you go fish- aquatic insects to tell them about the quality ing. Then take a close look. of the water—just like a canary in a coal You guessed right if you were thinking mine. They measure how many kinds of "aquatic insects." Bass, panfish, trout, carp, insects live in certain waterways and how suckers and catfish eat aquatic insects. many of each kind of insect live there. There are plenty of these tasty treats in our Let's take a closer look at aquatic ponds, streams and rivers. There are lots of insects—where they live, their life cycle and different kinds and sizes. how we can use them for bait. ? Rainbow trout ? photo-Art Michaels photo-Art Which one should I eat? ? ? Aquatic Insect Family Tree Aquatic insects are like other insects.