Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chiapas Earthquake, Mexico 2017

GEOFILE Extension 781 The Chiapas earthquake, Mexico 2017 By Philippa Simmons Synopsis Links This Geofile will explore the causes and impacts of Exam board Link to specification the Chiapas earthquake that occurred in Mexico in AQA September 2017, as well as the responses to it. Mexico AS Component 1 Physical Geography 3.3.1.4 is situated where the Cocos plate converges with the Seismic hazards p18 pdf version North American plate – one of the most tectonically Click here active regions in the world, with up to 40 earthquakes A2 Component 1 Physical Geography 3.1.5.4 a day. The state of Chiapas is located along the Seismic hazards p15 pdf version Click here southern shore of Mexico and borders Guatemala, it is in a subduction zone and is at risk of strong Edexcel AS 1.4c and 1.5c Social and economic impacts of earthquakes. At 23.49 local time on 7 September 2017 tectonic hazards p18 pdf version an earthquake of magnitude 8.2 struck off the coast of Click here Mexico. This was the strongest earthquake to be A2 1.4c and 1.5c Social and economic impacts of recorded globally in 2017, resulting in it being the tectonic hazards p15 pdf version Click here second strongest ever in Mexico. OCR AS Topic 2.5 Hazardous Earth 4b Range of impacts Key terms on people as a result of earthquake activity – Tectonic, tectonic hotspot, plate boundary, case studies convergent boundary, aftershock, magnitude, + 5b Strategies – case studies tsunami, vulnerability. p39 pdf version Click here Learning objectives A2 Topic 3.5 Hazardous Earth 4b There is a range -

The Protection of Human Rights in the Mexican

THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE MEXICAN REPUBLICANISM CARLOS ALBERTO AGUILAR BLANCAS1 Abstract: Democracy is not only a procedure of choice and citizen participation, but also a set of values that affirm freedom and citizen’s rights. The reform of 2011 rose to constitutional rank the defence, protection and promotion of human rights, representing an unprecedented historic breakthrough. With these reforms, Mexico seeks to consolidate its constitutional system adapting it to reality, increasing its cultural diversity, values and traditions that have been shaping the Mexican identity. The full knowledge of their rights produces a citizenship aware of them, which, even for Mexico, is a long-term task. KEYWORDS: State, Government, Mexican Constitutional Law, Human Rights, International Law, Sovereignty. Summary: I. INTRODUCTION; II. AN APPROACH TO THE RULE OF LAW IN MEXICO; II.1. General aspects of the rule of law; II.2. Rule of law in Mexico; III. SCOPE OF CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM IN THE FIELD OF HUMAN RIGHTS FROM 2011; III.1. Aspects of the reform in the field of human rights, III.2. Jurisdictional implications of the reform in the field of human rights; III.3. Realities and prospects of human rights in Mexico; IV. CONCLUSIONS; V. REFERENCES. I. INTRODUCTION The constitutional state is characterized by the defence of the fundamental rights of individuals, in contrast to the classic constitutionalism, which sought the political freedom of the citizens against the public abuse of power (SCHMITT, 1992: 138), i.e., in those days it was reflected that there was not a bourgeois rule of law, that there was no individual rights and the separation or division of powers was not established. -

Measuring Corruption in Mexico

MEASURING CORRUPTION IN MEXICO Jose I. Rodriguez-Sanchez, Ph.D. Postdoctoral Research Fellow in International Trade, Mexico Center December 2018 © 2018 by the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Jose I. Rodriguez-Sanchez, Ph.D. “Measuring Corruption in Mexico” Measuring Corruption in Mexico Introduction Corruption is a complex problem affecting all societies, and it has many different causes and consequences. Its consequences include negative impacts on economic growth and development, magnifying effects on poverty and inequality, and corrosive effects on legal systems and governance institutions. Corruption in the form of embezzlement or misappropriation of public funds, for example, diverts valuable economic resources that could be used on education, health care, infrastructure, or food security, while simultaneously eroding faith in the government. Calculating and measuring the impact of corruption and its tangible and intangible costs are essential to combating it. But before corruption can be measured, it must first be defined. Decision-makers have often resorted to defining corruption in a certain area or location by listing specific acts that they consider corrupt. Such definitions, however, are limited because they are context-specific and depend on how individual governments decide to approach the problem. -

Migration and Human Rights at Mexico's Southern Border

The Neglected Border: Migration and Human Rights at Mexico's Southern Border The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bahena Juarez, Jessica. 2019. The Neglected Border: Migration and Human Rights at Mexico's Southern Border. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004203 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA !"#$%#&'#()#*$+,''-$./&0,)/12$,2*$345,2$6/&")7$,)$.#8/(197$:14)"#02$;10*#0$ <#77/(,$;,"#2,$$ =$!"#7/7$/2$)"#$>/#'*$1?$@2)#02,)/12,'$6#',)/127$ ?10$)"#$A#&0##$1?$.,7)#0$1?$B/C#0,'$=0)7$/2$D8)#27/12$:)4*/#7$ $ 3,0E,0*$F2/E#07/)G$ .,G$HIJK$$ L1MG0/&")$HIJK$<#77/(,$;,"#2,$ =C7)0,()$ $ !"#$(15M'#8/12$1?$5/&0,2)$?'1N7$1E#0$.#8/(1O7$714)"#02$C10*#0$",7$(",2&#*$ ?10(#?4''G$/2$(12)#5M10,0G$#0,)/127P$!"/7$7)4*G$#8M'10#7$)"#$"/7)10/(,'$)0#2*7$1?$ L#2)0,'$=5#0/(,2$5/&0,)/12Q$)"#$(15M'#8/)G$1?$.#8/(197$714)"#02$C10*#0Q$,2*$0#,7127$ ?10$)"#$?,/'40#$1?$M01&0,57$/5M'#5#2)#*$)1$M01)#()$5/&0,2)79$0/&")7P$!"#$,0&45#2)$ M01M17#*$/2$)"/7$)"#7/7$/7$)",)$*#7M/)#$C#/2&$?0,5#*$/2$,$',2&4,&#$)",)$M0151)#7$ M01)#()/12Q$.#8/(,2$C10*#0$#2?10(#5#2)$M1'/(/#7$,2*$M0,()/(#7$1C7(40#$)"#$E/1'#2(#$12$ )"#$&0142*P$@)$?/2*7$)",)$M01&0,57$/5M'#5#2)#*$CG$)"#$.#8/(,2$&1E#025#2)$)1$M01)#()$ 5/&0,2)79$0/&")7$,2*$0#&4',)#$5/&0,)/12$?015$)"#$%10)"#02$!0/,2&'#$1?$L#2)0,'$=5#0/(,$ -

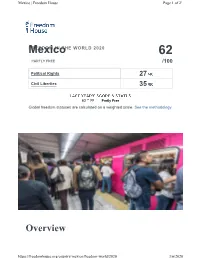

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Mexico | Freedom House Page 1 of 23 MexicoFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 62 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 27 Civil Liberties 35 63 Partly Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/mexico/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Mexico | Freedom House Page 2 of 23 Mexico has been an electoral democracy since 2000, and alternation in power between parties is routine at both the federal and state levels. However, the country suffers from severe rule of law deficits that limit full citizen enjoyment of political rights and civil liberties. Violence perpetrated by organized criminals, corruption among government officials, human rights abuses by both state and nonstate actors, and rampant impunity are among the most visible of Mexico’s many governance challenges. Key Developments in 2019 • President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who took office in 2018, maintained high approval ratings through much of the year, and his party consolidated its grasp on power in June’s gubernatorial and local elections. López Obrador’s polling position began to wane late in the year, as Mexico’s dire security situation affected voters’ views on his performance. • In March, the government created a new gendarmerie, the National Guard, which officially began operating in June after drawing from Army and Navy police forces. Rights advocates criticized the agency, warning that its creation deepened the militarization of public security. • The number of deaths attributed to organized crime remained at historic highs in 2019, though the rate of acceleration slowed. Massacres of police officers, alleged criminals, and civilians were well-publicized as the year progressed. -

Mexico-Systematic-Country-Diagnostic.Pdf

Public Disclosure Authorized Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Mexico Systematic Public Disclosure Authorized Country DiagnosticNovember 2018 Mexico Public Disclosure Authorized © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 21 20 19 18 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclu- sions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privi- leges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2018. Mexico - Systematic Country Diagnostic (English). Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. Translations—If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation. -

The Colonial Legacy and Human Rights in Mexico: Indigenous Rights and the Zapatista Movement by Alexander Karklins

_______________________________________HUMAN RIG H TS & HU MAN W ELFARE The Colonial Legacy and Human Rights in Mexico: Indigenous Rights and the Zapatista Movement By Alexander Karklins The current status of human rights in Latin America has been profoundly affected by the legacy of colonial institutions. Since the time of conquest, through colonialism, and after independence, the growth of the Latin American state has been challenged by the alternative discourse of indigenous rights. In Mexico, the dominance of mestizaje (or the quest for a single Mexican ethnic identity) in the formation of its modern state apparatus has left indigenous cultures out of the realm of political participation and exposed to human rights violations. With the Zapatista uprising of 1994-1996, the contradictions inherent in Mexico’s constitution were brought to the forefront and placed the discourse of indigenous rights squarely on the global human rights agenda. Mexico provides an interesting case in the evolution of indigenous rights discourse, considering the large number of indigenous groups within its borders, especially in Oaxaca and Chiapas. The Zapatista rebellion illustrates the ways in which indigenous claims have sought to challenge the state, as well as claims of universality in global human rights policies. It has, in many ways, forced the leaders of the Mexican State to take a hard look at its colonial past. From the period of conquest through Spain and Portugal’s colonial endeavors, there has been a constant struggle between indigenous groups and the state. Since independence, many Latin American governments have been dominated by remnants of the colonial project who modeled their new states distinctly after the states of their former colonial masters. -

Mexico: Joint Briefing Note on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in View of EU-Mexico Bilateral Human Rights Dialogue, Mexico City, April 2015

Mexico: joint briefing note on the situation of human rights defenders in view of EU-Mexico Bilateral Human Rights Dialogue, Mexico City, April 2015 The briefing note is complete with an annex of individual cases raised by Front Line Defenders in 2014 1. Facts and figures on Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) in Mexico In 2006 Felipe Calderón took up office as President of Mexico and under his administration a “war on drugs” was launched. Mexico experienced unprecedented levels of violence and insecurity throughout the country. The risk of defending human rights and practising journalism in Mexico increased at an alarming rate in the context of the “war on drugs”. Numerous cases of intimidation, legal harassment, death threats, enforced disappearances, killings and acts of aggressions have been documented against human rights defenders (HRDs) as a result of their human rights work. While the perpetrators are not identified in a great majority of cases, civil society has expressed concern that both state and non-state actors are reportedly responsible for such attacks. Regarding the involvement of state actors, such tendencies were observed either by their direct collusion in the aforementioned incidents, or by acquiescence. Although there was a change of administration in Mexico in December 2012, the public security strategies utilised by the current administration under Enrique Peña Nieto continue to arouse cause for concern and continue to place HRDs and journalists at risk. In recent months, Mexico has attracted international attention due to the enforced disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in the southern state of Guerrero at the end of September 2014. -

Human Security and Chronic Violence in Mexico New Perspectives and Proposals from Below

This book is the result of two years of participatory and Human Security action-oriented research into dynamics of insecurity and violence in modern-day Mexico. The wide-ranging Human Security and chapters in this collection offer a serious reflection of an innovative co-construction with residents from some of the most affected communities that resulted in diagno- Chronic Violence PUBLIC ses of local security challenges and their impacts on indi- POLITICS vidual and collective wellbeing. The book also goes on to in Mexico present a series of policy proposals that aim to curtail the New Perspectives and Proposals from Below reproduction of violence in its multiple manifestations. The methodological tools and original policy proposals Gema Kloppe-Santamaría • Alexandra Abello Colak presented here can help to enable a radical rethink of re- Editors sponses to the crisis of insecurity in Mexico and the wider Latin American region. Human Security and Chronic Violence Human Security and Chronic Violence in Mexico New Perspectives and Proposals from Below Human Security and Chronic Violence in Mexico New Perspectives and Proposals from Below Gema Kloppe-Santamaría • Alexandra Abello Colak Editors MEXICO 2019 This is a peer-reviewed scholarly research supported by the co-editor publisher. 364.20972 S4567 Human Security and Chronic Violence in Mexico: New Perspectives and Proposals from Below / edited by Gema Kloppe-Santamaría and Alexandra Abello Colak -- 1st edition -- Mexico : Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México : Miguel Ángel Porrúa, 2019. Electronic resource (299 p.) -- (Public Policies) ISBN 978-607-524-296-5 Violence -- Mexico. 2. Crime Prevention -- Mexico. 3. Public Security -- Mexico. 4. -

THE BOOK Women’S Forum Dubai

www.womens-forum.com Next editions WOmen’s FORUM ITALY THE BOOK Milan, 29-30 June 2015 WOmen’s FORUM GLOBAL MEETING Deauville, France, 14-15-16 October 2015 WOMEN’S FORUM BRAZIL G 14 N WOmen’s FORUM BRUSSELS I In 2016 WOmen’s FORUM JAPAN MEET WOmen’s FORUM MEXICO THE BOOK WOmen’s FORUM DUBAI BAL O L G Women’s Forum for the Economy and Society 59 boulevard Exelmans - 75016 Paris – France RUM Leading for a more +33 1 58 18 62 00 [email protected] equitable world community.womensforum.com FO S ' 15 16 17 October 2014 Follow the Women’s Forum on social media th MEN GLOBAL MEETING Leading for a more equitable world WO anniversary Deauville, France, 15-16-17 October 2014 Editorial The 2014 Women’s Forum Global Meeting, which marked the 10th anniversary of our flagship event in Deauville, built on the theme Leading for a more equitable world. With a broad sampling of topical content and powerful speakers, we took an in-depth look at the challenges women will face over the next decade, with an eye toward workable solutions. In her closing remarks, Véronique Morali, my predecessor as President of the Women’s Forum for the Economy and Society, congratulated speakers, participants and partners for their courage to confront obstacles to women’s empowerment as well as for their perseverance in the drive to overcome them. “We live in a world of paradox, because we need to be cheerful, even though we are very depressed every year by what happens,” Ms Morali said. -

(Re)Constructing Professional Journalistic Practice in Mexico

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 2596–2619 1932–8036/20190005 (Re)constructing Professional Journalistic Practice in Mexico: Verificado’s Marketing of Legitimacy, Collaboration, and Pop Culture in Fact-Checking the 2018 Elections NADIA I. MARTÍNEZ-CARRILLO Roanoke College, USA DANIEL J. TAMUL Virginia Tech, USA Although fact-checking websites for political news such as FactCheck.org, Politifact, and ProPublica are common in the United States, they are new in Mexico. Using textual analysis, this study examines the strategies used by Verificado 2018, a crowdsourced political fact-checking initiative generated during the largest election in Mexican history by news organizations, universities, and tech companies. Verificado 2018 emphasized legitimacy, collaboration, and critical humor to promote and engage users in fact- checking and viralizing reliable information. Keywords: Verificado, misinformation, Mexico, elections, fact-checking Presenting accurate depictions of news has always been central to journalism (see Schudson, 2011). However, modern journalists are trained to present competing statements as “equally viable truth claims” (Durham, 1998, p. 124). This practice can create a “flight from the truth” in service of objectivity and balance (Muñoz-Torres, 2012; Rosen, 1993, p. 4949). Although both strategies serve to legitimize news outlets by making them appear impartial (McChesney, 2004), fact-checking organizations operate within a separate institutional logic, necessitating journalists to judge the veracity of public statements (see Lowrey, 2017, for a review). Lowrey (2017) contends this violates traditional journalistic norms, eroding the legitimacy of fact-checking. With this context in mind, we examine the case of Verificado 2018—a temporary, collaborative, and decentralized fact-checking newsroom—and its communication strategy in the run-up to the 2018 Mexican campaign season. -

México 2017: El Gobierno En Desventaja Rumbo Al 2018

REVISTA DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA / VOLUMEN 38 / N° 2 / 2018 / 303-333 MEXICO 2017: INCUMBENT DISADVANTAGE AHEAD OF 2018 México 2017: El gobierno en desventaja rumbo al 2018 EDWIN ATILANO ROBLES Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE), Mexico ALLYSON LUCINDA BENTON Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE), Mexico ABSTRACT Weak economic performance, high inflation, and a devalued peso drew criticism of the incumbent Institutional Revolutionary Party’s (PRI) economic and fiscal policy choices, and kept President Enrique Peña Nieto’s approval ratings low. The incum- bent PRI thus entered the 2018 electoral season in a weak position, with reduced chances of defeating its main opposition candidate, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA). Keywords: economic performance, Mexican earthquake, public security, NAFTA, PRI, public opinion, Mexico RESUMEN El débil desempeño, la alta inflación y la devaluación del peso crearon un escenario de críti- cas hacia las decisiones económicas y fiscales del partido en el gobierno, el Partido Revolucio- nario Institucional (PRI), y de igual forma facilitaron que el presidente Enrique Peña Nieto tuviera una baja tasa de aprobación. El PRI inició el periodo electoral de 2018 en una posi- ción débil, lo cual redujo sus posibilidades de derrotar al principal candidato de oposición, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, del Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional (MORENA). Palabras clave: desempeño económico, terremoto mexicano, seguridad pública, TLCAN, PRI, opinion pública, México EDWIN ATILANO ROBLES • ALLYSON LUCINDA BENTON I. INTRODUCTION Ongoing weak economic growth, important social concerns, and deteriorating security conditions during 2017 put the incumbent Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Institucional or PRI) at a disadvantage ahead of the 2018 presidential race.