Measuring Corruption in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chiapas Earthquake, Mexico 2017

GEOFILE Extension 781 The Chiapas earthquake, Mexico 2017 By Philippa Simmons Synopsis Links This Geofile will explore the causes and impacts of Exam board Link to specification the Chiapas earthquake that occurred in Mexico in AQA September 2017, as well as the responses to it. Mexico AS Component 1 Physical Geography 3.3.1.4 is situated where the Cocos plate converges with the Seismic hazards p18 pdf version North American plate – one of the most tectonically Click here active regions in the world, with up to 40 earthquakes A2 Component 1 Physical Geography 3.1.5.4 a day. The state of Chiapas is located along the Seismic hazards p15 pdf version Click here southern shore of Mexico and borders Guatemala, it is in a subduction zone and is at risk of strong Edexcel AS 1.4c and 1.5c Social and economic impacts of earthquakes. At 23.49 local time on 7 September 2017 tectonic hazards p18 pdf version an earthquake of magnitude 8.2 struck off the coast of Click here Mexico. This was the strongest earthquake to be A2 1.4c and 1.5c Social and economic impacts of recorded globally in 2017, resulting in it being the tectonic hazards p15 pdf version Click here second strongest ever in Mexico. OCR AS Topic 2.5 Hazardous Earth 4b Range of impacts Key terms on people as a result of earthquake activity – Tectonic, tectonic hotspot, plate boundary, case studies convergent boundary, aftershock, magnitude, + 5b Strategies – case studies tsunami, vulnerability. p39 pdf version Click here Learning objectives A2 Topic 3.5 Hazardous Earth 4b There is a range -

Understanding the Problems and Obstacles of Corruption in Mexico

ISSUE BRIEF 09.13.18 Understanding the Problems and Obstacles of Corruption in Mexico Jose I. Rodriguez-Sanchez, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Research Fellow in International Trade, Mexico Center Corruption is an ancient and complex and public issue. Some focus on it in the phenomenon. It has been present in public sector; others examine it in the private various forms since the earliest ancient sector. Of the various approaches to defining Mesopotamian civilizations, when abuses corruption, the most controversial approach from public officials for personal gain were is that of the so-called moralists. From the recorded.1 Discussions on political corruption moralist perspective, an act of corruption also appeared in the writings of Greek should not be defined as wrong or illegal, philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle.2 as it is contextual and depends upon the For centuries now, philosophers, sociologists, norms of the society in which it occurs. This political scientists, and historians have perspective, though important, has been analyzed the concept of corruption, usually largely avoided by modern social scientists in in the context of bribery. More recently, in favor of an institutional approach to defining the face of globalization and political and corruption, which is based on legal norms that financial integration, the study of corruption resolve conflicts between different sectors has broadened to include many different of a society that are affected by corruption. manifestations. Even so, there is not a single This institutional approach may better help in definition of corruption accepted by scholars measuring and combating corruption. and institutions working on this issue. -

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations May 21, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45733 SUMMARY R45733 Combating Corruption in Latin America May 21, 2019 Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from June S. Beittel, office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency Coordinator International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of Analyst in Latin American respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several Affairs analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize Peter J. Meyer citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative Specialist in Latin investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater American Affairs affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean Clare Ribando Seelke countries. Specialist in Latin American Affairs Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter Maureen Taft-Morales discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of Specialist in Latin official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized American Affairs crime and criminal impunity. -

The Civil Society-Driven Anti-Corruption Push in Mexico During the Enrique

MEXICO CASE STUDY Rise and Fall: Mexican Civil Society’s Anti-Corruption Push in the Peña Nieto Years Roberto Simon AS/COA Anti Corruption Working Group Mexican Civil Society’s Anti-Corruption Push in the Peña Nieto Years Rise and Fall: Mexican Civil Society’s Anti-Corruption Push in the Peña Nieto Years Mexico City — “Saving Mexico” declared the cover of Time magazine, alongside a portrait of President Enrique Peña Nieto gazing confidently toward the future.1 Elected in 2012, Peña Nieto had been in power for only 15 months, yet already his bold reform agenda — dubbed the “Pacto por Mexico” (Pact for Mexico) — had made him a darling of global investors. Time noted that the president — “assisted by a group of young technocrats (including) Finance Minister Luis Videgaray and Pemex chief Emilio Lozoya” — was making history by breaking Mexico’s eight-decade state monopoly over the energy industry. “And the oil reform might not even be Peña Nieto’s most important victory,” the magazine said. There was “evidence” that Peña Nieto was about to “challenge Mexico’s entrenched powers.” While most investors focused on the deep regulatory changes under way, leading Mexican civil society organizations were looking at another critical promise in the Pacto por Mexico: fighting endemic corruption. “For centuries, corruption has been one of the central elements of the Mexican state (and) a constant in shaping the political system,” said Jorge Buendía, a prominent pollster and political analyst. A powerful governor from the 1960s to the 1980s allegedly once said that in Mexico “a poor politician is a poor politician.”2 And by the time Peña Nieto came to power, most in the country believed that things hadn’t really changed. -

The Netherlands: Phase 2

DIRECTORATE FOR FINANCIAL AND ENTERPRISE AFFAIRS THE NETHERLANDS: PHASE 2 REPORT ON THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON COMBATING BRIBERY OF FOREIGN PUBLIC OFFICIALS IN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS AND THE 1997 RECOMMENDATION ON COMBATING BRIBERY IN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS This report was approved and adopted by the Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions on 15 June 2006. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................5 A. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................6 1. On-Site Visit ....................................................................................................................6 2. General Observations.......................................................................................................7 a. Economic system.............................................................................................................7 b. Political and legal systems...............................................................................................9 c. Implementation of the Convention and Revised Recommendation...............................10 d. Cases involving the bribery of foreign public officials .................................................11 (i) Investigations, prosecutions and convictions...........................................................11 (ii) Response to the Report of the -

Key 2017 Developments in Latin American Anti-Corruption Enforcement

March 15, 2018 KEY 2017 DEVELOPMENTS IN LATIN AMERICAN ANTI-CORRUPTION ENFORCEMENT To Our Clients and Friends: In 2017, several Latin American countries stepped up enforcement and legislative efforts to address corruption in the region. Enforcement activity regarding alleged bribery schemes involving construction conglomerate Odebrecht rippled across Latin America's business and political environments during the year, with allegations stemming from Brazil's ongoing Operation Car Wash investigation leading to prosecutions in neighboring countries. Simultaneously, governments in Latin America have made efforts to strengthen legislative regimes to combat corruption, including expanding liability provisions targeting foreign companies and private individuals. This update focuses on five Latin American countries (Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Peru) that have ramped up anti-corruption enforcement or passed legislation expanding anti-corruption legal regimes.[1] New laws in the region, coupled with potentially renewed prosecutorial vigor to enforce them, make it imperative for companies operating in Latin America to have robust compliance programs, as well as vigilance regarding enforcement trends impacting their industries. 1. Mexico Notable Enforcement Actions and Investigations In 2017, Petróleos Mexicanos ("Pemex") disclosed that Mexico's Ministry of the Public Function (SFP) initiated eight administrative sanctions proceedings in connection with contract irregularities involving Odebrecht affiliates.[2] The inquiries stem from a 2016 Odebrecht deferred prosecution agreement ("DPA") with the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ").[3] According to the DPA, Odebrecht made corrupt payments totaling $10.5 million USD to Mexican government officials between 2010 and 2014 to secure public contracts.[4] In September 2017, Mexico's SFP released a statement noting the agency had identified $119 million pesos (approx. -

The Historical Consequences of Institutionalised

THE HISTORICAL CONSEQUENCES OF INSTITUTIONALISED CORRUPTION IN MODERN MEXICO by Michael Malkemus, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Political Science December 2014 Committee Members: Omar Sanchez-Sibony, Chair Edward Mihalkanin Paul Hart COPYRIGHT by Michael Malkemus 2014 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Michael Malkemus, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is a culmination of many years of passionate and exciting study of México. Its culture, politics, and people have long fascinated me. Therefore, first and foremost, the people of México must be warmly acknowledged. Secondly, I would like to extend gratitude to all of my professors and mentors that have introduced and taught me vital concepts relating to the political culture of México and Latin America. Finally, this would have been impossible without my parents and their unwavering support. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. -

Turning the Tide on Dirty Money Why the World’S Democracies Need a Global Kleptocracy Initiative

GETTY IMAGES Turning the Tide on Dirty Money Why the World’s Democracies Need a Global Kleptocracy Initiative By Trevor Sutton and Ben Judah February 2021 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Preface 3 Introduction and summary 6 How dirty money went global and why efforts to stop it have failed 10 Why illicit finance and kleptocracy are a threat to global democracy and should be a foreign policy priority 13 The case for optimism: Why democracies have a structural advantage against kleptocracy 18 How to harden democratic defenses against kleptocracy: Key principles and areas for improvement 21 Recommendations 28 Conclusion 29 Corruption and kleptocracy: Key definitions and concepts 31 About the authors and acknowledgments 32 Endnotes Preface Transparency and honest government are the lifeblood of democracy. Trust in democratic institutions depends on the integrity of public servants, who are expected to put the common good before their own interests and faithfully observe the law. When officials violate that duty, democracy is at risk. No country is immune to corruption. As representatives of three important democratic societies—the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom—we recognize that corruption is an affront to our shared values, one that threatens the resiliency and cohesion of democratic governments around the globe and undermines the relationship between the state and its citizens. For that reason, we welcome the central recommendation of this report that the world’s democracies should work together to increase transparency in the global economy and limit the pernicious influence of corruption, kleptocracy, and illicit finance on democratic institutions. -

Mexico's Anti-Corruption Spring

CHAPTER 1: CORRUPTION What are the mechanisms recently implemented in Mexico to reduce corruption and what Qis still to be done? POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS • Provide the special anti-corruption pros- ecutor with autonomy from government and other sources of potential conflict of interest. • Creating new laws alone will not reduce the problem. It is about implementing Aand setting an example. • Do not measure anti-corruption success by simple metrics of prosecution, instead rely on financial measures such as “gov- ernment corruption savings.” Mexico’s Anti- Corruption Spring BY MAX KAISER AND VIRIDIANA RÍOS exico’s policy priorities have shifted greatly during the last cou- ple of years, moving from an agenda focused mostly on reduc- Ming drug-related homicides to one that places a war against corruption as a requirement for successfully combatting drug trafficking organizations and their violence. This shift is significant on many fronts. The war against drug-related vio- lence was a war of the government against criminal organizations, a war to try to regain control over the impunity that reigned in territories where drug trafficking operations were conducted. The war against corruption is a war of its citizens against corruption rackets, a war against the illegal arrangements for private gain that pervade business, government, me- dia, and many other sectors of Mexican society, and that have allowed impunity to become systemic. Most critically, the definition of success has changed in nature, moving on from the targeted goal of reducing activities of organized crime to the more general goal of implanting the rule of law. In this chapter, we provide the reader with an up-to-date recounting of Mexico’s most recent efforts to promote the implementation of the rule of law in public affairs, namely the struggle to create a complete legal framework for prosecuting corruption cases. -

Corruption Risks in Sri Lanka

CORRUPTION RISKS IN SRI LANKA The overarching power and influence of the executive is weakening the national integrity system of Sri Lanka. KEY FINDINGS Erosion of checks and balances KEY FACTS: CORRUPTION The centralisation of power on the executive has eroded the constitutional checks and balances, leading to abuse of power PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2013 and widespread misappropriation of funds. The supremacy of the legislature as the mandate of the people has been challenged RANK: SCORE: along with the independence of the judicial system. 91/177 37/100 Politicisation of the public sector The independence of the public sector suffers from political What does this mean? influence. Although the Public Service Commission oversees the The Corruption Perceptions Index measures the appointments, promotions, transfers, discipline and dismissals of perceived levels of public sector corruption, scoring public officers, the commission itself is appointed by the from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). A score president. of less than 50 indicates a serious corruption problem. Gaps in the anti-corruption mechanism Sri Lanka’s Bribery Act of 1994 is yet to undergo any revision or update. The current act does not include private and civil society sectors and does not conform to the provisions of the United Nations Convention against Corruption. Nepal 6% 22% 72% Pakistan 8% 19% 72% Percentage (%) of people in South Asian countries on how the level of corruption in India 7% 23% 70% their respective country has changed over the previous two years. South Asia 14% 21% 66% Countries are listed according to the percentage Sri Lanka 18% 19% 64% of respondents who felt corruption had increased. -

The Missing Reform: Strengthening Rule of Law in Mexico

The Missing Reform: Strengthening the Rule of Law in Mexico EDITED BY VIRIDIANA RÍOS AND DUNCAN WOOD The Missing Reform: Strengthening the Rule of Law in Mexico EDITED BY VIRIDIANA RÍOS AND DUNCAN WOOD Producing a book like this is always a team effort and, in addition to the individual chapter authors, we would especially like to thank the Mexico Institute and Wilson Center team who gave so many hours to edit, design, and produce this book. In particular, we would like to mention Angela Robertson, Kathy Butterfield, and Lucy Conger for their dedication as well as their professional skill. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars ISBN 978-1-938027-76-5 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION / 1 SECTION 1 / 18 Corruption / 18 The Justice System / 44 Democracy and Rule of Law / 78 Business Community / 102 Public Opinion / 124 Media and the Press / 152 SECTION 2 / 182 Education / 182 Transparency / 188 Competition / 196 Crime Prevention / 202 Civil Society / 208 Congress and Political Parties / 214 Energy / 224 Land Tenure / 232 Anticorruption Legislation / 240 Police Forces / 246 Acknowledgements This book collects the intelligence, commitment, and support of many. It comprises the research, ideas and hopes of one of the most talented pools of Mexican professionals who day-to-day, in different spheres, work to strengthen rule of law in their own country. Collaborating with them has been among the highest honors of my career. I cannot thank them enough for believing in this project. -

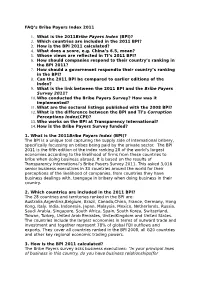

FAQ's Bribe Payers Index 2011

FAQ’s Bribe Payers Index 2011 1. What is the 2011Bribe Payers Index (BPI)? 2. Which countries are included in the 2011 BPI? 3. How is the BPI 2011 calculated? 4. What does a score, e.g. China’s 6.5, mean? 5. Whose views are reflected in TI’s 2011 BPI? 6. How should companies respond to their country’s ranking in the BPI 2011? 7. How should a government respondto their country’s ranking in the BPI? 8. Can the 2011 BPI be compared to earlier editions of the index? 9. What is the link between the 2011 BPI and the Bribe Payers Survey 2011? 10. Who conducted the Bribe Payers Survey? How was it implemented? 11. What are the sectoral listings published with the 2008 BPI? 12. What is the difference between the BPI and TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index(CPI)? 13. Who works on the BPI at Transparency International? 14. How is the Bribe Payers Survey funded? 1. What is the 2011Bribe Payers Index (BPI)? The BPI is a unique tool capturing the supply side of international bribery, specifically focussing on bribes being paid by the private sector. The BPI 2011 is the fifth edition of the index ranking 28 of the world’s largest economies according to the likelihood of firms from these countries to bribe when doing business abroad. It is based on the results of Transparency International’s Bribe Payers Survey 2011. This asked 3,016 senior business executives in 30 countries around the world for their perceptions of the likelihood of companies, from countries they have business dealings with, toengage in bribery when doing business in their country.