Open Huot-Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resettlement Planning Document

Resettlement Planning Document Short Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 40914 September 2006 CAM: CPTL Power Transmission Project Prepared by CPTL Power Transmission Lines Co. Ltd. The short resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 June 2006) Currency Unit – $ KR 1.00 = $0.0002 $1.00 = KR 4,163 ABBREVIATIONS ADB = Asian Development Bank AP = Affected person CPTL = (Cambodia) Power Transmission Lines Co. Ltd. FY = Fiscal Year GMS = Greater Mekong Subregion IEE = Initial Environment Evaluation KR = Riel NR5 = National Road Five NR6 = National Road six OMF2/BP = ADB Operational Manual Bank Policy OMF2/OP = ADB Operational Manual Operating Procedures OSPF = Office of the Special Project Facilitator PEA = Provincial Electricity Authority PSCM = Private Sector Credit Committee PSOD = Private Sector Operations Department ROW = Rights of Way RP = Resettlement Plan SRP = Short Resettlement Plan iii WEIGHTS AND MEASURES GWh – 1,000,000 kilowatt-hours Ha – hectare Km – kilometer kV – kilovolt kWh – kilowatt-hour (the energy of 1 kW of capacity operating for 1 hour) m – meter m2 – square meter mm – millimeter MVA – megavolt-ampere MW – megawatt (1,000,000 watts) GLOSSARY Affected - means any person or persons, household, firm, private or public person (AP) institution that, on account of changes resulting from the Project, will have its (i) standard of living adversely affected; (ii) right, title or interest in any house, land (including residential, commercial, agricultural, forest, salt mining and/or grazing land), water resources or any other moveable or fixed assets acquired, possessed, restricted or otherwise adversely affected, in full or in part, permanently or temporarily; and/or (iii) business, occupation, place of work or residence or habitat adversely affected, with or without displacement. -

Quarterly Report #21 Helping Address Rural Vulnerabilities and Ecosystem Stability (Harvest) Program

Prepared by Fintrac Inc. QUARTERLY REPORT #21 HELPING ADDRESS RURAL VULNERABILITIES AND ECOSYSTEM STABILITY (HARVEST) PROGRAM January – March 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Fintrac Inc. under contract # AID-442-C-11-00001 with USAID/Cambodia. HARVEST ANNUAL REPORT #1, DECEMBER 2010 – SEPTEMBER 2011 1 Fintrac Inc. www.fintrac.com [email protected] US Virgin Islands 3077 Kronprindsens Gade 72 St. Thomas, USVI 00802 Tel: (340) 776-7600 Fax: (340) 776-7601 Washington, D.C. 1400 16th St. NW, Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20036 USA Tel: (202) 462-8475 Fax: (202) 462-8478 Cambodia HARVEST No. 34 Street 310 Sangkat Beong Keng Kang 1 Khan Chamkamorn, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tel: 855 (0) 23 996 419 Fax: 855 (0) 23 996 418 QUARTERLY REPORT #21 HELPING ADDRESS RURAL VULNERABILITIES AND ECOSYSTEM STABILITY (HARVEST) PROGRAM January – March 2016 The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Program Description ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Geographic Focus ........................................................................................................................................... -

Type of the Paper (Article

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 8 November 2016 doi:10.20944/preprints201611.0046.v1 Article An Analysis of Technical Efficiency for Household's Rice Production in Cambodia: A Case Study of Three Districts in Battambang Province Sokvibol Kea 1,2,*, Hua Li 1,* and Linvolak Pich 3 1 College of Economics and Management (CEM), Northwest A&F University, 712100 Shaanxi, China 2 Faculty of Sociology & Community Development, University of Battambang, 053 Battambang, Cambodia 3 College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering (CWRAE), Northwest A&F University, 712100 Shaanxi, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (H.L.); Tel.: +855-96-986-6668 (S.K.); +86-133-6393-6398 (H.L.) Abstract: The aims of this study are to measure the technical efficiency (TE) of Cambodian household’s rice production and trying to determine its main influencing factors using the stochastic frontier production function. The study utilized primary data collected from 301 rice farmers in three selected districts of Battambang by structured questionnaires. The empirical results indicated the level of household rice output varied according to differences in the efficiency of production processes. The mean TE is 0.34 which means that famers produce 34% of rice at best practice at the current level of production inputs and technology, indicates that rice output has the potential of being increased further by 66% at the same level of inputs if farmers had been technically efficient. Furthermore, between 2013-2015 TE of household’s rice production recorded -14.3% decline rate due to highly affected of drought during dry season of 2015. -

Rural Roads Improvement Project II: Economic and Financial Analysis

Rural Roads Improvement Project II (RRP CAM 42334) ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS 1. The economic internal rate of return (EIRR) for the project is calculated as the difference between the capital and road user costs with and without the project. Calculations are made for 24 years starting in 2013. Road and jetty improvements are assumed to be completed in 2018, giving a benefit period of 20 years. No benefits are included for sections of roads completed before the end of the overall construction period. 2. The approach to the financial analysis follows the Guidelines for the Financial Analysis of Projects of the Asian Development Bank (ADB). 1 Given that the project is not revenue generating, the analysis focuses on the executing agency’s financial capacity to meet the recurrent costs of operating and maintaining the developed facilities in a sustainable manner. The overall financial position of the executing agency is appraised to ensure the financial capacity to cover recurrent project costs. A. Prices 3. Costs and benefits are calculated using economic costs based on border prices for traded goods and services, and domestic market prices net of taxes and subsidies for nontraded items. The prices are for mid-2013 using dollars. The net of tax economic cost of regular gasoline is calculated at $0.88/liter and diesel at $0.96/liter based on border prices. Lubricant costs are estimated at about $3.00/liter for motorcycles and $5.00/liter for 4-wheel drives. Passenger time values are likely to increase in real terms, in step with increasing per capita income; an allowance is made to reflect this. -

RDJR0658 Paddy Market

Appendix Appendix 1: The selected 3 areas for feasibility study A-1 Mongkol Borei, Banteay Meanchey + Babel & Thma Koul, Battambang Koy Maeng Ruessei Kraok # N #Y# Feasibility Study Area Bat Trang Mongkol Borei Mongkol Borei, Bavel and Thma Koul Districts # # # Ta Lam # Rohat Tuek Srah Reang # Ou Prasat # # Chamnaom Kouk Ballangk # # Sambuor P# hnum Touch Soea # Boeng Pring # # Prey Khpo#s Lvea Chrouy Sdau # Thmar Koul Kouk Khmum Ta Meun Ampil Pram Daeum Khnach Romeas # # # # # # # Bansay TraenY#g# Bavel Y# Bavel Rung Chrey Ta Pung BANTEAY MEAN CHEY Kdol Ta Hae#n (/5 Ru ess ei K rao k #Ko y Ma en g # Bat Tr an g #Mong kol Borei Ta La m #Ban te ay #YNea ng # Anlong Run # Sra h Re a ng Roha t Tu e k # Ou Ta Ki # Kou k Ba l ang k #Ou Pras a t # Sa m bu o r Ch am n #aom # BANTEAY ME AN CHEY Phnu m To uc h # #So e a # Bo en g Pri ng Lve a Pre y Kh p#o s # # Chro u y Sd au BAT TAMB ANG # Kou k Kh mum Thma K ou l Kh nac h R om e as Ta Meu n Ampil Pra m Daeu m Bav e l Bans a y Tr aen g # Ru ng Ch#re y ## Ta Pu n g # Y#B#av el # Y# Chrey# # Kd ol T a Hae n BATTAMBANG An lon g Ru #n # Ou Ta K i # Chre y Provincial road 8 0 8 16 Kilometers National road Railway A-2 Moung Ruesssei, Battambang + Bakan, Pursat Feasibility Study Area N Moung Ruessei and Bakan Districts Prey Touch # Thipakdei # # Kakaoh 5 Ta Loas /( # Moung Ruessei # Chrey Moung Ruessei #Y# # Kear # Robas Mongkol Prey Svay # Ruessei Krang Me Tuek # # Svay Doun Kaev # # #Ou Ta Paong Preaek Chik Boeng Khnar # # Bakan Sampov Lun Boeng Bat Kandaol Trapeang Chong #Phnum Proek BATTAM BANG -

Battambang(PDF:320KB)

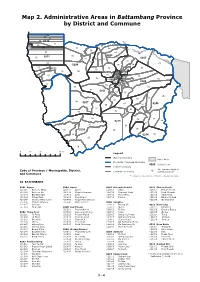

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 06 05 04 03 0210 01 02 07 04 03 04 06 03 01 02 06 0211 05 0202 05 01 0205 01 10 09 08 02 01 02 07 0204 05 04 05 03 03 0212 05 03 04 06 06 06 04 05 02 03 04 02 02 0901 03 04 08 01 07 0203 10 05 02 0208 08 09 01 06 10 08 06 01 04 07 0201 03 07 02 05 08 06 01 04 0207 01 0206 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 06 03 09 03 0213 04 02 07 04 01 05 0209 06 04 0214 02 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water Area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0211 Phnom Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 -

Eliminating Exploitative Child Labor Through Education and Livelihoods

Independent Final Evaluation Cambodians EXCEL Project Eliminating eXploitative Child Labor Through Education and Livelihoods World Vision Inc. December 2012–December 2016 Evaluator: Deborah Orsini, Management Systems International Under contract to: United States Department of Labor Cooperative Agreement IL-23070-K Management Systems International | msiworldwide.com 200 South 12th Street | Arlington, VA, USA | +1 703 979 7100 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................... ii ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ v Evaluation Findings ............................................................................................................................................ vi Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................. xi I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION................................................................................................................................... 1 A. Project Context .............................................................................................................................................. -

Comparison of Cambodian Rice Production Technical 2 Efficiency At

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 29 September 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201709.0161.v1 1 Article 2 Comparison of Cambodian Rice Production Technical 3 Efficiency at National and Household Level 4 Sokvibol Kea 1,2,*, Hua Li 1,* and Linvolak Pich 3 5 1 College of Economics and Management (CEM), Northwest A&F University, 712100 Shaanxi, China 6 2 Faculty of Sociology & Community Development, University of Battambang, 053 Battambang, Cambodia 7 3 College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering (CWRAE), Northwest A&F University, 712100 8 Shaanxi, China; [email protected] 9 * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (H.L.); Tel.: +855-96-986-6668 (S.K.); 10 +86-133-6393-6398 (H.L.) 11 Abstract: Rice is the most important food crop in Cambodia and its production is the most 12 organized food production system in the country. The main objective of this study is to measure 13 technical efficiency (TE) of Cambodian rice production and also trying to identify core influencing 14 factors of rice TE at both national and household level, for explaining the possibilities of increasing 15 productivity and profitability of rice, by using translog production function through Stochastic 16 Frontier Analysis (SFA) model. Four-years dataset (2012-2015) generated from the government 17 documents was utilized for the national analysis, while at household-level, the primary three-years 18 data (2013-2015) collected from 301 rice farmers in three selected districts of Battambang province 19 by structured questionnaires was applied. The results indicate that level of rice output varied 20 according to the different level of capital investment in agricultural machineries, total actual 21 harvested area, and technically fertilizers application within provinces, while level of household 22 rice output varied according to the differences in efficiency of production processes, techniques, 23 total annual harvested land, and technically application of fertilizers and pesticides of farmers. -

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 06 05 04 03 0210 01 02 07 04 03 04 06 03 01 02 06 05 0202 05 0211 01 0205 01 10 09 08 02 01 02 07 0204 05 04 05 03 03 0212 05 03 04 06 06 06 04 05 02 03 04 02 02 0901 03 04 08 01 07 0203 10 05 02 0208 08 09 01 06 10 08 06 01 04 07 0201 03 07 02 05 08 06 01 04 0207 01 0206 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 06 03 09 03 0213 04 02 07 04 01 05 0209 06 04 0214 02 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water Area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0211 Phnom Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 -

2019-Extension-Request-Cambodia

KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA Nation Religion King The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction Request for an extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of anti-personnel mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION The Kingdom of Cambodia signed the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (APMBC) on 3 December 1997 and ratified it on 28 July 1999, becoming a State Party on 1 January 2000. Due to the magnitude and nature of the AP mine problem in the country, Cambodia needed to extend its AP mine clearance deadline, with the APMBC setting a new deadline for 1 January 2020. The period of the first extension request is from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2019. For this document, figures are from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2018 (as retrieved on 31 January 2019) unless otherwise specified. Overview of the achievements since the first extension request was granted Cambodia exceeded the targets outlined in the first extension request, releasing 577,171,932 square meters of AP mine affected land (target: 470,048,519 square meters or 123 per cent). 946 villages can be declared as known AP mine-free. The table below shows the annual clearance achievements of the entire sector and the percentages achieved against the annual target. Table. Annual clearance targets and achievements (2010 to 2018) Year Annual target Achieved (total) % achieved Achieved % achieved Achieved Achieved sqm (total) against (APM) sqm (APM) -

Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 2014-2016 TECHNICAL REPORT (CAMBODIA)

Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 2014-2016 TECHNICAL REPORT (CAMBODIA) By Center for Advanced Study for Asian Barometer Survey Center for East Asia Democratic Studies National Taiwan University January, 2016 Contact Information Center for Advanced Study #160, street 156, Teuk Laak 2, Tuol Kork, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tel: 855 23 884 564; Mobile: 855 16 813 511 Fax: 855 23 884 564 Email:[email protected]; [email protected] Asian Barometer Survey No.1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei 10617, Taiwan Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, College of Social Sciences National Taiwan University Tel: 886-2-3366-8456 Fax: 886-2-2365-7179 Email: [email protected] 1. BASIC INFORMATION 1.1 LOCATION The Asian Barometer 2015 Survey covered the entire 25 provinces of Cambodia 1.2 POPULATION The population of Cambodia in 2008 was 13,941,000, with estimation at 15,408,270 as of 2014.1 1.3 GOVERNMENT The politics of Cambodia takes place in a frame work of a constitutional monarchy, where by the Prime Minister is the head of government and a Monarch is head of state. The kingdom formally operates according to the nation’s constitution (enacted in 1993) in a framework of a parliamentary, representative democracy. Executive power is exercised by the Prime Minister Hun Sen. Legislative power is vested in the two chambers of parliament, the National Assembly and the Senate. The Prime Minister of Cambodia is a representative from the ruling party of the National Assembly. He or she is appointed by the King on the recommendation of the President and Vice Presidents of the National Assembly. -

Cities and Provinces of Cambodia Юšijʼn-Ū˝О₣ Аĕ Ūįйŭď

CITIES AND PROVINCES OF CAMBODIA (English and Khmer Languages) ЮŠijʼn-Ū˝₣О аĕ ŪĮйŬď₧şŪ˝˝ņįОď (ļ⅜Β₣сЮÐų₤ ĕЊ₣ļ⅜ЯŠŊũ) English language: page 2 to 116 (unaltered transliteration) Khmer language: page 117 to 218 Source: http://www.cambodia.gov.kh Compiled by: Bunleng CHEUNG (UNAKRT-ECCC Translator) As of June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Province Page BANTEAY MEANCHEY ........................................................................... 4 BATTAMBANG ......................................................................................... 9 KAMPONG CHAM .................................................................................. 15 KAMPONG CHHNANG........................................................................... 27 KAMPONG SPEU..................................................................................... 32 KAMPONG THOM................................................................................... 40 KAMPOT .................................................................................................. 45 KANDAL .................................................................................................. 50 KOH KONG .............................................................................................. 59 KRATIE .................................................................................................... 61 KRONG KEP............................................................................................. 64 KRONG PAILIN ......................................................................................