Mamluk Studies Review Vol. X, No. 2 (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qt4nd9t5tt.Pdf

UC Irvine FlashPoints Title Moses and Multiculturalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nd9t5tt ISBN 978-0-520-26254-6 Author Johnson, Barbara Publication Date 2010 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Moses and Multiculturalism UCP_Johnson_Moses-ToPress.indd 1 12/1/09 10:10 AM FlashPoints The series solicits books that consider literature beyond strictly national and dis- ciplinary frameworks, distinguished both by their historical grounding and their theoretical and conceptual strength. We seek studies that engage theory without losing touch with history, and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints will aim for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history, and in how such formations func- tion critically and politically in the present. Available online at http://repositories .cdlib.org/ucpress s eries editors Judith Butler, Edward Dimendberg, Catherine Gallagher, Susan Gillman Richard Terdiman, Chair 1. On Pain of Speech: Fantasies of the First Order and the Literary Rant, by Dina Al-Kassim 2. Moses and Multiculturalism, by Barbara Johnson UCP_Johnson_Moses-ToPress.indd 2 12/1/09 10:10 AM Moses and Multiculturalism Barbara Johnson Foreword by Barbara Rietveld UN IVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London UCP_Johnson_Moses-ToPress.indd 3 12/1/09 10:10 AM University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. -

Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1

FAIRFIELD COUNTY CEMETERIES VOLUME II (Church Cemeteries in the Eastern Section of the County) Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church This book covers information on graves found in church cemeteries located in the eastern section of Fairfield County, South Carolina as of January 1, 2008. It also includes information on graves that were not found in this survey. Information on these unfound graves is from an earlier survey or from obituaries. These unfound graves are noted with the source of the information. Jonathan E. Davis July 1, 2008 Map iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1 Bethesda Methodist Church Cemetery 26 Centerville Cemetery 34 Concord Presbyterian Church Cemetery 43 Longtown Baptist Church Cemetery 62 Longtown Presbyterian Church Cemetery 65 Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church Cemetery 73 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – New 86 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 91 New Buffalo Cemetery 92 Old Fellowship Presbyterian Church Cemetery 93 Pine Grove Cemetery 95 Ruff Chapel Cemetery 97 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – New 99 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 102 St. Stephens Episcopal Church Cemetery 112 White Oak A. R. P. Church Cemetery 119 Index 125 ii iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery This cemetery is located on Highway 34 about 1 mile west of Ridgeway. Albert, Charlie Anderson, Joseph R. November 27, 1911 – October 25, 1977 1912 – 1966 Albert, Jessie L. Anderson, Margaret E. December 19, 1914 – June 29, 1986 September 22, 1887 – September 16, 1979 Albert, Liza Mae Arndt, Frances C. December 17, 1913 – October 22, 1999 June 16, 1922 – May 27, 2003 Albert, Lois Smith Arndt, Robert D., Sr. -

Egyptian Literature

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Egyptian Literature This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Egyptian Literature Release Date: March 8, 2009 [Ebook 28282] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EGYPTIAN LITERATURE*** Egyptian Literature Comprising Egyptian Tales, Hymns, Litanies, Invocations, The Book Of The Dead, And Cuneiform Writings Edited And With A Special Introduction By Epiphanius Wilson, A.M. New York And London The Co-Operative Publication Society Copyright, 1901 The Colonial Press Contents Special Introduction. 2 The Book Of The Dead . 7 A Hymn To The Setting Sun . 7 Hymn And Litany To Osiris . 8 Litany . 9 Hymn To R ....................... 11 Hymn To The Setting Sun . 15 Hymn To The Setting Sun . 19 The Chapter Of The Chaplet Of Victory . 20 The Chapter Of The Victory Over Enemies. 22 The Chapter Of Giving A Mouth To The Overseer . 24 The Chapter Of Giving A Mouth To Osiris Ani . 24 Opening The Mouth Of Osiris . 25 The Chapter Of Bringing Charms To Osiris . 26 The Chapter Of Memory . 26 The Chapter Of Giving A Heart To Osiris . 27 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 28 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 29 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 30 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 30 The Heart Of Carnelian . 31 Preserving The Heart . 31 Preserving The Heart . -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

I) If\L /-,7\ .L Ii Lo N\ C, ' II Ii Abstract Approved: 1'

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Asaad AI-Saleh for the Master of Arts Degree In English presented on _------'I'--'I--'J:..=u:o...1VL.c2=0"--'0"-=S'------ _ Title: Mustafa Sadiq al-Rafii: A Non-recognized Voice in the Chorus ofthe Arabic Literary Revival i) If\l /-,7\ .L Ii lo n\ C, ' II Ii Abstract Approved: 1'. C". C ,\,,: 41-------<..<.LI-hY,-""lA""""","""I,--ft-'t _ '" I) Abstract Mustafa Sadiq al-Rafii, a modem Egyptian writer with classical style, is not studied by scholars of Arabic literature as are his contemporary liberals, such as Taha Hussein. This thesis provides a historical background and a brief literary survey that helps contextualize al-Rafii, the period, and the area he came from. AI-Rafii played an important role in the two literary and intellectual schools during the Arabic literary revival, which extended from the French expedition (1798-1801) to around the middle of the twentieth century. These two schools, known as the Old and the New, vied to shape the literature and thought of Egypt and other Arab countries. The former, led by al-Rafii, promoted a return to classical Arabic styles and tried to strengthen the Islamic identity of Egypt. The latter called for cutting off Egypt from its Arabic history and rejected the dominance and continuity of classical Arabic language. AI-Rafii contributed to the Revival by supporting a line ofthought that has not been favored by pro-Westernization governments, which made his legacy almost forgotten. Deriving his literature from the canon of Arabic language, culture, and history, al-Rafii produced a literature based on a revived version of classical Arabic literature, an accomplishment which makes him unique among modem Arab writers. -

The History of Arabic Sciences: a Selected Bibliography

THE HISTORY OF ARABIC SCIENCES: A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Mohamed ABATTOUY Fez University Max Planck Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Berlin A first version of this bibliography was presented to the Group Frühe Neuzeit (Max Planck Institute for History of Science, Berlin) in April 1996. I revised and expanded it during a stay of research in MPIWG during the summer 1996 and in Fez (november 1996). During the Workshop Experience and Knowledge Structures in Arabic and Latin Sciences, held in the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin on December 16-17, 1996, a limited number of copies of the present Bibliography was already distributed. Finally, I express my gratitude to Paul Weinig (Berlin) for valuable advice and for proofreading. PREFACE The principal sources for the history of Arabic and Islamic sciences are of course original works written mainly in Arabic between the VIIIth and the XVIth centuries, for the most part. A great part of this scientific material is still in original manuscripts, but many texts had been edited since the XIXth century, and in many cases translated to European languages. In the case of sciences as astronomy and mechanics, instruments and mechanical devices still extant and preserved in museums throughout the world bring important informations. A total of several thousands of mathematical, astronomical, physical, alchemical, biologico-medical manuscripts survived. They are written mainly in Arabic, but some are in Persian and Turkish. The main libraries in which they are preserved are those in the Arabic World: Cairo, Damascus, Tunis, Algiers, Rabat ... as well as in private collections. Beside this material in the Arabic countries, the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek in Berlin, the Biblioteca del Escorial near Madrid, the British Museum and the Bodleian Library in England, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the Süleymaniye and Topkapi Libraries in Istanbul, the National Libraries in Iran, India, Pakistan.. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

The Nile and the Egyptian Revolutions: Ecology and Culture in Modern Arabic Poetry 2015

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 2, Issue 5, May 2015, PP 84-95 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) The Nile and the Egyptian Revolutions: Ecology and Culture in Modern Arabic Poetry 2015 Hala Ewaidat Assistant Professor of English Literature, Department of English, Faculty of Education, Mansoura University, Egypt ABSTRACT For more than thirty years the River Nile has been deteriorating as a result of the industrial activities, economic expansion, pollution, population growth and the destructive policies of the government of the former president Hosni Mubarak. The primary concern of this study is to introduce the profound connection of environmental changes on the River Nile and the culture of the Egyptian society that is reflected through the medium of twentieth century Arabic poetry. Beginning with excerpts of poems from the ancient period, the paper traces the relevance and meaning of the underlying cultural aspects of Egyptian society through representation of the Nile in comparison to the way these cultural attitudes are depicted in poetry written during the three major revolutions in twentieth century Egypt: the 1919 Revolution, 1952 Revolution, and the 25 January 2011 Revolution. Keywords: ecology, pollution, culture, revolutions, Arabic poetry For more than thirty years the River Nile has deteriorated as a result of the industrial activities, economic expansion, pollution, population growth and destructive policies of the regime of the former president Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011). The primary concern of this study is to examine the profound connection between the image of the River Nile in ancient and modern Egyptian poetry and its relation to the ecological changes to the River during the three major revolutions in Egypt: the 1919 Revolution, 1952 Revolution, and the 25 January 2011 Revolution. -

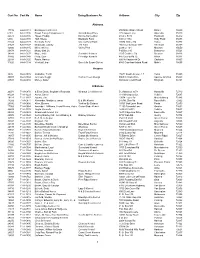

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Ivan Franko MOSES Translated by Vera Rich

Ivan Franko MOSES Translated by Vera Rich PROLOGUE My people, tortured utterly and shattered, Like a poor cripple at the cross-roads lying, By man's contempt, as if with scabs, bespattered! My soul is filled for you with care and sighing, And burning shame permits my sleeping never, To see the fate before your children lying! Can it be some iron decalogue for ever Names you dung 'neath your neighbours' feet, the cattle Drawing the chariot of their swift endeavour? Or that your destiny must show its mettle In hate concealed, humility pretended, To all who by betrayal or in battle Have fettered you, forced you to swear dependence? Are you alone granted no deed of wonder, Which would reveal your powers without ending? Or that in vain for you so great a number Of hearts burned in love's holiest oblation, Offering soul and body for you humbly? In vain your landscape soaked with a libation Of the blood of your heroes? And forbidden The joys of beauty, healing, liberation? In vain the sparks within your language hidden Of might and softness, power and humour thronging, All that can lift the soul to peaks untrodden? In vain your music flows with notes of longing, And chiming laughter, ecstasy of loving, Of hopes and joys in a shaft bright and songful? Ivan Franko. Moses. Tr. Vera Rich 2 O no! Not only tears and sighs will hover Over you. For I trust the mighty spirit That shall your resurrection day discover! O could I start a wave that hears words quiver, And start a word whose bright illumination Will fill that wave with living fire forever! Or start a song, afire with inspiration, A song to stir the multitudes, to lead them, Winging them on the way towards salvation. -

Al-Kindi, a Ninth-Century Physician, Philosopher, And

AL-KINDI, A NINTH-CENTURY PHYSICIAN, PHILOSOPHER, AND SCHOLAR by SAMI HAMARNEH FROM 9-12 December, I962, the Ministry of Guidance in Iraq celebrated the thousandth anniversary of one of the greatest intellectual figures of ninth century Baghdad, Abui Yuisuf Ya'qiib ibn Ishaq al-Kind? (Latin Alkindus).1 However, in the aftermath ofthis commendable effort, no adequate coverage of al-Kindl as a physician-philosopher ofardent scholarship has, to my knowledge, been undertaken. This paper, therefore, is intended to shed light on his intel- lectual contributions within the framework of the environment and time in which he lived. My proposals and conclusions are mainly based upon a study of al-Kindi's extant scientific and philosophical writings, and on scattered information in the literature of the period. These historical records reveal that al-Kindi was the only man in medieval Islam to be called 'the philosopher of the Arabs'.2 This honorary title was apparently conferred upon him as early as the tenth century if not during his lifetime in the ninth. He lived in the Abbasids' capital during a time of high achievement. As one of the rare intellectual geniuses of the century, he con- tributed substantially to this great literary, philosophic, and scientific activity, which included all the then known branches of human knowledge. Very little is known for certain about the personal life of al-Kind?. Several references in the literary legacy ofIslam, however, have assisted in the attempt to speculate intelligently about the man. Most historians of the period confirm the fact that al-Kindl was of pure Arab stock and a rightful descendant of Kindah (or Kindat al-Muliuk), originally a royal south-Arabian tribe3. -

I. Ara Dönem'den Orta Kralliğa (M.Ö. 2200-1950)

Ankara Üniversitesi SBF Dergisi, Cilt 70, No. 3, 2015, s. 683 - 721 I. ARA DÖNEM’DEN ORTA KRALLIĞA (M.Ö. 2200-1950): MISIR DEVLETİ’NDE “YAYILMACI” İDEOLOJİNİN OLUŞUMU ve AŞAĞI NÜBYE’YE UYGULANIŞI * Yrd. Doç. Dr. İzzet Çıvgın Mardin Artuklu Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi ● ● ● Öz Çalışma, tarihteki kültürel karşılaşma (ticaret, öykünme, kolonileşme, fetih/ilhak) örnekleri ile bunların toplumsal ve siyasal değişmeye katkısını inceleyen makaleler dizisinin sekizincisini oluşturmaktadır. Metnin temel argümanı, Mısır Orta Krallığı‟nın (MÖ. 2050-1750) güney/Nübye yönünde başlattığı kolonileşmenin tarihsel arka-planının “1. Ara Dönem”de (2200-2050) yaşanan fetret devri ve merkezî iktidarın krizi olduğudur. Eski Krallık (2700-2200) rejiminin çözüldüğü ve kraliyet otoritesindeki zafiyetten dolayı Mısır eyaletlerinin merkezden bağımsızlaştığı bir ortamda, sarayın ekonomik ve siyasal tekeli kırılmış, doğal kaynakların merkez yerine taşraya aktığı yeni bir düzen kurulmuştur. Bu yerelleşmenin (âdemimerkeziyetin) kalıcı olmamasının nedeni ise, Mısır devlet ideolojisinde siyasal birliğin ve merkeziyetçi hiyerarşinin “ideal” görülüp kutsanmasıdır. Ara dönemler, aşılması gereken, istikrarsızlık ve bereketsizlik üreten “kaotik” zamanlardır. Orta (Herakleopolis) ve Yukarı Mısır‟da (Thebai) ortaya çıkan yerel iktidar odakları, bu anlayış doğrultusunda Eski Krallık düzenini yeniden kurmak (“ideal”i yakalamak) için birbirleriyle kıyasıya mücadele etmişlerdir. Değişen, Ara Dönem‟de siyasal birlik için zorunlu kabul edilen “genişleme”nin Orta Krallıkta sınır güvenliği, siyasal istikrar ve daha fazla servet birikimi için sürdürülmesidir. Anahtar Sözcükler: 1. Ara Dönem, Mısır Orta Krallığı, Aşağı ve Yukarı Nübye, Medjay ve C-Grup Kültürleri, Kerma Kültürü i The First Intermediate Period and the Early Middle Kingdom (2200- 1950 BC.):Origins of Ancient Egyptian Imperialism in Lower Nubia Abstract This study is the 8th of an article series dedicated to cross-cultural encounters (trade, emulation, colonization, conquest) as a primary cause of social and political change.