Schmitz, Richard F. 1988. Understanding Scolytid Problems In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Pityogenes Knechteli (Swaine) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in Lodgepole Pine

" "SEMIOCHEMICAL-BASED COMMUNICATION IN INTERSPECIFIC INTERACTIONS BETWEEN IPS PINI (SAY) AND PITYOGENES KNECHTELI (SWAINE) (COLEOPTERA: SCOLYTIDAE) IN LODGEPOLE PINE . THERESE M. POLAND and JOHN H. BORDEN Centre forPest Management,Department of Biological Sciences, SimonFraser University, Bumaby, l BritishColumbia,Canada V5A 1S6 ,_._, _ ::._.., _.,.... Abstract The Canadian Entomologist 126:269-276 (1994) .,:.... _ , . , a The pine engraver, Ips pini Say, and Pityogenes knechteli Swaine often co-exist in " , lodgepole pine, Pinus contorta var. latifolia Engelmann. We tested the hypotheses that ,.. " P. knechteli produces an attractive pheromone and that the attraction of P. knechteli and _%_'.. • I. pini to conspecifics is inhibited by the presence of the other species. Pityogenes ._:,: knechteli males and females were attracted to bolts infested with conspecific males and •. , , to bolts infested with I. pini males; however, there was no significant cross-attraction of ...... •: _ - I. pini males or females to bolts infested with P. knechteli males. Attraction ofP. knechteli " :;• _ ..... ,and I. pini males and females to bolts infested with conspecific males was not inhibited • ,. ._ in the presence of bolts infested with males of the other bark beetle species. Pityogenes .... knechteli has no potential for compe.titive displacement of I. pini but may enhance the adverse effectof I. pini on.the mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins. ; Poland, T.M., et J.H. Borden. 1994. Communication s6mio-chimique lors des interactions _e.. ., intersp6cifiquesentreIpspini (Say)et Pityogenesknechteli (Swaine) (Coleoptera:Scolytidae) " " chez le Pin de Murray.The Canadian Entomologist 126:269-276 ? R_sum_ • _ ' Les scolytes Ips pini Say et Pityogenes knechteli Swaine cohabitent souvent dans des ' '_7:.':_ ......:'_:_::'_ Pins de Murray Pinus contorta var. -

Seasonality and Lure Preference of Bark Beetles (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and Associates in a Northern Arizona Ponderosa Pine Forest

COMMUNITY AND ECOSYSTEM ECOLOGY Seasonality and Lure Preference of Bark Beetles (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and Associates in a Northern Arizona Ponderosa Pine Forest 1,2 1 3 1 M. L. GAYLORD, T. E. KOLB, K. F. WALLIN, AND M. R. WAGNER Environ. Entomol. 35(1): 37Ð47 (2006) ABSTRACT Ponderosa pine forests in northern Arizona have historically experienced limited bark beetle-caused tree mortality, and little is known about the bark beetle community in these forests. Our objectives were to describe the ßight seasonality and lure preference of bark beetles and their associates in these forests. We monitored bark beetle populations for 24 consecutive months in 2002 and 2003 using Lindgren funnel traps with Þve different pheromone lures. In both years, the majority of bark beetles were trapped between May and October, and the peak captures of coleopteran predator species, Enoclerus (F.) (Cleridae) and Temnochila chlorodia (Mannerheim), occurred between June and August. Trap catches of Elacatis (Coleoptera: Othniidae, now Salpingidae), a suspected predator, peaked early in the spring. For wood borers, trap catches of the Buprestidae family peaked in late May/early June, and catches of the Cerambycidae family peaked in July/August. The lure targeted for Dendroctonus brevicomis LeConte attracted the largest percentage of all Dendroc- tonus beetles except for D. valens LeConte, which was attracted in highest percentage to the lure targeted for D. valens. The lure targeted for Ips pini attracted the highest percentage of beetles for all three Ips species [I.pini (Say), I. latidens (LeConte), and I. lecontei Swaine] and the two predators, Enoclerus and T. chlorodia. -

Dendroctonus Beetles and Old-Growth Forests in the Rockies

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Quinney Natural Resources Research Library, The Bark Beetles, Fuels, and Fire Bibliography S.J. and Jessie E. 1992 Dendroctonus Beetles and Old-Growth Forests in the Rockies J M. Schmid G D. Amman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/barkbeetles Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Recommended Citation Schmid, J. and Amman, G. (1992). Dendroctonus beetles and old-growth forests in the Rockies. In: MR Kaufmann, WH Moir and WH Bassett (tech.eds) Old-growth Forest in the Southwest and Rock Mountain Regions, Proceedings of a Workshop (pp. 51-59). USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, General Technical Report RM-GTR-213. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Quinney Natural Resources Research Library, S.J. and Jessie E. at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bark Beetles, Fuels, and Fire Bibliography by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dendroctonus Beetles and Old-Growth Forests in the Rockies1 J. M. Schmid and G. D. Amman2 Abstract.-Dendroctonus beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) are a major mortality agent in old growth pine, spruce-fir, and Douglas-fir forests of the Rocky Mountains. The frequency of recurring bark beetle epidemics depends on the size of the area being considered, how extensively the stand(s) was decimated by a previous epidemic(s), and how fast the stand(s) grows into the hazardous condition. -

Psw 2020 Fettig006 Audley.Pdf

Forest Ecology and Management 475 (2020) 118403 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Impacts of mountain pine beetle outbreaks on lodgepole pine forests in the T Intermountain West, U.S., 2004–2019 ⁎ Jackson P. Audleya, Christopher J. Fettiga, , A. Steven Munsonb, Justin B. Runyonc, Leif A. Mortensond, Brytten E. Steede, Kenneth E. Gibsone, Carl L. Jørgensenf, Stephen R. McKelveya, Joel D. McMilling, Jose F. Negrónh a Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1731 Research Park Drive, Davis, CA95618,USA b Forest Health Protection, USDA Forest Service, 4746 South 1900 East, Ogden, UT 84403, USA c Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1648 South 7th Avenue, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA d Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 2480 Carson Road, Placerville, CA 95667,USA e Forest Health Protection, USDA Forest Service, 26 Fort Missoula, Missoula, MT 59804, USA f Forest Health Protection, USDA Forest Service, 1249 South Vinnell Way, Suite 200, Boise, ID 83709, USA g Forest Health Protection, USDA Forest Service, 2500 South Pine Knoll Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA h Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 240 West Prospect Road, Fort Collins, CO 80526, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), is the most important forest Bark beetles insect in western North America. We determined causes and rates of tree mortality and changes in forest Climate change structure and composition associated with D. ponderosae outbreaks in the Intermountain West, U.S. during Dendroctonus ponderosae 2004–2019 based on a network of 125 0.081-ha circular plots installed in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah and Disturbance Wyoming. -

Insect Infestation of Fire- Injured'trees in the Greater Yellowstone Area

/11... United States Department of Agriculture Insect Infestation of Fire Forest Service Injured'Trees in the • Intermountain Research Station Research Note Greater Yellowstone Area INT-398 September 1991 Gene D. Amman1 Kevin c. Ryan2 ABSTRACT Survival of conifers following fire depends on the type and degree of injuries sustained, initial tree Permanent plots were established in the Greater vigor, and the postfire environment, including Yellowstone Area (GYA,) following the 1988 fires to weather and insect and disease population dynam determine response of bark beetles to fire-injured ics (Ryan 1982, 1990). As fire injuries increase, the conifers. Within 2 years (1989 and 1990), 67 percent probability of tree death increases. Numerous of the Douglas-(z.r had been infested by bark beetles authors (compare Peterson 1985; Peterson and (primarily the Douglas-fir beetle) and wood borers; Arbaugh 1986, 1989; Ryan 1990; Ryan and others 44 percent of the lodgepole pine were infested (prima 1988) have identified the proportion of crown killed rily by the pine engraver); 82 percent of the Engel as the key injury contributing to death of most mann spruce were infested (mostly by spruce beetle); trees, but injuries to bole cambium or roots or both and 71 percent of the subalpine fir were infested may dominate in some cases (Ferguson and others (mostly by wood borers). Bark beetle infestation 1960; Ryan and others 1988; Ryan and Reinhardt usually occurred in trees having 50 percent or more 1988). Resistance to cambium injury increases with • basal girdling by fire. However, uninjured Douglas the square of the bark thickness (compare Martin fir also had 46 percent of the trees infested in 1990. -

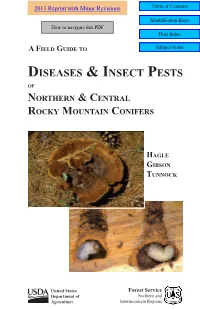

A Field Guide to Diseases and Insect Pests of Northern and Central

2013 Reprint with Minor Revisions A FIELD GUIDE TO DISEASES & INSECT PESTS OF NORTHERN & CENTRAL ROCKY MOUNTAIN CONIFERS HAGLE GIBSON TUNNOCK United States Forest Service Department of Northern and Agriculture Intermountain Regions United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service State and Private Forestry Northern Region P.O. Box 7669 Missoula, Montana 59807 Intermountain Region 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/r4/forest-grasslandhealth Report No. R1-03-08 Cite as: Hagle, S.K.; Gibson, K.E.; and Tunnock, S. 2003. Field guide to diseases and insect pests of northern and central Rocky Mountain conifers. Report No. R1-03-08. (Reprinted in 2013 with minor revisions; B.A. Ferguson, Montana DNRC, ed.) U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, State and Private Forestry, Northern and Intermountain Regions; Missoula, Montana, and Ogden, Utah. 197 p. Formated for online use by Brennan Ferguson, Montana DNRC. Cover Photographs Conk of the velvet-top fungus, cause of Schweinitzii root and butt rot. (Photographer, Susan K. Hagle) Larvae of Douglas-fir bark beetles in the cambium of the host. (Photographer, Kenneth E. Gibson) FIELD GUIDE TO DISEASES AND INSECT PESTS OF NORTHERN AND CENTRAL ROCKY MOUNTAIN CONIFERS Susan K. Hagle, Plant Pathologist (retired 2011) Kenneth E. Gibson, Entomologist (retired 2010) Scott Tunnock, Entomologist (retired 1987, deceased) 2003 This book (2003) is a revised and expanded edition of the Field Guide to Diseases and Insect Pests of Idaho and Montana Forests by Hagle, Tunnock, Gibson, and Gilligan; first published in 1987 and reprinted in its original form in 1990 as publication number R1-89-54. -

An Analysis of the Larval Instars of the Walnut Twig Beetle, Pityophthorus Juglandis Blackman (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), in North

An analysis of the larval instars of the walnut twig beetle, Pityophthorus juglandis Blackman (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), in northern California black walnut, Juglans hindsii, and a new host record for Hylocurus hirtellus Author(s): Paul L. Dallara, Mary L. Flint, and Steven J. Seybold Source: Pan-Pacific Entomologist, 88(2):248-266. 2012. Published By: Pacific Coast Entomological Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3956/2012-16.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3956/2012-16.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. THE PAN-PACIFIC ENTOMOLOGIST 88(2):248–266, (2012) An analysis of the larval instars of the walnut twig beetle, Pityophthorus juglandis Blackman (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), in northern California black walnut, Juglans hindsii, and a new host record for Hylocurus hirtellus 1 1 2 PAUL L. DALLARA ,MARY L. -

Pinon Ips Bark Beetle

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AZ1394 Revised 03/13 THE PIÑON IPS BARK BEETLE Tom DeGomez and Bob Celaya Figure 1. Extensive piñon mortality from piñon ips induced by drought conditions, Flagstaff, Arizona September, 2003. Within the woodlands of 4,500’ to 7,000’ elevations in the borers (Dioryctria ponderosae), they cause copious amounts Southwest, piñon pine occurs in association with juniper of pitch to flow from wounds and should not be confused (Juniperus spp.) at the lower and ponderosa pine (Pinus with piñon ips. ponderosa) at the higher elevations. Piñon are commonly Piñon ips is a native bark beetle that utilizes piñon pine utilized by a small bark beetle – piñon ips, Ips confusus. inner bark and outer sapwood for food and to rear offspring, Since these beetles are from the Ips genus of bark beetles spending most of their lives underneath the bark of the tree. they are also known as engraver beetles. Piñon ips will When a new generation of adults emerge from an infested utilize, Colorado piñon (P. edulis) and single leaf piñon (P. tree they may re-infest the same tree or fly short distances monophylla) and occasionally other pines in the Southwest. Juniper and ponderosa species that are generally associated with piñon are not affected by piñon ips. Junipers in these woodlands are attacked by cedar, cypress, or juniper bark AT A GLANCE beetles in the Phloeosinus genus and woodborers. Ponderosa pine is attacked by pine bark beetles in the genus Ips and • Hosts, Description and Life Cycle of Piñon Ips Dendroctonus. -

Pest Categorisation of Non‐

SCIENTIFIC OPINION ADOPTED: 20 November 2019 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.5934 Pest categorisation of non-EU Scolytinae of coniferous hosts EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLH), Claude Bragard, Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz, Francesco Di Serio, Paolo Gonthier, Marie-Agnes Jacques, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Annemarie Fejer Justesen, Alan MacLeod, Christer Sven Magnusson, Juan A Navas-Cortes, Stephen Parnell, Roel Potting, Philippe Lucien Reignault, Hans-Hermann Thulke, Wopke Van der Werf, Antonio Vicent Civera, Jonathan Yuen, Lucia Zappala, Jean-Claude Gregoire, Virag Kertesz, Franz Streissl and Panagiotis Milonas Abstract The Panel on Plant Health performed a pest categorisation of non-EU Scolytinae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) of coniferous hosts (hereafter NESC). NESC occur worldwide, and some species are important forest pests. Species can be identified using taxonomic keys and molecular methods. Most NESC species (bark beetles) live in the inner bark of their hosts (phloem and cambium), while the remaining species mostly colonise the sapwood (ambrosia beetles). Bark- and ambrosia beetles are often associated with symbiotic fungi, which behave as pathogens towards the host trees, or are used as food by ambrosia beetle larvae. The larvae live in individual tunnels or in communal chambers. Pupation occurs in the wood or in the bark. Some species are semi- or multivoltine, others are monovoltine. Some species attack and kill living, apparently healthy trees. Other species specialise in weakened, dying or dead trees. The pathways for entry are cut branches, cones, round wood with or without bark, sawn wood with or without bark, wood packaging material, bark, manufactured wood items and wood chips and plants for planting (including seeds) of conifers. -

Molecular Phylogeny and Taxonomic Review of Premnobiini Browne, 1962 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 29 November 2013 ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION doi: 10.3389/fevo.2013.00001 Molecular phylogeny and taxonomic review of Premnobiini Browne, 1962 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) Anthony I. Cognato* Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA Edited by: The taxonomy of Premnobiini is reviewed in the context of a molecular phylogeny Alejandro P.Rooney, U.S. including species of Ipini, Dryocoeotini, and Xyleborini. DNA data from COI, 16S, 28S, Department of Agriculture, USA and CAD (∼2640 characters) were generated for 79 species. Parsimony and Bayesian Reviewed by: methods, using multiple sequence alignment methods and partitioning regimes, were Bjarte H. Jordal, University of Bergen, Norway used to reconstruct the phylogeny. The resulting topologies are generally congruent. Ipini Jiri Hulcr, University of Florida, USA is monophyletic along with all genera except Acathotomicus. Premnobiini is nested within *Correspondence: Ipini and consists of two clades, which associate with the type species of Premnobius Anthony I. Cognato, Department of and Premnophilus, and with morphological diagnostic characters. The following taxonomic Entomology, Michigan State changes are made based on the recovered relationships. Premnophilus is resurrected as University, 288 Farm Lane Road, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA a valid genus and Premnobiini is considered a sub-tribe of Ipini. e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Ipini, systematics, taxonomy, nomenclature, COI, 16S, 28S, CAD INTRODUCTION et al., 2001). Although no nomenclatural changes were made Premnobiini Browne (1962) consists of Premnobius Eichhoff in these studies, subsequent researchers (Beaver, 2005; Bright (1879) and its 26 species that are endemic to sub-Saharan and Torres, 2006; Alonso-Zarazaga and Lyal, 2009)recognized Africa; two of which are considered adventive to the Neotropics Premnobiini based on data from previous studies (Browne, 1961, (Wood, 1982; Wood and Bright, 1992; Bright and Skidmore, 1962; Nobuchi, 1969; Normark et al., 1999). -

Density-Dependent Effects of Multiple Predators Sharing a Common Prey in an Endophytic Habitat

Oecologia (2004) 139: 418–426 DOI 10.1007/s00442-004-1511-9 COMMUNITY ECOLOGY Brian H. Aukema . Murray K. Clayton . Kenneth F. Raffa Density-dependent effects of multiple predators sharing a common prey in an endophytic habitat Received: 13 June 2003 / Accepted: 15 January 2004 / Published online: 13 February 2004 # Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Multiple predator species feeding on a common female basis. The combined effects of these predators did prey can lead to higher or lower predation than would be not enhance or reduce prey establishment or reproduction expected by simply combining their individual effects. in unexpected manners, and these predators were entirely Such emergent multiple predator effects may be especially substitutable. The herbivore’s net replacement rate was prevalent if predators share feeding habitat. Despite the never reduced significantly below one at prey and predator prevalence of endophagous insects, no studies have densities emulating field conditions. Similar numbers of examined how multiple predators sharing an endophytic each predator species emerged from the logs, but predator habitat affect prey or predator reproduction. We investi- reproduction suffered from high intraspecific interference. gated density-dependent predation of Thanasimus dubius The net replacement rate of P. cylindrica was not affected (Coleoptera: Cleridae) and Platysoma cylindrica (Coleop- by conspecifics or T. dubius. In contrast, the net tera: Histeridae) on a bark beetle prey, Ips pini (Coleop- replacement rate of T. dubius decreased with the presence tera: Scolytidae), in a laboratory assay. I. pini utilize of conspecifics or P. cylindrica. Combinations of both aggregation pheromones to group-colonize and reproduce predators led to an emergent effect, a slightly increased net within the stems of conifers. -

Field Guide to Diseases & Insects of the Rocky Mountain Region

United States Department of Agriculture / Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region, Forest Health Protection Rocky Mountain Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-241 December 2010 Rocky Mountain Region, Forest Health Protection. 2010. Field guide to diseases & insects of the Rocky Mountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-241 Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 336 p. Abstract This field guide is a forest management tool for field identification of biotic and abiotic agents that damage native trees in Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, which constitute the USDA Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Region. The guide focuses only on tree diseases and forest insects that have significant economic, ecological, and/ or aesthetic impacts; this guide does not necessarily cover all possible damage agents. Management suggestions are provided where available. The field guide is divided into two sections: one describes both diseases and damage caused by animals and abiotic factors, and the other describes insects. Agents are presented by the type and/or location of the injury on the tree. Written descriptions, color photographs, a general index, an index by host tree species, descriptive tables, and line drawings are all provided to assist users in identifying damaging agents. You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. Please specify the publication title and series number. Publishing Services Telephone (970) 498-1392 FAX (970) 498-1122 E-mail [email protected] Web site http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/publications Mailing address Publications Distribution Rocky Mountain Research Station 240 West Prospect Road Fort Collins, CO 80526 Authors Kurt K.