B & W (Walter Biermann and Johannes Weber), Berlin, Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carl Zeiss, 32, Wagnergasse, Jena, Germany. ((1847) Also: 29/II Dorotheen Strasse 29, Berlin, Germany

Carl Zeiss, 32, Wagnergasse, Jena, Germany. ((1847) also: 29/II Dorotheen strasse 29, Berlin, Germany. (1901) and 29, Margaret St, Regent St, London W (1901) The founder, Carl Zeiss (1816-1888) was born in Weimar, the son of a cabinet maker and ivory carver. He graduated from school in 1834, qualified to be apprenticed to the Grand Dukes Instrument maker, Dr Koerner, and attended academic courses as well as working as apprentice. Next he travelled from Jan. 1838 to Oct. 1845 to study in Stuttgart, Darmstadt, Vienna, and Berlin to broaden his experience. Back at home, he studied chemistry and higher mathematics. By May 1845, he felt well enough qualified to apply to the County Administration at Weimar for permission to found "An establishment for the production of advanced mechanical devices", hoping for a relationship with the University to advance designs. Money was tight with capital of 100 Thalers (possibly £100) only, but in Nov. 1846, he opened at 7, Neugasse. It remained a small business for years, as it took some 20 years for the University relationship to be productive, and he often grew weary of the trial and error methods traditionally used in the trade. Much of the production was of microscopes- often relatively simple ones by modern standards, such as dissection viewers. Then in 1863, a young lecturer Ernst Abbe (1840-1905) joined the University to teach physics and astronomy. Zeiss approached him in 1866 for cooperation in the design of improved systems and this lead to new ideas, eg in the Abbe refractometer (1869), a comparator and a spectrometer. -

Tessar and Dagor Lenses

Tessar and Dagor lenses Lens Design OPTI 517 Prof. Jose Sasian Important basic lens forms Petzval DB Gauss Cooke Triplet little stress Stressed with Stressed with Low high-order Prof. Jose Sasian high high-order aberrations aberrations Measuring lens sensitivity to surface tilts 1 u 1 2 u W131 AB y W222 B y 2 n 2 n 2 2 1 1 1 1 u 1 1 1 u as B y cs A y 1 m Bstop ystop n'u' n 1 m ystop n'u' n CS cs 2 AS as 2 j j Prof. Jose Sasian Lens sensitivity comparison Coma sensitivity 0.32 Astigmatism sensitivity 0.27 Coma sensitivity 2.87 Astigmatism sensitivity 0.92 Coma sensitivity 0.99 Astigmatism sensitivity 0.18 Prof. Jose Sasian Actual tough and easy to align designs Off-the-shelf relay at F/6 Coma sensitivity 0.54 Astigmatism sensitivity 0.78 Coma sensitivity 0.14 Astigmatism sensitivity 0.21 Improper opto-mechanics leads to tough alignment Prof. Jose Sasian Tessar lens • More degrees of freedom • Can be thought of as a re-optimization of the PROTAR • Sharper than Cooke triplet (low index) • Compactness • Tessar, greek, four • 1902, Paul Rudolph • New achromat reduces lens stress Prof. Jose Sasian Tessar • The front component has very little power and acts as a corrector of the rear component new achromat • The cemented interface of the new achromat: 1) reduces zonal spherical aberration, 2) reduces oblique spherical aberration, 3) reduces zonal astigmatism • It is a compact lens Prof. Jose Sasian Merte’s Patent of 1932 Faster Tessar lens F/5.6 Prof. -

Cooke Triplet

Cooke triplet Lens Design OPTI 517 Prof. Jose Sasian Cooke triplet • A new design • Enough variables to correct all third– order aberrations • Thought of as an afocal front and an imaging rear • 1896 • Harold Dennis Taylor Prof. Jose Sasian Cooke triplet field-speed trade-off’s 24 deg @ f/4.5 27 deg @ f/5.6 Prof. Jose Sasian Aberration correction • Powers, glass, and separations for: power, axial chromatic, field curvature, lateral color, and distortion. Lens bendings, for spherical aberration, coma, and astigmatism. Symmetry. •Power: yaa ybb ycc ya 2 2 2 •Axial color: ya a /Va yb b /Vb yc c /Vc 0 • Lateral color: ya yaa /Va yb ybb /Vb yc ycc /Vc 0 • Field curvature: a / na b / nb c / nc 0 Prof. Jose Sasian • Crossing of the sagittal and tangential field is an indication of the balancing of third-order, fifth-order astigmatism, field curvature, and defocus. Prof. Jose Sasian The strong power of the first positive lens leads to spherical aberration of the pupil which changes the chief ray high whereby inducing significant higher order aberrations. Y y ay 3 Y 2 y 2 2ay 4 a2 y 6 2 W222 Y 2 W422 ay W222 Prof. Jose Sasian Cooke triplet example from Geiser OE •5 waves scale •visible F1=34 mm F2=-17 mm F3=24 mm 1 STANDARD 23.713 4.831 LAK9 2 STANDARD 7331.288 5.86 STO STANDARD -24.456 0.975 SF5 4 STANDARD 21.896 4.822 5 STANDARD 86.759 3.127 LAK9 6 STANDARD -20.4942 41.10346 IMA STANDARD Infinity From Geiser OE f/4 at +/- 20 deg. -

Carl Zeiss Oberkochen Large Format Lenses 1950-1972

Large format lenses from Carl Zeiss Oberkochen 1950-1972 © 2013-2019 Arne Cröll – All Rights Reserved (this version is from October 4, 2019) Carl Zeiss Jena and Carl Zeiss Oberkochen Before and during WWII, the Carl Zeiss company in Jena was one of the largest optics manufacturers in Germany. They produced a variety of lenses suitable for large format (LF) photography, including the well- known Tessars and Protars in several series, but also process lenses and aerial lenses. The Zeiss-Ikon sister company in Dresden manufactured a range of large format cameras, such as the Zeiss “Ideal”, “Maximar”, Tropen-Adoro”, and “Juwel” (Jewel); the latter camera, in the 3¼” x 4¼” size, was used by Ansel Adams for some time. At the end of World War II, the German state of Thuringia, where Jena is located, was under the control of British and American troops. However, the Yalta Conference agreement placed it under Soviet control shortly thereafter. Just before the US command handed the administration of Thuringia over to the Soviet Army, American troops moved a considerable part of the leading management and research staff of Carl Zeiss Jena and the sister company Schott glass to Heidenheim near Stuttgart, 126 people in all [1]. They immediately started to look for a suitable place for a new factory and found it in the small town of Oberkochen, just 20km from Heidenheim. This led to the foundation of the company “Opton Optische Werke” in Oberkochen, West Germany, on Oct. 30, 1946, initially as a full subsidiary of the original factory in Jena. -

Since Questions About Docter Optic Lenses Come up in This

Large Format Lenses from Docter Optic 1991-1996 © 2003-2020 Arne Cröll – All Rights Reserved (this version is from July 16, 2020 – the first version of this article appeared in “View Camera” Sept./Oct. 2003) Docter Optic and Carl Zeiss Jena Docter Optic was originally a small West-German optics company, founded in 1984 by the late Bern- hard Docter - hence the company name, no relation to academic titles or a medical background [1-3]. They were located in Schwalbach near Wetzlar and made projection and lighting optics, car headlight optics, etc., mostly as supplier for original equipment manufacturers (OEM). Their specialty was a glass blank molding process for aspherical optical elements, invented by Bernhard Docter. The com- pany expanded later with two more production facilities in and near Wetzlar. In 1989 they bought an Austrian subsidiary, which had originally been the optics department of Eumig, an Austrian manufac- turer of home movie projectors. Also in 1989, the Berlin wall came down. Subsequently, Germany was reunited in October 1990, followed by the privatization of the nationalized companies of the GDR through the “Treuhand” trustee management that took over those companies. This included the VEB Carl Zeiss Jena and all its production facilities as described in another article [4]. Docter Optic bought several plants of the for- mer VEB Carl Zeiss Jena in 1991. In August of that year, Docter acquired the production facilities in Saalfeld, Thuringia, the former “OAS” plant, which had produced most of the Carl Zeiss Jena photo- graphic optics in the GDR. Docter also bought another Carl Zeiss Jena plant making binoculars and rifle sights in nearby Eisfeld at the same time, as well as a third Zeiss plant making optical components in Schleiz. -

· Could Colortv.

Sales assistants. Yourproduct knowledg,l · could you 1st prize of a Philips 2Z' colorTv... • •••or one of a hundred Kodak pocket Instamatic 100 camera outfits! Win - - a color T.V. set, or one of 100 Kodak ~ocke t lnstamatic 100 camer a outfits!! nn. Your Name: Mr./ Mrs.I Miss __ __ ____ __ ______________ _ ~illdakPocket Store Name and addre ss _ __ ____ ___ _ ______________ _ Camera Quiz Post your entry to : Kodak pocket camera qu iz, P.O. Box 90, Coburg , Vict oria, 3058. to arrive on or before Friday November 15, 1974. 01. What are the two best selling featur es Q8. (B) You go on to explain that the 014. Your customer now has a box camera of all Kod ak pocket lnstamatic model 300 is even better, beca use: and says " I want a camera that is easy came ras? LJ Automatic exposure control to load, and doesn't doubl e-expose." pact , lightweight , easy to carry You explain th at poc ket lnstamatic Variab le apert ure lens enab les cameras: ht-line viewfind er D pictures under a wider range of D Load automatica lly t::'. e big , clear, rectangu lar picture s lighting conditi ons. lJ Reliable flash pictu res [J Warnin g sign al warns of underexposure D Can't be wound on unless the safety - • Tripod and cable release sockets switch is pressed 02. Pock et lnstamatic cameras use: Extended 1.2- 5 m. fl ash pictur e range • Have s:mple drop-in cartridge load ing, [J 126 fil m O 828 film • and a doub le-ex posure prevention lock . -

ARRI Large Format Camera System

Jon Fauer ASC Camera Type Large Format (LF) film-style digital camera with an electronic viewfinder, LF Open Gate, LF 16:9 and LF 2.39:1 switchable active sensor area, built-in radios for the ARRI Wireless Remote System, the ARRI Wireless Video System and WiFi, built-in LF FSND filter holder, Lens Data System LDS-1, LDS-2, /i, integrated shoulder arch and receptacles for 15 mm lightweight rods. Ideal for High Dynamic Range and Wide Color Gamut recording and monitoring.SensorLarge Format (36.70 x 25.54 mm) ALEV III CMOS sensor with Bayer pattern color filter array.Photo SitesSensor Mode LF Open Gate (36.70 x 25.54 mm, Ø 44.71 mm)4448 x 3096 used for LF Open Gate ARRIRAW 4.5K4448 x 3096 used for LF www.fdtimes.com Open Gate ProRes 4.5KSensor Mode LF 16:9 (31.68 x 17.82 mm, Ø 36.35 mm)3840 x 2160 used for LF 16:9 ARRIRAW UHD3840 x 2160+113° used F) for@ 70%LF 16:9 humidity ProRes max, UHD3840 non-condensing. x 2160 down Splash and dust proof through sampled to 2048 x 1152 for LF 16:9 ProRes 2K3840 x 2160 down sampled to 1920 x 1080 for LF 16:9 ProRes HDSensor Mode LF 2.39:1 (36.70 x 15.31 mm,Ø 39.76 mm)4448 x 1856 used for LF 2.39:1 ARRIRAW 4.5K4448 x 1856 used for LF 2.39:1 ProRes 4.5KOperating ModesLF Open Gate, LF 16:9 or LF(-4° 2.39:1 F to sensor modes. -

Kodak Flash Bantam Manual

Kodak Flash Bantam Manual Eastman Kodak Co., of Rochester, New York, is an American film maker and camera maker. 3.3.21 130 film, 3.3.22 616 film, 3.3.23 620 film, 3.3.24 828 Bantam film Flash II Camera, Brownie Flash III Camera, Brownie Flash IV Camera, Kodak Kodak manuals, booklets and other historical literature (some in PDF. Kodak Bantam. Kodak Anastigmat lens f.6.3. 8-37-KP-35. Kodak Flash News! 5/59/6 TF300656 Kodak and Kodak Brownie user manuals from the collection. Digital camera instruction manuals brought to you by OTC. Original and professionally produced copies of digital camera manuals for (Flash Bantam f4.5) One in particular, a Kodak Flash Bantam, which was a gift from my dearly departed grandmother, was the inspiration for the project described in this article. More Like This. KODAK FLASH BANTAM, 48/4.5 KODAK ANAS$20.00 · Vintage Kodak Tourist Camera Manual 1$4.50 · KODAK FLASH BANTAM CAMERA. etsy.com. Kodak Camera Flash Bantam with Leather Case by jackscloset, $48.00 Kodak No. 2 Folding Cartridge Premo Camera with Original Box & Manual. Kodak Flash Bantam Manual Read/Download RARE Kodak Flash Bantam 828 Roll Film Folding Camera Lense = Anastar Vintage Lot Original Boxes- Kodak Bantam RF Camera & Field Case + Manual. Kodak Film Camera 1600 Auto. Kodak Film Camera User Manual. Pages: 0 Saves: 0. See Prices Buy or Upgrade. 828 special 35mm paper backed roll film and was equipped with a non-self-cocking Flash 300 shutter and 50mm f/3.9 Kodak Ektanon lens. -

3D Frequently Asked Questions

3D Frequently Asked Questions Compiled from the 3-D mailing list 3D Frequently Asked Questions This document was compiled from postings on the 3D electronic mail group by: Joel Alpers For additions and corrections, please contact me at: [email protected] This is Revision 1.1, January 5, 1995 The information in this document is provided free of charge. You may freely distribute this document to anyone you desire provided that it is passed on unaltered with this notice intact, and that it be provided free of charge. You may charge a reasonable fee for duplication and postage. This information is deemed accurate but is not guaranteed. 2 Table Of Contents 1 Introduction . 7 1.1 The 3D mailing list . 7 1.2 3D Basics . 7 2 Useful References . 7 3 3D Time Line . 8 4 Suppliers . 9 5 Processing / Mounting . 9 6 3D film formats . 9 7 Viewing Stereo Pairs . 11 7.1 Free Viewing - viewing stereo pairs without special equipment . 11 7.1.1 Parallel viewing . 11 7.1.2 Cross-eyed viewing . 11 7.1.3 Sample 3D images . 11 7.2 Viewing using 3D viewers . 11 7.2.1 Print viewers - no longer manufactured, available used . 11 7.2.2 Print viewers - currently manufactured . 12 7.2.3 Slide viewers - no longer manufactured, available used . 12 7.2.4 Slide viewers - currently manufactured . 12 8 Stereo Cameras . 13 8.1 Currently Manufactured . 13 8.2 Available used . 13 8.3 Custom Cameras . 13 8.4 Other Techniques . 19 8.4.1 Twin Camera . 19 8.4.2 Slide Bar . -

E.A. Eastern Optical, Brooklyn, New York, USA. Ebata A. Ebner and Co

E.A. This engraving was used by E. and H.T. Anthony, New York q.v. It was noted on a No2 Hemispherique Rapide lens . Eastern Optical, Brooklyn, New York, USA. This may be related to Kollmorgen. Anastigmat f6.3 520mm was listed in the USA secondhand. (1962). Ebata This was noted as a Trade Name on an Exakta fit f2.8/135mm pre-set lens, of unknown source. A. Ebner and Co, Gmbh, Vaihingen, Stuttgart, Germany. About 1934, Ebner made a series of folders for 6x9 and 4.5x6cm with bakelite bodies, using Meyer and Zeiss lenses as the expensive ones, but the low cost versions had Ebner Anastigmat f6.3/75mm and f4.5/75mm lenses. Eclaire Cameflex, Paris, France. Formed by Coutant and Mathot in the last Century, this company designed a compact novel 35mm camera during WW2 and released it in 1947 with great success, and it sold well in the UK so that lenses with this bayonet are among the more common 35mm items now on the "old" lens market. It is thought these have a prominent rear stub with a 2 leaf bayonet with a slot cut in one leaf. These can include very desireable Kinoptic and Angenieux items. Eclipse It is worth noting that total eclipses of the sun and other astronomical events bring out some amazing old optics, especially as small apertures may be quite acceptable for some work but fast lenses are also needed during totality. Thus the 1927 eclipse in the UK seems to have been recorded (B.A.A. -

Bolta Photavit Werk

Bolta Photavit Werk Leif Johansen Kort historik: Boltavit kameraet blev konstrueret og bygget i I 1941 kom USA i krig med Nazityskland og 1935. Der var en mere eller mindre parallel Bolten mistede kontrollen, men Photavit Bolta Werk gruppen blev grundlagt af produktion på hver side af Atlanterhavet. Året værket kunne fortsætte med en Johannes Bolten (1893–1982) med en efter blev der i Nürnberg etableret en krigsproduktion baseret på tvangsarbejdere. I startproduktion af bakelitkamme. Bolten selvstændig værksenhed. Studie af maj 1945 undgik Bolten som USA statsborger udvandrede i 1929 til Amerika, skiftede navn kameraudseende og funktioner viser et tæt en beslaglæggelse efter russiske krav. til John Bolten og fik amerikansk samarbejde mellem Boltavit og Ulca fabrikken Samtidig havde den “amerikanske “fabrik statsborgerskab. Han havde succes som (“legetøjs” kamera) med samme konstruktør. nemmere adgang til råvarer og kunne sælge virksomhedsgrudlægger, men drev fortsat Kort tid efter starten skiftede navnet til kameraer hen over zonegrænserne, som Boltaværket I Nürnberg. Der var her, at Photavit for såvel kameraet som for værket . ellers fungerede som landegrænser, hvor der krævedes import og eksport tilladelser. Det gjaldt også leverancer af objektiver og lukkere. Der var gode afsætningsmuligheder i butikker for amerikanske soldater i Tyskland. Alt dette medførte, at Bolta var i gang allerede i 1946, hvor der ellers gik længere tid for nye såvel som gamle tyske producenter. Kameraproduktionen startede op med Photavit med Bolta patronerne og udviklede sig med en modelserie fra III til V. Fra 1952 suppleredes med en produktion af Kameraet har det såkaldte spareformat 24x24 6x6 cm Photina (uægte TLR) og Photina mm på normal 35 mm film . -

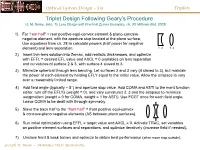

Triplet Design Following Geary's Procedure

Optical System Design – S15 Triplets Triplet Design Following Geary’s Procedure (J. M. Geary, Intro. To Lens Design with Practical Zemax Examples, ch. 30, Willman-Bell, 2002) 1) For “rear half” = rear positive equi-convex element & plano-concave negative element, with the aperture stop located at the plano surface, Use equations from ch. 28 to calculate powers (half power for negative element) and lens separation. 1 2 3 4 2) Insert thin-lens solution into Zemax, add realistic thicknesses, and optimize with EFFL = desired EFL value and AXCL = 0 (variables on lens separation and curvatures of surface 2 & 3, with surface 4 slaved to 3. 3) Minimize spherical through lens bending. Let surfaces 2 and 3 vary (4 slaved to 3), but maintain the power of each element by holding EFLY equal to the initial value. Allow the airspace to vary over a reasonably limited range. 4) Add field angle (typically ~ 5°) and aperture stop value. Add COMA and ASTI to the merit function editor, turn off the EFLYs (weight = 0), and vary curvatures 2, 3 and the airspace to minimize astigmatism (weight = 0 for COMA, weight = 1 for ASTI). Use FCGT once for each field angle. Leave COMA to be dealt with through symmetry. 5) Slave the back half to the “front half” = front positive equi-convex & concave-plano negative elements (AS between plano surfaces). 6) Run initial optimization using EFFL = target value and AXCL = 0. Activate TRAC, set variables on positive-element surfaces and separations, and optimize iteratively (increase field if needed). 7) Unslave front & back halves and optimize to obtain best performance (often move stop outside).