Somalia Security Situation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Action Is Funded by the European Union

EN This action is funded by the European Union ANNEX 7 of the Commission Decision on the financing of the Annual Action Programme 2018 – part 3 in favour of Eastern and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean to be financed from the 11th European Development Fund Action Document for Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) 1. Title/basic act/ Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) CRIS number RSO/FED/040-766 financed under the 11th European Development Fund (EDF) 2. Zone East Africa, Somalia benefiting from The action shall be carried out in Somalia, in the following Federal the Member States (FMS): Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland action/location 3. Programming 11th EDF – Regional Indicative Programme (RIP) for Eastern Africa, document Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean (EA-SA-IO) 2014-2020 4. Sector of Regional economic integration DEV. Aid: YES1 concentration/ thematic area 5. Amounts Total estimated cost: EUR 59 748 500 concerned Total amount of EDF contribution: EUR 42 000 000 This action is co-financed in joint co-financing by: Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) for an amount of EUR 3 500 000 African Development Fund (ADF) 14 Transitional Support Facility (TSF) Pillar 1: EUR 12 309 500 New Partnership for Africa's Development Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (NEPAD-IPPF): EUR 1 939 000 6. Aid Project Modality modality(ies) Indirect management with the African Development Bank (AfDB). and implementation modality(ies) 7 a) DAC code(s) 21010 (Transport Policy and Administrative Management) - 8% 21020 (Road Transport) - 91% b) Main 46002 – African Development Bank (AfDB) Delivery Channel 1 Official Development Aid is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective. -

The Gulf Crisis: the Impasse Between Mogadishu and the Regions 4

ei September-October 2017 Volume 29 Issue 5 The Gulf Engulfing the Horn of Africa? Contents 1. Editor's Note 2. Entre le GCC et l'IGAD, les relations bilatérales priment sur l'aspect régional 3. The Gulf Crisis: The Impasse between Mogadishu and the regions 4. Turkish and UAE Engagement in Horn of Africa and Changing Geo-Politics of the Region 1 Editorial information This publication is produced by the Life & Peace Institute (LPI) with support from the Bread for the World, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and Church of Sweden International Department. The donors are not involved in the production and are not responsible for the contents of the publication. Editorial principles The Horn of Africa Bulletin is a regional policy periodical, monitoring and analysing key peace and security issues in the Horn with a view to inform and provide alternative analysis on on-going debates and generate policy dialogue around matters of conflict transformation and peacebuilding. The material published in HAB represents a variety of sources and does not necessarily express the views of the LPI. Comment policy All comments posted are moderated before publication. Feedback and subscriptions For subscription matters, feedback and suggestions contact LPI’s Horn of Africa Regional Programme at [email protected]. For more LPI publications and resources, please visit: www.life-peace.org/resources/ Life & Peace Institute Kungsängsgatan 17 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden ISSN 2002-1666 About Life & Peace Institute Since its formation, LPI has carried out programmes for conflict transformation in a variety of countries, conducted research, and produced numerous publications on nonviolent conflict transformation and the role of religion in conflict and peacebuilding. -

Somalia Nutrition Cluster

SOMALIA NUTRITION CLUSTER GEDO Sub-National Nutrition Cluster Meeting Minutes (SRDA Dolow Office -17th January 2018 -10:00 – 11:00 am) Agenda Discussions Action points Welcome and As scheduled on 17th January 2018, the Gedo Nutrition Cluster was held at SRDA main Hall Closed Introduction –Dolow Office, the meeting officially opened by Gedo NCCo Mr. Aden Ismail with a word of prayer from Hussein From Trocaire. The meeting was poorly attended Review of the The chair reviewed the previous meeting minute which took place the same venue on 20th Closed previous December 2017 in discussion with the rest of the partners for their confirmation and meeting endorsement an agreed as a true record. minutes and action points Key nutrition The general situation of the region is discussed regarding the drought situation in the region services and which is almost rescaling up again as the rain performed poorly most of the District which situation didn’t left any impact for already devastating ago-pastoralist inhabiting along the Juba river, highlights this resulted internal movement between an area which had received less rain performance to a better place, hence leaving the fragile Women and Children behind to take look after the domestic livestock. Generally the Malnutrition rate across the region reported stable and decreased Mr. Burale from UNOCHA who usually attend the cluster emphasized the important of coordination’s at District level specially agencies implementing programs with the some district. Internal Coordination Between HIRDA, AMA and Trocaire at Bula Hawa District has been conducted in the presence of Aden Ismail NCco and Mr Abdirizak DMO beledhawa District, to address referral challenges. -

Fact Sheet V4

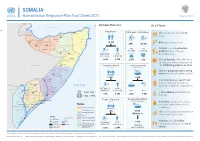

SOMALIA Humanitarian Response Plan Fact Sheet 2021 February 2021 Somalia Overview At a Glance p p! G U L F O F A D E N Caluula Lorem ipsum !p ! Qandala D J I B O U T I Zeylac !p! p Population !pLaasqoray Refugees Returnees Bossaso 69% live on less than $1.90 Awdal ! Ceerigaabo p Lughaye !!p p p a day p! pp Berbera p ! Baki Sanaag ! Iskushuban Borama Woqooyi Ceel Afweyn !! Galbeed !p Sheikh ! Bari p 12.3M Gebiley 40% adult literacy rate p ! p p p Bandarbayla 28K 109.9K !!p !p p ! Odweyne ! Burco ! Qardho pp! ! Hargeysa p Xudun ! !Taleex p Caynabo !p #OF 10,300 recorded protection Togdheer Sool p #OF IDP SITES Laas Caanood PARTNERS incidents from January- p! ! !p p Buuhoodle ! ! Garowe p INTERNALLY NON- December 2020 p p ! DISPLACED DISPLACED Eyl Nugaal ! Burtinle 2.6M 9.7M 2,472 363 20% of Somalis will suffer from !Jariiban ! Galdogob the direct or indirect impacts of Gaalkacyo E T H I O P I A !!p People in Need Food insecurity the COVID19 pandemic in 2021 (2021) (Jan-Jun 2021) ! ! Cadaado Mudug p Cabudwaaq 182,000 pregnant and lactating Dhuusamarreeb !! p women are acutely malnourished Hobyo Galgaduud p ! pp p 5.9M 2.6M p ! Belet Weyne Ceel Buur Ceel Barde !p! Xarardheere ! ! ! 1 in 1,000 women aged 15-49 ! Hiraan p Yeed years in Somalia dies due to ! Bakool Xudur p !!p Doolow ! Ceel Dheer Indian Ocean Bulo Burto pregnancy-related complications Luuq Tayeeglow ! ! ! p! ! Waajid !Adan Yabaal Belet Xaawo p NON- p INTERNALLY K E N Y A Garbahaarey Jalalaqsi !! ! DISPLACED DISPLACED IPC3 IPC4 !Berdale Baidoa Middle ! Gedo !p p Shabelle 2021 -

Somalia Puntland-Constitution Dec2009

CONSTITUTION OF PUNTLAND STATE OF SOMALIA December 2009 National Democratic Institute (NDI) unofficial translation into English of the 2009 Constitution of Puntland State of Somalia. NDI accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of this translation. Any errors or inconsistencies that may exist in the original Somali were translated into English. The Somali version remains authoritative. Puntland State was created in 1998 through a consultative agreement among the different regions that constitute Puntland. The creation of Puntland State emerged from Somalia’s failure to re-establish an inclusive national government for eight years. The people of Puntland realized they could not continue without a government. It was then decided in the constitutional conference of 1998 that Puntland would become a state that would be part of a federal Somalia. A charter was approved in that same 1998 conference and later replaced with a provisional constitution that was approved by members of the House of Representatives in 2001. A referendum on the constitution was to have taken place in 2004, although this was not accomplished. Since it was not possible to hold a referendum on the constitution it was decided that the constitution would continue in force while undergoing review. The constitutional review process began in May 2007 and continued until June 2009. In the review process, meaningful opinions were contributed from different sectors of Puntland society, such as Somali lawyers and foreign lawyers. Therefore, the new constitution was drafted to become the law of the people of Puntland and was based on the Islamic shari’a and, at the same time, the constitution guides the system of governance, and thus brings collaboration and order among the different government institutions of the state. -

Somalian Turvallisuustilanne 28.6.2016

1 (42) MUISTIO MIG-168269 06.03.00 MIGDno-2016-706 28.06.2016 SOMALIAN TURVALLISUUSTILANNE KESÄKUUSSA 2016 Sisällysluettelo 1. Yleiset turvallisuusolosuhteet ...................................................................................... 2 2. Konfliktin vaikutukset siviiliväestöön ............................................................................ 7 3. Turvallisuustilanne alueittain tammi - toukokuussa 2016 ........................................... 10 3.1. Lower Jubba ............................................................................................................. 11 3.2. Gedo ......................................................................................................................... 12 3.3. Bay ............................................................................................................................ 14 3.4. Bakool ....................................................................................................................... 15 3.5. Middle Jubba ............................................................................................................. 15 3.6. Lower Shabelle ......................................................................................................... 15 3.7. Benadir - Mogadishu ................................................................................................. 18 3.8. Middle Shabelle ......................................................................................................... 22 3.9. Hiiraan ..................................................................................................................... -

Emergency Appeal Operations Update Somalia: Tropical Cyclone

Emergency appeal operations update Somalia: Tropical cyclone Emergency appeal n° MDRSO002 GLIDE n° TC – 2013-000140-SOM Operations update n° 2 Timeframe covered by this update: 10 January 2014 – 5 February 2014 Emergency Appeal operation start date: 20 Timeframe: 9 months and end date September 2014 December 2013 Appeal budget: CHF Appeal coverage: Total estimated Red Cross and Red Crescent 2,406,038 18 % response to date: CHF 426,817 Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) allocated: 67,841 N° of people being assisted: 23,100 (3,300 households) Host National Society presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): 50 volunteers, 40 staff and 2 SRCS Branches (Garowe and Bosaso) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS), IFRC, ICRC Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: WFP,UNICEF,UNHCR,FAO,UNFPA, World Vision, CARE, NRC, DRC, IOM, FINAID, ADESO Summary: On Sunday 10 November 2013, the State of Puntland was hit by a tropical cyclone, followed by very heavy rains and flash floods. The cyclone caused loss of human lives and the destruction of assets including livestock and fishing boats, destroyed numerous settlements, service centers, roads, schools, communication and electrical installations. The most affected areas included, Dangorayo, Bandar Beyla, Garowe and Eyl districts. Other areas affected include the coastal villages in Bari region including Hafun, Iskushuban, Bargal, Qandala and Allula districts. With the support of IFRC and the start-up loan provided through the DREF operation, the Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS) undertook a detailed assessment in the affected areas in Nugaal and Bari regions. -

Somalia: Al-Shabaab – It Will Be a Long War

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°99 Nairobi/Brussels, 26 June 2014 Somalia: Al-Shabaab – It Will Be a Long War I. Overview Despite the recent military surge against Somalia’s armed Islamist extremist and self- declared al-Qaeda affiliate, Al-Shabaab, its conclusive “defeat” remains elusive. The most likely scenario – already in evidence – is that its armed units will retreat to small- er, remote and rural enclaves, exploiting entrenched and ever-changing clan-based competition; at the same time, other groups of radicalised and well-trained individ- uals will continue to carry out assassinations and terrorist attacks in urban areas, in- cluding increasingly in neighbouring countries, especially Kenya. The long connec- tion between Al-Shabaab’s current leadership and al-Qaeda is likely to strengthen. A critical breakthrough in the fight against the group cannot, therefore, be achieved by force of arms, even less so when it is foreign militaries, not the Somali National Army (SNA), that are in the lead. A more politically-focused approach is required. Even as its territory is squeezed in the medium term, Al-Shabaab will continue to control both money and minds. It has the advantage of at least three decades of Salafi-Wahhabi proselytisation (daawa) in Somalia; social conservatism is already strongly entrenched – including in Somaliland and among Somali minorities in neigh- bouring states – giving it deep reservoirs of fiscal and ideological support, even with- out the intimidation it routinely employs. An additional factor is the group’s proven ability to adapt, militarily and politically – flexibility that is assisted by its leadership’s freedom from direct accountability to any single constituency. -

Somalia Terror Threat

THECHRISTOPHER TERROR February 12, THREAT FROM THE TERROR THREAT FROM SOMALIA THE INTERNATIONALIZATION OF AL SHABAAB CHRISTOPHER HARNISCH APPENDICES AND MAPS BY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN FEBRUARY 12, 2010 A REPORT BY THE CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE THE TERROR THREAT FROM SOMALIA CHRISTOPHER HARNISCH February 12, 2010 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 IMPORTANT GROUPS AND ORGANIZATIONS IN SOMALIA 3 NOTABLE INDIVIDUALS 4 INTRODUCTION 8 ORIGINS OF AL SHABAAB 10 GAINING CONTROL, GOVERNING, AND MAINTAINING CONTROL 14 AL SHABAAB’S RELATIONSHIP WITH AL QAEDA, THE GLOBAL JIHAD MOVEMENT, AND ITS GLOBAL IDEOLOGY 19 INTERNATIONAL RECRUITING AND ITS IMPACT 29 AL SHABAAB’S INTERNATIONAL THREATS 33 THREAT ASSESSMENT AND CONCLUSION 35 APPENDIX A: TIMELINE OF MAJOR SECURITY EVENTS IN SOMALIA 37 APPENDIX B: MAJOR SUICIDE ATTACKS AND ASSASSINATIONS CLAIMED BY OR ATTRIBUTED TO AL SHABAAB 47 NOTES 51 Maps MAP OF THE HORN OF AFRICA AND MIDDLE EAST 5 POLITICAL MAP OF SOMALIA 6 MAP OF ISLAMIST-CONTROLLED AND INFLUENCED AREAS IN SOMALIA 7 www.criticalthreats.org THE TERROR THREAT FROM SOMALIA CHRISTOPHER HARNISCH February 12, 2010 Executive Summary hree hundred people nearly died in the skies of and assassinations. Al Shabaab’s primary objectives at TMichigan on Christmas Day, 2009 when a Niger- the time of the Ethiopian invasion appeared to be ian terrorist attempted to blow up a plane destined geographically limited to Somalia, and perhaps the for Detroit. The terrorist was an operative of an al Horn of Africa. The group’s rhetoric and behavior, Qaeda franchise based in Yemen called al Qaeda in however, have shifted over the past two years reflect- the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). -

SOMALIA Food Security Outlook October 2018 to May 2019

SOMALIA Food Security Outlook October 2018 to May 2019 Deyr rainfall expected to sustain current outcomes, except in some pastoral areas KEY MESSAGES Current food security outcomes, October 2018 • Food security has continued to improve throughout Somalia since the 2018 Gu. Most northern and central livelihood zones are Stressed (IPC Phase 2), while southern livelihood zones are Minimal (IPC Phase 1) or Stressed (IPC Phase 2). In October, humanitarian assistance continued to prevent worse outcomes in Guban Pastoral and northwestern Northern Inland Pastoral (NIP) livelihood zones, where Crisis! (IPC Phase 3!) and Stressed! (IPC Phase 2!) outcomes persist, respectively. Northwest Agropastoral and most IDP settlements are also in Crisis (IPC Phase 3). • Contrary to earlier forecasts, Deyr seasonal rainfall is now expected to be below-average despite the development of a weak El Niño. Overall, favorable soil moisture is anticipated to prevent large declines in Deyr crop production and rangeland resources, and current outcomes are likely to be sustained in most livelihood zones through May 2019. In Addun Pastoral, Coastal Deeh Pastoral and Fishing, and northeastern NIP livelihood zones, however, deterioration in pasture and water resources is likely to lead to Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes during Source: FEWS NET and FSNAU FEWS NET and FSNAU classification is IPC-compatible. IPC- the 2019 pastoral lean season. compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but does not necessarily reflect a consensus of national food security partners. • In the absence of food assistance, deterioration to Emergency (IPC Phase 4) in Guban Pastoral livelihood zone and to Crisis (IPC Phase 3) in northwestern NIP livelihood zone is likely. -

Ground: Its History, Complexities, Threats and Implementation

PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS FOR THE PEACEKEEPER ON THE GROUND: ITS HISTORY, COMPLEXITIES, THREATS AND IMPLEMENTATION BY Eric Rudberg A THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL COMPLETION OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF The Certificate of Training in United Nations Peace Support Operations Peace Operations Training Institute® Index Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………1 Background to Protection of Civilians (PoC) in Armed Conflict…………………………2 Why Protect Civilians?........................................................................................................5 Right to Self-Defense…………………………………………………………………….10 Defining a “Civilian”…………………………………………………………………….12 Common Threats to Civilians……………………………………………………………16 o Torture or Other Prohibited Treatment……………………………………..……17 o Gender Based and Sexual Violence……...……………………………………....18 o Violence Against Children (Six Grave Violation Against Children)………………………..…..…….....21 . Killing & Maiming……………………………………………………....21 . Recruitment and/or Use of Child Soldiers…………………………….....22 . Sexual Violence………………………………………………………….24 . Attacks Against Schools & Hospitals…………………………………....25 . Denial of Humanitarian Access………………………………………….26 . Abduction…………………………………………………………….......27 o Human Trafficking…………………………………………………………….....28 o Forced Displacement………………………………………………………..…...29 o Denial of Humanitarian Assistance……………………………………………...30 o Explosive Weapons………………………………………………………….…...31 o Peacekeepers………………………………………………………………..…....32 Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) for Reducing Threats to Civilians…………………………………………………....34 -

Constitution of the Puntland State of Somalia

CONSTITUTION OF THE PUNTLAND STATE OF SOMALIA December 2009 English Translation November 2011 .• Puntland State was created in 1998 through a consultative agreement among the different regions that constitute Puntland. The creation of Puntland State emerged from Somalia's failure to re-establish an inclusive national government for eight years. The people of Puntland realized they could not continue without a government. It was then decided in the constitutional conference of 1998 that Punt land would become a state that would be part of a federal Somalia. A charter was approved in that same 1998 conference and later replaced with a provisional constitution that was approved by members of the House of Representatives in 200 l. A referendum on the constitution was to have taken place in 2004, although this was not accomplished. Since it was not possible to hold a referendum on the constitution it was decided that the constitution would continue in force while undergoing review. The constitutional review process began in May 2007 and continued until June 2009. In the review process, meaningful opinions were contributed from different sectors of Puntland society, such as Somali lawyers and foreign lawyers. Therefore, the new constitution was drafted to become the law of the people of Puntland and was based on the Islamic shari'a and, at the same time, the constitution guides the system of governance, and thus brings collaboration and order among the different government institutions of the state. It is important to mention that this constitution will have an impact on the life of every Puntlander, because no nation may exist without laws, and therefore this constitution brings order among citizens and moreover entrenches their human rights and responsibilities so that they may attain social and economic development.