Depiction of Nature in the Sculptural Art of Early Deccan (Up to 10Th Century Ad)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of State-Wise National Parks & Wildlife Sanctuaries in India

List of State-wise National Parks & Wildlife Sanctuaries in India Andaman and Nicobar Islands Sr. No Name Category 1 Barren Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 2 Battimalve Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 3 Bluff Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 4 Bondoville Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 5 Buchaan Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 6 Campbell Bay National Park National Park 7 Cinque Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 8 Defense Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 9 East Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 10 East Tingling Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 11 Flat Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 12 Galathea National Park National Park 13 Interview Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 14 James Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 15 Kyd Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 16 Landfall Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 17 Lohabarrack Salt Water Crocodile Sanctuary Crocodile Sanctuary 18 Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park National Park 19 Middle Button Island National Park National Park 20 Mount Harriet National Park National Park 21 Narcondum Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 22 North Button Island National Park National Park 23 North Reef Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 24 Paget Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 25 Pitman Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 26 Point Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 27 Ranger Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Download Book

The Indian Institute of Culture Basavangudi, Bangalore Transaction No/io YANTRAS OR MECHANICAL B CONTRIVANCES IN ANCIENT INDIA? otoio By V. RAGHAVAN, M.A.,PH.D. =3 (EJggj £53 !2S2» February 1952 Prjce: Re. 1/8 )<93 /dZ^J TJ/ THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF CULTURE TRANSACTIONS YANTRAS OR MECHANICAL ' Many valuable lectures are given, papers read and discussed, and oral CONTRIVANCES IN ANCIENT INDIA-'.. reviews of outstanding books presented, at the Indian Institute of Culture. Its day is still one of small beginnings, but wider dissemination of at least a few of " To deny to Babylon, to Egypt and to India, their part in the development these addresses and papers is obviously in the interest of the better intercultural of science and scientific thinking is to defy the testimony of the ancients, supported understanding so important for world peace. Some of these are published in the by the discovery of the modem authorities." L. C. KARPINSKI. * Institute's monthly organ, The Aryan Path; then we have two series of occa " Thus we see that India's marvels were not always false." LYNN sional papers—Reprints from that journal, and Transactions. The Institute is not responsible fox* views expressed and does not necessarily concur in them. TlIORNDIKE. 2 , Transaction No. 10 : It is indeed in the realms of literature and art, religion and philosophy Dr. V. Raghavan heads the Department of Sanskrit in the University of that ancient India made its outstanding contributions. While the achievements Madras. He came to Bangalore to deliver two lectures, on June 18th and 19th, in the former have gained world-wide appreciation, those in the latter constitute 1951, under the auspices of the Indian Institute of Culture. -

Dharma Dogs: a Narrative Approach to Understanding the Connection of Sentience Between Humans and Canines Anna Caldwell SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Dharma Dogs: A Narrative Approach to Understanding the Connection of Sentience Between Humans and Canines Anna Caldwell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Community-Based Learning Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Caldwell, Anna, "Dharma Dogs: A Narrative Approach to Understanding the Connection of Sentience Between Humans and Canines" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2500. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2500 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dharma Dogs A Narrative Approach to Understanding the Connection of Sentience Between Humans and Canines Cadwell, Anna Academic Director: Decleer, Hubert and Yonetti, Eben Franklin and Marshall College Anthropology Central Asia, India, Himachal Pradesh, Dharamsala Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Nepal: Tibetan and Himalayan Peoples, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2016 Abstract India has the highest population of stray dogs in the world1. Dharamsala, a cross-cultural community in the north Indian Himalayan foothills, is home to a number of particularly overweight and happy canines. However, the street dogs of Dharamsala are not an accurate representation of the state of stay dogs across India. -

Government of India Ministry of Tourism

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.3341 ANSWERED ON 09.08.2021 SETTING UP OF TOURISM HUBS 3341. PROF. SOUGATA RAY: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has any proposal to set up tourism hubs in the country; (b) if so, the details thereof, State-wise; and (c) the details of existing pilgrim tourism hubs in the country? ANSWER MINISTER OF TOURISM (SHRI G. KISHAN REDDY) (a) to (c): Development and promotion of Tourism is primarily the responsibility of the State Government / Union Territory Administration. The Ministry of Tourism, under its ‘Swadesh Darshan scheme’ is developing thematic circuits in the country in planned and prioritized manner in order to develop tourism infrastructure at multiple destinations. The Ministry under its scheme ‘National Mission on Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual, Heritage Augmentation Drive (PRASHAD)’ provides financial assistance to State Governments/ Union Territory (UT) Administrations etc. with the objective of integrated development of identified pilgrimage and heritage destinations. Sanctioning of the projects is a continuous process and is subject to availability of funds, submission of suitable Detailed Project Reports, adherence to scheme guidelines and utilization of funds released earlier etc. The details of projects sanctioned under ‘Swadesh Darshan’ and ‘PRASHAD’ scheme are annexed. ******* ANNEXURE STATEMENT IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) TO (c) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3341 ANSWERED ON 09.08.2021 REGARDING SETTING UP OF TOURISM HUBS. I. THE DETAILS OF PROJECTS SANCTIONED UNDER SWADESH DARSHAN SCHEME (Rs. in crore) Sl. State/UT Name of the Name of the Project Amount No. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

A List of Terminated Vendors As on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner

A List of Terminated Vendors as on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner Name Address City Reason for Termination 1 124475 Excel Associates 123 Infocity Mall 1 Infocity Gandhinagar Sarkhej Highway , Gandhinagar Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 2 125073 Karnavati Associates 303, Jeet Complex, Nr.Girish Cold Drink, Off.C.G.Road, Navrangpura Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 3 132097 Sam Agency 29, 1St Floor, K B Commercial Center, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380001 Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 4 124284 Raza Enterprises Shopno 2 Hira Mohan Sankul Near Bus Stand Pimpalgaon Basvant Taluka Niphad District Nashik Ahmednagar Fraud Termination 5 124306 Shri Navdurga Services Millennium Tower Bldg No. A/5 Th Flra-201 Atharva Bldg Near S.T Stand Brahmin Ali, Alibag Dist Raigad 402201. Alibag Breach Of Contract 6 131095 Sharma Associates 655,Kot Atma Singh,B/S P.O. Hide Market, Amritsar Amritsar Breach Of Contract 7 124227 Aarambh Enterprises Shop.No 24, Jethliya Towars,Gulmandi, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 8 124231 Majestic Enterprises Shop .No.3, Khaled Tower,Kat Kat Gate, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 9 125094 Chudamani Multiservices Plot No.16, """"Vijayottam Niwas"" Aurangabad Breach Of Contract 10 NA Aditya Solutions No.2239/B,9Th Main, E Block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, Karnataka -560010 Bangalore Fraud Termination 11 125608 Sgv Associates #90/3 Mask Road,Opp.Uco Bank,Frazer Town,Bangalore Bangalore Fraud Termination 12 130755 C.S Enterprises #31, 5Th A Cross, 3Rd Block, Nandini Layout, Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 13 NA Sanforce 3/3, 66Th Cross,5Th Block, Rajajinagar,Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 14 132890 Manasa Enterprises No-237, 2Nd Floor, 5Th Main First Stage, Khb Colony, Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079 Bangalore Breach Of Contract 15 177367 Bharat Associates 243 Shivbihar Colony Near Arjun Ki Dairy Bankhana Bareilly Bareilly Breach Of Contract 16 132878 Nuton Smarte Service 102, Yogiraj Apt, 45/B,Nutan Bharat Society,Opp. -

Adaptation and Invention During the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China

Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation D'Alpoim Guedes, Jade. 2013. Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11002762 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China A dissertation presented by Jade D’Alpoim Guedes to The Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Anthropology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2013 © 2013 – Jade D‘Alpoim Guedes All rights reserved Professor Rowan Flad (Advisor) Jade D’Alpoim Guedes Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China Abstract The spread of an agricultural lifestyle played a crucial role in the development of social complexity and in defining trajectories of human history. This dissertation presents the results of research into how agricultural strategies were modified during the spread of agriculture into Southwest China. By incorporating advances from the fields of plant biology and ecological niche modeling into archaeological research, this dissertation addresses how humans adapted their agricultural strategies or invented appropriate technologies to deal with the challenges presented by the myriad of ecological niches in southwest China. -

Lion Symbol in Hindu-Buddhist Sociological Art and Architecture of Bangladesh: an Analysis

International Journal in Management and Social Science Volume 08 Issue 07, July 2020 ISSN: 2321-1784 Impact Factor: 6.178 Journal Homepage: http://ijmr.net.in, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal Lion Symbol in Hindu-Buddhist Sociological Art and Architecture of Bangladesh: An Analysis Sk. Zohirul Islam1, Md. Kohinoor Hossain2, Mst. Shamsun Naher3 Abstract There is no lion animal in Bangladesh still live but has a lot of sculptors through terracotta art in architecture, which are specially used as decorative as religious aspects through the ages. The lion is the king of the animal world. They live in the plain and grassy hills particularly. Due to these characteristics, the lion has been considered through all ages in the world as a symbol of royalty and protection as well as of wisdom and pride, especially in Hindu- Buddhist religion. In Buddhism, lions are symbolic of the Bodhisattvas. In Buddhist architecture, lion symbols are used as protectors of Dharma and therefore support the throne of the Buddha’s and Bodhisattvas. The lion symbol is also used in Hindu temple architecture as Jora Shiva Temple, Akhrapara Mondir of Jashore. In Bangladesh, there are various types of lion symbol used in terracotta plaques of Ananda Vihara, Rupbhan Mura, and Shalban Vihara at Mainamati in Comilla district, Vashu Vihara, Mankalir Kundo at Mahasthangarh in Bogra district and Somapura Mahavihara at Paharpur in Naogaon district. This research has been trying to find out the cultural significance of the lion symbol in Hindu-Buddhist art and architecture of Bangladesh. -

Reiko Ohnuma Animal Doubles of the Buddha

H U M a N I M A L I A 7:2 Reiko Ohnuma Animal Doubles of the Buddh a The life-story of the Buddha, as related in traditional Buddha-biographies from India, has served as a masterful founding narrative for the religion as a whole, and an inexhaustible mine of images and concepts that have had deep reverberations throughout the Buddhist tradition. The basic story is well-known: The Buddha — who should properly be referred to as a bodhisattva (or “awakening-being”) until the moment when he attains awakening and becomes a buddha — is born into the world as a human prince named Prince Siddhārtha. He spends his youth in wealth, luxury, and ignorance, surrounded by hedonistic pleasures, and marries a beautiful princess named Yaśodharā, with whom he has a son. It is only at the age of twenty-nine that Prince Siddhārtha, through a series of dramatic events, comes to realize that all sentient beings are inevitably afflicted by old age, disease, death, and the perpetual suffering of samsara, the endless cycle of death-and-rebirth that characterizes the Buddhist universe. In response to this profound realization, he renounces his worldly life as a pampered prince and “goes forth from home into homelessness” (as the common Buddhist phrase describes it) to become a wandering ascetic. Six years later, while meditating under a fig tree (later known as the Bodhi Tree or Tree of Awakening), he succeeds in discovering a path to the elimination of all suffering — the ultimate Buddhist goal of nirvana — and thereby becomes the Buddha (the “Awakened One”). -

Killing Snakes in Medieval Chinese Buddhism

religions Article The Road to Redemption: Killing Snakes in Medieval Chinese Buddhism Huaiyu Chen 1,2 1 Research Institute of the Yellow River Civilization and Sustainable Development, Henan University, Kaifeng 10085, China; [email protected] 2 School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA Received: 11 March 2019; Accepted: 31 March 2019; Published: 4 April 2019 Abstract: In the medieval Chinese context, snakes and tigers were viewed as two dominant, threatening animals in swamps and mountains. The animal-human confrontation increased with the expansion of human communities to the wilderness. Medieval Chinese Buddhists developed new discourses, strategies, rituals, and narratives to handle the snake issue that threatened both Buddhist and local communities. These new discourses, strategies, rituals, and narratives were shaped by four conflicts between humans and animals, between canonical rules and local justifications, between male monks and feminized snakes, and between organized religions and local cultic practice. Although early Buddhist monastic doctrines and disciplines prevented Buddhists from killing snakes, medieval Chinese Buddhists developed narratives and rituals for killing snakes for responding to the challenges from the discourses of feminizing and demonizing snakes as well as the competition from Daoism. In medieval China, both Buddhism and Daoism mobilized snakes as their weapons to protect their monastic property against the invasion from each other. This study aims to shed new light on the religious and socio-cultural implications of the evolving attitudes toward snakes and the methods of handling snakes in medieval Chinese Buddhism. Keywords: snakes; Buddhist violence; Buddhist women; local community; religious competition 1. -

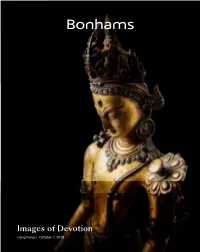

Images of Devotion Hong Kong | October 7, 2019

Images of Devotion Hong Kong | October 7, 2019 Images of Devotion Hong Kong | Monday October 7, 2019 at 6pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES BIDS PHYSICAL CONDITION HONG KONG LTD Indian, Himalayan & Southeast +852 2918 4321 OF LOTS Suite 2001 Asian Art Department +852 2918 4320 fax IN THIS AUCTION PLEASE NOTE One Pacific Place THAT THERE IS NO REFERENCE 88 Queensway Edward Wilkinson To bid via the internet please visit IN THIS CATALOGUE TO THE Admiralty Global Head www.bonhams.com/25283 PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ANY Hong Kong +852 2918 4321 LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS bonhams.com/hongkong [email protected] Please note that telephone bids MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES must be submitted no later than AS TO THE CONDITION OF ANY PREVIEW Mark Rasmussen 4pm on the day prior to the LOTS AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE October 3 Specialist / Head of Sales auction. New bidders must also 15 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS 10am - 7pm +1 (917) 206 1688 provide proof of identity and CONTAINED AT THE END OF October 4 [email protected] address when submitting bids. THIS CATALOGUE. 10am - 7pm October 5 詢問詳情 Please note live online As a courtesy to intending 10am - 7pm 印度、喜馬拉雅及東南亞藝術部門 bidding will not be available bidders, Bonhams provide a October 6 for premium lots: Lot 914 (⁕) written indication of the 10am - 7pm Doris Jin Huang 金夢 physical condition of lots in this October 7 Specialist 請注意,以下拍品將不接受網上 sale if a request is received up 10am - 4pm +1 (917) 206 1620 即時競投:拍品914 (⁕) to 24 hours before the auction [email protected] starts.