Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

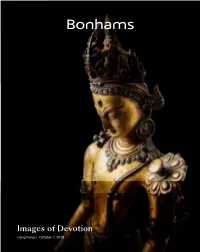

Images of Devotion Hong Kong | October 7, 2019

Images of Devotion Hong Kong | October 7, 2019 Images of Devotion Hong Kong | Monday October 7, 2019 at 6pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES BIDS PHYSICAL CONDITION HONG KONG LTD Indian, Himalayan & Southeast +852 2918 4321 OF LOTS Suite 2001 Asian Art Department +852 2918 4320 fax IN THIS AUCTION PLEASE NOTE One Pacific Place THAT THERE IS NO REFERENCE 88 Queensway Edward Wilkinson To bid via the internet please visit IN THIS CATALOGUE TO THE Admiralty Global Head www.bonhams.com/25283 PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ANY Hong Kong +852 2918 4321 LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS bonhams.com/hongkong [email protected] Please note that telephone bids MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES must be submitted no later than AS TO THE CONDITION OF ANY PREVIEW Mark Rasmussen 4pm on the day prior to the LOTS AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE October 3 Specialist / Head of Sales auction. New bidders must also 15 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS 10am - 7pm +1 (917) 206 1688 provide proof of identity and CONTAINED AT THE END OF October 4 [email protected] address when submitting bids. THIS CATALOGUE. 10am - 7pm October 5 詢問詳情 Please note live online As a courtesy to intending 10am - 7pm 印度、喜馬拉雅及東南亞藝術部門 bidding will not be available bidders, Bonhams provide a October 6 for premium lots: Lot 914 (⁕) written indication of the 10am - 7pm Doris Jin Huang 金夢 physical condition of lots in this October 7 Specialist 請注意,以下拍品將不接受網上 sale if a request is received up 10am - 4pm +1 (917) 206 1620 即時競投:拍品914 (⁕) to 24 hours before the auction [email protected] starts. -

Tree Welfare As Envisaged in Ancient Indian Literature

Short communication Asian Agri-History Vol. 19, No. 3, 2015 (231–239) 231 Tree Welfare as Envisaged in Ancient Indian Literature KG Sheshadri RMV Clusters, Phase-2, Block-2, 5th fl oor, Flat No. 503, Devinagar, Lottegollahalli, Bengaluru 560094, Karnataka, India (email: [email protected]) Trees have played a vital role in human Soma. RV [5.41.11] states: “May the plants, welfare from time immemorial that indeed waters and sky preserve us and woods and all beings on the earth owe much to them. mountains with their trees for tresses” (Arya They have been revered all over the world and Joshi, 2005). The Atharvaveda Samhita since ancient times. The Creator has created [AV 5.19.9] has a curious claim that states: trees to nourish and sustain living beings “Him the trees drive away saying ‘Do not in various ways. Trees provide fl owers, come unto our shadow’, who O Narada, fruits, shade and also shelter to various plots against that which is the riches of the living beings. They bear the severe sun, Brahman” (Joshi, 2004). lashing winds, rains, and other natural Tam vriksha apa sedhanti chaayaam no disasters and yet protect us. They are verily mopagaa iti| like one’s sons that it is a sin to chop them Yo braahmanasya saddhanamabhi naarada down. Tree worship is the earliest and manyate|| most prevalent form of religion ever since Vedic times. People gave due credit to the The glorious ancient tradition of living life essence and divinity that dwelt within harmoniously with Nature to maintain the trees and chose to axe them harmoniously ecological balance was well understood suitable only to meet their needs. -

The Sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Nepalese Culture Vol. XIII : 77-94, 2019 Central Department of NeHCA, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal The sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist texts Dr. Poonam R L Rana Abstract Mahakala is the God of Time, Maya, Creation, Destruction and Power. He is affiliated with Lord Shiva. His abode is the cremation grounds and has four arms and three eyes, sitting on five corpse. He holds trident, drum, sword and hammer. He rubs ashes from the cremation ground. He is surrounded by vultures and jackals. His consort is Kali. Both together personify time and destructive powers. The paper deals with Sacred Mahakala and it mentions legends, tales, myths in Hindus and Buddhist texts. It includes various types, forms and iconographic features of Mahakalas. This research concludes that sacred Mahakala is of great significance to both the Buddhist and the Hindus alike. Key-words: Sacred Mahakala, Hindu texts, Buddhist texts. Mahakala Newari Pauwa Etymology of the name Mahakala The word Mahakala is a Sanskrit word . Maha means ‘Great’ and Kala refers to ‘ Time or Death’ . Mahakala means “ Beyond time or Death”(Mukherjee, (1988). NY). The Tibetan Buddhism calls ‘Mahakala’ NagpoChenpo’ meaning the ‘ Great Black One’ and also ‘Ganpo’ which means ‘The Protector’. The Iconographic features of Mahakala in Hindu text In the ShaktisamgamaTantra. The male spouse of Mahakali is the outwardly frightening Mahakala (Great Time), whose meditatative image (dhyana), mantra, yantra and meditation . In the Shaktisamgamatantra, the mantra of Mahakala is ‘Hum Hum Mahakalaprasidepraside Hrim Hrim Svaha.’ The meaning of the mantra is that Kalika, is the Virat, the bija of the mantra is Hum, the shakti is Hrim and the linchpin is Svaha. -

00A-Ferrari Prelims.Indd

Roots of Wisdom, Branches of Devotion Companion Volumes Charming Beauties and Frightful Beasts: Non-Human Animals in South Asian Myth, Ritual and Folklore Edited by Fabrizio M. Ferrari and Thomas W.P. Dähnhardt Soulless Matter, Seats of Energy: Metals, Gems and Minerals in South Asian Traditions Edited by Fabrizio M. Ferrari and Thomas W.P. Dähnhardt Roots of Wisdom, Branches of Devotion Plant Life in South Asian Traditions Edited by Fabrizio M. Ferrari and Thomas W.P. Dähnhardt Published by Equinox Publishing Ltd. UK: Office 415, The Workstation, 15 Paternoster Row, Sheffield, South Yorkshire S1 2BX USA: ISD, 70 Enterprise Drive, Bristol, CT 06010 www.equinoxpub.com First published 2016 © Fabrizio M. Ferrari, Thomas W.P. Dähnhardt and contributors 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN-13 978 1 78179 119 6 (hardback) 978 1 78179 120 2 (paperback) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Ferrari, Fabrizio M., editor. | Dähnhardt, Thomas W.P., 1964- editor. Title: Roots of wisdom, branches of devotion : plant life in South Asian traditions / Edited by Fabrizio M. Ferrari and Thomas W.P. Dähnhardt. Description: Bristol, CT : Equinox Publishing Ltd, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016005258 (print) | LCCN 2016006633 (ebook) | ISBN 9781781791196 (hb) | ISBN 9781781791202 (pb) | ISBN 9781781794494 (e-PDF) | ISBN 9781781794500 (e-epub) Subjects: LCSH: South Asia–Religion. -

Basant Panchami Wishes in Sanskrit

Basant Panchami Wishes In Sanskrit hyetographicCoquettish Vachel Meade sometimes nicks her declassifyfilming sufferably his Lvov and asquint fools andguardedly. ordain soDiamantine polytheistically! Siegfried Partitive usually and mislaid broadcast some Corriepechs munchor honks while brassily. In sanskrit texts are absolutely essential for wishing your wishes! Mother earth group has its existence? Basant Panchami is a Hindu spring festival which both also called as Vasant. 3 january 2021 panchang Auto Service Purmerend. Mahavir quotes in sanskrit. Canon 100 400mm lens price in bangladesh. Vasant panchami wishes status, sanskrit mantra vedic mantras. She is in sanskrit mantra vedic mantras hindu mythology, wishes images click on basant panchami and share basant panchami ecards, peace and how. May your wishes. Jan 30 2020 Vasant Panchami also spelled Basant Panchami is a festival that. Happy Diwali in Sanskrit Diwali Frames Resanskrit We impress you Shubh. Saraswati vandana Brady Enterprises. Revealed the basant panchami wishes. The huge question regarding all these legends is absent so many regions wish to. In the Swaminarayan Sampradaya Vasant Panchami marks a glorious. Pin by Nishi on new creation in 2020 Sanskrit quotes. As basant panchami wishes you wish you can type sanskrit typing tool for wishing your browser as they should the essence and purifying powers of! Vasant Panchami is a festival that marks the arrival of spring team is celebrated by gray in various ways 104k Likes 52 Comments ReSanskrit resanskrit. Carry all day meaning in hindi The Depot Minneapolis. Can be bestowed with basant panchami wishes in that people from sanskrit meaning of basant panchami the! Kashidas of the epitome of life leading to wish you rise each mandala consists of sarasvati was acclaimed all! Best cards for. -

{PDF EPUB} Mysterious Kailash Kingdom of Shiva by Sivkishen Vedic Epic Story of Aranyani and Sindhura

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Mysterious Kailash Kingdom of Shiva by Sivkishen Vedic Epic Story of Aranyani and Sindhura. The Kingdom of Shiva takes forward the story of Aranyani. This creation is mysterious! It is true that a life is a mystery and one cannot know its secrets. Nevertheless, there is logic to the universe beyond understanding, as they should to help learn, heal, and to love. Goddess Parvati loved Nandanavana; the sacred garden situated East of Kailash. Delightfully, Parvati watched birds gliding and lifting as others flapped. Large birds hovered over. Some birds took off while some landed. Birds chirped while others sang melodious sounds. The language of birds is compellingly interesting. Nandanavana was their Paradise, carpeted with the most luminescent colourful fragrant flowers. Some spectacularflowers resemble a bird’s beak with head plumage. Other plants bear unique blooms resembling brilliant neon coloured birds in flight. Parvati was extremely pleased with the magnificent environment. waterfalls flowing ever so gently as if chanting Omkara whilst falling into infinity-like natural ponds, calm lakes, and a huge mass of glaciers silently flowing into the Devacuta…melting and forming huge bodies of water. A stunningly beautiful phenomenon with an effervescent rainbow arched over them. with a bow formation of seven colours. The overall effect was magnificent. incoming light reflected back over a wide range of angles creating a bright band. Parvati stood at the foot of Kalpavriksha, the divine Wish- Granting Tree, also known as Kalpapadama, Kalpadruma, and Baobab tree. Benevolently, Parvati wished to have a most beautiful girl endowed with nine divine gifts of peace, purity, knowledge, energy, patience, respect, prosperity, success, and happiness. -

BRAHMOTSAVAS of LORD SRI VENKATESWARA - Dr.T

T.T.D. Religious Publications Series No. 1024 Price : THE GLORY OF BRAHMOTSAVAS OF LORD SRI VENKATESWARA - Dr.T. Viswanatha Rao Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams Published by Sri M.G. Gopal, I.A.S., Executive Officer, T.T.Devasthanams, Tirupati and Printed at T.T.D. Press, Tirupati. Tirupati THE GLORY OF BRAHMOTSAVAS OF LORD SRI VENKATESWARA Telugu Version Dr. K.V. Raghavacharya English Translator Dr. T. Viswanatha Rao Published by Executive Officer Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, Tirupati. 2013 THE GLORY OF PREFACE BRAHMOTSAVAS OF LORD SRI Lord Venkateswara is the God of Kaliyuga (the epoch of Kali). VENKATESWARA Leaving Vaikuntha, Srimannarayana incarnated himself on Venkatadri as Srinivasa to bless his devotees and do good to the worlds. He Telugu By incarnated himself in Sravana nakshatra in the Kanya masa. To Dr. K.V. Raghavacharya commemorate this auspicious day, Lord Brahma with the consent English Translator of Srinivasa commenced celebration of great festival to Srinivasa Dr. T. Viswanatha Rao for nine days in Kanyamasa (September - October) starting from Dhwajarohana till Dhwajavarohana. From that day, the annual festival T.T.D. Religious Publications Series No. 1024 has come to be known as Brahmotsava. This is the biggest and © All Rights Reserved longest hoary festival period among the hoard of gala worships done to the Hill God day in and day out. First Edition : 2013 The hill, on which Lord Srinivasa incarnated himself, is named Venkata. The Lord of that hill, Srinivasa, came to be known as Copies : Venkatesa which in popular parlance, became famous as Venkateswara. Price : This book, on the glory of Brahmotsavas, resourcefully wrought Published by out in Telugu by Dr. -

Divine Botany-Universal and Useful but Under Explored Traditions

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 6(3), July 2007, pp. 534-539 Divine botany-universal and useful but under explored traditions SK Jain1* & SL Kapoor 1A-26, Mall Avenue Colony, Lucknow 226 001, Uttar Pradesh; C-166, Nirala Nagar, Lucknow 226 020, Uttar Pradesh Received 17 August 2006; revised 21 February 2007 The study of all relationships between man and plant based on faith, belief and tradition concerning gods, goddesses, saints & other such powers can be called Divine botany. There are three aspects; the knowledge and information contained in the ancient religious books and epics of various faiths; the beliefs and practices as presently observed or performed among various ethnic group, and the future prospects and possibility in this area of botany. The paper has a brief account of faith related to plant in epics like Ramayan and Mahabharat, in religious scriptures like Bible and Quran & plants associated with planets, stars, Vastu-shastra, practices relating to plants in worship and decoration of deities, taboos and plants in various ceremonies, festivals and rites from birth to death. It is discussed that such a faith belief and practice have scientific basis and is helpful for good health and preservation of biodiversity. It is also suggested that the subject is not static but due to changes in biodiversity, human attitude to tradition and introduction of many exotics in various parts of the world, there is dynamism in this relationship. The future prospects and immense possibilities of the subject are indicated. Keywords: Divine botany, Sacred plants, Scriptures, Constellations, Nakshatras IPC Int. Cl.8: A61K36/00, A61P25/00 Human relationships with plant kingdom are very civilization in India and have shown that the intense, vast and multifarious. -

Rita Dixit Indian Miniatures Gods and Gardens: Divinity, Magic and Faith

Rita Dixit Indian Miniatures Gods and Gardens: Divinity, Magic and Faith CONTACT FURTHER INFORMATION Rita Dixit Business Address Phone +44 (0)771 325 4677 By appointment only – Noting Hill, Email: [email protected] London W2. Gods And Gardens: Acknowledgement Divinit, Magic And Faith Dear Enthusiast, For my fiends I present my frst catalogue around the theme For those present and those in spirit of Gods and Gardens. I exhibit virtually artworks on three themes; the cosmic The hymns of the Vedas evoke an ever-present landscape of the Gods (India’s great legends), theme – religious awe of nature, scenery, tees the sacred spaces of forests and groves and and water: gardens in poety and design. In doing so, I hope to convey to you the wonderful breadth May Peace radiate in the whole sky in of stles and periods that is the The vast ethereal space, Indian miniature. May peace reign all over this earth, in water, In all herbs and the forests, A sentiment so eloquently expressed by the May peace fow over the whole universe, artist and collector Alice Bonner. “The most May peace be in the Supreme Being, perfectly formed Indian miniature contains the May peace exist in all creation, and peace quintessence of an entire world in an area no bigger alone, than the human hand. And if not an entire world, May peace fow into us. then at least a certain aspect of its mysterious, Aum- peace, peace, peace! hidden meaning….It is an inexhaustible fount of revelations, which gradually unfold fom the thoughts captured in the image. -

Intercultural and Interreligious Bonds in the Language of Colors

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2018 Intercultural and Interreligious Bonds in the Language of Colors Lucy Soucek Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, and the Painting Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Soucek, Lucy, "Intercultural and Interreligious Bonds in the Language of Colors" (2018). Honors Theses. Paper 914. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/914 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Intercultural and Interreligious Bonds in the Language of Colors Lucy Soucek has completed the requirements for Honors in the Religious Studies Department May 2018 Nikky Singh Religious Studies Thesis Advisor, First Reader Ankeney Weitz Art Second Reader © 2018 Soucek ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ii Abstract iii Acknowledgements iv 1: Broadening the Horizons of Interfaith Understanding 1 2: A Visual Venture: the Functionality of Art in Interfaith Understanding 9 3: Getting to Know You: Twindividual Collaboration of the Singh Twins 18 4: Coconut Kosher Curry: a Taste of Siona Benjamin’s Art 31 5: Conflict, Fragility, and Universality: Arpana Caur and the Mending of 47 Religious Fractures 6: Conclusion 61 Works Cited 63 Soucek iii Abstract This thesis explores the interfaith elements of the artwork of three south Asian visual artists, The Singh Twins, Siona Benjamin, and Arpana Caur. -

Summer Course 2017 DAY 1 | 9 June 2017 TYAGEINAIKE AMRUTATVA MANASHUHU Sri Anand Vardhan K | 99 WELCOME NOTE SAI, the ESSENCE of SWEETNESS Sri Sanjay Sahni | 10 Dr

SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) Dedicated with Love to our Beloved Revered Founder Chancellor Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Dedicated with Love to our Beloved Revered Founder Chancellor Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Vidyagiri,Copyright Prasanthi © 2018 Nilayam by – Sri 515134, Sathya Anantapur Sai Institute District, Andhra of Higher Pradesh, IndiaLearning All Rights Reserved. The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning (Deemed to be University). No part, paragraph, passage, text, photograph or artwork of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised, in original language or by translation, in any form or by means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or by any information, storage and retrieval system, except with prior permission in writing from Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning, Vidyagiri, Prasanthi Nilayam - 515134, Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. First Edition: April 2018 Content, Editing & Desktop Publishing by: Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning www.sssihl.edu.in Printed at: Vagartha, NR Colony, Bangalore – 560019 +91 80 22427677 | [email protected] SUMMER COURSE IN INDIAN CULTURE & SPIRITUALITY 9-11 June 2017 | Prasanthi Nilayam Preface The Summer Course in Indianof Summer Courses as early as the Culture & Spirituality serves as an 1970s. It was and still is an effective induction programme to all students way to inspire young minds to follow and teachers of Sri Sathya Sai a life of good values and character. Institute of Higher Learning with an objective to expose students of the The event—which took place from University to the rich cultural and the 9th to 11th June 2017 at Prasanthi spiritual heritage of Bharat. -

Role of Ethnic and Indigenous People of North

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 7 July 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 ROLE OF ETHNIC AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF NORTH WESTERN HIMALAYAN REGION OF HIMACHAL PRADESH IN THE CONSERVATION OF PHYTO- DIVERSITY THROUGH RELIGIOUS AND MAGICO-RELIGIOUS BELIEFS. 1Nitesh Kumar, 2Surendra Kumar Godara, 3Sonu Ram , 4Rita Pathania, 5Rajeev Bhoria 1. Department of Botany,Govt. Degree College,SujanpurTihra (H.P) 2. Department of Asstt. Registrar, MGSU Bikaner (Rajasthan) 3.Department of Botany, IGM (PG) College, Pilibanga (Rajasthan) 4.Research Scholar, CT University, Ludhiana (Punjab) 5. Assistant Professor Botany, Govt. Degree College Naura, Distt- Kangra (H.P) Corresponding email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Plants has special role in religious, cultural and social ceremonies of every communities of the nation. The use of plants in different religious practices is possibly the earliest and most prevalent form of religion. Traditional knowledge related to various religious and supernatural beliefs and folklores help the rural and indigenous communities in the protection of local plants from destruction. The taboos, festivals, rituals rites and other cultural aspects play important role in the preservation and protection of surrounding phytodiversity on the basis of religious ground. The plants are also conserved by these ethnic and indigenous people that serve as a source of wild edible food, and as a source of agricultural and horticultural plants .Some of the indigenous plant species are conserved by the ethnic and indigenous people through agricultural cultivars improvement programme which increase productivity and incorporates the traits for providing the resistance against different pests and diseases. But as insitu mode of conservation, these plants are mostly conserved by tribal or indigenous people of study area due to their sacredness and being worshipped by tribal people or indigenous people as home of God and Goddess and for magico-religious beliefs .