Intercultural and Interreligious Bonds in the Language of Colors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LATE RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM in SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 591 17 CH17 P590-623.Qxp 4/12/09 15:24 Page 592

17_CH17_P590-623.qxp 12/10/09 09:24 Page 590 17_CH17_P590-623.qxp 12/10/09 09:25 Page 591 CHAPTER 17 CHAPTER The Late Renaissance and Mannerism in Sixteenth- Century Italy ROMTHEMOMENTTHATMARTINLUTHERPOSTEDHISCHALLENGE to the Roman Catholic Church in Wittenberg in 1517, the political and cultural landscape of Europe began to change. Europe s ostensible religious F unity was fractured as entire regions left the Catholic fold. The great powers of France, Spain, and Germany warred with each other on the Italian peninsula, even as the Turkish expansion into Europe threatened Habsburgs; three years later, Charles V was crowned Holy all. The spiritual challenge of the Reformation and the rise of Roman emperor in Bologna. His presence in Italy had important powerful courts affected Italian artists in this period by changing repercussions: In 1530, he overthrew the reestablished Republic the climate in which they worked and the nature of their patron- of Florence and restored the Medici to power. Cosimo I de age. No single style dominated the sixteenth century in Italy, Medici became duke of Florence in 1537 and grand duke of though all the artists working in what is conventionally called the Tuscany in 1569. Charles also promoted the rule of the Gonzaga Late Renaissance were profoundly affected by the achievements of Mantua and awarded a knighthood to Titian. He and his suc- of the High Renaissance. cessors became avid patrons of Titian, spreading the influence and The authority of the generation of the High Renaissance prestige of Italian Renaissance style throughout Europe. would both challenge and nourish later generations of artists. -

Download Book

The Indian Institute of Culture Basavangudi, Bangalore Transaction No/io YANTRAS OR MECHANICAL B CONTRIVANCES IN ANCIENT INDIA? otoio By V. RAGHAVAN, M.A.,PH.D. =3 (EJggj £53 !2S2» February 1952 Prjce: Re. 1/8 )<93 /dZ^J TJ/ THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF CULTURE TRANSACTIONS YANTRAS OR MECHANICAL ' Many valuable lectures are given, papers read and discussed, and oral CONTRIVANCES IN ANCIENT INDIA-'.. reviews of outstanding books presented, at the Indian Institute of Culture. Its day is still one of small beginnings, but wider dissemination of at least a few of " To deny to Babylon, to Egypt and to India, their part in the development these addresses and papers is obviously in the interest of the better intercultural of science and scientific thinking is to defy the testimony of the ancients, supported understanding so important for world peace. Some of these are published in the by the discovery of the modem authorities." L. C. KARPINSKI. * Institute's monthly organ, The Aryan Path; then we have two series of occa " Thus we see that India's marvels were not always false." LYNN sional papers—Reprints from that journal, and Transactions. The Institute is not responsible fox* views expressed and does not necessarily concur in them. TlIORNDIKE. 2 , Transaction No. 10 : It is indeed in the realms of literature and art, religion and philosophy Dr. V. Raghavan heads the Department of Sanskrit in the University of that ancient India made its outstanding contributions. While the achievements Madras. He came to Bangalore to deliver two lectures, on June 18th and 19th, in the former have gained world-wide appreciation, those in the latter constitute 1951, under the auspices of the Indian Institute of Culture. -

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

M8-M9 EXHIBITION.Qxd

M8 India Abroad April 25, 2008 the magazine ART Tara Sabharwal’s Tree Path. As a student, she sold her work to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum Bridging gaps: or Roopa Singh, political poet, adjunct professor The artist of international political science at Pace University and theater instructor with South Asian Youth Action (both in New York), Erasing Borders 2008 — which is currently showing in FNew York — is a deeply diverse exhibit. “An extremely talks back affirming taste of how creative our Diaspora is,” she says. “From eerie florescent gas masks on Bharat Natyam dancers, to blood-hued mangoes for breakfast, to sari and sex pistol clad Desi women ‘stenciled’ on wallpaper, to a playful piece on the New York City sewer caps inscribed in Forty Diaspora artists express their South Asian identity in the US with the bold: Made In India. This is us bearing witness to our- traveling exhibition, Erasing Borders, reports Arthur J Pais selves, a South Asian Diaspora, spread and alive.” Vijay Kumar, curator for the fifth edition of the Erasing childhood; images from pop culture including Bollywood Borders traveling exhibition, has been watching the films, advertising and fashion; strong social commentary; changing Indian art scene in New York for several decades. traditional miniature painting transformed and used for “There are many new ‘Indian’ galleries in New York and new purposes; calligraphy and script; startling juxtaposi- other cities now, fueled by the new wealth in India and the tions; work trying to ‘find a home’ within the psyche.” booming art market there,” he says. “These galleries most- By the time India and Pakistan celebrated 50 years of ly show work by artists still living in India; occasionally, Independence, the words Desi and Diaspora had become they do exhibit work by Diaspora artists.” commonplace, he continues. -

Exploring the Eucharist with Sacred Art

Exploring the Eucharist with Sacred Art UNIT 5, LESSON 1 Learning Goals Connection to the ӹ The narrative of the Last Supper and Catechism of the the Institution of the Eucharist help us Catholic Church to understand the source and summit ӹ CCC 1337-1344 of our Catholic Faith, the Blessed Sacrament. ӹ The Eucharist is the true Body and Vocabulary Blood of Jesus Christ, who is truly ӹ The Last Supper and substantially present under the ӹ The Eucharist appearances of bread and wine. ӹ The Paschal Mystery ӹ We receive the Eucharist in Holy ӹ Mannerism Communion as spiritual food at each and every Mass. BIBLICAL TOUCHSTONES When the hour came, he took his place at table “You call me ‘teacher’ and ‘master,’ and rightly so, with the apostles. He said to them, “I have eagerly for indeed I am. If I, therefore, the master and desired to eat this Passover with you before I teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to suffer, for, I tell you, I shall not eat it [again] until wash one another’s feet. I have given you a model there is fulfillment in the kingdom of God.” Then to follow, so that as I have done for you, you he took a cup, gave thanks, and said, “Take this should also do.” and share it among yourselves; for I tell you [that] JOHN 13:13-15 from this time on I shall not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.” Then he took the bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which will be given for you; do this in memory of me.” And likewise the cup after they had eaten, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which will be shed for you.” LUKE 22:14-20 237 Lesson Plan Materials ӹ The Last Supper ӹ Christ’s Claims and Commandments ӹ The Scriptural Rosary DAY ONE Warm-Up A. -

Cathedrals and the Last Supper

Cathedrals and the Last Supper Expressive use of the Elements and Principals of Art in the Renaissance and other eras By Marcine Linder The Middle Ages • Occurred from approx. 500’s – 1500’s ce • During the middle ages (that preceded the Renaissance) people in western Europe thought of the Church as the center of their existence, guiding them over the rough road of life to salvation. • During the middle ages, they saw life as preparation for heaven (or hell) • Human observations, were de-emphasized in favour of divine truths from the bible and the religious clergy. Gothic Cathedras from the middle ages The Renaissance • French for “re-birth” • By the beginning of the 15th century (1400’s), people began to rediscover the world around them and realize that they were an important part of the world • This led to an interest in the “here and now” as opposed to strictly the afterlife, hence a re-awakening • The Renaissance is characterized by a philosophical movement called “Humanism” in which man was considered to be “a measure of all things” (taking the focus away from God) Renissance Cathedral: St. Paul’s Renissance Cathedral: painting by De Lorme Renissance Cathedral: Tuscany The Last Supper • Has been interpreted and painted in many ways over the centuries • Both the prevailing ideologies/moods of the times and the medium/media chosen (or available) to painters over the centuries has greatly influenced the paintings they have created • “In the Christian Gospels, the Last Supper was the last meal Jesus shared with his Twelve Apostles and disciples before his death. -

Learning to Trust God's Unseen Hand a Study of Esther Esther 6:113

Learning to Trust God’s Unseen Hand A Study of Esther Esther 6:113 Lesson #8: Always trust the timing of God. Verses 13 The unstated reason for the king’s insomnia was God’s providence. To pass the sleepless night, servants brought the royal annals where Mordecai’s deed of saving the king was 1 read (see 2:19–23). The kings of the great ancient empires always kept annals of their reigns. Apparently the 2 king delighted in hearing the records of his own reign. Verses 46 It is quite odd that Mordecai was on the mind of both Xerxes and Haman, and both had their own opinion as to what should be done to him. Who was right? God was. He knew how to bring the actions of all involved to bring about Glory for His name. I would rather not quote you Romans 8:28, but rather Genesis 12:23. See also John 11:4. Read from Piper, “Brothers, We are Not Professionals,” pp 69. When He was on the cross, He was on His mind. More on this later. Verses 79 Haman was only ultimately concerned with Haman. So when asked of how the King should honor the person whom the King delights, Haman immediately thought of what he would have wanted. Selfish desire nearly always supersedes common sense. Haman had not yet asked about the death sentence for Mordecai because he was so caught up in his own honor. To be given a royal robe previously worn by the king was a sign of great honor and the king’s favor. -

Beyond Limits 2013

Beyond Limits 2013 The only way to discover the limits of the possible is to go beyond them into the impossible. Arthur C. Clarke ooking back in time it was a journey we started with our hearts full of hope and anticipation. It was a dream we dared to dream, and the purity of our intentions saw the light of the day. ‘Beyond Limits’ is an L exhibition-cum-sale of exemplary artworks by talented artists with disabilities. These are talents from all across India who have been blessed with elusive creativity. An initiative by FOD, first introduced in the year 2001, to bring to the world the beauty of art which not just soothes the eyes but touches hearts too. Beyond Limits was conceptualized by FOD to a give platform to this talent to showcase their exclusive artwork, which otherwise looked impossible due to barriers- physical, financial, communicational and attitudinal. This noble thought and work has borne fruit; this exhibition is 10th in ‘Beyond Limits’ series. This year, Beyond Limits has again received record breaking participation with jury finding it extremely difficult to select the works for display. Despite the strict selection carried out, the works of 48 artists have been chosen including one with an intellectual disability. Amongst the selected artists many have been honored with Bachelors and Masters degree in Fine Arts. There are many who are currently pursuing their studies in Fine Arts. A few of the participating artists have years of experience in arts to speak for them while 10 of them are getting first opportunity to showcase their work in Beyond Limits. -

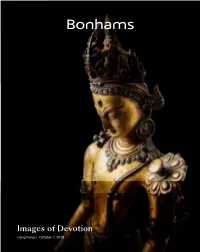

Images of Devotion Hong Kong | October 7, 2019

Images of Devotion Hong Kong | October 7, 2019 Images of Devotion Hong Kong | Monday October 7, 2019 at 6pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES BIDS PHYSICAL CONDITION HONG KONG LTD Indian, Himalayan & Southeast +852 2918 4321 OF LOTS Suite 2001 Asian Art Department +852 2918 4320 fax IN THIS AUCTION PLEASE NOTE One Pacific Place THAT THERE IS NO REFERENCE 88 Queensway Edward Wilkinson To bid via the internet please visit IN THIS CATALOGUE TO THE Admiralty Global Head www.bonhams.com/25283 PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ANY Hong Kong +852 2918 4321 LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS bonhams.com/hongkong [email protected] Please note that telephone bids MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES must be submitted no later than AS TO THE CONDITION OF ANY PREVIEW Mark Rasmussen 4pm on the day prior to the LOTS AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE October 3 Specialist / Head of Sales auction. New bidders must also 15 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS 10am - 7pm +1 (917) 206 1688 provide proof of identity and CONTAINED AT THE END OF October 4 [email protected] address when submitting bids. THIS CATALOGUE. 10am - 7pm October 5 詢問詳情 Please note live online As a courtesy to intending 10am - 7pm 印度、喜馬拉雅及東南亞藝術部門 bidding will not be available bidders, Bonhams provide a October 6 for premium lots: Lot 914 (⁕) written indication of the 10am - 7pm Doris Jin Huang 金夢 physical condition of lots in this October 7 Specialist 請注意,以下拍品將不接受網上 sale if a request is received up 10am - 4pm +1 (917) 206 1620 即時競投:拍品914 (⁕) to 24 hours before the auction [email protected] starts. -

Tree Welfare As Envisaged in Ancient Indian Literature

Short communication Asian Agri-History Vol. 19, No. 3, 2015 (231–239) 231 Tree Welfare as Envisaged in Ancient Indian Literature KG Sheshadri RMV Clusters, Phase-2, Block-2, 5th fl oor, Flat No. 503, Devinagar, Lottegollahalli, Bengaluru 560094, Karnataka, India (email: [email protected]) Trees have played a vital role in human Soma. RV [5.41.11] states: “May the plants, welfare from time immemorial that indeed waters and sky preserve us and woods and all beings on the earth owe much to them. mountains with their trees for tresses” (Arya They have been revered all over the world and Joshi, 2005). The Atharvaveda Samhita since ancient times. The Creator has created [AV 5.19.9] has a curious claim that states: trees to nourish and sustain living beings “Him the trees drive away saying ‘Do not in various ways. Trees provide fl owers, come unto our shadow’, who O Narada, fruits, shade and also shelter to various plots against that which is the riches of the living beings. They bear the severe sun, Brahman” (Joshi, 2004). lashing winds, rains, and other natural Tam vriksha apa sedhanti chaayaam no disasters and yet protect us. They are verily mopagaa iti| like one’s sons that it is a sin to chop them Yo braahmanasya saddhanamabhi naarada down. Tree worship is the earliest and manyate|| most prevalent form of religion ever since Vedic times. People gave due credit to the The glorious ancient tradition of living life essence and divinity that dwelt within harmoniously with Nature to maintain the trees and chose to axe them harmoniously ecological balance was well understood suitable only to meet their needs. -

New Perspectives on American Jewish History

Transnational Traditions Transnational TRADITIONS New Perspectives on American Jewish History Edited by Ava F. Kahn and Adam D. Mendelsohn Wayne State University Press Detroit © 2014 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936561 ISBN 978-0-8143-3861-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-8143-3862-9 (e-book) Permission to excerpt or adapt certain passages from Joan G. Roland, “Negotiating Identity: Being Indian and Jewish in America,” Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies 13 (2013): 23–35 has been granted by Nathan Katz, editor. Excerpts from Joan G. Roland, “Transformation of Indian Identity among Bene Israel in Israel,” in Israel in the Nineties, ed. Fredrick Lazin and Gregory Mahler (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996), 169–93, reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida. CONN TE TS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 PART I An Anglophone Diaspora 1. The Sacrifices of the Isaacs: The Diffusion of New Models of Religious Leadership in the English-Speaking Jewish World 11 Adam D. Mendelsohn 2. Roaming the Rim: How Rabbis, Convicts, and Fortune Seekers Shaped Pacific Coast Jewry 38 Ava F. Kahn 3. Creating Transnational Connections: Australia and California 64 Suzanne D. Rutland PART II From Europe to America and Back Again 4. Currents and Currency: Jewish Immigrant “Bankers” and the Transnational Business of Mass Migration, 1873–1914 87 Rebecca Kobrin 5. A Taste of Freedom: American Yiddish Publications in Imperial Russia 105 Eric L. Goldstein PART III The Immigrant as Transnational 6. -

The Sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Nepalese Culture Vol. XIII : 77-94, 2019 Central Department of NeHCA, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal The sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist texts Dr. Poonam R L Rana Abstract Mahakala is the God of Time, Maya, Creation, Destruction and Power. He is affiliated with Lord Shiva. His abode is the cremation grounds and has four arms and three eyes, sitting on five corpse. He holds trident, drum, sword and hammer. He rubs ashes from the cremation ground. He is surrounded by vultures and jackals. His consort is Kali. Both together personify time and destructive powers. The paper deals with Sacred Mahakala and it mentions legends, tales, myths in Hindus and Buddhist texts. It includes various types, forms and iconographic features of Mahakalas. This research concludes that sacred Mahakala is of great significance to both the Buddhist and the Hindus alike. Key-words: Sacred Mahakala, Hindu texts, Buddhist texts. Mahakala Newari Pauwa Etymology of the name Mahakala The word Mahakala is a Sanskrit word . Maha means ‘Great’ and Kala refers to ‘ Time or Death’ . Mahakala means “ Beyond time or Death”(Mukherjee, (1988). NY). The Tibetan Buddhism calls ‘Mahakala’ NagpoChenpo’ meaning the ‘ Great Black One’ and also ‘Ganpo’ which means ‘The Protector’. The Iconographic features of Mahakala in Hindu text In the ShaktisamgamaTantra. The male spouse of Mahakali is the outwardly frightening Mahakala (Great Time), whose meditatative image (dhyana), mantra, yantra and meditation . In the Shaktisamgamatantra, the mantra of Mahakala is ‘Hum Hum Mahakalaprasidepraside Hrim Hrim Svaha.’ The meaning of the mantra is that Kalika, is the Virat, the bija of the mantra is Hum, the shakti is Hrim and the linchpin is Svaha.