A New Look at Truancy in Chicago's Public High Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

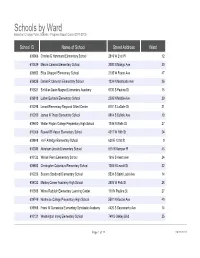

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

Chicago River Schools Network Through the CRSN, Friends of the Chicago River Helps Teachers Use the Chicago River As a Context for Learning and a Setting for Service

Chicago River Schools Network Through the CRSN, Friends of the Chicago River helps teachers use the Chicago River as a context for learning and a setting for service. By connecting the curriculum and students to a naturalc resource rightr in theirs backyard, nlearning takes on new relevance and students discover that their actions can make a difference. We support teachers by offering teacher workshops, one-on-one consultations, and equipment for loan, lessons and assistance on field trips. Through our Adopt A River School program, schools can choose to adopt a site along the Chicago River. They become part of a network of schools working together to monitor and Makingimprove Connections the river. Active Members of the Chicago River Schools Network (2006-2012) City of Chicago Eden Place Nature Center Lincoln Park High School * Roots & Shoots - Jane Goodall Emmet School Linne School Institute ACE Tech. Charter High School Erie Elementary Charter School Little Village/Lawndale Social Rush University Agassiz Elementary Faith in Place Justice High School Salazar Bilingual Education Center Amundsen High School * Farnsworth Locke Elementary School San Miguel School - Gary Comer Ancona School Fermi Elementary Mahalia Jackson School Campus Anti-Cruelty Society Forman High School Marquez Charter School Schurz High School * Arthur Ashe Elementary Funston Elementary Mather High School Second Chance High School Aspira Haugan Middle School Gage Park High School * May Community Academy Shabazz International Charter School Audubon Elementary Galapagos Charter School Mitchell School St. Gall Elementary School Austin High School Galileo Academy Morgan Park Academy St. Ignatius College Prep * Avondale School Gillespie Elementary National Lewis University St. -

Action Civics Showcase

16th annual Action Civics showcase Bridgeport MAY Art Center 10:30AM to 6:30PM 22 2018 DEMOCRACY IS A VERB WELCOME to the 16th annual Mikva Challenge ASPEN TRACK SCHOOLS Mason Elementary Action Civics Aspen Track Sullivan High School Northside College Prep showcase The Aspen Institute and Mikva Challenge have launched a partnership that brings the best of our Juarez Community Academy High School collective youth activism work together in a single This has been an exciting year for Action initiative: The Aspen Track of Mikva Challenge. Curie Metropolitan High School Civics in the city of Chicago. Together, Mikva and Aspen have empowered teams of Chicago high school students to design solutions to CCA Academy High School Association House Over 2,500 youth at some of the most critical issues in their communities. The result? Innovative, relevant, powerful youth-driven High School 70 Chicago high schools completed solutions to catalyze real-world action and impact. Phillips Academy over 100 youth action projects. High School We are delighted to welcome eleven youth teams to Jones College Prep In the pages to follow, you will find brief our Action Civics Showcase this morning to formally Hancock College Prep SCHEDULE descriptions of some of the amazing present their projects before a panel of distinguished Gage Park High School actions students have taken this year. The judges. Judges will evaluate presentations on a variety aspen track work you will see today proves once again of criteria and choose one team to win an all-expenses paid trip to Washington, DC in November to attend the inaugural National Youth Convening, where they will be competition that students not only have a diverse array able to share and learn with other youth leaders from around the country. -

State School Year LEA Name School Name Reading Proficiency Target

Elementary/ Middle School Reading Reading Math Math Other School Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Academic Graduation School Improvement Status for SY State Year LEA Name School Name Target Target Target Target Indicator Rate 2007-08 Illinois 2006-07 EGYPTIAN CUSD 5 EGYPTIAN SR HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 MERIDIAN CUSD 101 MERIDIAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 ROCKFORD SD 205 MCINTOSH SCIENCE AND TECH MAGNET X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 CENTRALIA HSD 200 CENTRALIA HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 MAYWOOD-MELROSE PARK-BROADVIEW 89 LEXINGTON ELEM SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 FOREST PARK SD 91 FOREST PARK MIDDLE SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 POSEN-ROBBINS ESD 143-5 POSEN ELEM SCHOOL X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 SOUTH HOLLAND SD 151 COOLIDGE MIDDLE SCHOOL X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 COUNTRY CLUB HILLS SD 160 MEADOWVIEW SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 OAK PARK - RIVER FOREST SD 200 OAK PARK & RIVER FOREST HIGH SCH X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 MAINE TOWNSHIP HSD 207 MAINE EAST HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 LEYDEN CHSD 212 WEST LEYDEN HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 NILES TWP CHSD 219 NILES NORTH HIGH SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 CITY OF CHICAGO SD 299 CHICAGO DISCOVERY ACADEMY HS X y X y X Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 CITY OF CHICAGO SD 299 PHOENIX MILITARY ACADEMY HS X y X y X -

Chicago Public Schools and the Creation of Global Citizens

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 2017 Chicago Public Schools and the Creation of Global Citizens Rebecca L. Kijek Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Education Policy Commons Recommended Citation Kijek, Rebecca L., "Chicago Public Schools and the Creation of Global Citizens" (2017). Master's Theses. 3685. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3685 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2017 Rebecca L. Kijek LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO CHICAGO PUBLIC SCHOOLS AND THE CREATION OF GLOBAL CITIZENS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS PROGRAM IN CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL POLICY STUDY BY REBECCA KIJEK CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2017 Copyright by Rebecca Kijek, 2017 All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv ABSTRACT v CHAPTER ONE: GLOBALIZATION, SCHOOLS, AND DICHOTOMY 1 CHAPTER TWO: RESEARCH METHODS 11 CHAPTER THREE: FINDINGS 18 CHAPTER FOUR: CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS 39 APPENDIX A: 2016-2017 DEMOGRAPHICS BY SCHOOL AND SCHOOL TYPE 43 APPENDIX B: 2016-2017 COLLEGE ENROLLMENT AND AVERAGE ACT SCORE BY SCHOOL AND SCHOOL TYPE 45 APPENDIX C: 2016-2017 ADVANCED PLACEMENT AND DUAL CREDIT COURSE OFFERINGS BY SCHOOL AND SCHOOL TYPE 47 APPENDIX D: 2016-2017 FOREIGN LANGUAGE OFFERINGS BY SCHOOL AND SCHOOL TYPE 49 APPENDIX E: 2016-2017 EARLY COLLEGE AND CAREER CERTIFICATE BY SCHOOL AND SCHOOL TYPE 51 APPENDIX F: CONSORTIUM OF CHICAGO SCHOOL RESEARCH COLLEGE SELECTIVITY CHART 53 REFERENCES 55 VITA 63 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. -

A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago As Seen in the Naming of Schools

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1990 A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago as Seen in the Naming of Schools Mary McFarland-McPherson Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation McFarland-McPherson, Mary, "A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago as Seen in the Naming of Schools" (1990). Dissertations. 2709. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2709 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1990 Mary McFarland-McPherson A SOCIO-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC EDUCATION IN CHICAGO AS SEEN IN THE NAMING OF SCHOOLS by Mary McFarland-McPherson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 1990 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer sincerely appreciates the patience, · endurance and assistance afforded by the many persons who extended their unselfish support of this dissertation. Special orchids to Dr. Joan K. Smith for her untiring guidance, encouragement, expertise, and directorship. Gratitude is extended to Dr. Gerald L. Gutek and Rev. F. Michael Perko, S.J. who, as members of this committee provided invaluable personal and professional help and advice. The writer is thankful for the words of wisdom and assistance provided by: Mr. -

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2011- 2012 January 29, 2012 Place Score Name 1St 2Nd 3Rd 4Th 5Th 6Th

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2011- 2012 January 29, 2012 Place Score Name 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 1 256.00 Lane Tech High School 3 7 1 2 2 153.50 Bowen High School 3 1 1 2 1 3 87.00 Taft High School 2 1 1 1 4 67.00 Chicago Agi Science 1 1 1 1 5 64.00 King High School 1 1 1 1 6 62.00 Uplift High School 3 1 7 46.00 Northside Prep 2 1 8 45.00 Fenger High School 1 1 9 43.00 Foreman High School 1 1 1 10 42.00 Austin High School 2 1 11 38.00 Kelly High School 1 1 1 12 36.00 Curie High School 2 36.00 Brooks High School 3 14 32.00 Julian High School 1 1 15 30.00 Simeon High School 1 1 16 26.00 Clemente High School 1 26.00 Amundsen High School 1 1 18 24.00 Mather High School 1 24.00 Morgan Park High School 2 20 23.00 Juarez High School 1 1 21 21.00 Kenwood Academy High School 2 22 20.00 Carver High School 1 23 16.00 Douglass High School 2 16.00 Dunbar High School 2 16.00 Hubbard High School 1 26 15.00 Roberson High School 1 1 27 13.00 Manley High School 1 28 11.00 Phoenix Military Academy 1 11.00 Urban Prep High School 1 30 8.00 Gage Park High School 1 31 7.00 Collins High School 1 32 3.00 Team Englewood 3.00 Roosevelt High School 34 2.00 Kennedy High School 35 1.00 Harper High School 1.00 Corliss High School 37 0.00 Al Raby High School 0.00 Farragut High School 0.00 Little Village High School 0.00 Orr High School 0.00 Marshall High School 0.00 Crane High School 0.00 Phillips High School 0.00 Bronzeville 0.00 Bogan High School * Team has non-scoring wrestler Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2011- 2012 January 29, 2012 Place -

Obbp-Final.Pdf

OPEN BOTTLES B R O K E N POLICIES A R E P O R T C R E A T E D B Y V O I C E S O F Y O U T H I N C H I C A G O E D U C A T I O N © 2018 Voices of Youth in Chicago Education. All Rights Reserved. Funding provided in whole or in part by the Strategic Prevention Framework - Partnerships for Success Catalogue of Federal Domestic Assistance No. 93.243, funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration through a grant administered by the Illinois Department of Human Services. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VOYCE WOULD LIKE TO THANK THE FOLLOWING FOR SUPPORTING THIS PROJECT, AND FOR THEIR COMMITMENT TO CENTERING YOUNG PEOPLE’S VOICES IN EFFORTS TO ADDRESS UNDERAGE ALCOHOL USE AND IN CRAFTING SCHOOL POLICY REFORM FOR SAFER AND HEALTHIER LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS. The young people, parents, and community leaders, who participated through surveys and focus groups, for making sure the voices of people most affected by underage alcohol use are at the forefront of advancing systemic changes that will create healthier learning environments in our schools. Jim Freeman for working tirelessly to help VOYCE youth leaders learn from other efforts around ending underage alcohol use across the country. Preventing Alcohol Abuse in Chicago Teens (PAACT) for collaborating with VOYCE in addressing the prevention of alcohol use among 8th through 12th graders in the city of Chicago, and promoting health and wellness where youth are empowered and alcohol free. ANN & ROBERT H. -

FY13 Annual Report

FY13 Annual Report July 1, 2012 – June 30, 2013 A Message from the Co-Founder & CEO Dear Friends, It is with great pleasure that I write to you and provide an organizational update of our progress in fiscal year 2013 (FY13), the 2012-2013 school year. This past year was full of exciting, celebratory moments and it is because of our supporters like you that OneGoal had a successful school year. FY13 marked our first full year of operations in Houston, Texas, our second city of program implementation. Our Chicago- based teachers, called Program Directors, continued to lead our students, called Fellows, to inspiring achievements in classrooms across the city. Beyond this work in high schools, a few of the organization’s highlights included the distinct honor of being featured in How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character, the most recent book written by acclaimed journalist and author Paul Tough. PBS NewsHour also featured a special, nationally-aired segment about Anthony, a OneGoal Fellow from Perspectives Leadership Academy in Chicago now a freshman at Cornell University. Additionally, we were privileged to host the British Secretary of State for Education, the Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, on a visit to a OneGoal-Chicago classroom at Wendell Phillips Academy High School in March 2013. Most importantly in FY13, our OneGoal Fellows continued to achieve at spectacular rates. In a nation where only eight percent of ninth graders from low-income communities graduate from college, 87 percent of OneGoal’s high school graduates have enrolled in college. Of those who enroll, 85 percent are persisting in college or have graduated with a college degree. -

Polling Places Nov

City of Chicago PRELIMINARY List of ELECTION DAY Polling Places Nov. 3, 2020 General Election* (All polling place locations are subject to change.) Ward Prec ELECTION DAY Polling Place & Address ("x" indicates that the polling place is not fully accessible.) 1 1 x Yates School 1826 N Francisco Ave 1 2 x Funston School 2010 N Central Park Ave 1 3 x Wells Community Academy 936 N Ashland Ave 1 4 x Commercial Park 1845 W Rice St 1 5 x LaSalle II Magnet School 1148 N Honore St 1 6 x The Ogden Intrnl H S / Chicago 1250 W Erie St 1 7 x Haas Park 2402 N Washtenaw Ave 1 8 x Wicker Park Senior Housing 2020 W Schiller St 1 9 x The Lincoln Lodge 2040 N Milwaukee Ave 1 10 x LaSalle II Magnet School 1148 N Honore St 1 11 Wicker Pk Fieldhouse 1425 N Damen Ave 1 12 Ukranian Village Cultural Ctr 2247 W Chicago Ave 1 13 x Chase School 2021 N Point St 1 14 x De Diego Community Academy 1313 N Claremont Ave 1 15 x De Diego Community Academy 1313 N Claremont Ave 1 16 x Goethe School 2236 N Rockwell St 1 17 x Funston School 2010 N Central Park Ave 1 18 x Create Your Own Space Studio 937 N Western Ave 1 19 x Chase School 2021 N Point St 1 20 x St Sylvester 2915 W Palmer St 1 21 x LaSalle II Magnet School 1148 N Honore St 1 22 x Wright College 1645 N California Ave 1 23 x St Sylvester 2915 W Palmer St 1 24 x Erie Elementary Charter School 1405 N Washtenaw Ave 1 25 x Erie Elementary Charter School 1405 N Washtenaw Ave 1 26 x Funston School 2010 N Central Park Ave 1 27 x The Joinery 2533 W Homer St 1 28 x Windy City Field House 2367 W Logan Bv 1 29 x Bloomingdale -

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2012-2013 January 27, 2013 Place Score Name 1St 2Nd 3Rd 4Th 5Th 6Th

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2012-2013 January 27, 2013 Place Score Name 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 1 142.50 Bowen High School 1 3 1 3 2 139.50 Lane Tech High School 2 3 1 1 1 3 123.00 Taft High School 3 1 1 1 1 4 65.00 Westinghouse High School 1 2 1 5 47.00 Northside Prep 1 1 6 46.00 Simeon High School 1 1 1 7 45.50 Brooks High School 1 2 8 45.00 Uplift High School 1 2 1 9 43.50 Kelly High School 1 2 10 42.00 Juarez High School 2 11 41.00 Amundsen High School 1 1 12 39.00 Dunbar High School 1 1 2 13 38.00 King High School 1 1 14 37.00 Mather High School 2 15 36.00 Morgan Park High School 1 1 16 33.00 Austin High School 1 1 17 29.00 Kennedy High School 1 1 29.00 Hyde Park High School 1 2 19 28.00 Chicago Agi Science 1 1 20 27.00 Corliss High School 1 1 21 24.00 Lindblom High School 1 22 23.50 Douglass High School 1 23 21.00 Kenwood Academy High School 1 1 24 19.00 Dusable High School 1 25 18.00 Foreman High School 2 18.00 Senn High School 1 27 17.00 Curie High School 1 17.00 Hubbard High School 1 17.00 Carver High School 1 30 9.00 Marshall High School 1 31 8.00 Roberson High School 1 32 7.00 Julian High School 1 7.00 Chicago Vocational Career Academy 1 7.00 Solorio High School 1 35 6.00 Clemente High School 1 36 3.00 Urban Prep High School 37 2.00 Roosevelt High School 2.00 Wahington High School 39 1.00 Bronzeville 1.00 Gary Comer High School 41 0.00 Phoenix Military Academy 0.00 Al Raby High School 0.00 Farragut High School 0.00 Little Village High School 0.00 Orr High School * Team has non-scoring wrestler Chicago Public Schools -

Approved Courses.Xlsx

STEM QL/Stats Technical Partnering College High School Name School District City RCDTS Code (TM001) (TM002) (TM003) Black Hawk College AlWood Middle/High School AlWood CUSD 225 Woodhull 280372250260001 x Black Hawk College Erie High School Erie CUSD 1 Erie 470980010260001 x Black Hawk College Geneseo High School Geneseo CUSD 228 Geneseo 280372280260001 x Black Hawk College Riverdale Senior High School Riverdale CUSD 100 Port Byron 490811000260001 x Black Hawk College Rockridge High School Rockridge CUSD 300 Taylor Ridge 490813000260001 x Black Hawk College United Township Senior High School United Township High School District 30 East Moline 490810300170001 x Black Hawk College Wethersfield Jr/Sr High School Wethersfield CUSD 230 Kewanee 280372300260002 x Carl Sandburg College Knoxville High School Knoxville CUSD 202 Knoxville 330482020260001 x City College Amundsen High School City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250001 x City College Benito Juarez Community Academy City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250767 x City College Bogan High School City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250003 x City College Bronzeville Scholastic High School City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250834 x City College Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250772 x City College Curie Metropolitan High School City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250617 x City College Daniel Hale Williams Preparatory School of Medicine City of Chicago SD 299 Chicago 150162990250856 x City College Dunbar Vocational Career