The Sources of Iranian Negotiating Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sources of Iranian Negotiating Behavior

STR The Sources of Iranian Negotiating Behavior Harold Rhode TEGIC STRAPERSPECTIVES E XECUTIVE SUMMARY This analysis identifies patterns exhibited by the Iranian government and the Iranian people since ancient times. Most importantly, it identifies critical elements of Iranian culture that have been systematically ignored by policymakers for decades. It is a precise understanding of these cultural cues that should guide policy objectives toward the Iranian government. Iranians expect a ruler to demonstrate resolve and strength, and do whatever it takes to remain in power. The Western concept of demanding that a leader subscribe to a moral and ethical code does not resonate with Iranians. Telling Iranians that their ruler is cruel will not convince the public that they need a new leader. To the contrary, this will reinforce the idea that their ruler is strong. It is only when Iranians become convinced that either their rulers lack the resolve to do what is necessary to remain in power or that a stronger power will protect them against their current tyrannical rulers, that they will speak out and try to overthrow leaders. Compromise (as we in the West understand this concept) is seen as a sign of submission and weakness. For Iranians, it actually brings shame on those (and on the families of those) who concede. By contrast, one who forces others to compromise increases his honor and stature, and is likely to continue forcing others to submit in the future. Iranians do not consider weakness a reason to engage an adversary in compromise, but rather as an opportunity to destroy them. -

Turkey by HAROLD RHODE Chapter 2

Ally No More Ally No More Erdoğan’s New Turkish Caliphate and the Rising Jihadist Threat to the West Center for Security Policy Press This book may be reproduced, distributed and transmitted for personal and non-commercial use. Contact the Center for Security Policy for bulk order information. For more information about this book, visit SECUREFREEDOM.ORG Ally No More: Erdoğan’s New Turkish Caliphate and the Rising Jihadist Threat to the West is published in the United States by the Center for Security Policy Press, a division of the Center for Security Policy. ISBN-13: ISBN978-1717071675-10: 1717071678 The Center for Security Policy Washington, D.C. Phone: 202-835-9077 Email: [email protected] For more information, visit SecureFreedom.org Book design by Bravura Books Contents Foreword ................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 5 How to Understand Erdoğan & His Neo-Ottoman Strategy to Destroy Ataturk’s Turkey BY HAROLD RHODE Chapter 2 .................................................................................................. 23 Turkey’s Partnership with the U.S. Muslim Brotherhood BY CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY STAFF Chapter 3 .................................................................................................. 51 Gülen and Erdoğan: Partners on a Brotherhood Mission BY CLARE M. LOPEZ Chapter 4 ................................................................................................. -

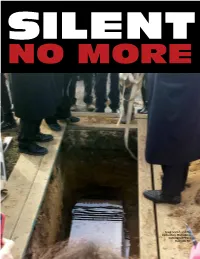

Silent No More

SILENT NO MORE Iraqi jewish archive burial New Montefiore Cemetery in West Babylon, NY IRAQI JEWS SILENT FIGHT FOR THE OWNERSHIP OF THEIR HERITAGE BY MACHLA ABRAMOVITZ he scene at New Montefiore Cemetery in West Babylon, the fragments was negotiated by Maurice Shohet, president of the New York on the wet and chilly afternoon of December World Organization of Iraqi Jews (WOJI). 15 was nothing less than surrealistic. Mingling sociably These, together with thousands of priceless Jewish artifacts res- with over 100 Iraqi Jews who had come from far and cued in 2003 from the flooded basement of Saddam Hussein’s Twide was Lukman Faily, Iraq’s new ambassador to the United intelligence headquarters, had been brought out of Iraq only after States, as well as dignitaries from the Iraqi Ministries of the Inte- an agreement between NARA and Iraq’s interim government was rior, Foreign Affairs and National Security Council who had flown signed, legally binding the US to return the materials to Iraq by in from Baghdad for the occasion. Also attending was US State June 2014. Department Director of Near East and African Affairs Anthony Once in the States, they were lovingly and meticulously Godfrey and Doris Hamburg, Director of the National Archives cleaned, repaired, conserved and digitized by NARA under the and Records Administration preservation program (NARA). They care of Hamburg and Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler, chief of the Docu- had come to bury close to 50 fragments of damaged Torah scrolls ment Conservation Laboratory, at a cost to the State Department and Megillos Esther that were beyond repair and had been part of about $3 million. -

The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation 9 Annual

The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation 9th Annual Conference Friday, April 13, 2018 8:00am-6:30pm Georgetown University Law Center McDonough Hall, Hart Auditorium 600 New Jersey Ave NW, Washington, DC 20001 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Panel 1: Claiming and Disclaiming Ownership: Russian, Ukrainian, both or neither? Panel 2: Whose Property? National Claims versus the Rights of Religious and Ethnic Minorities in the Middle East Panel 3: Protecting Native American Cultural Heritage Panel 4: Best Practices in Acquiring and Collecting Cultural Property Speaker Biographies CLE MATERIALS FOR PANEL 1 Laws/ Regulations Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-confiscated Art (1998) https://www.state.gov/p/eur/rt/hlcst/270431.htm Articles/ Book Chapters/ White Papers Quentin Byrne-Sutton, Arbitration and Mediation in Art-Related Disputes, ARBITRATION INT’L 447 (1998). F. Shyllon, ‘The Rise of Negotiation (ADR) in Restitution, Return and Repatriation of Cultural Property: Moral Pressure and Power Pressure’ (2017) XXII Art Antiquity and Law pp. 130-142. Bandle, Anne Laure, and Theurich, Sarah. “Alternative Dispute Resolution and Art-Law – A New Research Project of the Geneva Art-Law Centre.” Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2011): 28 – 41 http://www.jiclt.com/index.php/jiclt/article/view/124/122 E. Campfens “Whose cultural heritage? Crimean treasures at the crossroads of politics, law and ethics”, AAL, Vol. XXII, issue 3, (Oct. 2017) http://www.iuscommune.eu/html/activities/2017/2017-11-23/workshop_3_Campfens.pdf Anne Laure Bandle, Raphael Contel, Marc-André Renold, “Case Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva. -

Kurdistan Iraq

Oil magazine no. 27/2014 - Targeted mailshot T 4 N . 0 o 0 u E U w R m O h S b v b e o r e e a a 27 r r r N l r O d V E M B e E R 2014 l magazine e n EDITORIAL i z a g a m Eni quarterly Year 7 - N. 27 November 2014 Authorization from the Court of Rome After the sheikhs: The coming No. 19/2008 dated 01/21/2008 The world over a barrel n Editor in chief Gianni Di Giovanni n Editorial committee collapse of the Gulf monarchies Paul Betts, Fatih Birol, Bassam Fattouh, Guido Gentili, Gary Hart, Harold W. Kroto, he entire Middle East region and East situation extremely well, puts Alessandro Lanza, Lifan Li, e nyone who has anything to cially the United States, the United Kingdom and the n i z a g a Molly Moore, Edward Morse, m also North Africa appear to be forward the theory - difficult to NOVEMBER 2014 Moisés Naím, Daniel Nocera, do with oil must read European Union; the armed forces; the secret police; The Carlo Rossella, Giulio Sapelli world in the midst of a serious crisis. implement but not Utopian - of an Christopher M. Davidson’s and the backing of many citizens, a rich “nomen- over T n a Scientific committee barrel The epicenter, this time, is Syria and international conference, a sort 2013 book After The Sheikhs: clatura” that enjoys the economic privileges that oil Geminello Alvi, Antonio Galdo, Raffaella Leone, Marco Ravaglioli, Iraq, where a civil war is raging and of new Congress of Vienna. -

O Official~ Familiar with the Sessions

- Yaboo! News - Top Ofiicials Queriedo in Israel Ptobe .http://story.news.yahoo.com!news?ttilpJo Yahool My Yahool Mail '~Mbl _ News Home .. Help l!HOOtNews'fIImNew User? Sign UP. ALL INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN I~ UNCLASSIFIED DATE 07-29-2010 BY 60324 uc baw/sab/lsg Personalize News Home Page Vallool News Mon,Aug 30, 2004 Search All News News Home White House· AP Cabinet & State Top Stories Q~eri~d •u.s. NatiOnal Top Officials in ApA880CIated Israel probe .Press Business World Mon Entertainment ~~~2:08 Add White House - AP Ca~inet p& State to My Yahopi SPO~B e Technology PMET Politics By CURT ANDERSON, Associate"d Press Writer Science Health WASHINGTON - High-ranking officials at the (~ Oddly Enough Pentagon .. web sites) and State Department have been inteiviE),wed or briefed by Op/Ed Fal (~ews .. web sites) agents investiQating a Local Def~nse Department arialy~t suspected of Comics passing to Isra~lclassitie~ Bush administratiQn News Photos mate~ials on Iran. , . lYIost Popular Weather . Among those briefed by the FBI IAudloNldeo !;! ; was Douglas J. Feith, the Pentagon Full Coverage uenderse-cretary for pblicy·who is a superior of the analyst under --.......... investigation, said governm~nt AP Photo official~ familiar with the sessions. .J. J ..of4 8/ " Yahoo! News .. Top OtIJcials Querjed'in ~srael ~robe~ ,~~:lIstory.news~Yahoo.com/news.?tnip)" o 0' .. FuU .Coverage, Th~ offiQi~J$ !?pok~ Monday on More about conditio"n pf anonyr:nity Qeca~se t~e prob~ is Espionage & ongoing.' " Intelligence The Fa, ~gents briefed Feith Qn ~\Jnday in his Related News Stories office at tl1Q pentagon· and als~ as~eq . -

The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity Spring 2013 The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India Hannah Donovan Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Political Theory Commons Donovan, Hannah, "The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India" (2013). Annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity. 21. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/student_scholarship/21 It is permitted to copy, distribute, display, and perform this work under the following conditions: (1) the original author(s) must be given proper attribution; (2) this work may not be used for commercial purposes; (3) users must make these conditions clearly known for any reuse or distribution of this work. The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India Hannah Donovan Dr. McCarthy PSC 205 001 December 6, 2012 1 What challenges are posed to formally secular states when religious parties grow in power? Studies of late twentieth century/early twenty-first century Turkey and India begin to answer that question. A major tenet on which both countries were founded was secularism, and their constitutions explicitly state that religion and politics should be separate. Still, millions (and billions, in India’s case) of religious adherents call these two countries home. Moreover, both countries have seen the rise of religious political parties in recent years. This poses a problem, as religious and economic minorities have seen their freedoms decrease. For example, anti-religious rhetoric in Turkey is reprimanded, and openly practicing Muslims in India have seen their houses of worship and fellow Muslims attacked. -

Spying on Friends?: the Franklin Case, AIPAC, and Israel

International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 19: 600–621, 2006 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0885-0607 print=1521-0561 online DOI: 10.1080/08850600600829809 STE´ PHANE LEFEBVRE Spying on Friends?: The Franklin Case, AIPAC, and Israel On 4 August 2005, U.S. Department of Defense official Lawrence Franklin and former American–Israeli Political Action Committee (AIPAC) staffers Steve Rosen and Keith Weissman were indicted on one or several of the following counts: conspiracy to communicate national defense information to persons not entitled to receive it; communication of national defense information to persons not entitled to receive it; and conspiracy to communicate classified information to agents of a foreign government, publicly identified as Israel. Franklin pleaded guilty and cooperated with the authorities, and was subsequently sentenced to a 12-year prison term. As of this writing, Rosen’s and Weissman’s trial was scheduled to start in August 2006. When the story of an investigation into Franklin’s communication of classified information to Rosen and Weissman surfaced, the immediate widely held assumption was that Israel was the ultimate beneficiary. This belief was reinforced with the disclosure that the compromised classified information was related to issues of immediate interest to the Jewish state, including Iran’s nuclear ambitions and the situation in Iraq. But doubts were expressed, to the effect that the cozy relationship between Israel and the United States would hardly necessitate such an intelligence-gathering operation on U.S. soil. Nevertheless, the question of Israel’s precise role in the affair remains unanswered, but for the exception that Franklin told the U.S. -

Navigating the Constraints of the Ummah: a Comparison of Christ Movements in Iran and Bangladesh by Christian J

Peripheral Vision Navigating the Constraints of the Ummah: A Comparison of Christ Movements in Iran and Bangladesh by Christian J. Anderson iscipleship to Jesus always takes place within the contours of particular social contexts, whether it fits smoothly into these social constraints, or rubs abrasively against them. For those following Je- Dsus in the Muslim-majority world, religion is an essential and unavoidable part of this social context. Islam is rarely a privatized or compartmentalized set of beliefs—the practices of its “Five Pillars” are public. Muslim religion interpen- etrates community life, not only intertwining with culture, but integrating with social and political structures. Yet missiologists have often overlooked this key socio-political dimension of Muslim context. Structures (Not Just Culture) as Discipleship Context In the long history and eventual decline of the historic Christian churches in the Muslim world across Asia, the limitations imposed by Muslim socio-political structures were fundamental to the working out of a public, witnessing presence.1 Those constraints continue to be basic to the dynamics of how Christians living under Muslim governments in Asia and Africa congregate and witness. Yet with regard to Muslim-background Christ fellowships and discipleship movements within Islam, western missiology has preferred to focus on religion in terms of cultural contextualization, often neglecting Islam’s social structures as an essential part of that discipleship context. It was anthropologist Charles Kraft’s application of dynamic equivalence theory to the cultural forms that the church might take in a mission context that helped set the direction for the Insider Movement debates.2 The concept of the “homogenous unit principle,” developed by Donald McGavran Christian J. -

Rescue Or Return: the Fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive Bruce P

International Journal of Cultural Property (2013) 20:175–200. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2013 International Cultural Property Society doi:10.1017/S0940739113000040 Rescue or Return: The Fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive Bruce P. Montgomery* Abstract: Shortly following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, an American mobile exploitation team was diverted from its mission in hunting for weapons for mass destruction to search for an ancient Talmud in the basement of Saddam Hussein’s secret police (Mukhabarat) headquarters in Baghdad. Instead of finding the ancient holy book, the soldiers rescued from the basement flooded with several feet of fetid water an invaluable archive of disparate individual and communal documents and books relating to one of the most ancient Jewish communities in the world. The seizure of Jewish cultural materials by the Mukhabarat recalled similar looting by the Nazis during World War II. The materials were spirited out of Iraq to the United States with a vague assurance of their return after being restored. Several years after their arrival in the United States for conservation, the Iraqi Jewish archive has become contested cultural property between Jewish groups and the Iraqi Jewish diaspora on the one hand and Iraqi cultural officials on the other. This article argues that the archive comprises the cultural property and heritage of the Iraqi Jewish diaspora. I. INTRODUCTION In early May 2003, a U.S. mobile exploitation team (MET) was diverted from its mission in hunting for weapons of mass destruction to rescue an ancient Tal- mud, a Jewish holy book, in the basement of the Mukhabarat, Saddam Hussein’s secret police headquarters. -

208 Turkeys Crises Over Israel and Iran

TURKEY’S CRISES OVER ISRAEL AND IRAN Europe Report N°208 – 8 September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TURKEY AND ISRAEL: LOST AT SEA ...................................................................... 2 A. ISRAEL AND THE AKP .................................................................................................................. 2 B. THE MAVI MARMARA AFFAIR ........................................................................................................ 4 1. The IHH ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2. A tragedy of errors ....................................................................................................................... 5 C. A BITTER AFTERMATH ................................................................................................................ 8 III. TURKEY AND IRAN: AGE-OLD SPARRING PARTNERS .................................... 10 A. NO ALLIANCE ............................................................................................................................ 10 B. IRAN’S NUCLEAR PROGRAM AND TURKEY ................................................................................. 11 IV. CALMING THE DEBATE ........................................................................................... -

The Emergence of Iran's Revolutionary Guards' Regime

Iran: From Regional Challenge to Global Threat A Jerusalem Center Anthology Brig.-Gen. (ret.) Dr. Shimon Shapira (ed.) with Amb. Dore Gold, Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Yaakov Amidror, Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Aharon Ze'evi Farkash, Brig.-Gen (ret.) Yossi Kuperwasser, Dr. Shmuel Bar, Uzi Rubin, Lt.-Col. (ret.) Michael Segall, Dr. Harold Rhode, Col. (ret.) Dr. Jacques Neriah, Amb. Zvi Mazel Published by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Other ebook titles by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: Israel's Critical Security Requirements for Defensible Borders Israel's Rights as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] – www.jcpa.org ISBN: 978-1-4657-5950-4 Production Director: Mark Ami-El Cover: Iran Nuclear Facility at Fordow * * * * * Contents Foreword – Shimon Shapira Part I – The Military Threat from Iran The Threat from Nuclear Weapons What Is Happening to the Iranian Nuclear Program? Dore Gold The U.S. National Intelligence Estimate on Iran and Its Aftermath: A Roundtable of Israeli Experts Yaakov Amidror, Aharon Ze'evi Farkash, and Yossi Kuperwasser The Limited Influence of International Sanctions on Iran's Nuclear Program Yossi Kuperwasser Iran Signals Its Readiness for a Final Confrontation Michael Segall Can Cold War Deterrence Apply to a Nuclear Iran? Shmuel Bar Other Iranian Military Capabilities New Developments in Iran's Missile Capabilities: