Rescue Or Return: the Fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive Bruce P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sources of Iranian Negotiating Behavior

STR The Sources of Iranian Negotiating Behavior Harold Rhode TEGIC STRAPERSPECTIVES E XECUTIVE SUMMARY This analysis identifies patterns exhibited by the Iranian government and the Iranian people since ancient times. Most importantly, it identifies critical elements of Iranian culture that have been systematically ignored by policymakers for decades. It is a precise understanding of these cultural cues that should guide policy objectives toward the Iranian government. Iranians expect a ruler to demonstrate resolve and strength, and do whatever it takes to remain in power. The Western concept of demanding that a leader subscribe to a moral and ethical code does not resonate with Iranians. Telling Iranians that their ruler is cruel will not convince the public that they need a new leader. To the contrary, this will reinforce the idea that their ruler is strong. It is only when Iranians become convinced that either their rulers lack the resolve to do what is necessary to remain in power or that a stronger power will protect them against their current tyrannical rulers, that they will speak out and try to overthrow leaders. Compromise (as we in the West understand this concept) is seen as a sign of submission and weakness. For Iranians, it actually brings shame on those (and on the families of those) who concede. By contrast, one who forces others to compromise increases his honor and stature, and is likely to continue forcing others to submit in the future. Iranians do not consider weakness a reason to engage an adversary in compromise, but rather as an opportunity to destroy them. -

Turkey by HAROLD RHODE Chapter 2

Ally No More Ally No More Erdoğan’s New Turkish Caliphate and the Rising Jihadist Threat to the West Center for Security Policy Press This book may be reproduced, distributed and transmitted for personal and non-commercial use. Contact the Center for Security Policy for bulk order information. For more information about this book, visit SECUREFREEDOM.ORG Ally No More: Erdoğan’s New Turkish Caliphate and the Rising Jihadist Threat to the West is published in the United States by the Center for Security Policy Press, a division of the Center for Security Policy. ISBN-13: ISBN978-1717071675-10: 1717071678 The Center for Security Policy Washington, D.C. Phone: 202-835-9077 Email: [email protected] For more information, visit SecureFreedom.org Book design by Bravura Books Contents Foreword ................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 5 How to Understand Erdoğan & His Neo-Ottoman Strategy to Destroy Ataturk’s Turkey BY HAROLD RHODE Chapter 2 .................................................................................................. 23 Turkey’s Partnership with the U.S. Muslim Brotherhood BY CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY STAFF Chapter 3 .................................................................................................. 51 Gülen and Erdoğan: Partners on a Brotherhood Mission BY CLARE M. LOPEZ Chapter 4 ................................................................................................. -

A Wave of Progressives Shows Israel Criticism Isn't Taboo Anymore

Jewish Federation of NEPA Non-profit Organization 601 Jefferson Ave. U.S. POSTAGE PAID The Scranton, PA 18510 Permit # 184 Watertown, NY Change Service Requested Published by the Jewish Federation of Northeastern Pennsylvania VOLUME XI, NUMBER 14 JULY 26, 2018 A wave of progressives shows Israel criticism isn’t taboo anymore an “intersectional feminist” table criticism, the general trends it notes ANALYSIS and Israel an apartheid have been shown elsewhere. regime. In Virginia’s 5th Some credit Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) BY CHARLES DUNST Congressional District, with normalizing such criticism of Israel. NEW YORK (JTA) – After Alexan- Democratic nominee Leslie While the 2016 Democratic presidential dria Ocasio-Cortez shocked the political Cockburn is the co-author, candidate defined himself as “100 percent world by defeating longtime New York along with her husband, of pro-Israel,” he recently called on the U.S. Rep. Joseph Crowley in a Democratic “Dangerous Liaison: The to adopt a more balanced policy toward primary in June, Democratic National Inside Story of the U.S.-Is- Israel and the Palestinians. In late March, Committee Chairman Tom Perez quickly raeli Covert Relationship,” Sanders’ office posted three videos to Ilhan Omar at the premiere aligned himself with the former political a scathing 1991 attack on social media criticizing Israel for what outsider, saying on a radio show that “she the Jewish state. of “Time For Ilhan,” a film he deemed its excessive use of force in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez about her congressional represents the future of our party.” “It seems to me that some appeared on “Meet the Gaza and the Trump administration for If so, that future appears to include criticism of Israel is part of a seat run, during the 2018 not intervening during the border clashes. -

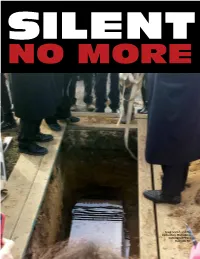

Silent No More

SILENT NO MORE Iraqi jewish archive burial New Montefiore Cemetery in West Babylon, NY IRAQI JEWS SILENT FIGHT FOR THE OWNERSHIP OF THEIR HERITAGE BY MACHLA ABRAMOVITZ he scene at New Montefiore Cemetery in West Babylon, the fragments was negotiated by Maurice Shohet, president of the New York on the wet and chilly afternoon of December World Organization of Iraqi Jews (WOJI). 15 was nothing less than surrealistic. Mingling sociably These, together with thousands of priceless Jewish artifacts res- with over 100 Iraqi Jews who had come from far and cued in 2003 from the flooded basement of Saddam Hussein’s Twide was Lukman Faily, Iraq’s new ambassador to the United intelligence headquarters, had been brought out of Iraq only after States, as well as dignitaries from the Iraqi Ministries of the Inte- an agreement between NARA and Iraq’s interim government was rior, Foreign Affairs and National Security Council who had flown signed, legally binding the US to return the materials to Iraq by in from Baghdad for the occasion. Also attending was US State June 2014. Department Director of Near East and African Affairs Anthony Once in the States, they were lovingly and meticulously Godfrey and Doris Hamburg, Director of the National Archives cleaned, repaired, conserved and digitized by NARA under the and Records Administration preservation program (NARA). They care of Hamburg and Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler, chief of the Docu- had come to bury close to 50 fragments of damaged Torah scrolls ment Conservation Laboratory, at a cost to the State Department and Megillos Esther that were beyond repair and had been part of about $3 million. -

The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation 9 Annual

The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation 9th Annual Conference Friday, April 13, 2018 8:00am-6:30pm Georgetown University Law Center McDonough Hall, Hart Auditorium 600 New Jersey Ave NW, Washington, DC 20001 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Panel 1: Claiming and Disclaiming Ownership: Russian, Ukrainian, both or neither? Panel 2: Whose Property? National Claims versus the Rights of Religious and Ethnic Minorities in the Middle East Panel 3: Protecting Native American Cultural Heritage Panel 4: Best Practices in Acquiring and Collecting Cultural Property Speaker Biographies CLE MATERIALS FOR PANEL 1 Laws/ Regulations Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-confiscated Art (1998) https://www.state.gov/p/eur/rt/hlcst/270431.htm Articles/ Book Chapters/ White Papers Quentin Byrne-Sutton, Arbitration and Mediation in Art-Related Disputes, ARBITRATION INT’L 447 (1998). F. Shyllon, ‘The Rise of Negotiation (ADR) in Restitution, Return and Repatriation of Cultural Property: Moral Pressure and Power Pressure’ (2017) XXII Art Antiquity and Law pp. 130-142. Bandle, Anne Laure, and Theurich, Sarah. “Alternative Dispute Resolution and Art-Law – A New Research Project of the Geneva Art-Law Centre.” Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2011): 28 – 41 http://www.jiclt.com/index.php/jiclt/article/view/124/122 E. Campfens “Whose cultural heritage? Crimean treasures at the crossroads of politics, law and ethics”, AAL, Vol. XXII, issue 3, (Oct. 2017) http://www.iuscommune.eu/html/activities/2017/2017-11-23/workshop_3_Campfens.pdf Anne Laure Bandle, Raphael Contel, Marc-André Renold, “Case Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva. -

Kurdistan Iraq

Oil magazine no. 27/2014 - Targeted mailshot T 4 N . 0 o 0 u E U w R m O h S b v b e o r e e a a 27 r r r N l r O d V E M B e E R 2014 l magazine e n EDITORIAL i z a g a m Eni quarterly Year 7 - N. 27 November 2014 Authorization from the Court of Rome After the sheikhs: The coming No. 19/2008 dated 01/21/2008 The world over a barrel n Editor in chief Gianni Di Giovanni n Editorial committee collapse of the Gulf monarchies Paul Betts, Fatih Birol, Bassam Fattouh, Guido Gentili, Gary Hart, Harold W. Kroto, he entire Middle East region and East situation extremely well, puts Alessandro Lanza, Lifan Li, e nyone who has anything to cially the United States, the United Kingdom and the n i z a g a Molly Moore, Edward Morse, m also North Africa appear to be forward the theory - difficult to NOVEMBER 2014 Moisés Naím, Daniel Nocera, do with oil must read European Union; the armed forces; the secret police; The Carlo Rossella, Giulio Sapelli world in the midst of a serious crisis. implement but not Utopian - of an Christopher M. Davidson’s and the backing of many citizens, a rich “nomen- over T n a Scientific committee barrel The epicenter, this time, is Syria and international conference, a sort 2013 book After The Sheikhs: clatura” that enjoys the economic privileges that oil Geminello Alvi, Antonio Galdo, Raffaella Leone, Marco Ravaglioli, Iraq, where a civil war is raging and of new Congress of Vienna. -

1 Is the United States Returning Stolen Cultural

Is the United States Returning Stolen Cultural Property to the Countries that Committed the Theft in the First Place? Treatment of the Iraqi Jewish Archive and Other Property Under U.S. Statutes and Memoranda of Understanding with Algeria, Syria, Egypt and Libya and proposed with Yemen By: Carole Basri as of October 15, 2019 (based on my article written in the American Bar Association Section of International Law, Fall 2018, Art & Cultural Heritage Law Newsletter) In May 2003, over 2700 Jewish books and tens of thousands of documents, records, and religious artifacts were discovered by a U.S. Army team in the flooded basement of the Iraqi intelligence headquarters. The written records provide a better understanding of the 2700 year- old Iraqi Jewish community. The Jewish Iraqi Archive was brought to the U.S. to be preserved, cataloged, and digitized, and has been exhibited in various cities for several years. Based on an agreement signed on August 19, 2003 between the Coalition Provisional Authority and the National Archives and Records Administration,1 and extended by the U.S. Government in an Executive Order by President Obama, the Iraqi Jewish Archive was to have been returned to Iraq after September 2018. Then on a parallel track, but unbeknownst to the Iraqi Jewish community, Congress amended the Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act of 2004 in 2008 to include import restrictions on Jewish artifacts. These import restrictions included Torahs and other Jewish artifacts made on or before 1990.2 After this, the U.S. State Department put together separate Memoranda of Understanding regarding Jewish religious and cultural artifacts from Algeria, Syria, Egypt and Libya. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Iraq & Iran Issue Iran and Iraq: Demography beyond the Jewish Past 6 Sergio DellaPergola AJS, Ahmadinejad, and Me 8 Richard Kalmin Baghdad in the West: Migration and the Making of Medieval Jewish Traditions 11 Marina Rustow Jews of Iran and Rabbinical Literature: Preliminary Notes 14 Daniel Tsadik Iraqi Arab-Jewish Identities: First Body Singular 18 Orit Bashkin A Republic of Letters without a Republic? 24 Lital Levy A Fruit That Asks Questions: Michael Rakowitz’s Shipment of Iraqi Dates 28 Jenny Gheith On Becoming Persian: Illuminating the Iranian-Jewish Community 30 Photographs by Shelley Gazin, with commentary by Nasrin Rahimieh JAPS: Jewish American Persian Women and Their Hybrid Identity in America 34 Saba Tova Soomekh Engagement, Diplomacy, and Iran’s Nuclear Program 42 Brandon Friedman Online Resources for Talmud Research, Study, and Teaching 46 Heidi Lerner The Latest Limmud UK 2009 52 Caryn Aviv A Serious Man 53 Jason Kalman The Questionnaire What development in Jewish studies over the last twenty years has most excited you? 55 AJS Perspectives: The Magazine of the President Please direct correspondence to: Association for Jewish Studies Marsha Rozenblit Association for Jewish Studies University of Maryland Center for Jewish History Editors 15 West 16th Street Matti Bunzl Vice President/Publications New York, NY 10011 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Jeffrey Shandler Rachel Havrelock Rutgers University Voice: (917) 606-8249 University of Illinois at Chicago Fax: (917) 606-8222 Vice President/Program E-Mail: [email protected] Derek Penslar Web Site: www.ajsnet.org Editorial Board Allan Arkush University of Toronto Binghamton University AJS Perspectives is published bi-annually Vice President/Membership by the Association for Jewish Studies. -

O Official~ Familiar with the Sessions

- Yaboo! News - Top Ofiicials Queriedo in Israel Ptobe .http://story.news.yahoo.com!news?ttilpJo Yahool My Yahool Mail '~Mbl _ News Home .. Help l!HOOtNews'fIImNew User? Sign UP. ALL INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN I~ UNCLASSIFIED DATE 07-29-2010 BY 60324 uc baw/sab/lsg Personalize News Home Page Vallool News Mon,Aug 30, 2004 Search All News News Home White House· AP Cabinet & State Top Stories Q~eri~d •u.s. NatiOnal Top Officials in ApA880CIated Israel probe .Press Business World Mon Entertainment ~~~2:08 Add White House - AP Ca~inet p& State to My Yahopi SPO~B e Technology PMET Politics By CURT ANDERSON, Associate"d Press Writer Science Health WASHINGTON - High-ranking officials at the (~ Oddly Enough Pentagon .. web sites) and State Department have been inteiviE),wed or briefed by Op/Ed Fal (~ews .. web sites) agents investiQating a Local Def~nse Department arialy~t suspected of Comics passing to Isra~lclassitie~ Bush administratiQn News Photos mate~ials on Iran. , . lYIost Popular Weather . Among those briefed by the FBI IAudloNldeo !;! ; was Douglas J. Feith, the Pentagon Full Coverage uenderse-cretary for pblicy·who is a superior of the analyst under --.......... investigation, said governm~nt AP Photo official~ familiar with the sessions. .J. J ..of4 8/ " Yahoo! News .. Top OtIJcials Querjed'in ~srael ~robe~ ,~~:lIstory.news~Yahoo.com/news.?tnip)" o 0' .. FuU .Coverage, Th~ offiQi~J$ !?pok~ Monday on More about conditio"n pf anonyr:nity Qeca~se t~e prob~ is Espionage & ongoing.' " Intelligence The Fa, ~gents briefed Feith Qn ~\Jnday in his Related News Stories office at tl1Q pentagon· and als~ as~eq . -

The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity Spring 2013 The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India Hannah Donovan Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Political Theory Commons Donovan, Hannah, "The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India" (2013). Annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity. 21. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/student_scholarship/21 It is permitted to copy, distribute, display, and perform this work under the following conditions: (1) the original author(s) must be given proper attribution; (2) this work may not be used for commercial purposes; (3) users must make these conditions clearly known for any reuse or distribution of this work. The Rise of Religious Parties in Turkey and India Hannah Donovan Dr. McCarthy PSC 205 001 December 6, 2012 1 What challenges are posed to formally secular states when religious parties grow in power? Studies of late twentieth century/early twenty-first century Turkey and India begin to answer that question. A major tenet on which both countries were founded was secularism, and their constitutions explicitly state that religion and politics should be separate. Still, millions (and billions, in India’s case) of religious adherents call these two countries home. Moreover, both countries have seen the rise of religious political parties in recent years. This poses a problem, as religious and economic minorities have seen their freedoms decrease. For example, anti-religious rhetoric in Turkey is reprimanded, and openly practicing Muslims in India have seen their houses of worship and fellow Muslims attacked. -

Spying on Friends?: the Franklin Case, AIPAC, and Israel

International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 19: 600–621, 2006 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0885-0607 print=1521-0561 online DOI: 10.1080/08850600600829809 STE´ PHANE LEFEBVRE Spying on Friends?: The Franklin Case, AIPAC, and Israel On 4 August 2005, U.S. Department of Defense official Lawrence Franklin and former American–Israeli Political Action Committee (AIPAC) staffers Steve Rosen and Keith Weissman were indicted on one or several of the following counts: conspiracy to communicate national defense information to persons not entitled to receive it; communication of national defense information to persons not entitled to receive it; and conspiracy to communicate classified information to agents of a foreign government, publicly identified as Israel. Franklin pleaded guilty and cooperated with the authorities, and was subsequently sentenced to a 12-year prison term. As of this writing, Rosen’s and Weissman’s trial was scheduled to start in August 2006. When the story of an investigation into Franklin’s communication of classified information to Rosen and Weissman surfaced, the immediate widely held assumption was that Israel was the ultimate beneficiary. This belief was reinforced with the disclosure that the compromised classified information was related to issues of immediate interest to the Jewish state, including Iran’s nuclear ambitions and the situation in Iraq. But doubts were expressed, to the effect that the cozy relationship between Israel and the United States would hardly necessitate such an intelligence-gathering operation on U.S. soil. Nevertheless, the question of Israel’s precise role in the affair remains unanswered, but for the exception that Franklin told the U.S. -

Navigating the Constraints of the Ummah: a Comparison of Christ Movements in Iran and Bangladesh by Christian J

Peripheral Vision Navigating the Constraints of the Ummah: A Comparison of Christ Movements in Iran and Bangladesh by Christian J. Anderson iscipleship to Jesus always takes place within the contours of particular social contexts, whether it fits smoothly into these social constraints, or rubs abrasively against them. For those following Je- Dsus in the Muslim-majority world, religion is an essential and unavoidable part of this social context. Islam is rarely a privatized or compartmentalized set of beliefs—the practices of its “Five Pillars” are public. Muslim religion interpen- etrates community life, not only intertwining with culture, but integrating with social and political structures. Yet missiologists have often overlooked this key socio-political dimension of Muslim context. Structures (Not Just Culture) as Discipleship Context In the long history and eventual decline of the historic Christian churches in the Muslim world across Asia, the limitations imposed by Muslim socio-political structures were fundamental to the working out of a public, witnessing presence.1 Those constraints continue to be basic to the dynamics of how Christians living under Muslim governments in Asia and Africa congregate and witness. Yet with regard to Muslim-background Christ fellowships and discipleship movements within Islam, western missiology has preferred to focus on religion in terms of cultural contextualization, often neglecting Islam’s social structures as an essential part of that discipleship context. It was anthropologist Charles Kraft’s application of dynamic equivalence theory to the cultural forms that the church might take in a mission context that helped set the direction for the Insider Movement debates.2 The concept of the “homogenous unit principle,” developed by Donald McGavran Christian J.