July 2017 Sigar-17-53-Sp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CB Meeting PAK/AFG

Polio Eradication Initiative Afghanistan Current Situation of Polio Eradication in Afghanistan Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 29-30 April 2015,Abu Dhabi AFP cases Classification, Afghanistan Year 2013 2014 2015 Reported AFP 1897 2,421 867 cases Confirmed 14 28 1 Compatible 4 6 0 VDPV2 3 0 0 Discarded 1876 2,387 717 Pending 0 0 *149 Total of 2,421 AFP cases reported in 2014 and 28 among them were confirmed Polio while 6 labelled* 123as Adequatecompatible AFP cases Poliopending lab results 26 Inadequate AFP cases pending ERC 21There Apr 2015 is one Polio case reported in 2015 as of 21 April 2015. Region wise Wild Poliovirus Cases 2013-2014-2015, Afghanistan Confirmed cases Region 2013 2014 2015 Central 1 0 0 East 12 6 0 2013 South east 0 4 0 Districts= 10 WPV=14 South 1 17 1 North 0 0 0 Northeast 0 0 0 West 0 1 0 Polio cases increased by 100% in 2014 Country 14 28 1 compared to 2013. Infected districts increased 2014 District= 19 from 10 to 19 in 2014. WPV=28 28 There30 is a case surge in Southern Region while the 25Eastern Region halved the number of cases20 in comparison14 to 2013 Most15 of the infected districts were in South, East10 and South East region in 2014. No of AFP cases AFP of No 1 2015 5 Helmand province reported a case in 2015 District= 01 WPV=01 after0 a period of almost two months indicates 13 14 15 Year 21continuation Apr 2015 of low level circulation. Non Infected Districts Infected Districts Characteristics of polio cases 2014, Afghanistan • All the cases are of WPV1 type, 17/28 (60%) cases are reported from Southern region( Kandahar-13, Helmand-02, and 1 each from Uruzgan and Zabul Province). -

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (12 – 18 July 2021)

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (12 – 18 July 2021) KEY FIGURES IDPs IN 2021 (AS OF 18 JULY) 294,703 People displaced by conflict (verified) 152,387 Received assistance (including 2020 caseload) NATURAL DISASTERS IN 2021 (AS OF 11 JULY) 24,073 Number of people affected by natural disasters Conflict incident RETURNEES IN 2021 Internal displacement (AS OF 18 JULY) 621,856 Disruption of services Returnees from Iran 7,251 Returnees from Pakistan 45 South: Fighting continues including near border Returnees from other Kandahar and Hilmand province witnessed a significant spike in conflict during countries the reporting period. A Non-State Armed Group (NSAG) reportedly continued to HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE apply pressure on District Administrative Centres (DACs) and provincial capitals PLAN (HRP) REQUIREMENTS & to expand areas under their control while Afghan National Security Forces FUNDING (ANSF) conducted clearing operations supported by airstrikes. Ongoing conflict reportedly led to the displacement of civilians with increased fighting resulting in 1.28B civilian casualties in Dand and Zheray districts in Kandahar province and Requirements (US$) – HRP Lashkargah city in Hilmand province. 2021 The intermittent closure of roads to/from districts and provinces, particularly in 479.3M Hilmand and Kandahar provinces, hindered civilian movements and 37% funded (US$) in 2021 transportation of food items and humanitarian/medical supplies. Intermittent AFGHANISTAN HUMANITARIAN outages of mobile service continued. On 14 July, an NSAG reportedly took FUND (AHF) 2021 control of posts and bases around the Spin Boldak DAC and Wesh crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Closure of the border could affect trade and 43.61M have adverse implications on local communities and the region. -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

Afghanistan: Annual Report 2014

AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT © 2014/Ihsanullah Mahjoor/Associated Press United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan February 2015 Kabul, Afghanistan July 2014 Source: UNAMA GIS January 2012 AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan February 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2014/Ihsanullah Mahjoor/Associated Press. Bodies of civilians killed in a suicide attack on 23 November 2014 in Yahyakhail district, Paktika province that caused 138 civilian casualties (53 killed including 21 children and 85 injured including 26 children). Photo taken on 24 November 2014. "The conflict took an extreme toll on civilians in 2014. Mortars, IEDs, gunfire and other explosives destroyed human life, stole limbs and ruined lives at unprecedented levels. The thousands of Afghan children, women and men killed and injured in 2014 attest to failures to protect civilians from harm. All parties must uphold the values they claim to defend and make protecting civilians their first priority.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan, December 2014, Kabul “This annual report shows once again the unacceptable price that the conflict is exacting on the civilian population in Afghanistan. Documenting these trends should not be regarded -

Afghanistan's Insurgency After the Transition

Afghanistan’s Insurgency after the Transition Asia Report N°256 | 12 May 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Transitioning to December 2014 ...................................................................................... 3 A. Escalating Violence .................................................................................................... 3 B. Fears of Greater Instability in 2014-2015 .................................................................. 4 C. Stalled Peace Talks ..................................................................................................... 4 D. Pakistan’s Role ........................................................................................................... 5 E. Insurgent Factions Gain Prominence ........................................................................ 6 F. Motivation to Fight .................................................................................................... 7 G. Assessing the Insurgency .......................................................................................... -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

ICC-02/17 Date: 20 November 2017 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before

ICC-02/17-7-Red 20-11-2017 1/181 NM PT ras Original: English No.: ICC-02/17 Date: 20 November 2017 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Antoine Kesia-Mbe Mindua, Presiding Judge Judge Chang-ho Chung Judge Raul C. Pangalangan SITUATION IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN PUBLIC with confidential, EX PARTE, Annexes 1, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 4A, 4B, 4C, 6, public Annexes 4, 5 and 7, and public redacted version of Annex 1-Conf-Exp Public redacted version of “Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15”, 20 November 2017, ICC-02/17-7-Conf-Exp Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-02/17-7-Red 20-11-2017 2/181 NM PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Mrs Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Mr Benjamin Gumpert Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Defence Support Section Mr Herman von Hebel Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Mr Nigel Verrill No. ICC- 02/17 2/181 20 November 2017 ICC-02/17-7-Red 20-11-2017 3/181 NM PT I. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 6 II. Confidentiality ................................................................................................. -

Kunar Province

AFGHANISTAN Kunar Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Kunar Province Reference Map 71°0'0"E 71°30'0"E Barg-e-Matal District Koran Badakhshan Wa Monjan District Province Kamdesh 35°30'0"N District 35°30'0"N Poruns Kamdesh !! Poruns ! District Nuristan Province Chitral Nari District Ghaziabad Nari District ! Waygal District Waygal Wama ! District Nurgeram District Ghaziabad ! Wama ! Upper Dir Barkunar Khyber Shigal District Pakhtunkhwa Wa Sheltan Barkunar District ! Watapur Dangam District ! 35°0'0"N Chapadara Dara-e-Pech Shigal Wa 35°0'0"N ! ! Sheltan Dangam Chapadara ! District Dara-e-Pech District District Watapur Lower ! Dir Marawara ! Asadabad !! Asadabad ! Alingar District Marawara District District Kunar Bajaur Province Agency Sarkani Narang ! District Narang ! Sarkani Chawkay District District PAKISTAN Dara-e-Nur Chawkay District Nurgal ! District Dara-e-Nur Khaskunar ! ! Fata Nurgal ! Khaskunar District Kuzkunar ! Kuzkunar District Mohmand Agency Nangarhar 34°30'0"N 34°30'0"N Province Goshta District Kama District Lalpur Kama ! District 71°0'0"E 71°30'0"E Legend Date Printed: 27 March 2014 01:34 PM UZBEKISTAN CHINA Data -

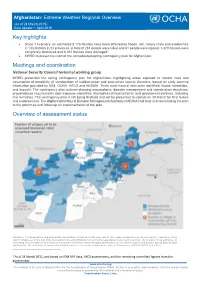

Key Highlights Meetings and Coordination Overview of Assessment Status

Afghanistan: Extreme Weather Regional Overview (as of 24 March 2015) Next update: 1 April 2015 Key highlights Since 1 February, an estimated 8,176 families have been affected by floods, rain, heavy snow and avalanches in 133 districts in 24 provinces. A total of 281 people were killed and 81 people were injured. 1,429 houses were completely destroyed and 6,357 houses were damaged1. MRRD to present to cabinet the consolidated spring contingency plan for Afghanistan. Meetings and coordination National Security Council technical working group MRRD presented the spring contingency plan for Afghanistan, highlighting areas exposed to hazard risks and assumption of possibility of combination of sudden-onset and slow-onset natural disasters, based on early warning information provided by IOM, OCHA, ARCS and ANDMA. Three main hazard risks were identified: floods; landslides, and drought. The contingency plan outlines planning assumptions, disaster management and coordination structures, preparedness requirements and response capacities (stockpiles) of humanitarian and government partners, including line ministries. The contingency plan is still being finalized and will be presented to cabinet on 30 March for final review and endorsement. The Afghanistan Natural Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA) will lead in disseminating the plan to the provinces and follow up on implementation of the plan. Overview of assessment status Number of villages yet to be assessed (based on initial unverified reports) Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map, and all other maps contained herein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Operation HAMMER DOWN in an Area Immediately to the East of the Waygal River Valley

HAMMER DOWN The Battle for the Watapur Valley, 2011 Ryan D. Wadle, Ph. D. Combat Studies Institute Press US Army Combined Arms Center Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Photos in this publication provided by Major Christopher Bluhm, US Army, in February of 2014. Photo permission for use in this study is provided by Battalion Commander Lieutenant Colonel Tuley and Battalion Sergeant Major Jones. Graphics are author and CSI generated. CGSC Copyright Registration #14-0480 C/E, 0481 C/E, 14- 0482 C/E, 14-0483 HAMMER DOWN The Battle for the Watapur Valley, 2011 Ryan D. Wadle, Ph. D. Volume III of the Vanguard of Valor series Combat Studies Institute Press US Army Combined Arms Center Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data HAMMER DOWN: The Battle for the Watapur Valley, 2011 Vanguard of Valor III p. cm. 1. Afghan War, 2001---Campaigns. 2. Counterinsurgency--Afghanistan. 3. United States. Army--History--Afghan War, 2001- 4. Afghanistan-- History, Military--21st century. I. Ryan D. Wadle, Ph.D. DS371.412.V362 2012 958.104’742--dc23 2014 CGSC Copyright Registration #14-0480 C/E, 0481 C/E, 14-0482 C/E, 14-0483 Second printing: Fall 2014 Editing and layout by Carl W. Fischer, 2014 Combat Studies Institute Press publications cover a wide variety of military history topics. The views expressed in this CSI Press publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. A full list of CSI Press publications available for downloading can be found at http://usacac.army.mil/CAC2/CSI/index.asp. -

Protection Overview on the Eastern and South-Eastern Regions 30 November 2011, Final Version

Afghanistan Protection Cluster: Protection Overview on the Eastern and South-Eastern Regions 30 November 2011, Final Version AFGHANISTAN PROTECTION CLUSTER Protection Overview Eastern and South-Eastern Regions 2010 / 2011 I. Introduction II. Security Situation III. Human Rights Violations IV. Humanitarian Access V. Afghan Returnees VI. Internal Displacement VII. Conclusion Annexe 1 – Internal Displacement 1 Afghanistan Protection Cluster: Protection Overview on the Eastern and South-Eastern Regions 30 November 2011, Final Version I. Introduction The South Eastern Region (SER) and the Eastern Region (ER) are at the heart of the current military conflict between Pro-Government Forces (PGF) and Anti-Government Elements (AGEs). They have also served as strategic battlefields during the Soviet invasion due to proximity with Pakistan and the rugged terrain they encompass. Paktya, Khost and Paktika (SER) and Nangrahar, Kunar, Nuristan and Laghman (ER) border Pakistan and its volatile agencies of Khyber Pukhtoon Khwa (KPK). The Pakistani South and North Waziristan Khoram Agency, as well as the Khyber Mohmand and Bajaur Agencies that form the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), are reported ridden with insecurity and active insurgency impacting both Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Durand line is not recognized officially by the two States and the border that divides a predominantly Pashtun area is porous1. The ER is also strategic for the International Military Forces (IMF) and the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) as most of their supplies travel through the Pakistan - Afghanistan border crossing at Torkham. Control of the area surrounding the road linking Jalalabad with Kabul, is of immense strategic importance. The same route is used for essential imported economic goods for the country.