An Overview of Active Flow Control Enhanced Vertical Tail Technology Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Environmental Report

Build Something Cleaner The Boeing Company 2016 Environment Report OUR APPROACH DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MANUFACTURING AND OPERATIONS IN SERVICE END OF SERVICE APPENDIX About The Boeing Company Total revenue in For five straight Currently holds 2015: $96.1 billion years, has been 15,600 active named a top global patents around Employs 160,000 innovator among the world people across the aerospace and United States and in defense companies Has customers in more than 65 other 150 countries countries Established 11 research and For more than a 21,500 suppliers development centers, decade, has been and partners 17 consortia and the No.1 exporter around the world 72 joint global in the United States research centers OUR APPROACH DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MANUFACTURING AND OPERATIONS IN SERVICE END OF SERVICE APPENDIX At Boeing, we aspire to be the strongest, best and best-integrated aerospace-based company in the world— and a global industrial champion—for today and tomorrow. CONTENTS Our Approach 2 Design and Development 18 Manufacturing and Operations 28 In Service 38 End of Service 46 Jonathon Jorgenson, left, and Cesar Viray adjust drilling equipment on the 737 MAX robotic cell pulse line at Boeing’s fab- rication plant in Auburn, Washington. Automated production is helping improve the efficiency of aircraft manufacturing. (Boeing photo) 1 OUR APPROACH DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MANUFACTURING AND OPERATIONS IN SERVICE END OF SERVICE APPENDIX As Boeing celebrates Our Approach its first century, we are looking forward to the innovations of the next 100 years. We are working to be the most environmentally progressive aero- space company and an enduring global industrial champion. -

Aviation Week & Space Technology

STARTS AFTER PAGE 34 Using AI To Boost How Emirates Is Extending ATM Efficiency Maintenance Intervals ™ $14.95 JANUARY 13-26, 2020 2020 THE YEAR OF SUSTAINABILITY RICH MEDIA EXCLUSIVE Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

FLYHT 2019 July Investor Presentation

July 2019 FLYHT Aerospace Solutions Ltd. TSX.V: FLY OTCQX: FLYLF 1 TSX.V: FLY OTCQX: FLYLF Disclaimer www.flyht.com Forward Looking Statements This discussion includes certain statements that may be deemed “forward-looking statements” that are subject to risks and uncertainty. All statements, other than statements of historical facts included in this discussion, including, without limitation, those regarding the Company’s financial position, business strategy, projected costs, future plans, projected revenues, objectives of management for future operations, the Company’s ability to meet any repayment obligations, the use of non-GAAP financial measures, trends in the airline industry, the global financial outlook, expanding markets, research and development of next generation products and any government assistance in financing such developments, foreign exchange rate outlooks, new revenue streams and sales projections, cost increases as related to marketing, research and development (including AFIRS 228), administration expenses, and litigation matters, may be or include forward-looking statements. Although the Company believes the expectations expressed in such forward-looking statements are based on a number of reasonable assumptions regarding the Canadian, U.S., and global economic environments, local and foreign government policies/regulations and actions and assumptions made based upon discussions to date with the Company’s customers and advisers, such statements are not guarantees of future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those in the forward- looking statements. Factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those in the forward-looking statements include production rates, timing for product deliveries and installations, Canadian, U.S., and foreign government activities, volatility of the aviation market for the Company’s products and services, factors that result in significant and prolonged disruption of air travel worldwide, U.S. -

Boeing Environment Report 2017

THE BOEING COMPANY 2017 ENVIRONMENT REPORT BUILD SOMETHING CLEANER 1 ABOUT US Boeing begins its second century of business with a firm commitment to lead the aerospace industry into an environmentally progressive and sustainable future. Our centennial in 2016 marked 100 years of Meeting climate change and other challenges innovation in products and services that helped head-on requires a global approach. Boeing transform aviation and the world. The same works closely with government agencies, dedication is bringing ongoing innovation in more customers, stakeholders and research facilities efficient, cleaner products and operations for worldwide to develop solutions that help protect our employees, customers and communities the environment. around the globe. Our commitment to a cleaner, more sustainable Our strategy and actions reflect goals and future drives action at every level of the company. priorities that address the most critical environ- Every day, thousands of Boeing employees lead mental challenges facing our company, activities and projects that advance progress in customers and industry. Innovations that reducing emissions and conserving water and improve efficiency across our product lines resources. and throughout our operations drive reductions This report outlines the progress Boeing made in emissions and mitigate impacts on climate and challenges we encountered in 2016 toward change. our environmental goals and strategy. We’re reducing waste and water use in our In the face of rapidly changing business and facilities, even as we see our business growing. environmental landscapes, Boeing will pursue In addition, we’re finding alternatives to the innovation and leadership that will build a chemicals and hazardous materials in our brighter, more sustainable future for our products and operations, and we’re leading the employees, customers, communities and global development of sustainable aviation fuels. -

The Boeing Company 2014 Annual Report

The Boeing Company 100 North Riverside Plaza Chicago, IL 60606-1596 Leading Ahead USA The Boeing Company 2014 Annual Report The Boeing Company Contents Boeing is the world’s largest aerospace Operational Highlights 1 company and leading manufacturer Message From Our Chairman 2 Engagement of commercial airplanes and defense, The Executive Council 8 space and security systems. The top U.S. exporter, Boeing supports airlines Form 10-K 9 and U.S. and allied government Non-GAAP Measures 122 customers in more than 150 countries. Our products and tailored services Selected Programs, Products and Services 123 include commercial and military air- craft, satellites, weapons, electronic Shareholder Information 132 and defense systems, launch systems, Board of Directors 133 advanced information and communica- Company Officers 134 tion systems, and performance-based logistics and training. With corporate offices in Chicago, Boeing employs more than 165,000 people across the United States and in more than 65 countries. In addition, our enterprise leverages the talents of hundreds of thousands of skilled people working for Boeing suppliers worldwide. Visit us at boeing. Visit us at boeing. com/investorrelations com/community to to view our annual view our Corporate reports and to find Citizenship Report additional information and other information about our financial about how Boeing is performance and working to improve Boeing business communities world- practices. wide. Cover image: Artist concept of Boeing’s CST-100, the next-generation Visit us at boeing. Visit us at boeing. human-rated space- com to learn more com/environment to craft for NASA’s Crew about Boeing and view our current Transportation Sys- how extraordinary Environment Report tem, shown approach- innovations in our and information on ing the International products and how the people of Space Station. -

October 2014 / Volume XIII, Issue VI

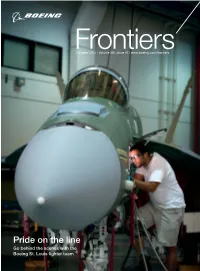

FrontiersOctober 2014 / Volume XIII, Issue VI / www.boeing.com/frontiers Pride on the line Go behind the scenes with the Boeing St. Louis fighter team Frontiers October 2014 01 FRONTIERS STAFF ADVERTISEMENTS Tom Downey The stories behind the ads in this issue of Frontiers. Publisher Brian Ames 03 This new ad features Boeing Commercial Satellite Editorial director Services, a full-service provider of global broadband Paul Proctor connectivity. It appears in trade publications. Executive director James Wallace 11.125 in. Bleed 11.125 in. 10.875 in. Trim 10.875 in. A SECURE CONNECTION Editor Live 10.375 in. FOR SECURE GLOBAL BROADBAND. Vineta Plume Boeing Commercial Satellite Services (BCSS) provides ready access to the secure global broadband you need. Working with industry-leading satellite system operators, including a partnership to provide L- and Ka-band capacity aboard Inmarsat satellites, BCSS offers government and other users an affordable, end-to-end solution Managing editor for secure bandwidth requirements. To secure your connection now, visit www.GoBCSS.com. 7.5 in. Live Cecelia Goodnow 8 in. Trim 8.75 in. Bleed Job Number: BOEG_BDS_CSS_3147M Approved Commercial Airplanes editor Client: Boeing Product: Boeing Defense Space & Security Date/Initials Date: 9/10/14 GCD: P. Serchuk File Name: BOEG_BDS_CSS_3147M Creative Director: P. Serchuk Output Printed at: 100% Art Director: J. Alexander Fonts: Helvetica Neue 65 Copy Writer: P. Serchuk Media: Frontiers Print Producer: Account Executive: D. McAuliffe 3C Space/Color: Page — 4 Color — Bleed 50K Client: Boeing 50C Live: 7.5 in. x 10.375 in. 4C 41M Proof Reader: 41Y Trim: 8 in. -

NOC FALL LISTENING SESSION Metropolitan Airports Commission October 24, 2018 MEETING AGENDA

NOC FALL LISTENING SESSION Metropolitan Airports Commission October 24, 2018 MEETING AGENDA 7:00 Welcome 7:00 Introductions What is your name? Where do you live? What is your goal for this meeting? 7:10 NOC Update 7:20 2019 NOC Work Plan Ideas 8:00 Closing Feedback What did you like / dislike about the meeting format? NOC UPDATE Community Representatives Industry Representatives Minneapolis Scheduled Airlines Richfield Cargo Carrier Bloomington Charter Operator Eagan Chief Pilot Minnesota Business Aviation Mendota Heights Association At-Large Representative At-Large Representative Apple Valley, Burnsville, Edina, Inver Grove Heights, St. Paul, St. Louis Park and Sunfish Lake • NOC viewed as an industry model in reaching collaborative solutions to aircraft noise impacts NOC UPDATE Provide policy recommendations or options to the MAC Planning, Identify, study and analyze Development and Environment airport noise issues Committee and full Commission regarding airport noise issues Ensure the collection of Monitor compliance with information and dissemination to established noise policy at MSP the public NOC UPDATE – 2018 WORK PLAN • Review Residential Noise Mitigation Program • Evaluate Mendota Heights Airport Relations Implementation Status Commission Runway 12L Departure Proposal • Annual Noise Contour Report and Mitigation • Review and respond to MSP FairSkies requests Eligibility • NOC Bylaw Subcommittee Recommendations • Update on the MSP Long Term Comprehensive • Review and discuss Runway Use System priorities Plan and Associated -

Aviation Week & Space Technology

STARTS AFTER PAGE 38 How AAR Is Solving Singapore Doubles Its Workforce Crisis RICH MEDIA Down on Aviation ™ EXCLUSIVE $14.95 FEBRUARY 10-23, 2020 BRACING FOR Sustainability RICH MEDIA EXCLUSIVE Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

Investor Update

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 July 22, 2021 (Date of earliest event reported) ALASKA AIR GROUP, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation) 1-8957 91-1292054 (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 19300 International Boulevard Seattle Washington 98188 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) (206) 392-5040 (Registrant's Telephone Number, Including Area Code) (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. below): ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Ticker Symbol Name of each exchange on which registered Common stock, $0.01 par value ALK New York Stock Exchange Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (17 CFR 230.405) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (17 CFR 240.12b-2). -

FY 2014 R&D Annual Review

FY 2014 R&D Annual Review August 2015 Report of the Federal Aviation Administration to the United States Congress pursuant to Section 44501(c) of Title 49 of the United States Code FY 2014 R&D Annual Review August 2015 The R&D Annual Review is a companion document to the National Aviation Research Plan (NARP), a report of the Federal Aviation Administration to the United States Congress pursuant to Section 44501(c)(3) of Title 49 of the United States Code. The R&D Annual Review is available on the Internet at http://www.faa.gov/go/narp. FY 2014 R&D Annual Review Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 R&D Principle 1 – Improve Aviation Safety ......................................................... 2 R&D Principle 2 – Improve Efficiency ................................................................79 R&D Principle 3 – Reduce Environmental Impacts ..........................................93 Acronym List ........................................................................................................106 i FY 2014 R&D Annual Review List of Figures List of Figures Figure 1: Simulation Validation of GSE Impact Loading on 5-Frame .......................................... 2 Figure 2: Shear Tie Crushing Model Validation............................................................................ 3 Figure 3: Skin Cracking Model Validation ................................................................................... -

Boeing Environment Report 2017

THE BOEING COMPANY 2018 ENVIRONMENT REPORT BUILD SOMETHING CLEANER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover photo: The 737 MAX 7—12 percent more energy efficient than the airplanes it replaces—is the newest member of the 737 MAX family. It began flight testing in 2018. Photo above: Flowers and wind turbines sprout from the Wild Horse Wind and Solar Facility in central Washington State. The Puget Sound Energy facility generates a portion of the electricity that powers Boeing’s 737 factory in Renton, Washington. Renewable energy sources generate 100 percent of the electricity used at the 737 factory and the 787 Dreamliner factory in North Charleston, South Carolina. ABOUT US The commitment is seen in products This report also shares the stories Boeing is the world’s largest and services that deliver market of employees and partners whose leading energy efficiency. In 2017, leadership, creativity and dedication aerospace company. Every Boeing delivered 933 commercial are making a difference in Boeing’s day, through innovation and and military aircraft to customers aspiration to be the best in aerospace across the globe, products that set and an enduring global industrial commitment, the work of more the standard for reductions in fuel champion. use, emissions and community noise. With pride in our accomplishments to than 140,000 employees across The operations of our factories, date and commitment to accelerate the United States and in offices and other facilities in 2017 the progress, Boeing’s goals and surpassed targets for resource strategy will help strengthen the 65 countries is helping build conservation, further improving company’s global environmental our environmental performance leadership and enhance lives and a more sustainable future for and footprint. -

Boeing CLEEN II Briefing

Boeing CLEEN II program update Consortium Public Session Craig Wilsey, Jennifer Kolden May 5, 2021 Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. 1 CLEEN II Technology Demonstrations Agenda Boeing Overview, Sustainability Recap of Boeing’s CLEEN program transitions Boeing CLEEN II Technologies Aft Fan Acoustics Project Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. 2 3 Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. 4 Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. 5 Sustainability Sustainability Strategy CLEEN and ecoDemonstrator programs are Key Elements in Boeing’s Sustainability Portfolio 6 Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. CLEEN II Technology Demonstrations Agenda Boeing Overview, Sustainability Recap of Boeing’s CLEEN program transitions Boeing CLEEN II Technologies Aft Fan Acoustics Project 7 Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. Boeing’s CLEEN Key Demonstrations ATE CMC Nozzle Short Inlet (RR Contract) Flight Test Flight Test Ground Test Support to Short Inlet Flight Test 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 Alt Fuels CMC Nozzle SEW SEW Fan Duct Test Report* Ground Test NIAR Rig Large Acoustics Test Notch Flight Test Test * Supported 2012 ASTM D7566 Specification for “drop-in” blends up to 50% 8 Copyright © 2021 Boeing. All rights reserved. CLEEN I - Adaptive Trailing Edge (ATE) Key Transitions Tested on 2012 ecoDemonstrator Boeing developed and demonstrated a prototype Wing Adaptive Trailing Edge (ATE) system capable of tailoring SMA System Design 777X Baseline Adv Manufacturing and Supply Chain Architecture Smart Shims and wing performance to reduce noise and fuel burn at Standard design Static Trailing Edge related design different flight regimes.