Uttlesford Council Logs Report 2020 (Revised 17-3-20)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 8, Issue 2, June 2009

mag30.qxd 05/05/2009 17:46 Page 1 MAGAZINE OF THE GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION Volume 8 No. 2 June 2009 Appeal for the Archives WSGS Study Tour of Guernsey Meetings July/October ROCKWATCH News Awards Proceedings of the GA Bernard Leake Retires Getting the most from the PGA Dates for your Diary Presidential Address/Lecture Reports GA Trip to Chafford Hundred Book Reviews CIRCULAR 979 mag30.qxd 05/05/2009 17:45 Page 2 Magazine of the Geologists’ Association From the President Volume 8 No.2, 2009 In writing the June presidential report, I am reminded of the vital role that the GA Published by the plays in upholding the importance of geology on a range of scales, from local Geologists’ Association. to international. For example, the GA can serve as a point of contact to provide Four issues per year. CONTENTS critical information on key geological ISSN 1476-7600 sequences that are under threat from 3. The Association insensitive development plans - in short, Production team: JOHN CROCKER, acting as an expert witness. This does Paula Carey, John Cosgrove, New GA Awards not necessarily entail opposing develop- Vanessa Harley, Bill French 4. GA Meetings July/October ment but rather looking for opportunities to enhance geological resources for 5. Awards Printed by City Print, Milton Keynes future study while ensuring that they are 6. Bernard Leake Retires appropriately protected. In addition, a major part of our national earth heritage The GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION 7. Dates for your Diary is preserved within our museums and in does not accept any responsibility for 8. -

Arboricultural Impact Assessment

Arboricultural Impact Assessment For proposed development at: Lavender Cottage, Dellows Lane, Ugley Green, Bishop's Stortford, CM22 6HN Prepared by: Date: Oisin Kelly, Arboricultural Consultant 21st January 2021 E: [email protected] T: 07570 977449 Project Ref: 693 Arborterra Ltd (England & Wales, Company No. 100653051) Registered Office: 12 Bures Road, Great Cornard, Suffolk, CO10 0EJ [email protected] www.arborterra.co.uk Arboricultural Impact Assessment Lavender Cottage, Dellows Lane, Ugley Green, Bishop's Stortford, CM22 6HN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Instructions .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 The Site & Proposal ............................................................................................................. 2 1.3 The Tree Survey ................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Photographs from the tree survey ...................................................................................... 3 2 Impact Assessment ....................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Drawings .............................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Trees to be removed .......................................................................................................... -

85106 Magazine Vol 8

mag31.qxd 17/08/2009 20:08 Page 1 MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF THETHE GEOLOGISTS’GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIAASSOCIATIONTION Volume 8 No. 3 September 2009 FESTIVAL OF GEOLOGY Festival Field Trips Future Lectures Report of Lectures Rockwatch Book Reviews Finds at Portishead Lyme Regis Festival CIRCULAR 980 Tell us about yourself Mole Valley Celebrations Curry Fund support for...... Suttona Antiquior London Quaternary Lectures Bob Stoneley - thanks Pliocene Forest mag31.qxd 12/08/2009 16:19 Page 2 Magazine of the Geologists’ Association From the President Volume 8 No. 3, 2009 Summer is generally a quiet time for Published by the news and therefore an excellent oppor- tunity to get out and about on fieldwork Geologists’ Association. CONTENTS at home or overseas. I have recently become interested in exploring more of Four issues per year. the famous fossil-rich Pleistocene caves ISSN 1476-7600 3. The Association in the south-west of England and have 4. FESTIVAL OF GEOLOGY Production team: JOHN CROCKER, just returned from a couple of weeks 5. Festival Field Trips excavating in a new cave in Somerset Paula Carey, John Cosgrove, 6. Future Lectures where we are finding abundant fossil Vanessa Harley, Bill French 7. Report March/April Lectures material, including wild horse, red deer, mountain hare and many thousands of 8. Rockwatch Printed by City Print, Milton Keynes rodent remains that date to the very 9. Book Review end of the last Ice Age, around 14,500 10. Finds at Portishead years ago. The vertebrate assemblage The GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION Lyme Regis Festival will provide an important means of does not accept any responsibility for 11. -

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

2021 Feb Salings Magazine

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS We are looking out over the last sprinklings of snow as we edit the magazine this month - waiting, like many residents, for warmer weather and the roll-out of the vaccines. Nonetheless, we did see our first snowdrops in Wethersfield Church last week - a promise of better times to come! Normally, of course, we take the opportunity of the editorial to high- light some of the forthcoming events. This has proved a bit difficult at the moment, as we do not know when it will be safe for the govern- ment to relax the COVID-19 restrictions and the ‘stay at home and protect the NHS’ message. This is a particular problem for events like our Fete and Car Display which have a long lead time. Many classic car clubs publish an annu- al calendar of forthcoming events, and we have to decide whether we want to be in it or not. To get round the problem, we have set up a new website dedicated to major forthcoming events in the Salings - stjamesgreatsal- ing.wordpress.com - and decided to tell car clubs that we are plan- ning for an event this year. The website will allow us to update people on changes to plans or specific government restrictions. And with regard to other adverts in the magazine - please phone and check their current status before making a journey! To all our readers, please stay safe, look out for your neighbours and let others know if you need help. Contributions to the next edition by the15th of Feb to: [email protected] 2 From Revd Janet Parker A small booklet and card had been popped through Mary’s door on Christmas morning. -

Oakley Cottage Ugley Green

Oakley Cottage PESTELL & CO Ugley Green ESTATE & LETTING AGENTS Guide Price - £399,995 3 Bedroom, Semi-Detached Cottage Grade II Listed Oakley Cottage:A unique 3 bedroom, semi-detached, Grade II listed cottage set in a picturesque village location. The charming accommodation has been extended and refurbished by the current owners to a high standard and offers original features. Consisting of entrance hallway/vestibule, living room, separate dining room and kitchen/breakfast room, ground floor bathroom, with the 3 bedrooms and en-suite shower room to the master upstairs. To the rear there is an attractive, low maintenance garden and to the front a private driveway for 2/3 vehicles. Walking distance to the mainline train station to Cambridge and London. Stable door into: Entrance Hallway/Vestibule: Carpeted, exposed beams, wall mounted radiator, storage cupboard and 2 ceiling light points, stairs to first floor, door into: Living Room - 11’9 x 11’5 (3.58m x 3.48m) Exposed wooden floorboards and beams, dual aspect windows to front and side, wall mounted radiator, feature fireplace with log burner, brick hearth and wood surround and 2 ceiling light points. Dining Room - 11’4 x 9’ (3.45m x 2.74m) Exposed wooden floorboards and beams, dual aspect windows to front and rear, glazed door to rear, wall mounted radiator and wall lights. 01279 656400 www.pestell.co.uk Outside: To the rear is an attractive low maintenance garden, including large decked area, gravel space and raised borders. Timber storage shed with power, external ‘Combi’ boiler, enclosed by panel fencing and gated access to the front. -

APP/C1570/A/14/2219018 David Lock Associates Ltd Your Ref: Ffp014/Hj 50 North Thirteenth Street Central Milton Keynes 25 August 2016 MK9 3BP

Mr Philip Copsey Our Ref: APP/C1570/A/14/2219018 David Lock Associates Ltd Your Ref: ffp014/hj 50 North Thirteenth Street Central Milton Keynes 25 August 2016 MK9 3BP Dear Sir, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 78 APPEAL BY FAIRFIELD (ELSENHAM) LIMITED ON LAND NORTH EAST OF ELSENHAM, ESSEX APPLICATION REFERENCE UTT/13/0808/OP 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of the Inspector, Mr David Nicholson RIBA IHBC, who held an inquiry on 23-6, 30 September, 1-2, 7-10 and 21-22 October and 23 November 2014 into your client’s appeal against a decision of Uttlesford District Council (‘the Council’) on 26 November 2013 to refuse outline planning permission for application ref: UTT/13/0808/OP, dated 27 March 2013. 2. The development proposed is outline planning permission up to 800 dwellings including uses in Class C3; up to 0.5ha of Class B employment floorspace within Use Class B1a office and B1c light industry; up to 1,400 sq m of retail uses (Class A1/A2/A4/A5); one primary school incorporating early years provision (Class D1); up to 640 sq m of health centre use (Class D1); up to 600 sq m of community buildings (Class D1); up to 150 sq m changing rooms (Class D2); provision of interchange facilities including bus stop, taxi waiting area and drop-off area; open spaces and landscaping (including play areas, playing fields, wildlife habitat areas and mitigation measures, nature park, allotments, reinstated hedgerows, formal/informal open space, ancillary maintenance sheds); -

St Edmund's Area

0 A10 1 9 A Steeple Litlington Little Morden A505 ChesterfordA St Edmund’s College B184 120 A1 Edworth & Prep School Royston Heydon Hinxworth Strethall Ashwell Littlebury Great Old Hall 1039 Chishill Elmdon Saffron A505 B GreenChrishall M11 Walden Astwick Caldecote B1039 DELIVERIES Church End Little Littlebury Therfield Chishill EXIT Green Newnham Wendens B184 A507 Stotfold Slip End Bridge Ambo 10 Duddenhoe Green Bygrave Kelshall Reed End B1052 B1383 Radwell 0 1 Langley A1(M) A10 MAIN A Sandon DELIVERIES Upper Green Langley ENTRANCE Norton B Arkesden Newport Buckland 1 Lower Green Baldock Roe 3 Wallington 6 Green 8 Wicken Mill End Meesden Bonhunt LETCHWORTH Chipping Clavering A5 Widdington Clothall 07 Rickling Willian Rushden Wyddial 9 Starlings Green Throcking Hare B1038 Nurseries Quendon Walsworth Weston Street Brent Pelham Berden M11 HITCHIN Cottered Stocking Henham Hall’s Cromer Buntingford Pelham B1383 Green Ugley Graveley Aspenden Ardeley East End Ugley Green 8 B1037 B1368 Manuden 1 St Westmill A10 105 Ippollytts Walkern Hay Street B Patmore Heath ( ) Wood End Stansted Elsenham A1 M Braughing B656 Clapgate Mountfitchet STEVENAGE Nasty Albury Great Munden Farnham Aston Benington Albury End End Little Haultwick Levens Puckeridge Hadham STANSTED Langley Green BISHOP’S AIRPORT B651 Wellpond 7 Aston Green A120 STORTFORD St Paul’s Dane End Standon Walden INSET Hadham 8 8a A120 Whempstead Ford Bury Green B1256 Takeley A602 Collier’s End Latchford Old Knebworth Street Knebworth Watton B1004 Thorley Street Datchworth at Stone Sacombe A10 -

Cretaceous Intrusions and Rift Features in the Champlain Valley of Vermont

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository New England Intercollegiate Geological NEIGC Trips Excursion Collection 1-1-1987 Cretaceous Intrusions and Rift Features in the Champlain Valley of Vermont McHone, J. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips Recommended Citation McHone, J. Gregory, "Cretaceous Intrusions and Rift Features in the Champlain Valley of Vermont" (1987). NEIGC Trips. 418. https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips/418 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the New England Intercollegiate Geological Excursion Collection at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NEIGC Trips by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B - 5 CRETACEOUS INTRUSIONS AND RIFT FEATURES IN THE CHAMPLAIN VALLEY OF VERMONT J. Gregory Mcflone Department of Geological Sciences University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0059 INTRODUCTION On this field trip we will examine sites near Burlington, Vermont where alkalic dikes and fractures are exposed that could be related to Cretaceous rifting. The setting of these and many similar features is the structural (as opposed to sedimentary) basin of the Lake Champlain Valley, which invites comparison with younger and better-studied continental rifts, such as the Rio Grande Rift of eastern New Mexico or the Gregory Rift of eastern Africa. The validity of such an interpretation depends upon careful study of the tectonic history of the Valley, especially the timing of faulting and its relation to magmatism. The Lake Champlain Valley between Vermont and New York is from 20 to 50 km wide and 140 km long between the northern Taconic Mountains and the Canadian border. -

ESSEX. [KELLY's BEER RETAILERS-Continued

474 BEE ESSEX. [KELLY'S BEER RETAILERS-continued. Gilbey John, I44 High st. Braintree Jagger Wm. Bishop's green, Dunmow Elgie Mrs. S. Broomfi.eld, Chelmsford Gilbey John, Rettendon, Chelmsford James H. W. Gt. Bentley, Colchester Ellis Joshua, Queen's road, Brentwood Godfrey W. 4 Artillery st. Colchester James Z. Carls Colne, Halstead Ellison Mrs. Grace, 36 North hill, Golby William, Wi:x:, Manningtree Jasper Wm. 65 West street, Harwich Colchester Golby William, jun. Stones green, Jeffery E. Elmdon, Saffron Walden Elmer G. R. Northgate st. Colchestr Great Oakley, Harwich Jeffrey .Alfred Smith, Little Walden Ely John Bentley, Cressing, Braintree Golden John, 48 Bridge road, Grays road, Saffron Walden Emberson William, Burton's green, Thurrock, Grays Jennings J. Gt. Leighs, Chelmsford Greenstead green, Halstead Golding Henry, North st. Romford Jennings James, Wood green, Wal- Emmerson Samuel, Woodham Morti- Goldstone Thomas, Cornish Hall End, tham Abbey mer, Maldon Braintree Jennings Robert, Hornchurch, Rmfrd Evans Mrs. C. 59 Parsonage street, Goodaker J. H. 59 North st. Barking Johnson George, The Wash, Hemp- Halstead Goodchild Isaac, Tendring, Colchester stead, Saffron Walden Evans Henry, Collier row, Romford Gould J. Little Holland, Colchester Johnson Jn. Barnston, Chelmsford Evans Mrs. Maria, Uallows green, Graham J. High rd. Loughton S.O Jolinson Mrs. John Roden, Mistley~ .Aldham, Colchester Grange R. 25a, Mnt. Pleasant, Halstd Manningtree Evans William, 5 Trinity sq. Halstead Gray Mrs. H. Fairfield road, Braintree Johnson Mrs. M . .A.. Milton rd.Brentwd Eve "\VaJter, The Wharf, Springfield, Grayling John, Curtis Mill gree:n, Johnstone Mrs. Johanna, Finching- Chelmsford Navestock, Romford field, Braintree Everett G. 6 Anchor st. -

Uttlesford Highways Panel

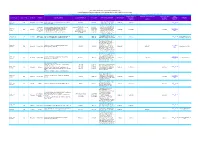

UTTLESFORD LOCAL HIGHWAYS PANEL MEETING AGENDA Date: Monday 29th March 2021 Time: 18:30 Venue: Video Conference Call due to current Covid19 restrictions Chairman: CC Member Simon Walsh Panel Members: CC Member John Moran, CC Member Susan Barker, CC Member Ray Gooding, UDC Member Deryk Eke, UDC Member Geof Driscoll, UDC Member Rod Jones, UDC Member Geoffrey Sell Officers: Essex Highways - Rissa Long, Highway Liaison Officer Essex Highways – Sonia Church, Highway Liaison Manager Essex Highways – Ian Henderson, Senior Road Safety Engineer Secretariat: UDC – Clare Edwards Page Item Subject Lead Paper 1 Welcome & Introductions Chairman Verbal 2 Apologies for Absence Chairman Verbal 3 Minutes of meeting held on 11th January 2021 to be Chairman Verbal 2- 6 agreed as a correct record 4 Matters arising from minutes of previous meeting Chairman Verbal 5 Report on Funded Schemes: Rissa Long Report 1 7 - 10 • 2020/21 11- 23 6 Report on Schemes Awaiting Funding Rissa Long Report 2 7 Any other business: All Verbal 9 Date of next meeting: Chairman Verbal Monday 14th June 2021 at 2pm Monday 27th September 2021at 2pm Monday 17th January 2022 at 2pm Monday 28th March 2022 at 2pm Any member of the public wishing to attend the Uttlesford Local Highways Panel (LHP) must arrange a formal invitation from the Chairman no later than 1 week prior to the meeting. Any public questions should be submitted to the Highway Liaison Officer no later than 1 week before the LHP meeting date; [email protected] 1 UTTLESFORD DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL HIGHWAYS PANEL MINUTES – 11 JANUARY 2021 14:00 HRS VIDEO CONFERENCE CALL Chairman: Councillor Simon Walsh (ECC Member) Panel Members: Councillors Susan Barker (ECC Member), Ray Gooding (ECC Member), John Moran (ECC Member), Geof Driscoll (UDC Member), Deryk Eke (UDC Member), Rod Jones (UDC Member), Geoffrey Sell (UDC Member). -

(The Commons Registration Authority) Index

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Statement Highway Declaration Expiry Date Commons Statement Link to Deeds Reg No. Unique Ref No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION OS GRID REFERENCES POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Deposit Date Deposit Date SUBMITTED REMARKS (PART B) (PART C) (PART D) DEPOSIT Gerald Paul George of The Hall, C/PW To be All of the land being The Hall, Langley Upper Green, Saffron CA16 Form & 1299 Uttlesford Saffron Walden TL438351 CB11 4RZ Langley Upper Green, Saffron 23/07/2021 23/07/2021 allocated. Walden, CB11 4RZ Plan Walden, Essex, CB11 4RZ Ms Louise Humphreys, Webbs Farmhouse, Pole Lane, White a) TL817381 a) Land near Sudbury Road, Gestingthorpe CO9 3BH a) CO9 3BH Notley, Witham, Essex, CM8 1RD; Gestingthorpe, b) TL765197, TL769193, TL768187, b) Land at Witham Road, Black Notley, CM8 1RD b) CM8 1RD Ms Alison Lucas, Russells Farm, C/PW To be Black Notley, TL764189 CA16 Form & 1298 Braintree c) Land at Bulford Mill Lane, Cressing, CM77 8NS c) CM77 8NS Braintree Road, Wethersfield, 15/07/2021 15/07/2021 15/07/2021 allocated. Cressing, White c) TL775198, TL781198 Plan d) Land at Braintree Road, Cressing CM77 8JE d) CM77 8JE Braintree, Essex, CM7 4BX; Ms Notley d) TL785206, TL789207 e) Land