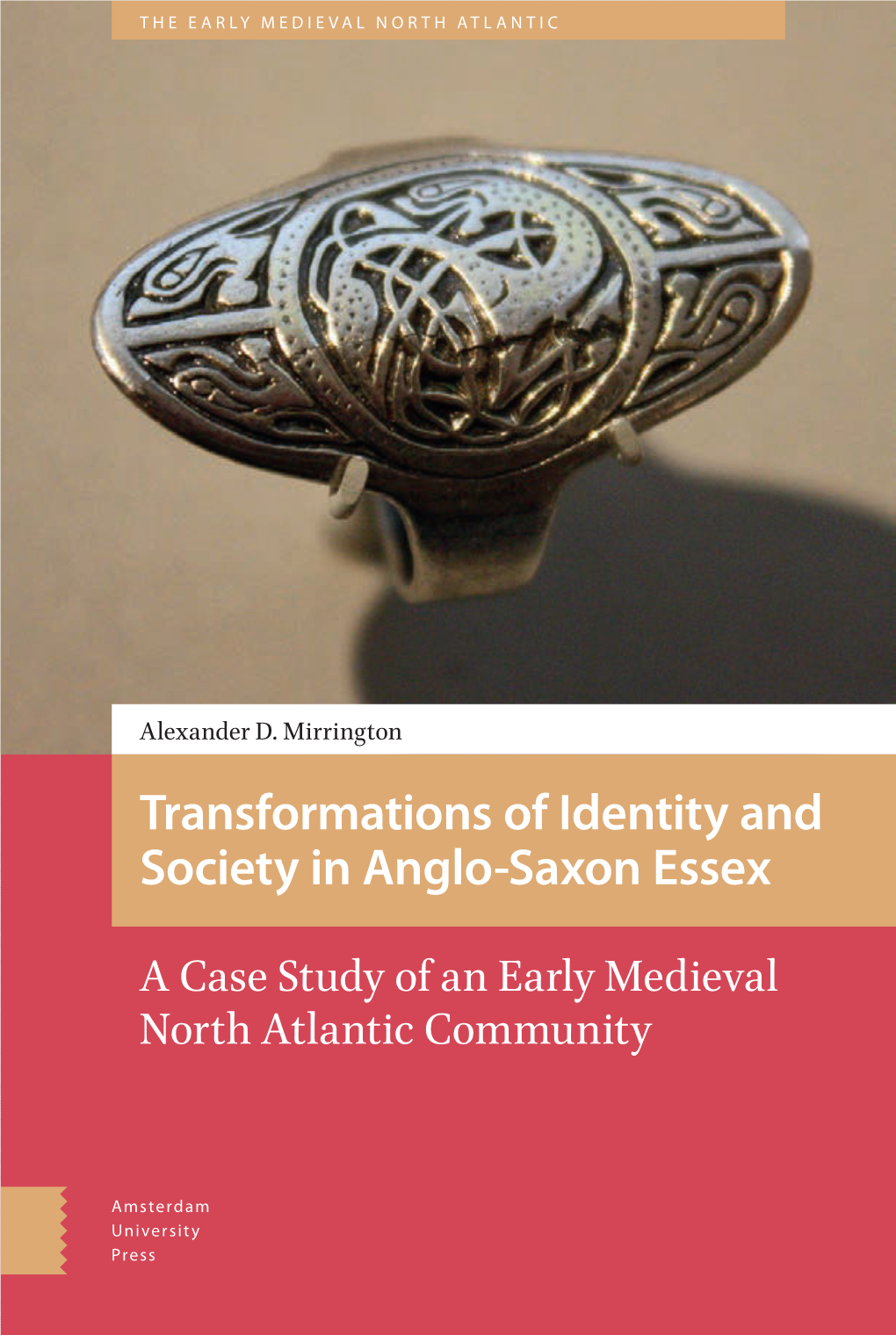

Transformations of Identity and Society in Anglo-Saxon Essex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 8, Issue 2, June 2009

mag30.qxd 05/05/2009 17:46 Page 1 MAGAZINE OF THE GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION Volume 8 No. 2 June 2009 Appeal for the Archives WSGS Study Tour of Guernsey Meetings July/October ROCKWATCH News Awards Proceedings of the GA Bernard Leake Retires Getting the most from the PGA Dates for your Diary Presidential Address/Lecture Reports GA Trip to Chafford Hundred Book Reviews CIRCULAR 979 mag30.qxd 05/05/2009 17:45 Page 2 Magazine of the Geologists’ Association From the President Volume 8 No.2, 2009 In writing the June presidential report, I am reminded of the vital role that the GA Published by the plays in upholding the importance of geology on a range of scales, from local Geologists’ Association. to international. For example, the GA can serve as a point of contact to provide Four issues per year. CONTENTS critical information on key geological ISSN 1476-7600 sequences that are under threat from 3. The Association insensitive development plans - in short, Production team: JOHN CROCKER, acting as an expert witness. This does Paula Carey, John Cosgrove, New GA Awards not necessarily entail opposing develop- Vanessa Harley, Bill French 4. GA Meetings July/October ment but rather looking for opportunities to enhance geological resources for 5. Awards Printed by City Print, Milton Keynes future study while ensuring that they are 6. Bernard Leake Retires appropriately protected. In addition, a major part of our national earth heritage The GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION 7. Dates for your Diary is preserved within our museums and in does not accept any responsibility for 8. -

Charlemagne Empire and Society

CHARLEMAGNE EMPIRE AND SOCIETY editedbyJoamta Story Manchester University Press Manchesterand New York disMhutcdexclusively in the USAby Polgrave Copyright ManchesterUniversity Press2005 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chaptersbelongs to their respectiveauthors, and no chapter may be reproducedwholly or in part without the expresspermission in writing of both author and publisher. Publishedby ManchesterUniversity Press Oxford Road,Manchester 8113 9\R. UK and Room 400,17S Fifth Avenue. New York NY 10010, USA www. m an chestcru niversi rvp ress.co. uk Distributedexclusively in the L)S.4 by Palgrave,175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010,USA Distributedexclusively in Canadaby UBC Press,University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, CanadaV6T 1Z? British Library Cataloguing"in-PublicationData A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7088 0 hardhuck EAN 978 0 7190 7088 4 ISBN 0 7190 7089 9 papaluck EAN 978 0 7190 7089 1 First published 2005 14 13 1211 100908070605 10987654321 Typeset in Dante with Trajan display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow IN MEMORY OF DONALD A. BULLOUGH 1928-2002 AND TIMOTHY REUTER 1947-2002 13 CHARLEMAGNE'S COINAGE: IDEOLOGY AND ECONOMY SimonCoupland Introduction basis Was Charles the Great - Charlemagne - really great? On the of the numis- matic evidence, the answer is resoundingly positive. True, the transformation of the Frankish currency had already begun: the gold coinage of the Merovingian era had already been replaced by silver coins in Francia, and the pound had already been divided into 240 of these silver 'deniers' (denarii). -

85106 Magazine Vol 8

mag31.qxd 17/08/2009 20:08 Page 1 MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF THETHE GEOLOGISTS’GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIAASSOCIATIONTION Volume 8 No. 3 September 2009 FESTIVAL OF GEOLOGY Festival Field Trips Future Lectures Report of Lectures Rockwatch Book Reviews Finds at Portishead Lyme Regis Festival CIRCULAR 980 Tell us about yourself Mole Valley Celebrations Curry Fund support for...... Suttona Antiquior London Quaternary Lectures Bob Stoneley - thanks Pliocene Forest mag31.qxd 12/08/2009 16:19 Page 2 Magazine of the Geologists’ Association From the President Volume 8 No. 3, 2009 Summer is generally a quiet time for Published by the news and therefore an excellent oppor- tunity to get out and about on fieldwork Geologists’ Association. CONTENTS at home or overseas. I have recently become interested in exploring more of Four issues per year. the famous fossil-rich Pleistocene caves ISSN 1476-7600 3. The Association in the south-west of England and have 4. FESTIVAL OF GEOLOGY Production team: JOHN CROCKER, just returned from a couple of weeks 5. Festival Field Trips excavating in a new cave in Somerset Paula Carey, John Cosgrove, 6. Future Lectures where we are finding abundant fossil Vanessa Harley, Bill French 7. Report March/April Lectures material, including wild horse, red deer, mountain hare and many thousands of 8. Rockwatch Printed by City Print, Milton Keynes rodent remains that date to the very 9. Book Review end of the last Ice Age, around 14,500 10. Finds at Portishead years ago. The vertebrate assemblage The GEOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION Lyme Regis Festival will provide an important means of does not accept any responsibility for 11. -

1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King Athelstan’s Sisters and Frankish Queenship Simon MacLean (University of St Andrews) ‘The holy laws of kinship have purposed to take root among monarchs for this reason: that their tranquil spirit may bring the peace which peoples long for.’ Thus in the year 507 wrote Theoderic, king of the Ostrogoths, to Clovis, king of the Franks.1 His appeal to the ideals of peace between kin was designed to avert hostilities between the Franks and the Visigoths, and drew meaning from the web of marital ties which bound together the royal dynasties of the early-sixth-century west. Theoderic himself sat at the centre of this web: he was married to Clovis’s sister, and his daughter was married to Alaric, king of the Visigoths.2 The present article is concerned with a much later period of European history, but the Ostrogothic ruler’s words nevertheless serve to introduce us to one of its central themes, namely the significance of marital alliances between dynasties. Unfortunately the tenth-century west, our present concern, had no Cassiodorus (the recorder of the king’s letter) to methodically enlighten the intricacies of its politics, but Theoderic’s sentiments were doubtless not unlike those that crossed the minds of the Anglo-Saxon and Frankish elite families who engineered an equally striking series of marital relationships among themselves just over 400 years later. In the early years of the tenth century several Anglo-Saxon royal women, all daughters of King Edward the Elder of Wessex (899-924) and sisters (or half-sisters) of his son King Athelstan (924-39), were despatched across the Channel as brides for Frankish and Saxon rulers and aristocrats. -

2020 Nieusj Article

Institutional Repository - Research Portal Dépôt Institutionnel - Portail de la Recherche University of Namurresearchportal.unamur.be RESEARCH OUTPUTS / RÉSULTATS DE RECHERCHE Sigard’s Belt Nieus, Jean-François Published in: Knighthood and Society in the High Middle Ages Author(s) - Auteur(s) : Publication date: 2020 Document Version PublicationVersion created date as- Date part of de publication publication process; : publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Link to publication Citation for pulished version (HARVARD): Nieus, J-F 2020, Sigard’s Belt: The Family of Chocques and the Borders of Knighthood (ca. 9801100). in D PermanentCrouch & link J Deploige - Permalien (eds), Knighthood : and Society in the High Middle Ages: (International Colloquium, Ghent, 10-11 December 2015). vol. 48, Mediaevalia Lovaniensia I. Studia, Leuven University Press, Louvain, pp. 121- 141. Rights / License - Licence de droit d’auteur : General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Cretaceous Intrusions and Rift Features in the Champlain Valley of Vermont

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository New England Intercollegiate Geological NEIGC Trips Excursion Collection 1-1-1987 Cretaceous Intrusions and Rift Features in the Champlain Valley of Vermont McHone, J. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips Recommended Citation McHone, J. Gregory, "Cretaceous Intrusions and Rift Features in the Champlain Valley of Vermont" (1987). NEIGC Trips. 418. https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips/418 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the New England Intercollegiate Geological Excursion Collection at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NEIGC Trips by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B - 5 CRETACEOUS INTRUSIONS AND RIFT FEATURES IN THE CHAMPLAIN VALLEY OF VERMONT J. Gregory Mcflone Department of Geological Sciences University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0059 INTRODUCTION On this field trip we will examine sites near Burlington, Vermont where alkalic dikes and fractures are exposed that could be related to Cretaceous rifting. The setting of these and many similar features is the structural (as opposed to sedimentary) basin of the Lake Champlain Valley, which invites comparison with younger and better-studied continental rifts, such as the Rio Grande Rift of eastern New Mexico or the Gregory Rift of eastern Africa. The validity of such an interpretation depends upon careful study of the tectonic history of the Valley, especially the timing of faulting and its relation to magmatism. The Lake Champlain Valley between Vermont and New York is from 20 to 50 km wide and 140 km long between the northern Taconic Mountains and the Canadian border. -

The Young King and the Old Count: Around the Flemish Succession Crisis of 965

This is a repository copy of The young king and the old count: Around the Flemish succession crisis of 965. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/140885/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McNair, FA (2018) The young king and the old count: Around the Flemish succession crisis of 965. Revue Belge de Philologie et de Histoire, 95 (2). pp. 145-162. ISSN 0035-0818 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Revue Belge de Philologie et de Histoire. Uploaded with permission from the publisher. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Young King and the Old Count: Around the Flemish Succession Crisis of 965 Abstract: In 965, Count Arnulf the Great of Flanders died, leaving a small child as his only heir. In the wake of his death, the West Frankish King Lothar annexed his southern lands for the crown. -

How Much Material Damage Did the Northmen Actually Do to Ninth-Century Europe?

HOW MUCH MATERIAL DAMAGE DID THE NORTHMEN ACTUALLY DO TO NINTH-CENTURY EUROPE? Lesley Anne Morden B.A. (Hons), McGill University, 1982 M.A. History, McMaster University, 1985 M.L. I.S., University of Western Ontario, 1987 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of History O Lesley Morden 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Lesley Anne Moden Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Tiue of Theds: How much material damage did the Northmen actually do to nlnthcenbny Europe? Examining Committee: Chalc Jorwtph Tayior Assodate Professor and CRC. Deparbnent of History, SFU Paul E Dutton Jack and Nancy Farley Endowed Univenr'i Prafessor. t-imanities Department, SFU Courbrey Booker Assistant P*SSOT, Hiory Department. UBC Richard Unger Pmfessor, History Deparbnent UBC John Cdg Professor and Chair of Deparbnent of History Emlly O'Brien wantProfessor. Department of History ABSTRACT HOW MUCH MATERIAL DAMAGE DID THE NORTHMEN ACTUALLY DO TO NINTH-CENTURY EUROPE? Lesley Anne Morden The aim of this dissertation is to examine the material damage the Northmen perpetrated in Northern Europe during the ninth century, and the effects of their raids on the economy of the Carolingian empire. The methodological approach which is taken involves the comparison of contemporary written accounts of the Northmen's destruction to archaeological evidence which either supports these accounts, or not. In the examination of the evidence, the destruction of buildings and settlements, and human losses are taken into account. -

Uttlesford Council Logs Report 2020 (Revised 17-3-20)

Uttlesford District Council Report on Local Geological Sites Prepared for Uttlesford Council by: Gerald Lucy FGS GeoEssex Ros Mercer BSc. GeoEssex Produced: 17th February 2020 Revised: 17th March 2020 Contents 1. Introduction GeoEssex Geodiversity Local and National Geodiversity Action Plans 2. The Geology of Essex Geological map of Essex Essex through geological time 3. Background to Geological Site designation in Uttlesford What is special about Essex geodiversity? Geodiversity’s influence on Essex’s development The geology of Uttlesford district The Ice Age in Uttlesford Sarsens and puddingstones Geodiversity and National Planning Policy Site designations 4. Objectives of current report Supporting local planning authorities 5. Site selection Site selection and notification to planning authorities Site protection Site assessment criteria Land ownership notification 6. Additional Sources of Information 7. List of Geological Sites SSSIs in Uttlesford district LoGS in Uttlesford district Other Sites – potential LoGS Appendix 1: Citations for individual Local Geological Sites (LoGS) approved by the Local Sites Partnership Cover photographs: Top: Road sign at Stansted Mountfitchet indicating the former existence of a nearby chalk pit and lime kiln. Photo: G. Lucy Middle: Limefields Chalk Pit on the Little Walden Road, Saffron Walden. Photo: G. Lucy Bottom: The Leper Stone, Newport. Photo: M. Ralph 2 LoGS report for Uttlesford Council Revised 17 March 2020 1. Introduction The rocks beneath the Essex landscape are a record of the county's prehistory. They provide evidence for ancient rivers, volcanoes, deserts, glaciers and deep seas. Some rocks also contain remarkable fossils, from subtropical sharks and crocodiles to Ice Age hippos and mammoths. The geology of Essex is a story that stretches back over 100 million years. -

Studies in Sixth-Century Gaul

GREGORY OF TOURS AND THE WOMEN IN HIS WORKS Studies in Sixth-Century Gaul Erin Thomas Dailey Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History February, 2011 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that the appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Erin Thomas Dailey iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful for the opportunity to thank all of those who contributed to this study on Gregory of Tours and the women in his works. First I must mention my deep gratitude to my supervisor, Ian Wood, whose kind and eager assistance was invaluable in every part of this project. I must also thank the School of History in the University of Leeds, which not only accepted this project but also provided funding in the form of a generous bursary. Several people have cordially read and commented on this study in part or in total, and so I would like to offer my deepest thanks to Helmut Reimitz, Paul Fouracre, Stephen Werronen, Sheryl McDonald, Carl Taylor, Meritxell Perez Martinez, Michael Garcia, Nicky Tsougarakis, and Henna Iqbal. I must also mention Sylvie Joye, who provided me with several useful materials in French, and Danuta Shanzer, who provided me with her latest research on the Burgundian royal family. -

A Case for Ecclesiastical Minting of Anglo-Viking Coins

A Case for Ecclesiastical Minting of Anglo-Viking Coins Thesis by Joseph Schneider Advised by Professor Warren Brown In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of History CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Background: Coinage in Pre-Viking Anglo-Saxon England ............................................................................ 4 Background: Viking Settlement of England ................................................................................................ 12 Anglo-Viking Coinages: The Question of Ecclesiastical Minting ................................................................. 15 A Survey of Anglo-Viking Coins ................................................................................................................... 21 The Case for Ecclesiastical Coinage ............................................................................................................. 33 The Danelaw Church ................................................................................................................................... 42 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 46 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... -

Sustainable Drainage Systems Design Guide

Sustainable Drainage Systems Design Guide Essex County Council April 2016 SuDS Design Guide (i) Terms of Reference and Composition of SuDS The Working Group comprises ECC Officers: The Steering Group comprises those above Guide Working Group and Steering Group plus additional members representing: Planning & Environment The Working Group, formed to look at pro- Keith Lawson Essex Highways: David Ardley ducing a SuDS Design and Adoption Guide, Phil Callow Environment Agency: Graham Robertson consisted of representatives from various de- Lucy Shepherd Mersea Homes: Brad Davies partments within Essex County Council (ECC), Kathryn Goodyear Bellway Homes : Clive Bell/Ben Ambrose who reflect a range of related disciplines. The Tim Simpson Barratt Homes: Rodney Osborne Steering Group consisted of representatives Persimmon Homes: Terry Brunning from Essex County Council as well as external Development Management, Essex Highways Countryside Properties: Andrew Fisher organisations. The objective of the Groups Vicky Presland Essex Legal Services: Alan Timms was to: Peter Wright Tendring District Council: John Russel Peter Morris Basildon District Council: Matthew Winslow “Develop a Design Guide demonstrating Philip Hughes Epping Forest District Council: Quasim Durrani how new developments can accommodate SuDS, the standards expected of any new Place Services SuDS scheme to be suitable for approval and Crispin Downs adoption, provide an overview of the geology Peter Dawson and biodiversity of the county and advice on how SuDS will be maintained and how they should be ensured to be maintainable.” This has been achieved by: • Reviewing background information and current advice • Collecting suitable case studies within Essex • Considering updates from Defra and the National Standards Consultation • Taking on board comments from restricted and public consultations.