Dean Acheson's Press Club Speech Reexamined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

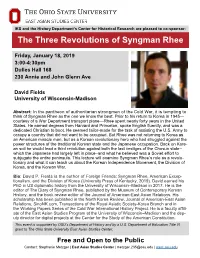

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

The Causes of the Korean War, 1950-1953

The Causes of the Korean War, 1950-1953 Ohn Chang-Il Korea Military Academy ABSTRACT The causes of the Korean War (1950-1953) can be examined in two categories, ideological and political. Ideologically, the communist side, including the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea, desired to secure the Korean peninsula and incorporate it in a communist bloc. Politically, the Soviet Union considered the Korean peninsula in the light of Poland in Eastern Europe—as a springboard to attack Russia—and asserted that the Korean government should be “loyal” to the Soviet Union. Because of this policy and strategic posture, the Soviet military government in North Korea (1945-48) rejected any idea of establishing one Korean government under the guidance of the United Nations. The two Korean governments, instead of one, were thus established, one in South Korea under the blessing of the United Nations and the other in the north under the direction of the Soviet Union. Observing this Soviet posture on the Korean peninsula, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung asked for Soviet support to arm North Korean forces and Stalin fully supported Kim and secured newly-born Communist China’s support for the cause. Judging that it needed a buffer zone against the West and Soviet aid for nation building, the Chinese government readily accepted a role to aid North Korea, specifically, in case of full American intervention in the projected war. With full support from the Soviet Union and comradely assistance from China, Kim Il-sung attacked South Korea with forces that were better armed, equipped, and prepared than their counterparts in South Korea. -

Gendered Rhetoric in North Korea's International

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2015 Gendered rhetoric in North Korea’s international relations (1946–2011) Amanda Kelly Anderson University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Anderson, Amanda Kelly, Gendered rhetoric in North Korea’s international relations (1946–2011), Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2015. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 UNNEGOTIATED TRANSITION . SUCCESSFUL OUTCOME: THE PROCESSES OF DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION IN GREECE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Neovi M, Karakatsanis, B.A., M.A. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. 1 A ccessing the UMIWorld's Information sin ce 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8726661 The quest for a bulwark of anti-Communism: The formation of the Republic of Korea Army officer corps and its political socialization, 1945—1950 Huh, Nam-Sung, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 THE QUEST FOR A BULWARK OF ANTI-COMMUNISM: THE FORMATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA A R M Y OFFICER CORPS AND ITS POLITICAL SOCIALIZATION, 1945-1950 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nam-Sung Huh, B.S., B.A., M.A. -

DOWNLOAD United Korea and the Future of Inter-Korean Politics

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 2 15 September · 2006 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez Special Issue: Research from the USF Master of Arts in Asia Pacific Studies Program John Nelson Editorial Consultants Editor’s Introduction Barbara K. Bundy >>.....................................................................John Nelson 1 Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Richard J. Kozicki Protectionist Capitalists vs. Capitalist Communists: CNOOC’s Failed Unocal Bid In Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Perspective Xiaoxin Wu >>.......................................................... Francis Schortgen 2 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka Bih-hsya Hsieh Economic Reform in Vietnam: Challenges, Successes, and Suggestions for the Future Uldis Kruze >>.....................................................................Susan Parini 11 Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Noriko Nagata United Korea and the Future of Inter-Korean Politics: a Work Already in Progress Stephen Roddy >>.......................................................Brad D. Washington 20 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick A Hard or Soft Landing for Chinese Society? Social Change and the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games >>.....................................................Charles S. Costello III 25 Dashing Out and Rushing Back: The Role of Chinese Students Overseas in Fostering Social Change in China >>...........................................................Dannie LI Yanhua 34 Hip Hop and Identity Politics in Japanese Popular Culture >>.......................................................Cary -

Peace in Israel and Palestine: Moving from Conversation to Implementation of a Two-State Solution

PEACE IN ISRAEL AND PALESTINE: MOVING FROM CONVERSATION TO IMPLEMENTATION OF A TWO-STATE SOLUTION Kenneth L. Lewis, Jr.* I. INTRODUCTION .......................................... 253 R II. PALESTINE IS A STATE EVEN IF THE UNITED NATIONS FAILS TO OFFICIALLY RECOGNIZE PALESTINE AS A STATE ................................................... 255 R III. THE SHELL GAME: MANY NATIONS RECOGNIZE PALESTINE AS STATE, BUT IT REMAINS UNCERTAIN WHETHER PALESTINE HAS A DEFINED TERRITORY AND WHETHER IT IS UNDER THE CONTROL OF ITS OWN GOVERNMENT ........................................... 257 R A. The Boundaries of a Palestinian State, Without Force of Security Council Orders, are Merely Amorphous Talking Points ...................................... 259 R 1. Resolution 242 Should be a Basis for Defining the Boundaries of Israel/Palestine .............. 259 R 2. Resolution 338 is Instructive in its Application of Resolution 242 ............................... 260 R 3. At a Minimum, the Palestinian State Should Include the West Bank and Gaza ............... 262 R * Professor Kenneth L. Lewis, Jr. is a tenured Professor of Law at Nova Southeastern University’s Shepard Broad College of Law. Professor Lewis is an accountant and attorney, and before joining the faculty at Shepard Broad College of Law, he was a chief financial officer for a multi-million dollar corporation, and later worked as attorney with the firm of Greenberg Traurig in Miami, Florida. Professor Lewis is very active in his community, and among other things, he has served as a member of the Lauderhill Regional Chamber of Commerce Board of Directors, an appointed member on the City of Lauderhill’s Affordable Housing Committee, and past President of the City of Lauderhill Youth Soccer Association. Professor Lewis would like to thank his research assistants, Jennifer Bautista and Lauren Matta, for their diligence and exceptional work. -

The State of Deterrence in Korea and the Taiwan Strait for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N MICHAEL J. MAZARR, NATHAN BEAUCHAMP-MUSTAFAGA, TIMOTHY R. HEATH, DEREK EATON What Deters and Why The State of Deterrence in Korea and the Taiwan Strait For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3144 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0400-8 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Keith Anderson Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled What Deters and Why: North Korea and Russia, sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

Politics of Forgetting: New Zealand-Greek Wartime Relationship

Politics of Forgetting: New Zealand-Greek Wartime Relationship Martyn Brown Bachelor of Arts Graduate Diploma Library Science Graduate Diploma Information Technology Post-Graduate Diploma Business Research Master of Arts (Research) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History Philosophy Religion and Classics Abstract In extant New Zealand literature and national public commemoration, the New Zealand experience of wartime Greece largely focuses on the Battle of Crete in May 1941 and, to a lesser extent, on the failed earlier mainland campaign. At a politico-military level, the ill-fated Greek venture and the loss of Crete hold centre stage in the discourse. In terms of commemoration, the Battle of Crete dominates as an iconic episode in the national history of New Zealand. As far as the Greeks are concerned, New Zealand elevates and embraces Greek civilians to the point where they overshadow the Greek military. The New Zealand drive to place the Battle of Crete as supporting its national self-imagining has been achieved, but what has been forgotten in the process? The wartime connection between the Pacific nation and Greece lasted for the remainder of the international conflict and was highly complex and sometimes violent. In occupied Greece and Crete, as well as in the Middle East, North Africa and Italy, New Zealand forces had to interact with a divided Greek nation that had been experiencing ongoing political turmoil and intermittent civil conflict. Individual New Zealanders found themselves acting as liaison officers with competing partisan groups. Greek military units with a history of mutiny and political intrigue were affiliated with the main New Zealand fighting force, the Second New Zealand Division. -

A Tale of Two Koreas: Breaking the Vicious Circle Mark Byung Moon Suh

Perspective & Analysis Focus Asia No. 5 December 2013 A Tale of Two Koreas: Breaking the Vicious Circle Mark Byung Moon Suh This paper traces the history of inter-Korean relations, highlighting that the failure of the ROK and DPRK to recognize each other remains a key obstacle to normal- izing relations and resolving the crisis on the Korean Peninsula. It is argued that unification strategies based on absorption of the other are counterproductive and that without a change in thinking and strategies based on mutual recognition and the establishment of trust, it is impossible to find a lasting peace mechanism to replace the Armistice Agreement. ince 1948 there have existed two states on the Korean Peninsula should be understood in the con- divided Korean Peninsula: North and South text of this abnormal political situation dating back to Korea. Both were recognized as sovereign states more than six decades ago. Sby the UN in 1991, and most countries of the world have normal relations with both Korean states. Only Baptism of Fire: The Birth of Two Koreas the U.S. and Japan do not have normal diplomatic relations with North Korea; Japan has yet to recog- Immediately after the Second World War, on August nize it as a sovereign state. Syria and Cuba do not have 15, 1945, Korea was liberated after 35 years of Japanese official-level relations with South Korea. However, the occupation. It was soon occupied, however, by U.S. real problem, as is examined in this paper, is the fact and Soviet forces, which took control of the southern that the two Korean states still refuse to recognize each and northern parts of the peninsula, respectively.