Institutions As a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

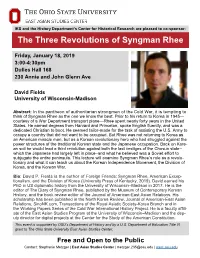

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

Understanding Development and Poverty Alleviation

14 OCTOBER 2019 Scientific Background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2019 UNDERSTANDING DEVELOPMENT AND POVERTY ALLEVIATION The Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel THE ROYAL SWEDISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, founded in 1739, is an independent organisation whose overall objective is to promote the sciences and strengthen their influence in society. The Academy takes special responsibility for the natural sciences and mathematics, but endeavours to promote the exchange of ideas between various disciplines. BOX 50005 (LILLA FRESCATIVÄGEN 4 A), SE-104 05 STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN TEL +46 8 673 95 00, [email protected] WWW.KVA.SE Scientific Background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2019 Understanding Development and Poverty Alleviation The Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel October 14, 2019 Despite massive progress in the past few decades, global poverty — in all its different dimensions — remains a broad and entrenched problem. For example, today, more than 700 million people subsist on extremely low incomes. Every year, five million children under five die of diseases that often could have been prevented or treated by a handful of proven interventions. Today, a large majority of children in low- and middle-income countries attend primary school, but many of them leave school lacking proficiency in reading, writing and mathematics. How to effectively reduce global poverty remains one of humankind’s most pressing questions. It is also one of the biggest questions facing the discipline of economics since its very inception. -

Philippe Aghion

CURRICULUM VITAE (last updated March 2018) Name: Philippe Aghion Address: College de France 3 rue d Ulm 75005 Paris France Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Date of Birth: August 17, 1956 Place of Birth: Paris, France Education: 1976-80 Ecole Normale Supérieure de Cachan, Mathematics Section 1981 Diplome d’Etudes Approfondies d’Economie Mathématique, Université de Paris I 1983 Doctorat de 3éme cycle d’Economie Mathématique, Université de Paris I- Pantheon-Sorbonne 1987 Ph.D. Harvard University (Economics) Professional Experience: 1986-87 Sloan Foundation Dissertation Fellowship 1987-89 Assistant Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1989- Chargé de Recherches au Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique 1990-1992 Deputy Chief Economist, EBRD (London) 1992-96 Official Fellow, Nuffield College (Oxford) 1992-2000 Research Co-ordinator, EBRD (London) 1996-2002 Professor of Economics, University College London (UCL) 2000-2002 Professor of Economics, Harvard University 2002- 2015 Robert C. Waggoner Professor of Economics, Harvard University 2015- Professor at College de France, Chair entitled “Institutions, Innovation, et Croissance” 2009-2015 Invited Professor, Institute of International Economic Studies, Stockholm 2015- Centennial Professor of Economics, London School of Economics 2018-2020 Visiting Professor, Department of Economics, Harvard University Other Professional Positions or Appointments: 1991-97 Associate Editor, Review of Economic Studies 1992- Managing Editor, -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

Investing in Yourself: an Economic Approach to Education Decisions

PAGE ONE Economics the back story on front page economics NEWSLETTER February I 2013 Investing in Yourself: An Economic Approach to Education Decisions Scott A. Wolla, Senior Economic Education Specialist “When I travel around the country, meeting with students, business people, and others interested in the economy, I am occasionally asked for investment advice…I know the answer to the question and I will share it with you today: Education is the best investment.” —Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, September 24, 20071 One of the most important investment decisions you will ever make is the decision to invest in yourself. You might think that investment is only about buying stocks and bonds, but let’s take a step back and consider investment a little differently. Economists use the word investment to refer to spending on capital, which can be either physical capital (tools and equipment) or human capital (education and training). Let’s briefly look at each type. Investing in Physical Capital A firm invests in itself by buying capital that it uses to improve what it does. In other words, it invests in physical capital to earn higher profits in the future. For example, a firm might invest in new technology to increase the productivity of its employees. The increased productivity raises future revenue (income earned by the firm) and profits (revenue minus costs of production). Seems like an easy decision, right? Well, before a firm invests in physical capital, it must consider three very important points. First, a firm invests in technology now with the expectation that it will lead to higher revenue and expected profits in the future. -

Escaping the Climate Trap? Values, Technologies, and Politics∗

Escaping the Climate Trap? Values, Technologies, and Politics Tim Besleyyand Torsten Perssonz November 2020 Abstract It is widely acknowledged that reducing the emissions of green- house gases is almost impossible without radical changes in consump- tion and production patterns. This paper examines the interdependent roles of changing environmental values, changing technologies, and the politics of environmental policy, in creating sustainable societal change. Complementarities that emerge naturally in our framework may generate a “climate trap,”where society does not transit towards lifestyles and technologies that are more friendly to the environment. We discuss a variety of forces that make the climate trap more or less avoidable, including lobbying by firms, private politics, motivated scientists, and (endogenous) subsidies to green innovation. We are grateful for perceptive comments by Philippe Aghion, David Baron, Xavier Jaravel, Bård Harstad, Elhanan Helpman, Gilat Levy, Linus Mattauch, and Jean Tirole, as well as participants in a Tsinghua University seminar, and LSE and Hong Kong University webinars. We also thank Azhar Hussain for research assistance. Financial support from the ERC and the Swedish Research Council is gratefully acknowledged. yLSE, [email protected]. zIIES, Stockholm University, [email protected] 1 1 Introduction What will it take to bring about the fourth industrial revolution that may be needed to save the planet? Such a revolution would require major structural changes in production as well as consumption patterns. Firms would have to invest on a large scale in technologies that generate lower greenhouse gas emissions, and households would have to consume goods that produce lower emissions. Already these observations suggest that the required transformation can be reinforced by a key complementarity, akin to the one associated with so- called platform technologies (Rochet and Tirole 2003). -

Capital Maintenance Concepts in Fair Value

Josipa Mrša, University of Rijeka, Faculty of Economics, Rijeka, Croatia Davor Mance, University of Rijeka, Faculty of Economics, Rijeka, Croatia Davor Vašiček, University of Rijeka, Faculty of Economics, Rijeka, Croatia CONCEPTS OF CAPITAL MAINTENANCE IN FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING Abstract One of the most important information given by accounting is the one concerning company value and the value of its assets, liabilities and equity. The concept of capital maintenance is concerned with how an enterprise defines the capital that it seeks to maintain in profit determination. The concept of fair value accounting is concerned with the valuation of assets, liabilities, and equity based on market values or its closest substitutes. As only inflows in excess of the amounts needed to preserve the capital may be regarded as profit, the choice of the capital maintenance measurement basis influences the residual amount, i.e. the profit, and consequently, the decision-making process. Currently, there are two basic capital maintenance concepts: financial capital maintenance concept and physical capital maintenance concept, each with many variants. Different valuation concepts are not commensurate with any of the theoretical variants of capital maintenance. Keywords: Capital maintenance concepts, fair value accounting, company value, valuation methods, measurement basis. 1. Introduction Modern accounting recognizes several valuation methods and basis of measurement, other than historical cost, that are more closely related to the acceptable economic value at the time of valuation. Currently, there are some nine different valuation methods across the IASs and IFRSs derived from the four basic measurement basis employed in the IASs and IFRSs: historical cost, current cost, realisable (settlement) value, and present value. -

Human Capital Risk, Contract Enforcement, and the Macroeconomy

Human Capital Risk, Contract Enforcement, and the Macroeconomy Tom Krebs, Moritz Kuhn, and Mark L. J. Wright October 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Reserve Federal WP 2014-09 Human Capital Risk, Contract Enforcement, and the Macroeconomy∗ Tom Krebs University of Mannheim† Moritz Kuhn University of Bonn Mark L. J. Wright FRB Chicago and NBER October 2014 Abstract We use data from the Survey of Consumer Finance and Survey of Income Program Participation to show that young households with children are under-insured against the risk that an adult member of the household dies. We develop a tractable macroeconomic model with human capital risk, age-dependent returns to human capital investment, and endogenous borrowing constraints due to the limited pledgeability of human capital (limited contract enforcement). We show analytically that, consistent with the life insurance data, in equilibrium young households are borrowing constrained and under-insured against human capital risk. A calibrated version of the model can quantitatively account for the life-cycle variation of life-insurance holdings, financial wealth, earnings, and consumption inequality observed in the US data. Our analysis implies that a reform that makes consumer bankruptcy more costly, like the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, leads to a substantial increase in the volume of both credit and insurance. Keywords: Human Capital Risk, Limited Enforcement, Life Insurance JEL Codes: E21, E24, D52, J24 ∗We thank seminar participants at various institutions and conferences for useful comments. We especially thank the editor and three referees for many suggestions and insightful comments. Tom Krebs thanks the German Research Foundation for support under grant KR3564/2-1. -

Capital Productivity

Capital Productivity McKinsey Global Institute with assistance from Axel Borsch-Supan and our Advisory Committee Bob Solow, Chairman Ben Friedman Zvi Griliches Ted Hall Washington, D.C. June 1996 Thisreportis copyrightedby McKinsey& Company,Inc.; no part ofit maybe circulated,quoted,or reproducedfor distribution withoutpriorwrittenapprovalfromMcKinsey& Company,Inc.. Preface This reportis an end productof a year-longprojectby theMcKinseyGlobalhstitute (MGI)on capitalproductivityin the threeleadingeconomiesof theworld,Germany,Japan andtheUnited States. Withthis projectwehavecompletedour malysis of themostfmdamentalcomponentsof economicperformanceamongtheleadingeconomies. GDPpercapitais the Singlebest indicator of the overallperformanceof m economy. That outcome,ofcourse,is determinedas theresultof totalfactorproductivitymd the percapitainputsof laborandcapital. PreviousMGI stidies fmsed on laborproductivitylandemploymen~(laborinputs). Thisstidy focuseson capital inputs,capitalproductivityand thecontributionof capitalproductivityto totalfactor productivity. We also wantedto studycapitalproductivitybecauseof the relationbetweencapitalmd saving. Savingis settingasidea partof incomefromcurrentproductionto be usedfor future consumption.Thestoragedeviceis capital. Thus,capitalproductivityis an important determinantof the futurevalueof savings. Savingswerem importanttopicin the MGI projecton capitalmarkets.3Therewe addressedthe increasingsocidburden comingfromthe agingof the industrialcomtries’ populations.h responseto thisburden,retirementbenefitsmustincreasinglybe -

0530 New Institutional Economics

0530 NEW INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS Peter G. Klein Department of Economics, University of Georgia © Copyright 1999 Peter G. Klein Abstract This chapter surveys the new institutional economics, a rapidly growing literature combining economics, law, organization theory, political science, sociology and anthropology to understand social, political and commercial institutions. This literature tries to explain what institutions are, how they arise, what purposes they serve, how they change and how they may be reformed. Following convention, I distinguish between the institutional environment (the background constraints, or ‘rules of the game’, that guide individuals’ behavior) and institutional arrangements (specific guidelines designed by trading partners to facilitate particular exchanges). In both cases, the discussion here focuses on applications, evidence and policy implications. JEL classification: D23, D72, L22, L42, O17 Keywords: Institutions, Firms, Transaction Costs, Specific Assets, Governance Structures 1. Introduction The new institutional economics (NIE) is an interdisciplinary enterprise combining economics, law, organization theory, political science, sociology and anthropology to understand the institutions of social, political and commercial life. It borrows liberally from various social-science disciplines, but its primary language is economics. Its goal is to explain what institutions are, how they arise, what purposes they serve, how they change and how - if at all - they should be reformed. This essay surveys the wide-ranging and rapidly growing literature on the economics of institutions, with an emphasis on applications and evidence. The survey is divided into eight sections: the institutional environment; institutional arrangements and the theory of the firm; moral hazard and agency; transaction cost economics; capabilities and the core competence of the firm; evidence on contracts, organizations and institutions; public policy implications and influence; and a brief summary. -

Endogenous Preferences: the Political Consequences of Economic Institutions

Endogenous Preferences: The Political Consequences of Economic Institutions Jan-Emmanuel De Neve∗y November 5, 2009 Abstract This paper attempts to explain cross-national voting behavior in 18 West- ern democracies over 1960-2003. A new data set for the median voter is intro- duced that corrects for stochastic error in the statistics from the Comparative Manifesto Project. Next, the paper finds that electoral behavior is closely re- lated to the salience of particular economic institutions. Labour organization, skill specificity, and public sector employment are found to influence individual voting behavior. At the country level, this paper suggests that coordinated market economies move the median voter to the left, whereas liberal market economies move the median voter to the right. The empirical analysis employs cross-sectional and panel data that are instrumented with the level of eco- nomic structure circa 1900 to estimate the net effect of economic institutions on the median voter. Significant results show that revealed voter preferences are endogenous to the economic institutions of the political economy. This paper places political economy at the heart of voting behavior and implies the existence of institutional advantages to partisan politics. Keywords: Comparative Political Economy, Median Voter, Voting Behav- ior, Panel Data, Instrumental Variables JEL Classification Numbers: C23, D72, H5, J24, J51, O57, P51 . ∗London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Government, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom (email: [email protected]). yFor their time and generous data sharing, the author would like to thank Simon Hix, Jonathan Hopkin, Peter Hall, Torben Iversen, Lane Kenworthy, Duane Swank, Daniel Gingerich, Pepper Culpepper, Piero Stanig, Slava Mikhaylov, Johannes Spinnewijn, and Richard Fording. -

Employee Representation and Corporate Governance: a Missing Link

EMPLOYEE REPRESENTATION AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE: A MISSING LINK Sanford M. Jacobyt The publication of Freeman and Rogers' What Workers Want' is a major contribution to the debate over employee representation in America. The authors have answered the basic question of what workers and manag- ers want. Now we must reconsider how public policy can be designed to help these preferences be realized. Although Freeman and Rogers have on other occasions contributed ideas for closing the representation gap,2 the present study maintains a curious silence on solutions. Most of the recent policy proposals on employee representation at- tempt to tweak the National Labor Relations Act to permit greater experi- mentation with nonunion employee participation plans. For example, the so-called Dunlop Commission of the mid-1990s outlined the following four principal policy options, all of which focused on labor law: (1) to retain the law in its present form; (2) to revise section 8(a)(2) to permit employers to create employee involvement plans and even company unions, so long as they do not bargain collectively with the employer (the approach contained in the so-called TEAM Act); (3) to modify the TEAM approach to permit employers to establish employee involvement plans but require that they meet certain standards for employee selection, access to information, and protection against reprisals; and (4) to legally require the establishment of employee participation committees,3 as in the plan put forth in 1990 by Professor Paul Weiler to require every company above a certain size to es- tablish elected committees to address the firm's human resource policies t Professor of Management, Policy Studies and History, UCLA; A.B.