CER Bulletin Issue 108 | June/July 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Oral Evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 712 Tuesday 12 January 2016

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 712 Tuesday 12 January 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 12 January 2016 Watch the meeting Members present: Mr Andrew Tyrie (Chair), Sir Paul Beresford, Mr Clive Betts, Crispin Blunt, Andrew Bridgen, Ms Harriet Harman, Meg Hillier, Huw Irranca-Davies, Dr Julian Lewis, Mr Angus Brendan MacNeil, Jesse Norman, Mr Laurence Robertson, Neil Parish, Keith Vaz, Bill Wiggin Questions 1–108 Witness: Rt Hon David Cameron MP, Prime Minister, gave evidence. Q1 Chair: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. Thank you very much for coming to give evidence to the first of the Liaison Committee’s public meetings in this Session. First of all, I want to establish that you are going to continue the practice of the last Parliament and appear three times a Session. Mr Cameron: Yes, if we all agree. I thought last time it worked quite well to have three sessions: one in this bit, one between Easter and summer, and one later in the year. This idea of picking some subjects, to be determined by you, rather than going across the piece—I am happy either way, but I think it worked okay. Q2 Chair: We have a problem for this Session, because we have a bit of a backlog. We tried to get you before Christmas but that was not possible, so we would be very grateful if you could make two more appearances this Session. Mr Cameron: Yes, that sounds right—one between Easter and summer recess, and one— Q3 Chair: I think it will be two before the summer. -

Thecoalition

The Coalition Voters, Parties and Institutions Welcome to this interactive pdf version of The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Please note that in order to view this pdf as intended and to take full advantage of the interactive functions, we strongly recommend you open this document in Adobe Acrobat. Adobe Acrobat Reader is free to download and you can do so from the Adobe website (click to open webpage). Navigation • Each page includes a navigation bar with buttons to view the previous and next pages, along with a button to return to the contents page at any time • You can click on any of the titles on the contents page to take you directly to each article Figures • To examine any of the figures in more detail, you can click on the + button beside each figure to open a magnified view. You can also click on the diagram itself. To return to the full page view, click on the - button Weblinks and email addresses • All web links and email addresses are live links - you can click on them to open a website or new email <>contents The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Edited by: Hussein Kassim Charles Clarke Catherine Haddon <>contents Published 2012 Commissioned by School of Political, Social and International Studies University of East Anglia Norwich Design by Woolf Designs (www.woolfdesigns.co.uk) <>contents Introduction 03 The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Introduction The formation of the Conservative-Liberal In his opening paper, Bob Worcester discusses Democratic administration in May 2010 was a public opinion and support for the parties in major political event. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

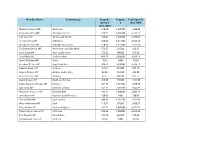

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

The Prime Minister, HC 1393

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: The Prime Minister, HC 1393 Wednesday 18 July 2018 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 18 July 2018. Watch the meeting Members present: Dr Sarah Wollaston (Chair); Hilary Benn; Chris Bryant; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; Mary Creagh; Lilian Greenwood; Sir Bernard Jenkin; Norman Lamb; Dr Julian Lewis; Angus Brendan MacNeil; Dr Andrew Murrison; Neil Parish; Tom Tugendhat. Questions 1-133 Witnesses I: Rt Hon Theresa May, Prime Minister. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Rt Hon Theresa May, Prime Minister. Chair: Good afternoon, and thank you for coming. For those following from outside the room, we will cover Brexit to start with for the first hour, and then we will move on to the subjects of air quality, defence expenditure, the restoration and renewal programme here and, if we have time, health and social care. We will start the session with Hilary Benn, the Exiting the European Union Committee Chair. Q1 Hilary Benn: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. Given the events of the last two weeks, wouldn’t it strengthen your hand in the negotiations if you put the White Paper to a vote in the House of Commons? The Prime Minister: What is important is that we have set out the Government’s position and got through particularly important legislation in the House of Commons. Getting the European Union (Withdrawal) Act on the statute book was a very important step in the process of withdrawing from the European Union. We have published the White Paper, and we have begun discussing it at the EU level. -

Formal-Minutes-Liaison-Committee

House of Commons Liaison Committee Formal Minutes Session 2017–19 Liaison Committee: Formal Minutes 2017–19 1 Formal Minutes of the Liaison Committee, Session 2017–19 MONDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2017 Members present: Hilary Benn Norman Lamb Mr Clive Betts Dr Julian Lewis Chris Bryant Angus Brendan MacNeil Sir William Cash Ian Mearns Damian Collins Mrs Maria Miller Yvette Cooper Nicky Morgan Mary Creagh Robert Neill David T C Davies Neil Parish Frank Field Rachel Reeves Lilian Greenwood Tom Tugendhat Harriet Harman Bill Wiggin Meg Hillier Pete Wishart Mr Bernard Jenkin Dr Sarah Wollaston Helen Jones 1. Declarations of Interests Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix). 2. Election of Chair Dr Sarah Wollaston was called to the Chair. Resolved, That the Chair report her election to the House. 3. Evidence from the Prime Minister The Committee considered this matter. 4. National Policy Statements Sub-Committee Ordered, That a National Policy Statements Sub-Committee be appointed (Standing Order No. 145(6)). Ordered, That Dr Sarah Wollaston and Mary Creagh be members of the National Policy Statements Sub-Committee in addition to those members of the committee who are for the time being members of the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Communities and Local Government, Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2 Liaison Committee: Formal Minutes 2017–19 Transport and Welsh Affairs Committees, and that Dr Sarah Wollaston be Chair of the National Policy Statements Sub-Committee (Standing Order No. 145(7)(a)(ii)). Resolved, That the Sub-Committee recommends that, pursuant to Standing Order No. -

Centre Write Spring 2018

Centre Write Spring 2018 GlobalGlobal giant? giant Tom Tugendhat MP | Baroness Helic | Lord Heseltine | Shanker Singham 2 Contents EDITORIAL A FORCE FOR GOOD? Editor’s note Was and is the UK a force for good Laura Round 4 in the world? Director’s note Kwasi Kwarteng MP and Joseph Harker 11 Ryan Shorthouse 5 The home of human rights Letters to the editor 6 Sir Michael Tugendhat 13 The end of human rights in Hong Kong? FREE TRADING NATION Benedict Rogers 14 A global leader in free trade? Aid to our advantage Shanker Singham 7 The Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP 16 Compass towards the Commonwealth #MeToo on the front line Sir Lockwood Smith 8 Chloe Dalton and Baroness Helic 17 Theresa’s Irish trilemma Constitutional crisis? John Springford 10 Professor Vernon Bogdanor 18 Page 7 Shanker Singham examines the future of UK trade after Brexit Clem Onojeghuo Bright Blue is an independent think tank and pressure group Page 21 The Centre Write for liberal conservatism. interview: Tom Tugendhat MP Director: Ryan Shorthouse Chair: Matthew d’Ancona Board of Directors: Rachel Johnson, Alexandra Jezeph, Diane Banks, Phil Clarke & Richard Mabey Editor: Laura Round brightblue.org.uk Print: Aquatint | aquatint.co.uk Matthew Plummer Design: Chris Solomons CONTENTS 3 Emergency first responder A record to be proud of Strongly soft Theo Clarke 20 Eamonn Ives 30 Damian Collins MP 38 THE CENTRE WRITE INTERVIEW: DEFENCE OF THE REALM TEA FOR TWO Tom Tugendhat MP 21 Acting in Alliance with Lord Heseltine Peter Quentin 31 Laura Round 39 BRIGHT BLUE POLITICS The relevance of our Why I’m a Bright Blue MP deterrence CULTURE The Rt Hon Anna Soubry MP 24 The Rt Hon Julian Lewis MP 32 Film: Darkest Hour Research overview Fighting fit Phillip Box 41 Sam Hall 24 James Wharton 33 The future of war: A history Tamworth Prize winner 2017 Jihadis and justice (Sir Lawrence Freedman) David Verghese 26 Dr Julia Rushchenko 34 Ryan Shorthouse 42 Transparent diplomacy Sticking with the deal Exhibition: Impressionists in London James Dobson 28 Nick King 36 Eamonn Ives 43 Page 17 #MeToo on the front line. -

View Questions Tabled on PDF File 0.16 MB

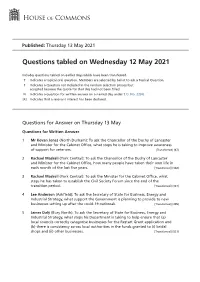

Published: Thursday 13 May 2021 Questions tabled on Wednesday 12 May 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Thursday 13 May Questions for Written Answer 1 Mr Kevan Jones (North Durham): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, what steps he is taking to improve awareness of support for veterans. [Transferred] (87) 2 Rachael Maskell (York Central): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, how many people have taken their own life in each month of the last five years. [Transferred] (342) 3 Rachael Maskell (York Central): To ask the Minister for the Cabinet Office, what steps he has taken to establish the Civil Society Forum since the end of the transition period. [Transferred] (357) 4 Lee Anderson (Ashfield): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, what support the Government is planning to provide to new businesses setting up after the covid-19 outbreak. [Transferred] (445) 5 James Daly (Bury North): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, what steps his Department is taking to help ensure that (a) local councils correctly categorise businesses for the Restart Grant application and (b) there is consistency across local authorities in the funds granted to (i) bridal shops and (ii) other businesses. -

Decision-Making in Defence Policy

House of Commons Defence Committee Decision-making in Defence Policy Eleventh Report of Session 2014–15 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 March 2015 HC 682 Published on 26 March 2015 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rory Stewart MP (Conservative, Penrith and The Border) (Chair) Richard Benyon MP (Conservative, Newbury) Rt Hon Jeffrey M. Donaldson MP (Democratic Unionist, Lagan Valley) Mr James Gray MP (Conservative, North Wiltshire) Mr Dai Havard MP (Labour, Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney) Rt Hon Dr Julian Lewis MP (Conservative, New Forest East) Mrs Madeleine Moon MP (Labour, Bridgend) Sir Bob Russell MP (Liberal Democrat, Colchester) Bob Stewart MP (Conservative, Beckenham) Ms Gisela Stuart MP (Labour, Birmingham, Edgbaston) Derek Twigg MP (Labour, Halton) John Woodcock MP (Labour/Co–op, Barrow and Furness) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in the House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/defcom and by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the Committee’s website on the inquiry page. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are James Rhys (Clerk), Leoni Kurt (Second Clerk), Eleanor Scarnell (Committee Specialist), Ian Thomson (Committee Specialist), Christine Randall (Senior Committee Assistant), Alison Pratt and Carolyn Bowes (Committee Assistants). -

Views Clear, As He Well Knows, When We and Women Being Thrown Out, What Effects Does the Publish the Draft Bill

Tuesday Volume 521 18 January 2011 No. 100 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 18 January 2011 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2011 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 679 18 JANUARY 2011 680 The Deputy Prime Minister: If we needed any House of Commons confirmation, this week of all weeks, that the Labour party’s commitment to cleaning up politics and political reform is a complete and utter farce—the leader of the Tuesday 18 January 2011 Labour party who, sadly, is not in his place, was going around the television studios last weekend saying that The House met at half-past Two o’clock he believed in new politics and that he wanted to reach out to Liberal Democrat voters—it is the dinosaurs in the Labour party in the House of Lords who are PRAYERS blocking people’s ability to have a say on the electoral system that they want. There cannot be meaningful political reform with such weak political leadership. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Duncan Hames (Chippenham) (LD): One hundred years after the temporary provisions of the Parliament Act 1911 were introduced, some of us are impatient for Oral Answers to Questions my right hon. Friend to succeed in achieving an elected second Chamber. Can he reassure me that the grandfathering of voting rights will not be offered to newly appointed peers under the present Government? DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER The Deputy Prime Minister: The specific reference to grandfathering in the coalition agreement applies to the The Deputy Prime Minister was asked— staged way in which we want reform of the House of Lords implemented over time. -

Oral Evidence from the Prime Minister: Brexit, HC 2135

Liaison Committee Oral evidence from the Prime Minister: Brexit, HC 2135 Wednesday 1 May 2019 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 1 May 2019. Watch the meeting Members present: Dr Sarah Wollaston (Chair); Hilary Benn; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; David T. C. Davies; Sir Bernard Jenkin; Dr Julian Lewis; Angus Brendan MacNeil; Sir Patrick McLoughlin; Stephen McPartland; Nicky Morgan; Dr Andrew Murrison; Rachel Reeves. Questions 1-116 Witness I: Rt Hon Theresa May MP, Prime Minister Examination of witness Witness: Rt Hon Theresa May MP. Chair: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. Thank you very much for joining us. Just to set the scene, we thought we would break the discussions about Brexit into three broad groups. The first is taking stock of where we are now, the next stage of negotiations and preparations for no deal. Then we are going to move on to talk about some of the security and border issues. Finally, we will look at trade and the economy. We will then take a break from Brexit and talk about Huawei. We will open with Hilary Benn. Q1 Hilary Benn: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. It has been reported that the Government have cancelled the no-deal Brexit ferry contracts. Is that the case? If so, how much is it going to cost? The Prime Minister: If I can come on to the ferry contracts, I wondered if before I did that it would be helpful if I set the scene, as you are interested in where we are on negotiations and what we are doing.