Decision-Making in Defence Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghan National Security Forces Getting Bigger, Stronger, Better Prepared -- Every Day!

afghan National security forces Getting bigger, stronger, better prepared -- every day! n NATO reaffirms Afghan commitment n ANSF, ISAF defeat IEDs together n PRT Meymaneh in action n ISAF Docs provide for long-term care In this month’s Mirror July 2007 4 NATO & HQ ISAF ANA soldiers in training. n NATO reaffirms commitment Cover Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol n Conference concludes ANSF ready to 5 Commemorations react ........... turn to page 8. n Marking D-Day and more 6 RC-West n DCOM Stability visits Farah 11 ANA ops 7 Chaghcharan n ANP scores victory in Ghazni n Gen. Satta visits PRT n ANP repels attack on town 8 ANA ready n 12 RC-Capital Camp Zafar prepares troops n Sharing cultures 9 Security shura n MEDEVAC ex, celebrations n Women’s roundtable in Farah 13 RC-North 10 ANSF focus n Meymaneh donates blood n ANSF, ISAF train for IEDs n New CC for PRT Raising the cup Macedonian mid fielder Goran Boleski kisses the cup after his team won HQ ISAF’s football final. An elated team-mate and team captain Elvis Todorvski looks on. Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol For more on the championship ..... turn to page 22. 2 ISAF MIRROR July 2007 Contents 14 RC-South n NAMSA improves life at KAF The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their origi- 15 RAF aids nomads nal form. Opinions expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily n Humanitarian help for Kuchis reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

Full List of Her Majesty's Government Correct As of 30 June 2017

Full list of Her Majesty’s Government Correct as of 30 June 2017 Cabinet Also attend Cabinet Foreign and Commonwealth Office Department for Education Department for Communities Department for Work PRIME MINISTER, FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY CHIEF SECRETARY TO THE TREASURY SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND and Local Government and Pensions AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS Rt Hon Theresa May MP Rt Hon Justine Greening MP LORD PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR EUROPE AND THE AMERICAS (MINISTERIAL CHAMPION FOR THE MIDLANDS ENGINE) Rt Hon David Gauke MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE LEADER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS MINISTER OF STATE FOR SCHOOL STANDARDS Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP Rt Hon Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP MINISTER OF STATE FOR EMPLOYMENT Rt Hon Damian Green MP Rt Hon Andrea Leadsom MP Rt Hon Nick Gibb MP MINISTER OF STATE FOR AFRICA MINISTER OF STATE Damian Hinds MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER CHIEF WHIP (PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARY TO THE TREASURY) MINISTER OF STATE Alok Sharma MP Rory Stewart OBE MP (jointly with Department for MINISTER OF STATE FOR DISABLED PEOPLE, HEALTH AND WORK Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP Rt Hon Gavin Williamson CBE MP International Development) Rt Hon Anne Milton MP PARLIAMENTARY UNDER SECRETARY OF STATE Penny Mordaunt MP SECRETARY OF STATE -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Andrew Marr Show 16Th June 2019 Rory Stewart Am

1 RORY STEWART ANDREW MARR SHOW 16TH JUNE 2019 RORY STEWART AM: Welcome. It’s a fairly diverse field at the moment, but nonetheless, if you make it through to the last two that’s two Old Etonians who both went to Balliol College, Oxford, in the last two. It’s hardly diverse. Would the country not be better off choosing, for instance, a Pakistani bus driver’s son? RS: I think you’re right to point to that. I would say by all means focus on the five years that I spent at school, but also look at the five years that I spent in Afghanistan, look at the five years that I spent serving my country in Iraq and in the Balkans, and let’s look at me overall. AM: So your biggest idea in terms of the great big Brexit conundrum facing the country is a citizens’ assembly. This would be chosen sort of randomly by poll. Just explain just exactly how it would work. RS: So two stages: first thing is to get parliament to try to get Brexit through. In the end we live in a parliamentary democracy so we have to begin by convening parliament, and if I’m lucky enough to be elected as leader I would come in with a mandate from the Conservative Party members, the associations of the country, and I could make a different request to Conservative members than the prime minister perhaps was able to in the past. And I would hope also the results of the European elections would make Members of Parliament realise that we need to get Brexit done and get that deal passed. -

Oral Evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 712 Tuesday 12 January 2016

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 712 Tuesday 12 January 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 12 January 2016 Watch the meeting Members present: Mr Andrew Tyrie (Chair), Sir Paul Beresford, Mr Clive Betts, Crispin Blunt, Andrew Bridgen, Ms Harriet Harman, Meg Hillier, Huw Irranca-Davies, Dr Julian Lewis, Mr Angus Brendan MacNeil, Jesse Norman, Mr Laurence Robertson, Neil Parish, Keith Vaz, Bill Wiggin Questions 1–108 Witness: Rt Hon David Cameron MP, Prime Minister, gave evidence. Q1 Chair: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. Thank you very much for coming to give evidence to the first of the Liaison Committee’s public meetings in this Session. First of all, I want to establish that you are going to continue the practice of the last Parliament and appear three times a Session. Mr Cameron: Yes, if we all agree. I thought last time it worked quite well to have three sessions: one in this bit, one between Easter and summer, and one later in the year. This idea of picking some subjects, to be determined by you, rather than going across the piece—I am happy either way, but I think it worked okay. Q2 Chair: We have a problem for this Session, because we have a bit of a backlog. We tried to get you before Christmas but that was not possible, so we would be very grateful if you could make two more appearances this Session. Mr Cameron: Yes, that sounds right—one between Easter and summer recess, and one— Q3 Chair: I think it will be two before the summer. -

Green Conservatism: Protecting the Environment Through Open Markets

Lord Howard of Lympne Toby Lloyd Head of policy, Shelter Peter Franklin Former Conservative policy Guy Newey adviser Head of environment and Rt Hon Greg Barker MP energy, Policy Exchange Minister of state for energy and climate change Dan Byles MP for North Warwickshire Michael Liebreich and Bedworth CEO, Bloomberg New Energy Finance Richard Hebditch George Freeman Campaigns director, MP for Mid Norfolk Campaign for Better Transport Laura Sandys Rory Stewart MP for South Thanet MP for Penrith and the Border Green conservatism: protecting the environment through open markets Green conservatism: © Green Alliance 2013 Green Alliance’s work is licensed protecting the environment through open markets under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No derivative works 3.0 unported Published by Green Alliance, September 2013 licence. This does not replace ISBN 978-1-909980-02-0 copyright but gives certain rights without having to ask Green Alliance for permission. Designed by Howdy and printed by Park Lane Press Under this licence, our work may Edited by Alastair Harper, Hannah Kyrke-Smith and Karen Crane be shared freely. This provides the freedom to copy, distribute and transmit this work on to others, provided Green Alliance is credited This has been published under Green Alliance’s Green Roots as the author and text is unaltered. programme which aims to stimulate green thinking within the This work must not be resold or three dominant political traditions in the UK. Similar collections used for commercial purposes. These conditions can be waived are being published under ‘Green social democracy’ and ‘Green under certain circumstances with liberalism’ projects. -

Rt Hon Rory Stewart OBE MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA 14

Rt Hon Rory Stewart OBE MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA 14 May 2019 Dear Secretary of State, Don’t privatise aid: protect UK aid spending to eradicate global inequalities, not boost profits for British businesses We write to you as members of the UK Fight Inequality Alliance to congratulate you on your appointment, and to set out how we would like to work with you. We are a collective of civil society organisations, trade unions and campaigners who are deeply concerned about the impact of shocking levels of inequality both here in the UK and across the globe, and the current lack of progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Firstly, we would like to take the opportunity to thank you for declaring your commitment to the UK’s 0.7% spend on overseas aid, as well as for identifying climate change as one of DfID’s most important challenges. Nonetheless, the narrative that emerged from your predecessor and a number of other senior politicians continues to cause concern for those of us committed to reducing global inequality. Namely, this is the narrative that promotes “redefining” what is meant by aid in order to allow British businesses to profit from Overseas Development Assistance (ODA). Following the National Audit Office’s report into PFI and PF2, Philip Hammond used this year’s Spring Statement to once again decry the legacy of the Private Finance Initiative and launch a review into the private financing of public services and infrastructure here in the UK. Meanwhile, the Department for International Development (DfID) continues to promote private sector financing as a primary means to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in the global south. -

Thecoalition

The Coalition Voters, Parties and Institutions Welcome to this interactive pdf version of The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Please note that in order to view this pdf as intended and to take full advantage of the interactive functions, we strongly recommend you open this document in Adobe Acrobat. Adobe Acrobat Reader is free to download and you can do so from the Adobe website (click to open webpage). Navigation • Each page includes a navigation bar with buttons to view the previous and next pages, along with a button to return to the contents page at any time • You can click on any of the titles on the contents page to take you directly to each article Figures • To examine any of the figures in more detail, you can click on the + button beside each figure to open a magnified view. You can also click on the diagram itself. To return to the full page view, click on the - button Weblinks and email addresses • All web links and email addresses are live links - you can click on them to open a website or new email <>contents The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Edited by: Hussein Kassim Charles Clarke Catherine Haddon <>contents Published 2012 Commissioned by School of Political, Social and International Studies University of East Anglia Norwich Design by Woolf Designs (www.woolfdesigns.co.uk) <>contents Introduction 03 The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Introduction The formation of the Conservative-Liberal In his opening paper, Bob Worcester discusses Democratic administration in May 2010 was a public opinion and support for the parties in major political event. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

The Heroic Failure of British Leaders

Centro de Estudios y Documentación InternacionalesCentro de Barcelona E-ISSN 2014-0843 B-8438-2012 D.L.: opinión THE HEROIC FAILURE OF BRITISH 581 LEADERS JUNE 2019 Francis Ghiles, Associate Senior Researcher, CIDOB n Tinker Taylor Soldier Spy, John Le Carré offered an acute portrayal of the British establishment’s experience of post-war decline – “Trained to empire, trained to rule the waves. All gone. All taken away. Bye-bye world.” Nostal- Igia for the country’s imperial past is the horror of finding the tables turned. As Fintan O’Toole noted in Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain (London, Head of Zeus, 2018), leaving the European Union is akin to an army retreating to the islands with the spoils, except that large parts of the island, not least Scotland, strongly disagree. One of the most remarkable things about Brexit is the imagi- nary oppression which underlies it. Two weeks ago, during his state visit to London, the US president, Donald Trump, humiliated the British repeatedly, not least by tweeting gratuitous insults about the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan and a patronising attitude to the Prime Min- ister, Teresa May. When he launched his now failed bid for the Tory leadership last week, Dominic Raab stated “we’ve been humiliated as a country”. Observers might have concluded that this was a reaction to President Trump’s insults but such was not the case. His barb was aimed at the European Union. To save nation- al honour demands the country takes the pain of a no-deal Brexit. Newspaper headlines speak of collective abasement –“Humiliating to have to beg” or “Brexit and the prospect of humiliation”, the list is endless. -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

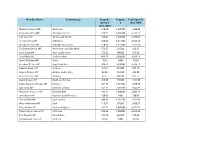

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

Afghanistan Orbats

Coalition Combat Forces in Afghanistan AFGHANISTAN ORDER OF BATTLE by Wesley Morgan January 2013 This document describes the composition and placement of U.S. and other Western combat forces in Afghanistan down to battalion level. It includes the following categories of units: maneuver (i.e. infantry, armor, and cavalry) units, which in most cases are responsible for particular districts or provinces; artillery units, including both those acting as provisional maneuver units and those in traditional artillery roles; aviation units, both rotary and fixed-wing; military police units; most types of engineer and explosive ordnance disposal units; and “white” special operations forces, described in general terms. It does not include “black” special operations units or other units such as logistical, transportation, medical, and intelligence units or Provincial Reconstruction Teams. International Security Assistance Force / United States ForcesAfghanistan (Gen. John Allen, USMC)ISAF Headquarters, Kabul Special Operations Joint Task ForceAfghanistan / NATO Special Operations Component CommandAfghanistan (Maj. Gen. Raymond Thomas III, USA)Camp Integrity, Kabul1 Combined Joint Special Operations Task ForceAfghanistan (USA)Bagram Airfield; village stability operations, advisors to Afghan Defense Ministry special operations forces, and other missions2 Special Operations Task ForceEast (USA)Bagram Airfield; operating in eastern Afghanistan Special Operations Task ForceSouth (USA)Kandahar Airfield; operating in Kandahar Province Special Operations Task ForceSouth-East (USN)U/I location; operating in Uruzgan and Zabul Provinces Special Operations Task ForceWest (USMC)Camp Lawton, Herat; operating in western Afghanistan and Helmand Province TF Balkh / 2-7 Infantry (Lt. Col. Todd Kelly, USA)Camp Mike Spann, Mazar-e-Sharif; operating in northern Afghanistan 3 TF Paktika / 3-69 Armor (Lt.