SELECTION for SMALL and LARGE BODY SIZE in the HOUSE MOUSE”' HE Animal Breeder's Main and Typical Problems Concern Economi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mouse Models of Human Disease an Evolutionary Perspective Robert L

170 commentary Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health [2016] pp. 170–176 doi:10.1093/emph/eow014 Mouse models of human disease An evolutionary perspective Robert L. Perlman* Department of Pediatrics, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5058, Chicago, IL 60637, USA *E-mail: [email protected] Received 31 December 2015; revised version accepted 12 April 2016 ABSTRACT The use of mice as model organisms to study human biology is predicated on the genetic and physio- logical similarities between the species. Nonetheless, mice and humans have evolved in and become adapted to different environments and so, despite their phylogenetic relatedness, they have become very different organisms. Mice often respond to experimental interventions in ways that differ strikingly from humans. Mice are invaluable for studying biological processes that have been conserved during the evolution of the rodent and primate lineages and for investigating the developmental mechanisms by which the conserved mammalian genome gives rise to a variety of different species. Mice are less reliable as models of human disease, however, because the networks linking genes to disease are likely to differ between the two species. The use of mice in biomedical research needs to take account of the evolved differences as well as the similarities between mice and humans. KEYWORDS: allometry; cancer; gene networks; life history; model organisms transgenic, knockout, and knockin mice, have If you have cancer and you are a mouse, we can provided added impetus and powerful tools for take good care of you. Judah Folkman [1] mouse research, and have led to a dramatic increase in the use of mice as model organisms. -

Laboratory Animal Management: Rodents

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/2119 SHARE Rodents (1996) DETAILS 180 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-04936-8 | DOI 10.17226/2119 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Rodents, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council FIND RELATED TITLES SUGGESTED CITATION National Research Council 1996. Rodents. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/2119. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Rodents i Laboratory Animal Management Rodents Committee on Rodents Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C.1996 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Rodents ii National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20418 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. -

A Haplotype Map for the Laboratory Mouse

NEWS AND VIEWS Sample size dictates inference dogma collection, rather than to data generation or ent experimental approaches provides insight The technical revolution that made the cur- analysis. The open question is whether the com- into mechanism and helps specify the genetic rent data boom possible has matured; genetics munity of funding agencies, peer reviewers and model. In fact, genomic convergence is a spe- laboratories now routinely generate millions of regulatory bodies will be prepared to encourage cific embodiment of the concept of ‘consilience genotypes per day. However, more data can be a and support the assembly of subjects and mate- of inductions’, formulated by William Whewell problem when we do not have the discipline to rials needed to accomplish these goals. in the 1840s11, which says that valid inductions apply the scientific method. Replication is also will be supported by data from many different a problem when working with effects so small Candidate gene success experimental approaches. that replication success could not be reasonably Rather than being discovered initially through a Although they benefit greatly from the expected, even if the marker is associated with genome-wide scan of hundreds of thousands of impressive acceleration provided by genome- the disease. genetic markers, which is now the rage, IL7R is wide scans, virtually all genetic association Larger sample size is the mantra of the hour. a candidate gene that refused to quit. Certainly, disease studies ultimately become candidate Experimentalists and funding agencies no longer the first paper on IL7R polymorphisms in mul- gene projects. Additional susceptibility genes in scoff at theoretical analyses showing that thou- tiple sclerosis7 would not have satisfied the strin- multiple sclerosis—siblings of HLA-DRB2, IL7R sands of cases and controls are needed to dem- gent replication criteria advocated by a recent and, probably, IL2RA4—might now stand above onstrate modest genetic associations (Fig. -

Enrichment for Laboratory Zebrafish—A Review of the Evidence and the Challenges

animals Review Enrichment for Laboratory Zebrafish—A Review of the Evidence and the Challenges Chloe H. Stevens *, Barney T. Reed and Penny Hawkins Animals in Science Department, RSPCA, Wilberforce Way, Southwater, West Sussex RH13 9RS, UK; [email protected] (B.T.R.); [email protected] (P.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The zebrafish is one of the most commonly used animals in scientific research, but there remains a lack of consensus over good practice for zebrafish housing and care. One such area which lacks agreement is whether laboratory zebrafish should be provided with environmental enrichment—additions or modifications to the basic laboratory environment which aim to improve welfare, such as plastic plants in tanks. The need for the provision of appropriate environmental enrichment has been recognised in other laboratory animal species, but some scientists and animal care staff are hesitant to provide enrichment for zebrafish, arguing that there is little or no evidence that enrichment can benefit zebrafish welfare. This review aims to summarise the current literature on the effects of enrichment on zebrafish physiology, behaviour and welfare, and identifies some forms of enrichment which are likely to benefit zebrafish. It also considers the possible challenges that might be associated with introducing more enrichment, and how these might be addressed. Abstract: Good practice for the housing and care of laboratory zebrafish Danio rerio is an increasingly discussed topic, with focus on appropriate water quality parameters, stocking densities, feeding Citation: Stevens, C.H.; Reed, B.T.; regimes, anaesthesia and analgesia practices, methods of humane killing, and more. -

Genetic Analysis of Complex Traits in the Emerging Collaborative Cross

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Genetic analysis of complex traits in the emerging Collaborative Cross David L. Aylor,1 William Valdar,1,13 Wendy Foulds-Mathes,1,13 Ryan J. Buus,1,13 Ricardo A. Verdugo,2,13 Ralph S. Baric,3,4 Martin T. Ferris,1 Jeff A. Frelinger,4 Mark Heise,1 Matt B. Frieman,4 Lisa E. Gralinski,4 Timothy A. Bell,1 John D. Didion,1 Kunjie Hua,1 Derrick L. Nehrenberg,1 Christine L. Powell,1 Jill Steigerwalt,5 Yuying Xie,1 Samir N.P. Kelada,6 Francis S. Collins,6 Ivana V. Yang,7 David A. Schwartz,7 Lisa A. Branstetter,8 Elissa J. Chesler,2 Darla R. Miller,1 Jason Spence,1 Eric Yi Liu,9 Leonard McMillan,9 Abhishek Sarkar,9 Jeremy Wang,9 Wei Wang,9 Qi Zhang,9 Karl W. Broman,10 Ron Korstanje,2 Caroline Durrant,11 Richard Mott,11 Fuad A. Iraqi,12 Daniel Pomp,1,14 David Threadgill,5,14 Fernando Pardo-Manuel de Villena,1,14 and Gary A. Churchill2,14 1Department of Genetics, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 2The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, USA; 3Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 4Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 5Department of Genetics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695, USA; 6Genome Technology Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland -

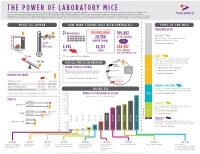

THE POWER of LABORATORY MICE Since the First Published Study Using Mice in 1844, Over 1.4 Million Scholarly Articles Have Been Published

THE POWER OF LABORATORY MICE Since the first published study using mice in 1844, over 1.4 million scholarly articles have been published. Over half of those articles have been published in the past 2 decades and twice as many were published in the decade 2007—2016 than 1997—2006. These data demonstrate the increasing value of laboratory mice in biomedical research. Genetically engineered mice bolstered this growth by improving the ability to translate results to humans. Looking forward, the laboratory mouse will continue to play a critical role in biomedical research, as the ability to generate increasingly precise models will give the researcher of tomorrow an animal that has power to further our understanding of complex human biology. MOUSE VS. HUMAN = HOW MANY STRAINS HAVE BEEN GENERATED? TYPES OF LAB MICE 70 37 °C PERCENTAGE OF USE = 21 REPOSITORIES CRYOPRESERVED 199,892 AVERAGE = = OUTBRED 70 BODY 20,390 ES CELL STRAINS 70 70 37 °C37 °C37 °C 38% Production of offspring from mating of unrelated individuals. TEMPERATURE EMBRYO STRAINS Outbred breeding maintains genetic diversity. AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 AVERAGE AVERAGE AVERAGE Learn more about outbred mice NUMBER OF BODY BODY BODY YEARS TEMPERATURE AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 TEMPERATURETEMPERATURE IN VITRO AVERAGE LIFE SPAN AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 1.5 3,955 26,172 236,927 NUMBER OF NUMBER NUMBEROF OF YEARS LIVE SPERM TOTAL ENTRIES 20 grYEARS YEARS (LIVE, SPERM, EMBRYO, ES CELL) 20 gr20 gr20 gr Source: International Mouse Strain Repository INBRED AVERAGE WEIGHT Production of offspring from mating of male and female mice that are 68AVERAGE kg WEIGHT AVERAGE WEIGHTAVERAGE WEIGHT 68 kg closely related genetically, typically brother x sister mating. -

Chewing and Sucking Lice As Parasites of Iviammals and Birds

c.^,y ^r-^ 1 Ag84te DA Chewing and Sucking United States Lice as Parasites of Department of Agriculture IVIammals and Birds Agricultural Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1849 July 1997 0 jc: United States Department of Agriculture Chewing and Sucking Agricultural Research Service Lice as Parasites of Technical Bulletin Number IVIammals and Birds 1849 July 1997 Manning A. Price and O.H. Graham U3DA, National Agrioultur«! Libmry NAL BIdg 10301 Baltimore Blvd Beltsvjlle, MD 20705-2351 Price (deceased) was professor of entomoiogy, Department of Ento- moiogy, Texas A&iVI University, College Station. Graham (retired) was research leader, USDA-ARS Screwworm Research Laboratory, Tuxtia Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico. ABSTRACT Price, Manning A., and O.H. Graham. 1996. Chewing This publication reports research involving pesticides. It and Sucking Lice as Parasites of Mammals and Birds. does not recommend their use or imply that the uses U.S. Department of Agriculture, Technical Bulletin No. discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesti- 1849, 309 pp. cides must be registered by appropriate state or Federal agencies or both before they can be recommended. In all stages of their development, about 2,500 species of chewing lice are parasites of mammals or birds. While supplies last, single copies of this publication More than 500 species of blood-sucking lice attack may be obtained at no cost from Dr. O.H. Graham, only mammals. This publication emphasizes the most USDA-ARS, P.O. Box 969, Mission, TX 78572. Copies frequently seen genera and species of these lice, of this publication may be purchased from the National including geographic distribution, life history, habitats, Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, ecology, host-parasite relationships, and economic Springfield, VA 22161. -

The Pathogenesis of Spontaneous Autoimmune Peripheral Polyneuropathy: the Nod.B7-2-/- Mouse As a Model for Guillain Barré Syndrome

THE PATHOGENESIS OF SPONTANEOUS AUTOIMMUNE PERIPHERAL POLYNEUROPATHY: THE NOD.B7-2-/- MOUSE AS A MODEL FOR GUILLAIN BARRÉ SYNDROME By Barbie J. Gadsden A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Comparative Medicine and Integrative Biology—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT THE PATHOGENESIS OF SPONTANEOUS AUTOIMMUNE PERIPHERAL POLYNEUROPATHY: THE NOD.B7-2-/- MOUSE AS A MODEL FOR GUILLAIN BARRÉ SYNDROME By Barbie J. Gadsden Guillain Barré Syndrome (GBS) is a symmetrical ascending paralysis that often follows viral or bacterial infection. The foodborne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni is the most common infection that triggers GBS, but C. jejuni is mainly linked to one variant within a complex syndrome: Acute Motor Axonal Neuropathy (AMAN). One third of AMAN patients have IgG autoantibodies against neurogangliosides GM1 and GD1a; binding of these antibodies to peripheral nerves is thought to initiate nerve damage. Other GBS variants include Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (AIDP), Acute Motor and Sensory Axonal Neuropathy (AMSAN), and Miller Fisher Syndrome (MFS). The triggers for these disorders are not known and a large number of potential infectious and noninfectious initiating causes have been implicated. In addition to C. jejuni, bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumonia and Haemophilus influenzae and viruses such as Cytomegalovirus and Influenza have been associated with GBS. GBS disease is monophasic; recurrence is rare, but has been reported. Patients in the initial stages of GBS report headache and joint pain. Tingling and numbness of extremities is followed by segmental ascending paralysis. Pain involving the extremities occurs later in the course of the disease and can be directly correlated with disease severity. -

Rattus Norvegicus and Mus Musculus

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. I Behavioural Ecology of New Zealand Invasive Rodents (Rattus norvegicus and Mus musculus): Implications for Rodent Control A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology at Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand Idan Shapira 2013 II FRONTISPIECE Walter: And let's also not forget… let's not forget, Dude… that keeping wildlife, an amphibious rodent, for uh, domestic, you know, within the city… that isn't legal either. Dude: What're you, a fucking park ranger now? (Ethan and Joel Coen, “The Big Lebowski”) III ABSTRACT Biological invasions are natural phenomena that have occurred throughout the natural history of earth. The highly negative context of the term biological invasion is associated with the fact that many modern invasive processes are anthropogenically driven. Indeed, human affiliated invasions are among the primary drivers of the current biodiversity crises. Murid rodents (Rodentia: Muridea) of the genus Rattus and Mus have become among the worst vertebrate invasive species and apart from man are the most widespread mammals on earth. Invasive rodents have severe and negative effects on human health, agricultural systems, and natural environments. The practice of rodent control is extensive and substantial attempts are made to decrease rodents’ severe impacts on the environment. However, although these attempts are largely successful, there are still issues in the control of invasive rodents and new methodologies, whether at a macro or micro scale are actively pursued. -

EU Directive 2010/63/EU on Protection

Caring for animals aiming for better science DIRECTIVE 2010/63/EU ON PROTECTION OF ANIMALS USED FOR SCIENTIFIC PURPOSES © Novo Nordisk © Novo Environment 1 The publication of "The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique" by W.M.S. Russell and R.L. Burch in 1959 marks the birth of the principles of the “Three Rs”. The authors proposed the principles of Replacement, Reduction and Refinement (the “Three Rs”) as the key strategies aimed at achieving the goal of humane experimental techniques. Russell and Burch saw replacement as the ultimate goal for laboratory animal based research, education and testing, with the other two, reduction and refinement, being more readily achievable in the short term. They summed up their main message as follows: "If we are to use a criterion for choosing experiments to perform, the criterion of humanity is the best we could possibly invent. The greatest scientific achievements have always been the most humane and the most aesthetically attractive, conveying that sense of beauty and elegance which is the essence of science at its most successful." The “Three Rs” in EU legislative framework Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, for the first time in EU legislation spells out the principle of the “Three Rs” and makes it a firm legal requirement in all aspects of care and use of animals in the field. Furthermore, the Directive ensures that its application goes beyond that of the original interpretation also to cover animal breeding and care – that is, to ensure refinement during housing, breeding and care even if the animal is not undergoing a scientific procedure. -

Good Practice for Housing Male Laboratory Mice

animals Review To Group or Not to Group? Good Practice for Housing Male Laboratory Mice Sarah Kappel 1,*, Penny Hawkins 2,* and Michael T. Mendl 1 1 Bristol Veterinary School, Bristol University, Langford House, Langford BS40 5DU, UK; [email protected] 2 Research Animals Department, RSPCA, Wilberforce Way, Southwater, West Sussex RH13 9RS, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (P.H.); Tel.: +44-1403-793-231 (P.H.) Received: 17 October 2017; Accepted: 20 November 2017; Published: 24 November 2017 Simple Summary: Wild mice live in territories inhabited by one adult male, several females, and their offspring. This cannot be replicated in the laboratory, so male mice are usually housed in single-sex groups or individually. However, there can be serious animal welfare problems associated with both these approaches, such as lack of social contact when housed individually or aggression between males when kept in groups. Group housing is widely recommended to give male laboratory mice the opportunity to behave as ‘social animals’, but social stress can be detrimental to the welfare of these animals, even without injurious fighting. All of this can also affect the quality of the science, giving rise to ethical concerns. This review discusses whether it is in the best welfare interests of male mice to be housed in groups, or alone. We conclude that it is not possible to give general recommendations for good practice for housing male laboratory mice, as responses to single- and group-housing can be highly context-dependent. The welfare implications of housing protocols should be researched and considered in each case. -

Routes of Administration R UE of OUTES

C HAPTER32 Routes of Administration R OUTES OF Shinya Shimizu A DMINISTRATION National Institute of Animal Health,Tsukuba, Japan increases successful treatment. Personnel using experi- General mental animals should be well trained in handling and restraint, should obtain authentication for responsible Mice are the most widely used animals for a range of use of experimental animals and attain a scientifically experiments including medical, chemical, pharmaco- high standard (ETS 123, 1986; Nebendahl, 2000). 527 logical, toxicological, biological, and genetic. The Further experience will lead to repeatable and reliable administration of test substances, such as chemical ele- results (see Chapter 31 on Handling and Restraint). P ments, compounds, drugs, antibodies, cells or other During administration mice should be protected ROCEDURES agents, to mice is one of the major methods for evalu- from pain, suffering, distress or lasting harm or at least ating their biological activity. pain and distress shall be kept to a minimum (ETS The route of administration is largely dependent on 123, 1986). Some injections (such as footpad injec- the property of the test substance and the objective of tion) are strongly discouraged and if required must be the experiment. All administration should be performed justified on a case by case basis (CCAC, 2002). with knowledge of the chemical and physical characteris- tics of the substance. All routes have both demerit and merit, such as the absorption, bioavailability and metab- olism of the substance. Consideration should be paid to Principles of the pH, viscosity, concentration, sterility, pyrogenicity, toxicity as well as the existence of hazardous substances. administration A knowledge of available methods and techniques of administration as well as knowledge of the deposition Handling and restraint and fate of the administered substance will help the scien- tist/investigator to select the most appropriate route for Good handling and restraint is the most important her/his purpose.