Jofs 23.1 Liimatainen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boklista 1949–2019

Boklista 1949–2019 Såhär säger vår medlem som har sammanställt listan: ”Det här är en lista över böcker som har getts ut under min livstid och som finns hemma i min och makens bokhyllor. Visst förbehåll för att utgivningsåren inte är helt korrekt, men jag har verkligen försökt skilja på utgivningsår, nyutgivning, tryckår och översättningsår.” År Författare Titel 1949 Vilhelm Moberg Utvandrarna Per Wästberg Pojke med såpbubblor 1950 Pär Lagerkvist Barabbas 1951 Ivar Lo-Johansson Analfabeten Åke Löfgren Historien om någon 1952 Ulla Isaksson Kvinnohuset 1953 Nevil Shute Livets väv Astrid Lindgren Kalle Blomkvist och Rasmus 1954 William Golding Flugornas herre Simone de Beauvoir Mandarinerna 1955 Astrid Lindgren Lillebror och Karlsson på taket 1956 Agnar Mykle Sången om den röda rubinen Siri Ahl Två små skolkamrater 1957 Enid Blyton Fem följer ett spår 1958 Yaşar Kemal Låt tistlarna brinna Åke Wassing Dödgrävarens pojke Leon Uris Exodus 1959 Jan Fridegård Svensk soldat 1960 Per Wästberg På svarta listan Gösta Gustaf-Jansson Pärlemor 1961 John Åberg Över förbjuden gräns 1962 Lars Görling 491 1963 Dag Hammarskjöld Vägmärken Ann Smith Två i stjärnan 1964 P.O. E n q u i st Magnetisörens femte vinter 1965 Göran Sonnevi ingrepp-modeller Ernesto Cardenal Förlora inte tålamodet 1966 Truman Capote Med kallt blod 1967 Sven Lindqvist Myten om Wu Tao-tzu Gabriel García Márques Hundra år av ensamhet 1968 P.O. E n q u i st Legionärerna Vassilis Vassilikos Z Jannis Ritsos Greklands folk: dikter 1969 Göran Sonnevi Det gäller oss Björn Håkansson Bevisa vår demokrati 1970 Pär Wästberg Vattenslottet Göran Sonnevi Det måste gå 1971 Ylva Eggehorn Ska vi dela 1972 Maja Ekelöf & Tony Rosendahl Brev 1 År Författare Titel 1973 Lars Gustafsson Yllet 1974 Kerstin Ekman Häxringarna Elsa Morante Historien 1975 Alice Lyttkens Fader okänd Mari Cardinal Orden som befriar 1976 Ulf Lundell Jack 1977 Sara Lidman Din tjänare hör P.G . -

Låna En Bokcirkel Stadsbiblioteket Facebook-Square Twitter 5 Exemplar

Opium för folket/serieantologi Som jag minns det/Mikael Persbrandt Pappaklausulen/Jonas Hassen Khemiri Sommarboken/Tove Jansson Pennskaftet/Elin Wägner Stoner/John Williams Pojkflickan/Nina Bouraoui Stål/Silvia Avallone Pottungen/Anna Laestadius Larsson Ställ ut en väktare/Harper Lee Ru/Kim Thúy Svart fjäril/Anna Jansson Räfvhonan/Anna Laestadius Larsson Swede Hollow/Ola Larsmo Samlade dikter/Edith Södergran Sörja för de sina/Kristina Sandberg Sankmark/Jhumpa Lahiri Till minne av en villkorslös kärlek/ Jonas Gardell Sarahs nyckel/Tatiana de Rosnay Tisdagarna med Morrie/Mitch Albom Sargassohavet/Jean Rhys Tjänarinnans berättelse/Margaret Atwood Serien om Alberte/Cora Sandel Twist/Klas Östergren Simma med de drunknade/ Lars Mytting Vera/Anne Swärd Sista brevet från din älskade/ Vi kom över havet/Julie Otsuka Jojo Moyes Vredens druvor/John Steinbeck Skynda att älska/Alex Schulman Väggen/Marlen Haushofer Slutet på kedjan/Fredrik T. Olsson Yarden/Kristian Lundberg Små eldar överallt/Celeste Ng Återstoden av dagen/Ishiguro Små ögonblick av lycka/ Hendrik Groen Vad handlar böckerna om? Vill du ha fler titlar? Nya titlar kommer till hela tiden. Sök på ”bokcirkel- påse” i katalogen på vår hemsida så hittar du alla påsar och kan läsa mer om vad böckerna i dem handlar om. Lämna gärna inköpsförslag till ditt bibliotek! Låna en bokcirkel Stadsbiblioteket facebook-square twitter 5 exemplar. 60 dagars lånetid. Näbbtorgsgatan 12, 019–21 61 10, [email protected] Prenumerera på bibliotekets nyhetsbrev: bibliotek.orebro.se/nyhetsbrev Photo by Vincenzo Malagoli from Pexels. Örebro kommun Kultur- och fritidsförvaltningen [email protected] 2019 FOTO: ÖREBRO BIBLIOTEK PRODUKTION: ÖREBRO BIBLIOTEK bibliotek.orebro.se Titel och författare 438 dagar : vår berättelse om stor- Den vidunderliga kärlekens historia/ Fjärilseffekten/Karin Alvtegen Katitzi ; & Katitizi och Swing/ politik, vänskap och tiden som diktatu- Carl-Johan Vallgren Katarina Taikon rens fångar / Johan Persson och Martin Fyren mellan haven/M. -

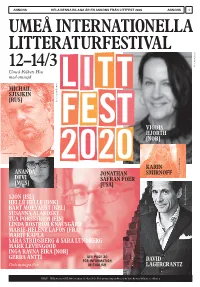

Littfest-Program2020-Web.Pdf

ANNONS HELA DENNA BILAGA ÄR EN ANNONS FRÅN LITTFEST 2020 ANNONS 1 UMEÅ INTERNATIONELLA LITTERATURFESTIVAL 12–14/3 Anette Brun Foto: Umeå Folkets Hus med omnejd MICHAIL SJISJKIN [RUS] Frolkova Jevgenija Foto: VIGDIS HJORTH [NOR] KARIN ANANDA JONATHAN SMIRNOFF Gunséus Johan Foto: Obs! Biljetterna till Littfest 2020 är slutsålda.se sidan För X programpunkter som inte kräver biljett, DEVI SAFRAN FOER [MUS] [USA] Foto: Foto: Timol Umar SJÓN [ISL] HELLE HELLE [DNK] Caroline Andersson Foto: BART MOEYAERT [BEL] SUSANNA ALAKOSKI TUA FORSSTRÖM [FIN] LINDA BOSTRÖM KNAUSGÅRD MARIE-HÉLÈNE LAFON [FRA] MARIT KAPLA SARA STRIDSBERG & SARA LUNDBERG MARK LEVENGOOD INGA RAVNA EIRA [NOR] GERDA ANTTI SEE PAGE 30 FOR INFORMATION DAVID Foto: Jeff Mermelstein Jeff Foto: Och många fler… IN ENGLISH LAGERCRANTZ IrmelieKrekin Foto: OBS! Biljetterna till Littfest 2020 är slutsålda. För programpunkter som inte kräver biljett, se sidan 4 Olästa e-böcker? Odyr surf. Har du missat vårens hetaste boksläpp? Med vårt lokala bredband kan du surfa snabbt och smidigt till ett lågt pris, medan du kommer ikapp med e-läsningen. Vi kallar det för odyr surf – och du kan lita på att våra priser alltid är låga. Just nu beställer du bredband för halva priset i tre månader. Odyrt och okrångligt = helt enkelt oslagbart! Beställ på odyrsurf.se P.S. Är du redan prenumerant på VK eller Folkbladet köper du bredband för halva priset i tre månader. Efter kampanjperioden får du tio kronor rabatt per månad på ordinarie bredbandspris, så länge du är prenumerant. ANNONS HELA DENNA BILAGA ÄR EN -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

C.A. Gottlund Ja Kansanmusiikki

Erkki Pekkilä C.A. GOTTLUND JA KANSANMUSIIKKI Jos halutaan tutkia kansanmusiikin historiaa, voidaan menetellä kahdella tavalla. Voidaan etsiä uusia dokumentteja, jotka valaisisivat sitä mistä ei tähän asti ole tiedetty tai voidaan turvautua vanhoihin dokumentteihin mutta tulkita niitä uudelleen, antaa niille uusia merkityksiä. Valittiin kumpi tie hyvänsä, molemmat vaativat dokumentteja - nuotteja, käsi kirjoituksia, piirroksia, maalauksia, valokuvia, äänitteitä - sillä doku mentit luovat pohjan niille väittärnille, joita menneisyyden tapahtumista tehdään. Ellei ole dokumentteja, ei myöskään ole perusteita väittämille ja ellei ole perusteita, ei ole historiallista "totuutta". Ilman dokumentteja historiasta voidaan esittää vain arvailuja, mikä sitten taas ei ole histo riankiIjoitusta; tällaisilla arveluilla on pelkästään mielipidearvo. Kansanmusiikin paradoksi on, että se ei jätä itsestään dokumentteja. "Aito" kansanmusiikki eli kansanmusiikki sellaisena, miksi se sanakirja määritelmissä käsitetään, on muistinvaraista perinnettä. Muistinvarainen perinne taas on häviävää: ellei sitä tallenneta, sen olemassaolo lakkaa. Tietysti perinnetuotteen olemassaolo saattaa jatkua sillä että se välittyy sukupolvelta toiselle. Samalla tuote kuitenkin kokee muutoksia, eikä nykyhetkenä kerätyn tuotteen iästä ja historiasta voida esittää muuta kuin arveluja. Jälkipolvien onneksi kansanmusiikkia kuitenkin on tallennettu: kansansävelmiä on kerätty, soittimia säilötty museoihin, kansanmusiikin harjoittamisesta kirjoitettu kuvauksia, soittajia valokuvattu. -

Examensarbete Mall

Kandidatuppsats i litteraturvetenskap I skuggan av Augustprisets vinnare - eller den kollektiva silvermedaljen Författare: Tellervo Rajala Handledare: Alfred Sjödin Examinator: Peter Forsgren Termin: VT16 Ämne: Litteraturvetenskap Nivå: Kandidatuppsats Kurskod: 2LI10E Innehåll 1 Inledning ____________________________________________________________ 1 2 Syfte _______________________________________________________________ 1 3 Bakgrund ___________________________________________________________ 2 4 Teori _______________________________________________________________ 4 5 Metod ______________________________________________________________ 6 6 Litteraturgenomgång _________________________________________________ 8 7 Översikt av recensenternas värderingar __________________________________ 9 7.1 Värderingarna 2015 _______________________________________________ 9 7.1.1 Aris Fioreto Mary _____________________________________________ 9 7.1.2 Carola Hansson Masja ________________________________________ 10 7.1.3 Jonas Hassen Khemiri Allt jag inte minns _________________________ 10 7.1.4 John Ajvide Lindqvist Rörelsen. Den andra platsen __________________ 10 7.1.5 Agneta Pleijel Spådomen. En flickas memoarer _____________________ 11 7.1.6 Stina Stoors Bli som folk _______________________________________ 11 7.2 Värderingarna 2014 ______________________________________________ 11 7.2.1 Ida Börjel Ma _______________________________________________ 11 7.2.2 Carl-Michael Edenborg Alkemistens dotter ________________________ 12 7.2.3 Lyra Ekström Lindbäck -

Matkailijan Juva 2020

Matkailijan Juva 2020 Makuja Elämyksiä Historiaa Järviluontoa GOTTLUND- VIIKKOViikon mittainen sukellus paikalliseen historiaan – nykypäivän menoa unohtamatta. Kansanrunouden kerääjänä tunnettu suomen kielen lehtori GOTTLUND-WEEK ja suomalaisuusmies, Carl A week-long celebration of Axel Gottlund, myös Kaarle local culture. All events and Axel Gottlund (1796–1875), lectures are held in Finnish. kasvoi Juvalla kirkkoher- ran poikana. Hän keräsi jo Carl Axel Gottlund (1796-1875), nuorena koti pitäjän kan- a Finnish linguist and folklorist, sanperinnettä ja kannatti spent his childhood in Juva kirjakielenkehittämisessä where he developed an early itämurteita, erityisesti sa- interest in Finnish language volaismurteita. Kansanruno- and culture. As a young man uden ohella hän kirjoitti myös he collected a large number kansanmusiikkia, kantelesävel- of local folk poems and songs miä ja paimensoitinmusiikkia. from Juva region. Katso Gottlund-viikon rento ohjelma osoitteesta juva.fi/kulttuuri Lauantaina 27.6. klo 10–14 JUVAN Kotieläinpiha Taikaniemen KESÄKARKELOT Keskusta ympäristöineen täyttyy iloisesta Farmi markkinahumusta ja tapahtumista. Tule Taikaniemeen tapaamaan Juvan kesäkarkelot (27th June) maatiloilta tuttuja eläimiä, A fun and vibrant annual event in the tilalla tapaat myös laama- centre of Juva brings locals and visitors herrat Eskon ja Jussin! Kotieläin- together to celebrate the best of Finnish summer. Family -friendly entertainment, piha avataan kesällä 2020. summer market and local products. Tuhkalantie 655, Nuutilanmäki +358 406 526 865 [email protected] www.taikaniemi.fi SU 7.6. Miesten superpesistä PE-LA PE Puistolan Sinisellä Laguunilla PE 24.-25.4. 8.5. Kitee vs. Siilinjärvi 7. 8. Touko- SuJuvat Hyötyyn sointuja- Suhinat- SU 28.6. Vattu- tapahtuma tapahtuma Naisten superpesistä karnevaalit Puistolan Sinisellä Laguunilla Lappeenranta vs. -

The Finnish of Rautalampi and Värmland – a Comparison

TORBJÖRN SÖDER Uppsala University The Finnish of Rautalampi and Värmland – A comparison Abstract In this paper some of the features of the Finnish spo ken in the former greatparish1 of Rautalampi and Värmland are discussed. These two Finnish varieties are, owing to their com mon historical background, closely affiliated, both being defined as Eastern Finnish Savo dialects. These varieties were isolated from each other for hundreds of years and the circumstances of the two speech communities are in many respects different. The language contact situation in Värmland involves Swedish varie ties and Värmland Finnish but limited contact with other Finnish varieties. The contact situation in what once was the greatparish of Rautalampi involves mainly Finnish varieties, both dialects and Standard Finnish. Social and economic circumstances have also had an effect on the contact situations, especially since the 19th century when Finland was separated from Sweden and in dustrialization made its definite entrance into both areas. The dif fering language contact situations have in some respects yielded different results. This paper provides examples of the differences, which have occurred as an effect of the circumstances in Rau talampi and in Värmland. I provide examples from the phonologi cal, morphological, lexical, and syntactic levels and discuss them in light of the language contact situation in these areas. Keywords Värmland Finnish, Rautalampi Finnish, Finnish dialects, language contact, language change 1. In this paper, the term “greatparish” is used as an equivalent to Fi. suurpitäjä and Swe. storsocken, which both literally mean ‘large parish’. It refers to a geo graphically large parish which once was established as the result of new settlements in a previously sparsely inhabited area. -

Intersections of Neoliberalism, Race, and Queerness in the Works of Jonas Hassen Khemiri and Ruben Östlund

Challenging Swedishness: Intersections of Neoliberalism, Race, and Queerness in the Works of Jonas Hassen Khemiri and Ruben Östlund by Christian Mark Gullette A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Haverty Rugg, Chair Professor Mark Sandberg Professor Mel Y. Chen Spring 2018 © Christian Mark Gullette 2018 Abstract Challenging Swedishness: Intersections of Neoliberalism, Race, and Queerness in the Works of Jonas Hassen Khemiri and Ruben Östlund by Christian Mark Gullette Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Haverty Rugg, Chair This dissertation explores the work of author Jonas Hassen Khemiri and filmmaker Ruben Östlund, examining the ways both artists consistently negotiate racial identification and “Swedishness” in neoliberal economic contexts that are often at odds with other Swedish, exceptionalist discourses of social justice. Khemiri and Östlund represent contrasting perspectives and tonalities, yet both artists identify the successful competition for capital as a potentially critical component in achieving access to “Swedishness.” Khemiri and Östlund recognize that race and economics are intertwined in neoliberal arguments, even in Sweden, something their works help to elucidate. The implications of such similar observations from very different artists might go overlooked if discussed in isolation. I argue that it is crucial to analyze the negotiation of identity in these works not merely in abstract economic terms, but through their use of a very specific neoliberal economic discourse. -

Miten Kansasta Tulee Vernakulaari?

Artikkelit https://doi.org/10.30666/elore.89069 Miten kansasta tulee vernakulaari? Kansanrunoudentutkimuksen, kirjallisuushistorian ja kansankirjoittajien tutkimuksen kansakuva 1820-luvulta 2010-luvulle Niina Hämäläinen, Kati Mikkola, Ilona Pikkanen ja Eija Stark ernakulaarin käsitettä on viime vuosina alettu käyttää enenevässä määrin ilmiöistä, joita aiemmin on kuvattu kansankielisiksi, kansanomaisiksi tai kansankulttuuriksi. Tämä heijasteleeV syvällisempää muutosta aiemmin kansaksi määriteltyjen tai siihen tiiviisti kytkey- tyvien monimuotoisten tutkimuskohteiden, mutta myös tiettyjen tutkimusalojen luonteen ymmärtämisessä. Mahdollisia syitä vernakulaarin käyttöön tutkimuskirjallisuudessa ja tutki- joiden analyyttisenä työkaluna voi etsiä kansaan liittyvistä poliittisista ja ideologisista kon- notaatioista. Erityisen merkittäviä kansan ja kansallisen sisältöjen historiallisia määrittäjiä ovat olleet humanistisiin aloihin kuuluneet tieteet ja erityisesti historiaa, kieltä ja kulttuuria tutkivat oppialat, joilla pitkälti vakiinnutettiin kansa- ja kansakunta-diskurssit. Tarkastelemme artikkelissamme kansan ja vernakulaarin käsitteiden käyttöä pitkällä aika- välillä seuraavien kysymysten avulla: 1) Millä tavoilla kansan olemusta ja sen toimijuutta on määritelty ja (usein) rajoitettu oppineiston käymissä kansanperinteeseen ja kirjallisuushis- toriaan kytkeytyvissä keskusteluissa1? Miten käsitettä kansa ja sen johdannaisia on käytetty ennen niin sanottua vernakulaarin käännettä? 2) Miten kansanomaisen rinnalle tai tilalle ilmestyy tietyissä -

Inför LP2 Ht 2007 2Rok

ateljé Z AAH131 Ht 2007 Inför LP2 Ht 2007 Ska alla • läsa en roman som utgör en av utgångspunkterna för läsperiodens huvudövning. (Se i gruppindelningen nedan vilken roman var och en ska läsa. Tips: Läs under dataveckan så blir romanläsningen ett trevligt komplement till skärmarbetet.) • samla ihop material om två boendereferenser (sen nedan). 2RoK Det här läsåret kommer ateljéundervisningen att vara inriktad på temat bostad. Vi kommer genom ritningsarbete, analyser, litteraturstudier och modellbygge att komma i kontakt med många olika aspekter på hur vi bor och hur vi utformar bostäder. Under läsperiod två inleder vi med uppgiften 2RoK som är en kombinerad modell-/analysövning. Som ett komplement till övningen kommer vi att ha en övning där vi diskuterar referenser till boende. Inför övningen ska ni läsa utdelad text, samt ha skaffat två boendereferenser (se nedan). Uppgiften 2RoK är uppdelad i tre moment I, II och III, där det andra momentet innehåller delgenomgång och byte av lägenheter. Under större delen av läsperioden (hela övningen 2RoK) kommer ni att arbeta i grupper om två. Jag har komponerat grupper på grundval av den (speciellt när det gäller ettorna, mycket ofullständiga) kunskap jag har om era styrkor och svagheter, med förhoppningen att gruppmedlemmarna ska stötta och komplettera varandra. En ambition för tvåorna har också varit att ”röra om lite i grytan” och skapa nya samarbets- och kontaktytor. Kom ihåg att olja och vinäger kan bli en jättebra dressing tillsammans, även om vätskorna inte blandas. På grund av samordning med delmomentet ”Skissen som redskap” blandas inte ettor och tvåor i grupperna denna gång. Gruppindelning A06 läser arbetar med Anna och Maria K-H Vilhelm Moberg, Utvandrarna Öland, Parstuga, 1800-tal (ca första tredjedelen) Beatriz och Hannes Kerstin Ekman, Springkällan Malmö, St. -

Pirkko Forsman Svensson

Twenty Years of Old Literary Finnish – from Manual to Computer-Assisted Research1 Until fairly recently, research on old Finnish was either based on original texts, or on facsimiles, microfilms and similar sorts of copies in the so-called Old Fennica collection at the University Library of Helsinki. Since the early 1990s, KOTUS, i.e. the Research Institute for the Languages of Finland in Helsinki (http://www.kotus.fi/)2 has been transferring its materials to computer files, thereby making computer-assisted research possible. As of March 2003, the computerized corpora available for researchers other than the Institute's own staff comprise some 17 million Finnish words.3 The commands of the Institute’s Unix system can be used for processing data in the corpora, but several additional search programmes are also available for researchers; agrep is used for searching approximate character strings, kwic for creating KWIC indexes, and segrep for searching character strings in defined text structures. Today the Centre uses the Unix system exclusively, having recently discarded the Open VMS system that was previously used parallel to Unix. The Institute’s Finnish corpus is divided into four sub-groups; (1) Old Literary Finnish (1540—1810), approx. 2.8 million words. (2) 19th Century Finnish (1810—1900), approx. 4 million words.4 (3) Modern Finnish consists of dictionaries (a Dictionary of Modern Finnish from 1966, completed with a glossary of neologisms from the 50s, 60s and 70s, as well as a Basic Dictionary of Finnish in three parts, published in 1990, 1992 and 1994, respectively); a text bank of Finnish from the1990s, and a data base of some 100,000 word entries with an annual increase of approx.