Download (5Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habemus Papam

Fandango Portobello presents a Sacher Films, Fandango and le Pacte production in collaboration with Rai and France 3 Cinema HABEMUS PAPAM a film by Nanni Moretti Running Time: 104 minutes International Fandango Portobello sales: London office +44 20 7605 1396 [email protected] !"!1!"! ! SHORT SYNOPSIS The newly elected Pope suffers a panic attack just as he is due to appear on St Peter’s balcony to greet the faithful, who have been patiently awaiting the conclave’s decision. His advisors, unable to convince him he is the right man for the job, seek help from a renowned psychoanalyst (and atheist). But his fear of the responsibility suddenly thrust upon him is one that he must face on his own. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !"!2!"! CAST THE POPE MICHEL PICCOLI SPOKESPERSON JERZY STUHR CARDINAL GREGORI RENATO SCARPA CARDINAL BOLLATI FRANCO GRAZIOSI CARDINAL PESCARDONA CAMILLO MILLI CARDINAL CEVASCO ROBERTO NOBILE CARDINAL BRUMMER ULRICH VON DOBSCHÜTZ SWISS GUARD GIANLUCA GOBBI MALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST NANNI MORETTI FEMALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST MARGHERITA BUY CHILDREN CAMILLA RIDOLFI LEONARDO DELLA BIANCA THEATER COMPANY DARIO CANTARELLI MANUELA MANDRACCHIA ROSSANA MORTARA TECO CELIO ROBERTO DE FRANCESCO CHIARA CAUSA MASTER OF CEREMONIES MARIO SANTELLA CHIEF OF POLICE TONY LAUDADIO JOURNALIST ENRICO IANNIELLO A MOTHER CECILIA DAZZI SHOP ASSISTANT LUCIA MASCINO TV JOURNALIST MAURIZIO MANNONI HALL PORTER GIOVANNI LUDENO GIRL AT THE BAR GIULIA GIORDANO BARTENDER FRANCESCO BRANDI BOY AT THE BUS LEONARDO MADDALENA PRIEST SALVATORE MISCIO DOCTOR SALVATORE -

Commedia O Dramma? Conta La Realtà a Brancaleone Da Norcia O a Pep- Pe «Er Pantera», Non Ci Servirebbe Solo a Farci Due Risate Con Loro

Colore: Composite ----- Stampata: 11/07/01 21.54 ----- Pagina: UNITA - NAZIONALE - 19 - 12/07/01 giovedì 12 luglio 2001 in scena 19 Il cinema italiano sarà alla ribalta IL TELEFONO, LA SUA VOCE fino a11'11 settembre a Lilla, nel Roberto Gorla nord della Francia. La rassegna è promossa da Plan Guardate le fragole, o i pomodori, una volta bastava il invece e a pagamento, ad uno spot di due ore e mezzo a cellulare è diventato un ricettacolo di sms pubblicitari. proditoriamente il tuo tempo e la tua attenzione ad Sequence, associazione regionale tempo di portarli a casa per ritrovarseli già così am- favore di quel certo orologio, che guardachecaso!, era Che fare per tutti quelli la cui sensibilità non è in ogni angolo di strada t'invita invece gentilmente a casa per la promozione del cinema, in maccati che se non si era lesti a cucinarli li si doveva disseminato nel film come prezzemolo in cucina? Persi- grado di tollerare la Pubblicità se non in dosi modera- sua perché ha delle cose da dirti? C'è stato un tempo in collaborazione con l'Istituto buttare. Oggi, fateci caso, escono da un mese di frigori- no la Pubblicità che non fa pubblicità va guardata con te? Potranno sempre leggersi un libro in santa pace? cui la pubblicità veniva attesa ogni sera come uno Italiano di Cultura di Lilla. Già in fero come un minatore da un mese di vacanza. Un sospetto: George Clooney si presta a fare da testimone Illusi, la Pubblicità è lì che li aspetta a pagine spalanca- spettacolo da non perdere. -

It 2.007 Vc Italian Films On

1 UW-Madison Learning Support Services Van Hise Hall - Room 274 rev. May 3, 2019 SET CALL NUMBER: IT 2.007 VC ITALIAN FILMS ON VIDEO, (Various distributors, 1986-1989) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Italian culture and civilization; Films DESCRIPTION: A series of classic Italian films either produced in Italy, directed by Italian directors, or on Italian subjects. Most are subtitled in English. Individual times are given for each videocassette. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours for previewing purposes or to show them in class. See the Media Catalog for film series in other languages. AUDIENCE: Students of Italian, Italian literature, Italian film FORMAT: VHS; NTSC; DVD CONTENTS CALL NUMBER Il 7 e l’8 IT2.007.151 Italy. 90 min. DVD, requires region free player. In Italian. Ficarra & Picone. 8 1/2 IT2.007.013 1963. Italian with English subtitles. 138 min. B/W. VHS or DVD.Directed by Frederico Fellini, with Marcello Mastroianni. Fellini's semi- autobiographical masterpiece. Portrayal of a film director during the course of making a film and finding himself trapped by his fears and insecurities. 1900 (Novocento) IT2.007.131 1977. Italy. DVD. In Italian w/English subtitles. 315 min. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. With Robert De niro, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. Epic about friendship and war in Italy. Accattone IT2.007.053 Italy. 1961. Italian with English subtitles. 100 min. B/W. VHS or DVD. Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini's first feature film. In the slums of Rome, Accattone "The Sponger" lives off the earnings of a prostitute. -

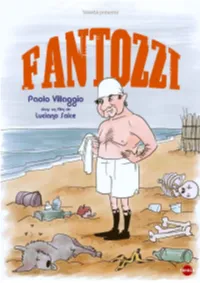

Ce N'est Pas À Moi De Dire Que Fantozzi Est L'une Des Figures Les Plus

TAMASA présente FANTOZZI un film de Luciano Salce en salles le 21 juillet 2021 version restaurée u Distribution TAMASA 5 rue de Charonne - 75011 Paris [email protected] - T. 01 43 59 01 01 www.tamasa-cinema.com u Relations Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] - 06 10 37 16 00 Fantozzi est un employé de bureau basique et stoïque. Il est en proie à un monde de difficultés qu’il ne surmonte jamais malgré tous ses efforts. " Paolo Villaggio a été le plus grand clown de sa génération. Un clown immense. Et les clowns sont comme les grands poètes : ils sont rarissimes. […] N’oublions pas qu’avant lui, nous avions des masques régionaux comme Pulcinella ou Pantalone. Avec Fantozzi, il a véritablement inventé le premier grand masque national. Quelque chose d’éternel. Il nous a humiliés à travers Ugo Fantozzi, et corrigés. Corrigés et humiliés, il y a là quelque chose de vraiment noble, n’est-ce pas ? Quelque chose qui rend noble. Quand les gens ne sont plus capables de se rendre compte de leur nullité, de leur misère ou de leurs folies, c’est alors que les grands clowns apparaissent ou les grands comiques, comme Paolo Villaggio. " Roberto Benigni " Ce n’est pas à moi de dire que Fantozzi est l’une des figures les plus importantes de l’histoire culturelle italienne mais il convient de souligner comment il dénonce avec humour, sans tomber dans la farce, la situation de l’employé italien moyen, avec des inquiétudes et des aspirations relatives, dans une société dépourvue de solidarité, de communication et de compassion. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Vittorio Gassman

VITTORIO GASSMAN 20 anni fa, il 29 giugno 2000 ci lasciava Vittorio Gassman attore, regista, sceneggiatore e scrittore italiano, attivo sia in campo teatrale che cinematografico. È uno dei più importanti e più rappresentativi attori italiani, ricordato per l'assoluta professionalità, per la versatilità e il magnetismo. La mediateca lo ricorda con una selezione delle sue interpretazioni. Film : - VITTORIO RACCONTA GASSMAN di Giancarlo Scarchilli, Documentario, 2010 - AMLETO di Vittorio Gassman, Teatro, 2008 - GASSMAN LEGGE DANTE. DIVINA COMMEDIA di Rubino Rubini, Documentario, 2005 - LA CENA di Ettore Scola, 1998 - SLEEPERS di Barry Levinson, 1996 - ROSSINI! ROSSINI! di Mario Monicelli, 1991 - DIMENTICARE PALERMO di Francesco Rosi, 1990 - LO ZIO INDEGNO di Franco Brusati, 1989 - LA FAMIGLIA di Ettore Scola, 1987 - LA VITA È UN ROMANZO di Alain Resnais, 1983 - LA TERRAZZA di Ettore Scola, 1980 - CARO PAPÀ di Dino Risi, 1979 - QUINTET di Robert Altman, 1979 - UN MATRIMONIO di Robert Altman, 1978 - I NUOVI MOSTRI di Mario Monicelli, Dino Risi e Ettore Scola, 1977 - IL DESERTO DEI TARTARI di Valerio Zurlini, 1976 - SIGNORE E SIGNORI, BUONANOTTE di Leonardo Benvenuti, Luigi Comencini, Piero De Bernardi, Agenore Incrocci, Nanni Loy, Ruggero Maccari, Luigi Magni, Mario Monicelli, Ugo Pirro, Furio Scarpelli e Ettore Scola, 1976 - TELEFONI BIANCHI di Dino Risi, 1976 - C'ERAVAMO TANTO AMATI di Ettore Scola, 1974 - PROFUMO DI DONNA di Dino Risi, 1974 - BRANCALEONE ALLE CROCIATE di Mario Monicelli, 1970 - IL TIGRE di Dino Risi, 1967 - L'ARCIDIAVOLO di Ettore Scola, 1966 - L'ARMATA BRANCALEONE di Mario Monicelli, 1966 - LA CONGIUNTURA di Ettore Scola, 1965 - SLALOM di Luciano Salce, 1965 - SE PERMETTETE PARLIAMO DI DONNE di Ettore Scola, 1964 - I MOSTRI di Dino Risi, 1963 - LA MARCIA SU ROMA di Dino Risi, 1962 - IL SORPASSO di Dino Risi, 1962 - FANTASMI A ROMA di Antonio Pietrangeli, 1961 - CRIMEN di Mario Camerini, 1960 - IL MATTATORE di Dino Risi, 1960 - LA GRANDE GUERRA di Mario Monicelli, 1959 - I SOLITI IGNOTI di Mario Monicelli, 1958 - KEAN. -

The Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti

From Page to Screen: the Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti Lucia Di Rosa A thesis submitted in confomity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) Graduate Department of ltalian Studies University of Toronto @ Copyright by Lucia Di Rosa 2001 National Library Biblioth ue nationale du Cana2 a AcquisitTons and Acquisitions ef Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeOingtOn Street 305, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Otiawa ON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive ~~mnettantà la Natiofliil Library of Canarla to Bibliothèque nation& du Canada de reprcduce, loan, disûi'bute or seil reproduire, prêter, dishibuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format é1ectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, From Page to Screen: the Role of Literatuce in the Films af Luchino Vionti By Lucia Di Rosa Ph.D., 2001 Department of Mian Studies University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation focuses on the role that literature plays in the cinema of Luchino Visconti. The Milanese director baseci nine of his fourteen feature films on literary works. -

William A. Seiter ATTORI

A.A. Criminale cercasi Dear Brat USA 1951 REGIA: William A. Seiter ATTORI: Mona Freeman; Billy DeWolfe; Edward Arnold; Lyle Bettger A cavallo della tigre It. 1961 REGIA: Luigi Comencini ATTORI: Nino Manfredi; Mario Adorf; Gian Maria Volont*; Valeria Moriconi; Raymond Bussires L'agente speciale Mackintosh The Mackintosh Man USA 1973 REGIA: John Huston ATTORI: Paul Newman; Dominique Sanda; James Mason; Harry Andrews; Ian Bannen Le ali della libert^ The Shawshank Redemption USA 1994 REGIA: Frank Darabont ATTORI: Tim Robbins; Morgan Freeman; James Whitmore; Clancy Brown; Bob Gunton Un alibi troppo perfetto Two Way Stretch GB 1960 REGIA: Robert Day ATTORI: Peter Sellers; Wilfrid Hyde-White; Lionel Jeffries All'ultimo secondo Outlaw Blues USA 1977 REGIA: Richard T. Heffron ATTORI: Peter Fonda; Susan Saint James; John Crawford A me la libert^ A nous la libert* Fr. 1931 REGIA: Ren* Clair ATTORI: Raymond Cordy; Henri Marchand; Paul Olivier; Rolla France; Andr* Michaud American History X USA 1999 REGIA: Tony Kaye ATTORI: Edward Norton; Edward Furlong; Stacy Keach; Avery Brooks; Elliott Gould Gli ammutinati di Sing Sing Within These Walls USA 1945 REGIA: Bruce H. Humberstone ATTORI: Thomas Mitchell; Mary Anderson; Edward Ryan Amore Szerelem Ung. 1970 REGIA: K‡roly Makk ATTORI: Lili Darvas; Mari T*r*csik; Iv‡n Darvas; Erzsi Orsolya Angelo bianco It. 1955 REGIA: Raffaello Matarazzo ATTORI: Amedeo Nazzari; Yvonne Sanson; Enrica Dyrell; Alberto Farnese; Philippe Hersent L'angelo della morte Brother John USA 1971 REGIA: James Goldstone ATTORI: Sidney Poitier; Will Geer; Bradford Dillman; Beverly Todd L'angolo rosso Red Corner USA 1998 REGIA: Jon Avnet ATTORI: Richard Gere; Bai Ling; Bradley Whitford; Peter Donat; Tzi Ma; Richard Venture Anni di piombo Die bleierne Zeit RFT 1981 REGIA: Margarethe von Trotta ATTORI: Jutta Lampe; Barbara Sukowa; RŸdiger Vogler Anni facili It. -

Hiol 20 11 Fraser.Pdf (340.4Kb Application/Pdf)

u 11 Urban Difference “on the Move”: Disabling Mobil- ity in the Spanish Film El cochecito (Marco Ferreri, 1960) Benjamin Fraser Introduction Pulling from both disability studies and mobility studies specifically, this ar- ticle offers an interdisciplinary analysis of a cult classic of Spanish cinema. Marco Ferreri’s filmEl cochecito (1960)—based on a novel by Rafael Azcona and still very much an underappreciated film in scholarly circles—depicts the travels of a group of motorized-wheelchair owners throughout urban (and rural) Madrid. From a disability studies perspective, the film’s focus on Don Anselmo, an able-bodied but elderly protagonist who wishes to travel as his paraplegic friend, Don Lucas, does, suggests some familiar tropes that can be explored in light of work by disability theorists.1 From an (urbanized) mobil- ity studies approach, the characters’ movements through the Spanish capital suggest the familiar image of a filmic Madrid of the late dictatorship, a city that was very much culturally and physically “on the move.”2 Though not un- problematic in its nuanced portrayal of the relationships between able-bodied and disabled Madrilenians, El cochecito nonetheless broaches some implicit questions regarding who has a right to the city and also how that right may be exercised (Fraser, “Disability Art”; Lefebvre; Sulmasy). The significance of Ferreri’s film ultimately turns on its ability to “universalize” disability and connect it to the contemporary urban experience in Spain. What makes El cochecito such a complex film—and such a compelling one—is how a nuanced view of (dis)ability is woven together with explicit narratives of urban modernity and implicit narratives of national progress. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

“Breve Século XX” Segundo O Cinema De Carlo Lizzani Gabriela Kvacek Betella

IV Encontro Nacional de Estudos da Imagem I Encontro Internacional de Estudos da Imagem 07 a 10 de maio de 2013 – Londrina-PR Momentos decisivos da história da Itália no “breve século XX” segundo o cinema de Carlo Lizzani Gabriela Kvacek Betella 1 Resumo: Carlo Lizzani é um dos mais profícuos homens de cinema formados durante o neorrealismo italiano, período de breve duração e controvertido, porém de extrema importância como impulso moral no cinema italiano. Nos filmes aqui estudados, ressaltamos a busca do diretor pela ação corálica, a temática popular disposta a relembrar os anos de Resistência e a preocupação com o indivíduo que viveu os anos do fascismo, itens caros para uma poética situada no limite entre a percepção histórica e a visão excessivamente emocional do passado. Para demonstrar a vocação da filmografia do diretor para o panorama histórico do período que vai do final do século XIX e praticamente todo o século XX, destacamos Cronache di poveri amanti (Carlo Lizzani, 1953) e Fontamara (Carlo Lizzani, 1978), analisando-os na perspectiva do discurso histórico revisitado com vistas sobre o cotidiano, os pequenos fatos do passado recuperados no presente da criação. Os filmes mapeiam os anos de 1920 e o impacto do regime fascista tanto no contexto citadino quanto no ambiente rural. Assim, o microcosmo de uma rua de Firenze e um vilarejo na região de Abruzzo, cujas tramas têm origem em duas obras literárias, compõem a visão de Lizzani sobre os primeiros anos do fascismo, trazendo à tona um olhar humanizado sobre os problemas passados e presentes. Palavras-chave: Cinema italiano; Carlo Lizzani; cinema e história Abstract: Carlo Lizzani is one of the most fruitful men of cinema formed during the Italian neorealism, period of short duration and controversial nature, but of high importance as a moral impulse in the Italian cinema.