Park Dissertation for Defense & Submission Mar17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

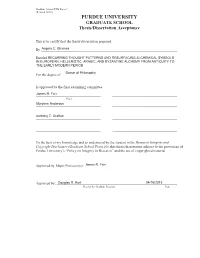

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

La Mummia Nelle Farmacopee Medioevali

F. Lugli – La mummia nelle farmacopee medievali Cultural Anthropology 67 - 70 La mummia nelle farmacopee medioevali Lugli Federico* Abstract. Le mummie non sono solamente corpi umani imbalsamati sopravvissuti allo scorrere del tempo ma appartengono anche al mondo della storia della medicina in quanto utilizzate come medicinale a partire dall'Età Medievale. Sono state sfruttate come rimedio ad un elevato numero di patologie e hanno ricoperto il ruolo di baluardo della scienza medica sino alla fine del XIX secolo. Molti autori antichi hanno trattato della mummia nelle loro farmacopee e, questa, si è lentamente diffusa presso il mondo europeo invadendo i mercati del Mediterraneo. Nei testi medici e anche possibile trovare tentativi piu solidi di giustificare le proprieta terapeutiche delle mummie, attribuendole alle spezie con cui tali corpi antichi sono stati imbalsamati. Con Paracelso e il suo principio del “simile cura simile”, la mummia divenne in grado di curare il corpo umano in quanto, essa stessa, parte di un corpo umano. Keywords: Mummia, Medioevo, Medicina, Antropologia, Storia La mummia come farmaco Le antiche mummie egizie, per la loro innata incorruttibilità hanno sempre suscitato stupore ed emozione nell'animo umano. In particolare dal medioevo, questi corpi erano visti come dotati di capacità magiche ed erano utilizzati come talismani e medicinali. Non è ancora ben chiaro se l'idea della mummia come panacea universale sia nata dal fatto che i corpi imbalsamati erano in grado di conservarsi per millenni o dal momento che contenevano una moltitudine di sostanze medicinali quali pepe, natron, olio di cedro, mirra, cannella e balsami vari. Molto probabilmente entrambe queste idee, unite a una forte suscettibilità della popolazione, hanno permesso la diffusione di tale farmaco. -

Embodied Knowledge and Extra-Verbal Culture Short Table Of

Embodied Knowledge and Extra-Verbal Culture Version: 20191229 Author Information: Dr. Andreas Goppold The contact information is a graphic to keep away spammers. This file is located on the www server of the author: http://www.noologie.de/embodied.htm http://www.noologie.de/embodied.pdf Short Table of Contents 1 Local Hyperlinks.................................................................................................................9 2 Abbreviations and Terms...................................................................................................10 3 Abstract..............................................................................................................................12 4 The Hypertext and Multimedia Techniques used..............................................................13 5 Embodied vs. Objective Knowledge.................................................................................15 6 Current Approaches to Embodied Knowledge..................................................................25 7 Materials on Anthropological Theory................................................................................61 8 Language: A Subtle Ethnocentrism?................................................................................122 9 The Deep Structures of Mythology.................................................................................127 10 Notes on Various Dynamic Traditions...........................................................................149 11 Comments on Ethnological Theory -

Isabella Andorlini Isabella Πολλὰ Ἰατρῶν Πολλὰ Ἐστι Συγγράμματα Scritti Sui Papiri E La Medicina Antica Papiri E La Medicina Scritti Sui

Isabella Andorlini Isabella Andorlini Isabella Andorlini Isabella Andorlini πολλὰ ἰατρῶν ἐστι συγγράμματα (1955-2016), ricercatrice all’Istituto Il volume costituisce la raccolta Papirologico «Girolamo Vitelli» πολλὰ ἰατρῶν ἐστι συγγράμματα πολλὰ ἰατρῶν degli studi che Isabella Andorlini di Firenze per più di dieci anni, Scritti sui papiri e la medicina antica ha dedicato, nell’arco di più è stata chiamata nel 2005 di trent’anni di ricerca, all’Università di Parma come alle testimonianze papiracee Professore Associato di Papirologia. ἐστι συγγράμματα della medicina greco-romana Studiosa di riconosciuta fama in Egitto. Articoli ormai internazionale, specializzata πολλὰ ἰατρῶν ἐστι συγγράμματα. introvabili affiancano le ultime in particolare nello studio Scritti sui papiri e la medicina antica pubblicazioni, tracciando delle testimonianze papiracee variegati percorsi sulla medicina antica, ha pubblicato Che si tratti di prescrizioni e ricette di medicamenti vari, a cura di Nicola Reggiani multidisciplinari dedicati più di un centinaio di contributi manuali e trattati di medicina, o semplici lettere alla ricettazione medica antica, scientifici, e ha diretto un progetto alle testimonianze testuali e documenti scritti da antichi dottori, i papiri greci europeo di digitalizzazione dei papiri STUSMA – Studi sul Mondo Antico delle pratiche mediche e delle medici greci. Fra le numerose d’Egitto offrono un punto di vista privilegiato, malattie, ai supporti materiali curatele, si ricordano due volumi nella quotidianità della pratica d’uso, sull’arte medica del sapere medico antico, miscellanei di Greek Medical Papyri ellenistico-romana. Innumerevoli i percorsi d’indagine e di a progetti passati e presenti (Firenze 2001 e 2009) e importanti scoperta che si celano nei difficili frammenti di cui Isabella che idealmente connettono edizioni critiche (Trattato di medicina Andorlini rimane un’insuperata interprete e studiosa. -

Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy ~ a Suggestive Inquiry Into the Hermetic Mystery

Mary Anne Atwood Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy ~ A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery with a Dissertation on the more Celebrated of the Alchemical Philosophers Part I An Exoteric View of the Progress and Theory of Alchemy Chapter I ~ A Preliminary Account of the Hermetic Philosophy, with the more Salient Points of its Public History Chapter II ~ Of the Theory of Transmutation in General, and of the First Matter Chapter III ~ The Golden Treatise of Hermes Trismegistus Concerning the Physical Secret of the Philosophers’ Stone, in Seven Sections Part II A More Esoteric Consideration of the Hermetic Art and its Mysteries Chapter I ~ Of the True Subject of the Hermetic Art and its Concealed Root. Chapter II ~ Of the Mysteries Chapter III ~ The Mysteries Continued Chapter IV ~ The Mysteries Concluded Part III Concerning the Laws and Vital Conditions of the Hermetic Experiment Chapter I ~ Of the Experimental Method and Fermentations of the Philosophic Subject According to the Paracelsian Alchemists and Some Others Chapter II ~ A Further Analysis of the Initial Principle and Its Education into Light Chapter III ~ Of the Manifestations of the Philosophic Matter Chapter IV ~ Of the Mental Requisites and Impediments Incidental to Individuals, Either as Masters or Students, in the Hermetic Art Part IV The Hermetic Practice Chapter I ~ Of the Vital Purification, Commonly Called the Gross Work Chapter II ~ Of the Philosophic or Subtle Work Chapter III ~ The Six Keys of Eudoxus Chapter IV ~ The Conclusion Appendix Part I An Exoteric View of the Progress and Theory of Alchemy Chapter I A Preliminary Account of the Hermetic Philosophy, with the more Salient Points of its Public History The Hermetic tradition opens early with the morning dawn in the eastern world. -

HISTORY of ALCHEMY Textbook: Linden, Stanton J. 2003. The

Angela Catalina Ghionea Office Hours: W 3:30 – 5:20 pm, UNIV 008 [email protected] and by appointment HISTORY OF ALCHEMY HIST 302 - Fall 2011 MWF 2:30 – 3:20, UNIV 219 I. ASSIGNED READINGS You are required to purchase a textbook and an i>clicker remote for in-class participation. Both the textbook and the i>Clicker remote are available for purchase/rent at any Purdue University Bookstore. Textbook: Linden, Stanton J. 2003. The alchemy reader: from Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton. New York: Cambridge University Press. One copy for the textbook has also been placed on reserve at Hicks Undergraduate Library, and available only at the library (ask Circulation Services at the front desk). Texts are assigned daily to be discussed in class: some available in the textbook, some to be found in pdf. format, posted on the Blackboard LEARN (the online course website). The texts (primary and secondary sources) must be brought in the class. Discussions of these texts count for participation (see the class schedule below). II. OBJECTIVES: The course investigates the history of alchemy and specific non-rational methods employed by many scientists to promote rational discoveries. The course is mainly focused on European alchemy, with few references to Middle Eastern and Arabic alchemy. It spans the period from Antiquity to Renaissance and Early Modern period, and also touches upon nineteenth-century “occult fever” and obsession with alchemy. The course is interdisciplinary and investigates both history of alchemy as well as the more general history -

Paula Alexandra Da Silva Veiga Introdution

HEALTH AND MEDICINE IN ANCIENT EGYPT : MAGIC AND SCIENCE 3.1. Origin of the word and analysis formula; «mummy powder» as medicine………………………..52 3.2. Ancient Egyptian words related to mummification…………………………………………55 3.3. Process of mummification summarily HEALTH AND MEDICINE IN ANCIENT EGYPT : MAGIC AND described……………………………………………….56 SCIENCE 3.4. Example cases of analyzed Egyptian mummies …………………............................................61 Paula Alexandra da Silva Veiga 2.Chapter: Heka – «the art of the magical written word»…………………………………………..72 Introdution…………………………………………......10 2.1. The performance: priests, exorcists, doctors- 1.State of the art…..…………………………………...12 magicians………………………………………………79 2.The investigation of pathology patterns through 2.2. Written magic……………………………100 mummified human remains and art depictions from 2.3. Amulets…………………………………..106 ancient Egypt…………………………………………..19 2.4. Human substances used as ingredients…115 3.Specific existing bibliography – some important examples……………..………………………………...24 3.Chapter: Pathologies’ types………………………..118 1. Chapter: Sources of Information; Medical and Magical 3.1. Parasitical..………………………………118 Papyri…………………………………………………..31 3.1.1. Plagues/Infestations…..……….……....121 3.2. Dermatological.………………………….124 1.1. Kahun UC 32057…………………………..33 3.3. Diabetes…………………………………126 1.2. Edwin Smith ………………..........................34 3.4. Tuberculosis 1.3. Ebers ……………………………………….35 3.5. Leprosy 1.4. Hearst ………………………………………37 ……………………………………128 1.5. London Papyrus BM 10059……..................38 3.6. Achondroplasia (Dwarfism) ……………130 1.6. Berlin 13602; Berlin 3027; Berlin 3.7 Vascular diseases... ……………………...131 3038……………………………………………………38 3.8. Oftalmological ………………………….132 1.7. Chester Beatty ……………………………...39 3.9. Trauma ………………………………….133 1.8. Carlsberg VIII……………..........................40 3.10. Oncological ……………………………136 1.9. Brooklyn 47218-2, 47218.138, 47218.48 e 3.11. Dentists, teeth and dentistry ………......139 47218.85……………………………………………….40 3.12. -

Lavinia Fontana's Cleopatra the Alchemist

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, August 2018, Vol. 8, No. 8, 1159-1180 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.08.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING Lavinia Fontana’s Cleopatra the Alchemist Liana de Girolami Cheney SIELE, Universidad de Coruña, Spain The purpose of this essay is to identify and analyze one of Lavinia Fontana’s mysterious paintings, traditionally entitled Cleopatra but here considered to be an inventive portrayal of an ancient scientist, Cleopatra the Alchemist (ca. third century BCE). There are four parts to this study. The first is an iconographical analysis of the painting by Lavinia Fontana’s Cleopatra the Alchemist (1605) at the Galleria Spada in Rome. The second section deals with the origin of the Egyptian Cleopatra the Alchemist as an Egyptian scientist and of her inventions, which include the alembic and the ouroboros motif. The third section consists of an emblematic comparison between the imagery in the painting and alchemical references. The last brief section considers problematic copies of the painting. Keywords: alchemy, art, symbolism, serpent, ouroboros, famous women, alembic, Lavinia Fontana, Egyptian mythology, Plato’s Timaeus, artistic forgery Introduction The representation of famous personages in the history of art is further expanded in the Italian sixteenth century. Artists and humanists continued with the classical and Renaissance traditions of immortalizing uomini famosi and donne famose (famous men and famous women).1 The Italian painter from Bologna, Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), during the sixteenth century followed this convention of representing donne famose in 2 her depiction of Cleopatra the Alchemist of 1605-1614 at the Galleria Spada in Rome (Figure 1). -

Wooden Coffin of Djedmut, in the Collection of the Vatican's Muse

Opposite & detail this page, the Late Period polychrome- wooden coffin of Djedmut, in the collection of the Vatican’s Museo Gregorian Egizio (Inv. 25008) . Kmt 30 SCIENTIFIC MUMMY STUDIES AT THE VATICAN by Lucy Gordan-Rastelli Photos courtesy the Vatican Museums he first modern scientific examinations of mum - mies were conducted in 1901 by professors at T the English-language Government School of Medicine in Cairo. Two years later Professor Grafton Elliot Smith, an Australian and proponent of the hyper-diffusion - ist view of history, and British Egyptologist Howard Carter took the first x-ray of a mummy. They used the only radi - ography machine in Cairo to examine the well-preserved remains of Thutmose IV, discovered in the Second Royal Mummies Cache, KV35, in 1898. Around the same time, British chemist Alfred Lucas applied analyses to mummies and learned a great deal about the substances used by the ancient Egyptians in embalming. Later, in 1922, Lucas studied the recently discovered mummy of Tutankhamen. As for pathology, in 1992, at the first World Congress on Mummy Studies, held at Puerto de la Cruz on Tenerife in the Canary Islands, more than 300 scientists shared and integrated nearly 100 years of collected biomedical and bioarcheological data. Most recently CT-scanning has al - lowed scientists to digitally “unwrap” mummies without risking damage to either their bandaging or bodies. 31 Kmt Above, One of the Vatican’s two false mummies being CT-scanned. Below, CT views of false mummies 57852 & 57853. Two views of the Vatcan’s false mummy, Inv. 57853 In 2006, shortly after the publication of my “Ancient Egypt - contents inside.” Most of these exams have been carried out at ian and Egyptianized Roman Art in Vatican City,” Dr. -

1 00 Books on Alchemy to Find on a Bookshelf 1

1 00 Books on Alchemy to Find on a Bookshelf 1. Baopuzi by Ge Hong 1144 by Robert of Chester to, late 13th century, (Written in the 4th3rd as The Book of the originally Latin, On the Use century BC, originally Composition of Alchemy, of Fire to Conflagrate the Chinese, Book of the Master how Morienus in the 7th Enemy, or Book of Fires for Who Embraces Simplicity, century learned the secrets the Burning of Enemies, 35 Chinese alchemy, elixirs, of alchemy and introduced it recipes for incendiary demonology and into Islam, reveals the weapons, fire and immortality) secrets of the work of gunpowder) 2. Zhouyi cantong qi by Wei alchemy) 12. Cyranides (Compiled in Boyang (Written in the mid 7. Turba Philosophorum 14th century, Greek, second century, Chinese, (Latin, Assembly of the magicomedical works, The Kinship of the Three, in Philosophers, circa 900, magical properties of plants, Accordance with the Book of based on Arabic texts, a animals and gemstones, an Changes, English translation discussion between nine encyclopaedia of amulets 1932, cosmology, Taoism Greek philosophers who and the history of western and alchemy, especially adapt Greek alchemy into alchemy) internal alchemy) Islamic science) 13. Aurora Consurgens by 3. Chrysopeoeia of Cleopatra 8. Liber de compositione Thomas Aquinas (Attributed by Cleopatra the Alchemist alchimiae by Robert of to, author now unknown, (Written in 3rd century Chester (1144, Latin, The 15th century, Latin, an Egypt, the original is an Combination of Alchemy, the illustrated commentary on illustrated single sheet of first European book on the Latin translation of papyrus on goldmaking) alchemy, translated from the Silvery Waters by Senior 4. -

Comercio Y Cultura En La Edad Moderna

Juan José Iglesias Rodríguez Rafael M. Pérez García Manuel F. Fernández Chaves (eds.) COMERCIO Y CULTURA EN LA EDAD MODERNA Contiene los textos de las comunicaciones de la XIII Reunión Científica de la Fundación Española de Historia Moderna EDITORIAL UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA COMERCIO Y CULTURA EN LA EDAD MODERNA Juan José Iglesias Rodríguez Rafael M. Pérez GarcÍa Manuel F. Fernández Chaves (eds.) COMERCIO Y CULTURA EN LA EDAD MODERNA COMUNICACIONES DE LA XIII REUNIÓN CIENTÍFICA DE LA FUNDACIÓN ESPANOLA DE HISTORIA MODERNA ~~SIO"'C Íl~)eus Editorial Universidad de Sevilla Sevilla 2015 Serie: Historia y Geografia NÚlll.: 291 COMrrÉ EDITORIAL: Antonio Caballos Rufino (Director de la Editorial Universidad de Sevilla) Eduardo FerreJ" Albelda (Subdirector) Mannel Espejo y Lerdo de Tejada Jnan José Iglesias Rodríguez Jnan Jim.énez-Castellanos Ballesteros Isabel López Calderón Jnan Montero Delgado Lourdes Mlmduate Jaca Jaime Navarro Casas M'- del Pópulo Pablo-Romero Gil-Delgado Adoracióu Rueda Rueda Rosario Villegas Sánchez Reservados todos los derechos. Ni la totalidad ni parte de este libro pue de reprodllCirse o transmitirse por ningún procedimiento electrónico o mecánico, incluyendo fotocopia, grabación magnética o cualquier alma cenamiento de infonnación y sistema de recuperación, sin penniso escrito de la Editorial Universidad de Sevilla. Obra editada en colaboración con la Fundación Espal.iola de Historia Modema Motivo de cubierta: Vista de Sevilla el! el siglo xn, por A. Sánchez Coello o Editorial Universidad de Sevilla 2015 CI POIVenir. 27 - 41013 Sevilla. Tlfs.: 954 487 447; 954 487 451; Fax: 954 487 443 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Web: <hllp://www.editoria1.us.es> o POR LOS TEXTOS, SUS AUTORES 2015 O JUAN JOSÉ IGLESIAS RODRÍGUEZ, RAFAEL M. -

Marketing Nature: Apothecaries, Medicinal Retailing, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Venice, 1565-1730

Marketing Nature: Apothecaries, Medicinal Retailing, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Venice, 1565-1730 by Sean David Parrish Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John Jeffries Martin, Supervisor ___________________________ Thomas Robisheaux ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Valeria Finucci Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT Marketing Nature: Apothecaries, Medicinal Retailing and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Venice, 1565-1730 by Sean David Parrish Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John Jeffries Martin, Supervisor ___________________________ Thomas Robisheaux ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Valeria Finucci An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Sean David Parrish 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the contributions of apothecary craftsmen and their medicinal retailing practices to emerging cultures of scientific investigation and experimental practice in the Italian port city of Venice between 1565 and 1730. During this important period in Europe’s history, efforts to ground traditional philosophical