Lavinia Fontana's Mythological Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Framing the Painting: the Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[S]: Leonée Ormond Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5300/framing-the-painting-the-victorian-picture-sonnet-author-s-leon%C3%A9e-ormond-source-moveabletype-vol-5300.webp)

Framing the Painting: the Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[S]: Leonée Ormond Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Framing the Painting: The Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[s]: Leonée Ormond Source: MoveableType, Vol. 2, ‘The Mind’s Eye’ (2006) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.012 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2006 Leonée Ormond. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Framing the Painting: The Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Leonée Ormond During the Victorian period, the short poem which celebrates a single work of art became increasingly popular. Many, but not all, were sonnets, poems whose rectangular shape bears a satisfying similarity to that of a picture frame. The Italian or Petrarchan (rather than the Shakespearean) sonnet was the chosen form and many of the poems make dramatic use of the turn between the octet and sestet. I have chosen to restrict myself to sonnets or short poems which treat old master paintings, although there are numerous examples referring to contemporary art works. Some of these short “painter poems” are largely descriptive, evoking colour, design and structure through language. Others attempt to capture a more emotional or philosophical effect, concentrating on the response of the looker-on, usually the poet him or herself, or describing the emotion or inspiration of the painter or sculptor. Some of the most famous nineteenth century poems on the world of art, like Browning’s “Fra Lippo Lippi” or “Andrea del Sarto,” run to greater length. -

Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) and the Burlesque

Antonfrancesco Grazzini ‘Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) and the Burlesque Poetry, Performance and Academic Practice in Sixteenth‐Century Florence Antonfrancesco Grazzini ‘Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) en het burleske genre Poëzie, opvoeringen en de academische praktijk in zestiende‐eeuws Florence (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. J.C. Stoof, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 9 juni 2009 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Inge Marjo Werner geboren op 24 oktober 1973 te Utrecht Promotoren: Prof.dr. H.A. Hendrix Prof.dr. H.Th. van Veen Contents List of Abbreviations..........................................................................................................3 Introduction.........................................................................................................................5 Part 1: Academic Practice and Poetry Chapter 1: Practice and Performance. Lasca’s Umidian Poetics (1540‐1541) ................................25 Interlude: Florence’s Informal Literary Circles of the 1540s...........................................................65 Chapter 2: Cantando al paragone. Alfonso de’ Pazzi and Academic Debate (1541‐1547) ..............79 Part 2: Social Poetry Chapter 3: La Guerra de’ Mostri. Reviving the Spirit of the Umidi (1547).......................................119 Chapter 4: Towards Academic Reintegration. Pastoral Friendships in the Villa -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 10:23:11PM Via Free Access Notes to Chapter 1 671

Notes 1 Introduction. Fall and Redemption: The Divine Artist 1 Émile Verhaeren, “La place de James Ensor Michelangelo, 3: 1386–98; Summers, Michelangelo dans l’art contemporain,” in Verhaeren, James and the Language of Art, 238–39. Ensor, 98: “À toutes les périodes de l’histoire, 11 Sulzberger, “Les modèles italiens,” 257–64. ces influences de peuple à peuple et d’école à 12 Siena, Church of the Carmines, oil on panel, école se sont produites. Jadis l’Italie dominait 348 × 225 cm; Sanminiatelli, Domenico profondément les Floris, les Vaenius et les de Vos. Beccafumi, 101–02, no. 43. Tous pourtant ont trouvé place chez nous, dans 13 E.g., Bhabha, Location of Culture; Burke, Cultural notre école septentrionale. Plus tard, Pierre- Hybridity; Burke, Hybrid Renaissance; Canclini, Paul Rubens s’en fut à son tour là-bas; il revint Hybrid Cultures; Spivak, An Aesthetic Education. italianisé, mais ce fut pour renouveler tout l’art See also the overview of Mabardi, “Encounters of flamand.” a Heterogeneous Kind,” 1–20. 2 For an overview of scholarship on the painting, 14 Kim, The Traveling Artist, 48, 133–35; Payne, see the entry by Carl Van de Velde in Fabri and “Mescolare,” 273–94. Van Hout, From Quinten Metsys, 99–104, no. 3. 15 In fact, Vasari also uses the term pejoratively to The church received cathedral status in 1559, as refer to German art (opera tedesca) and to “bar- discussed in Chapter Nine. barous” art that appears to be a bad assemblage 3 Silver, The Paintings of Quinten Massys, 204–05, of components; see Payne, “Mescolare,” 290–91. -

Marzo - Aprile 2021 PROGRAMMA DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI Marzo - Aprile 2021 RIEPILOGO DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI

marzo - aprile 2021 PROGRAMMA DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI marzo - aprile 2021 RIEPILOGO DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI CONFERENZE - PRESENTAZIONI 2 marzo Artisti/collezionisti tra Cinquecento e Settecento 9 marzo Le donne nell’architettura tra XX e XXI secolo 16 marzo Dante fra arte e poesia 23 marzo La rivincita delle artiste nella pittura del ‘600 - parte II 30 marzo Il “mio”Arturo 6 aprile Arte al tempo di Dante: “Ora ha Giotto il grido!” 20 aprile La lettera di Raffaello a Leone X: nasce la moderna concezione di conservazione dei beni culturali PALAZZI, MUSEI E SITI ARTISTICO/ARCHITETTONICI 11 marzo Il Cimitero Monumentale VISITE A CHIESE 4 marzo Santa Maria Beltrade: Deco’, ma non si direbbe 15 marzo San Marco 24 marzo Chiesa e museo di San Fedele 26 aprile San Francesco al Fopponino VISITE A MOSTRE 10 marzo “Tiepolo. Venezia, Milano, l’Europa” alle Gallerie d’Italia 31 marzo Carla Accardi, una donna come tante, al Museo del ‘900 7 aprile Robot al Mudec: scienza, tecnica, arte, antropologia 14 aprile “Tiepolo. Venezia, Milano, l’Europa” alle Gallerie d’Italia 16 aprile Le Signore del Barocco a Palazzo Reale in copertina: Domenico di Michelino, affresco, 1465, cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore - Firenze 2 ITINERARI D’ARTE 18 marzo Dal teatro Dal Verme alla chiesa di Santa Maria alla Porta 22 marzo Una passeggiata lungo le mura spagnole 29 marzo I segreti della Via Moscova e dintorni 12 aprile Nuovi Arrivi tra Piazza Liberty/Piazza Cordusio/via Brisa: la città che cambia 13 aprile Dal Carrobbio alla Darsena, le porte “Ticinesi” e la Milano nei secoli 22 aprile Da piazza della Scala a piazza Belgioioso 27 aprile La lunga storia del Portello ed il nuovo parco Programma elaborato dal team degli Storici dell’Associazione, coordinati dal dott. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Lund Humphries and Getty Publications to collaborate on a groundbreaking new book series highlighting the careers and achievements of women artists LONDON AND LOS ANGELES—Lund Humphries and Getty Publications are pleased to announce the joint publication of the first volumes in the Illuminating Women Artists series. This series of beautifully illustrated books is the first to focus in a deliberate and sustained way on women artists throughout history, to recognize their accomplishments, to revive their name recognition, and to make their works better known to art enthusiasts of the 21st century. The Illuminating Women Artists series launches at a critical moment in our culture. It is a significant contribution to a movement underway—among scholars, museums, art dealers and collectors, and the wider world of cultural heritage—to re-assess the contributions of women artists. The first sub- series focuses on artists from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The initial volume in the series, by Catherine Hall-van den Elsen, presents the first overview in English of the life and work of Luisa Roldán (1652–1706), a prolific and celebrated sculptor of the Spanish Golden Age. The book, due for publication in September 2021, is replete with invaluable insights into Roldán’s technical innovations and artistic achievements, and it includes a list of all known extant works by the artist. It will be followed in February 2022 by a volume featuring the Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1654), who was recently celebrated in a solo exhibition at London’s National Gallery. Through the lens of cutting-edge scholarship, recent archival discoveries, and new painting attributions, author Sheila Barker offers an engaging overview of Gentileschi’s dramatic and exceptional life story, as well as her enterprising and original engagement with emerging feminist notions of the value and dignity of womanhood. -

BM Tour to View

08/06/2020 Gods and Heroes The influence of the Classical World on Art in the C17th and C18th The Tour of the British Museum Room 2a the Waddesdon Bequest from Baron Ferdinand Rothschild 1898 Hercules and Achelous c 1650-1675 Austrian 1 2 Limoges enamel tazza with Judith and Holofernes in the bowl, Joseph and Potiphar’s wife on the foot and the Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite/Venus on the stem (see next slide) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600-1630 Omphale by Artus Quellinus the Elder 1640-1668 Flanders 3 4 see previous slide Limoges enamel salt-cellar of piédouche type with Diana in the bowl and a Muse (with triangle), Mercury, Diana (with moon), Mars, Juno (with peacock) and Venus (with flaming heart) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600- 1630 (also see next slide) 5 6 1 08/06/2020 Nautilus shell cup mounted with silver with Neptune on horseback on top 1600-1650 probably made in the Netherlands 7 8 Neptune supporting a Nautilus cup dated 1741 Dresden Opal glass beaker representing the Triumph of Neptune c 1680 Bohemia 9 10 Room 2 Marble figure of a girl possibly a nymph of Artemis restored by Angellini as knucklebone player from the Garden of Sallust Rome C1st-2nd AD discovered 1764 and acquired by Charles Townley on his first Grand Tour in 1768. Townley’s collection came to the museum on his death in 1805 11 12 2 08/06/2020 Charles Townley with his collection which he opened to discerning friends and the public, in a painting by Johann Zoffany of 1782. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Francesco Cavazzoni Pittore E Scrittore

IGURE F 3 - 2017 Francesco Cavazzoni pittore e scrittore Negli anni successivi al Concilio di Trento si assiste nei territori Lo utilizza soprattutto, e con continuità, Prospero Fontana. La dello Stato Pontifi cio e in quelli rimasti cattolici all’elaborazione propensione descrittiva nei suoi quadri è la stessa, simili sono la di un nuovo tipo di pala d’altare. Il modo diverso di intendere la gestualità dei protagonisti e l’intensità espressiva, simile la mate- devozione sollecita nuove forme artistiche e una nuova strategia ria pittorica, simile lo spirito con cui il pittore aderisce ai passi di comunicazione. Le ripercussioni nella cultura fi gurativa sono evangelici. notevoli fi no agli anni venti del Seicento e oltre. A Bologna i Scarse le informazioni biografi che nonostante alcune signifi cative Paleotti, Gabriele (al governo della metropolitana dal 1565 al commissioni per collocazioni sia pubbliche sia private, tuttora non 1591) prima, il cugino Alfonso, suo coadiutore indi successore conosciamo neppure le date di nascita e di morte. Pittore e scrittore (1591-1610), hanno lasciato segni non meno importanti sia nella devoto in stretto e ripetuto collegamento con la famiglia Pepoli, lo pratica liturgica, sia nell’equilibrio dei poteri fra le istituzioni sappiamo attivo nelle botteghe di Bartolomeo Passerotti e di Ora- civili e religiose e la sede pontifi cia romana, sia nel coinvolgimento zio Samachini, sensibile alla maniera di entrambi. Dopo lavori delle arti. Li guida la convinzione che alla sollecitazione dei a Pesaro e a Città di Castello, è impegnato a Bologna soprat- sensi, la vista soprattutto e l’udito per il canto e la musica, fos- tutto nell’ultimo ventennio del Cinquecento. -

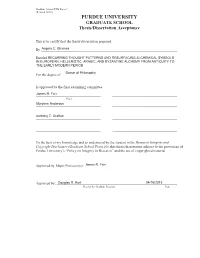

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Following the Early Modern Engraver, 1480-1650 September 18, 2009-January 3, 2010

The Brilliant Line: Following the Early Modern Engraver, 1480-1650 September 18, 2009-January 3, 2010 When the first engravings appeared in southern Germany around 1430, the incision of metal was still the domain of goldsmiths and other metalworkers who used burins and punches to incise armor, liturgical objects, and jewelry with designs. As paper became widely available in Europe, some of these craftsmen recorded their designs by printing them with ink onto paper. Thus the art of engraving was born. An engraver drives a burin, a metal tool with a lozenge-shaped tip, into a prepared copperplate, creating recessed grooves that will capture ink. After the plate is inked and its flat surfaces wiped clean, the copperplate is forced through a press against dampened paper. The ink, pulled from inside the lines, transfers onto the paper, printing the incised image in reverse. Engraving has a wholly linear visual language. Its lines are distinguished by their precision, clarity, and completeness, qualities which, when printed, result in vigorous and distinctly brilliant patterns of marks. Because lines once incised are very difficult to remove, engraving promotes both a systematic approach to the copperplate and the repetition of proven formulas for creating tone, volume, texture, and light. The history of the medium is therefore defined by the rapid development of a shared technical knowledge passed among artists dispersed across Renaissance and Baroque (Early Modern) Europe—from the Rhine region of Germany to Florence, Nuremberg, Venice, Rome, Antwerp, and Paris. While engravers relied on systems of line passed down through generations, their craft was not mechanical. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Pitman, Sophie; Smith, Pamela ; Uchacz, Tianna; Taape, Tillmann; Debuiche, Colin the Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, Spectacle, and Power in Early Modern Europe

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Pitman, Sophie; Smith, Pamela ; Uchacz, Tianna; Taape, Tillmann; Debuiche, Colin The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, spectacle, and power in early modern Europe Published in: RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY DOI: 10.1017/rqx.2019.496 Published: 01/01/2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please cite the original version: Pitman, S., Smith, P., Uchacz, T., Taape, T., & Debuiche, C. (2020). The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, spectacle, and power in early modern Europe. RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY, 73(1), 78-131. [0034433819004962]. https://doi.org/10.1017/rqx.2019.496 This material is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, Spectacle, and Power in Early Modern Europe PAMELA H. SMITH, Columbia University TIANNA HELENA UCHACZ, Columbia University SOPHIE PITMAN, Aalto University TILLMANN TAAPE, Columbia University COLIN DEBUICHE, University of Rennes Through a close reading and reconstruction of technical recipes for ephemeral artworks in a manu- script compiled in Toulouse ca. 1580 (BnF MS Fr. 640), we question whether ephemeral art should be treated as a distinct category of art.