Accounting Information for Management Decision-Making--A Case Study in the Household Goods Moving and Storage Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moveware (27) Senate Forwarding Inc

www.iamovers.org VOLUME XLIX The Journal of the International Association of Movers July / August 2017 Canada!Salute to AD_The Portal_GM-DTmoving-Packimpex_216x280.indd 1 27/06/2017 15:56 AD_The Portal_GM-DTmoving-Packimpex_216x280.indd 1 27/06/2017 15:56 ONE SYSTEM FOR ALL YOUR MOVE MANAGEMENT NEEDS Your EDC-MoveStar® Town Experience: 1 - Software tailored to your business. 2 - The GOgistiX® network at your fingertips. 3 - Exceptional customer service. 4 - One all-inclusive price. 5 - Every user has a voice in shaping the software. Innovation that keeps you moving. 2016–2017 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE CONTENTS PRESIDENT Terry R. Head THE PORTAL • May/June 2017 • Volume XLVIX CHAIR Margaret (Peg) Wilken 6 HEADLINES / Terry R. Head Stevens Forwarders Inc. From Sea to Sea VICE CHAIR Tim Helenthal FEATURES National Van Lines, Inc. GOVERNING MEMBERS AT LARGE 9 PORTAL FOCUS: A SALUTE TO CANADA Georgia Angell O, Canada: A Vast and Diverse Landscape for Movers / Joyce Dexter Foremost Forwarders, Inc. Contributors featured: John Burrows Tippet Richardson (9) • AMJ Campbell International (10) • MoverOne International (13) • DeWitt Moving & Storage King’s Global Forwarding Limited (16) • Orbit International Moving Logistics Ltd. (16) • Stephan Geurts Jr. World Wide Overseas Moving Service Inc. (18) • Quality Move Management (19) • GovLog, N.V. Matco Moving Solutions (21) • T-R Westcan, Inc. (24) • Armstrong International Movers (25) Michael Richardson • Voxme Software (26) • Moveware (27) Senate Forwarding Inc. CORE MEMBERS REPRESENTATIVE 28 CAM: Strengthening Industry Standards and Professional Bonds in Canada / Boris Populoh Will Kohudic Willis Relocation Risk Group 33 IAM Young Professionals (IAM-YP) CORE MEMBERS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE 33 Young Movers Conference Recap / Margaret Kerr Tony Waugh AGS France 34 Organizing the YMC: Challenging, Fun .. -

NSIAD-90-50 Household Goods: Competition Among Commercial

4 United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Legislation GAO and National Security Subcommittee, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives HOUSEHOLD GOODS Competition Among Commercial Movers Serving DOD Can Be Improved National Security and International Affairs Division B-23767 1 February 12,199O The Honorable John Conyers, Jr. Chairman, Legislation and National Security Subcommittee Dear Mr, chairman: This report responds to a request by the former Subcommittee Chairman that we review the practices and procedures of the Department of Defense in procuring commercial household goods shipping services for personnel being transferred at government expense between duty stations within the United States. Unless you publicly announce its contents earlier, we plan no further distribution of this report for 30 days. At that time, we will send copies to the Secretaries of Defense, the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force; the Chairmen, House and Senate Committees on Armed Services and on Appropriations; the Director, Office of Management and Budget; and to other interested parties. This report was prepared under the direction of Richard Davis, Director, Army Issues, who may be reached at (202) 275-4141 if you or your staff have any questions. GAOstaff members who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV. Sincerely yours, Frank C. Conahan Assistant Comptroller General ljxecutive Summary The Department of Defense spends over $400 million dollars a year to Purpose ship and store the household goods of its members authorized to make a transfer or to relocate within the 48 contiguous United States. The money is paid to commercial household goods carriers and their agents located throughout the United States. -

The Defense Transportation and Logistics Community Will Be There

The Defense Transportation and Logistics Community Will Be There MAXIMIZE YOUR VISIBILITY. NETWORK WITH KEY DECISION MAKERS. ENHANCE YOUR VALUE. BUILD STRATEGIC RELATIONSHIPS Sponsor and Exhibit at the 2019 NDTA Fall Exposition Make plans to join us in St. Louis, MO October 7-10 for the 2019 NDTA Fall Exposition. This is the only venue focused directly on networking with top level government and industry decision makers in transportation, logistics, distribution, passenger services, and related industries. Develop and Strengthen Your Brand Establish industry positioning. Demonstrate your latest equipment, products and services. Gain a Competitive Edge Participation as a sponsor and exhibitor illustrates your company’s prod- ucts and services are aligned with the vision and objectives of NDTA and its members. Interact with Decision Makers and Key Influencers With more than 1,300 projected attendees from the military and govern- ment as well as industry, the NDTA Fall Exposition provides opportunities to develop new business leads while enhancing existing relationships, enabling you to provide the ideas and solutions needed to address ongo- ing challenges to our nation’s defense. Build and strengthen relationships with top and mid-level managers in industry and military and government. Interact with your military and government customers, including the com- manders and leaders of those organizations. Troubleshoot with other key players. The NDTA Fall Exposition provides a cost-effective way to meet face-to- face with the influencers and decision makers who are critical to meeting your goals, while at the same time reinforcing your company image with representatives from a wide array of industries, including: airlines, rail- roads, motor carriers, ocean shippers, transportation consultants, cyber security, security, travel and hospitality, express companies, technology, household goods carriers, labor unions, port authorities, and 3PLs. -

Domestic Customer Service Index Scores Effective November 1, 2010

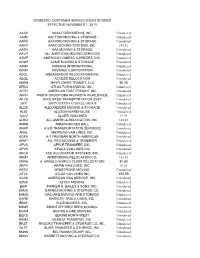

DOMESTIC CUSTOMER SERVICE INDEX SCORES EFFECTIVE NOVEMBER 1, 2010 AAAA AAAA FORWARDING, INC. Unindexed AAIM AACTION MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed AAPG AAA PRO MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. 101.82 AASH AAA MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed AAVH ALL AMERICAN MOVING SERVICES Unindexed AAVP AMERICAN VANPAC CARRIERS, INC. Unindexed ACMH ACME MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed ADIM ADRIANA INTERNATIONAL Unindexed ADMV ADVANCE CORPORATION Unindexed ADOL AMBASSADOR RELOCATIONS INC Unindexed AEQL ACCESS RELOCATION Unindexed AERM MAYFLOWER TRANSIT, LLC 94.30 AFDG ATLAS FORWARDING, INC. Unindexed AFFH AMERICAN FAST FREIGHT INC Unindexed AFIW PASHA GROUP DBA AFI/PASHA WORLDWIDE Unindexed AFTS AFFILIATED TRANSPORTATION SYST Unindexed AIGP ARPIN INTERNATIONAL GROUP Unindexed ALDS ALEXANDERS MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed ALIS ALLISON WAREHOUSE Unindexed ALLV ALLIED VAN LINES 97.93 ALRQ ALL AMERICA RELOCATION, INC. 102.43 AMRB AMERICAN RED BALL Unindexed ANBP A & B TRANSPORTATION SERVICES Unindexed ANVL ANDREWS VAN LINES, INC. Unindexed AOFA A-1 FREEMAN NORTH AMERICAN Unindexed APMT ALL PRO MOVING & TRANSFER Unindexed APVA APPLE TRANSFER, INC. Unindexed APVN APACA VAN LINES INC Unindexed ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. Unindexed ARMT ARMSTRONG RELOCATION CO. 101.55 ARNA A. ARNOLD WORLD CLASS RELOCATION 91.80 ARPV ARPIN VAN LINES, INC. 96.67 ARSG ARMSTRONG MOVING Unindexed ATVL ATLAS VAN LINES INC 100.59 AVAS AMERICAN VAN SERVICE, INC. Unindexed AZMC AZTEC MOVING Unindexed BAIP PARKER K. BAILEY & SONS, INC. Unindexed BAMO BARNES MOVING & STORAGE CO. Unindexed BAMQ BALLARD MOVING AND STORAGE Unindexed BARK BARKLEY TRUCK LINES, INC. Unindexed BBAF B & B MOVERS, INC. Unindexed BBMS BRANTLEY BROTHERS MOVING Unindexed BEKM BEKINS A-ONE MOVERS Unindexed BEKS BEKINS NORTHWEST Unindexed BEMJ BEMIDJI TRANSFER, INC. -

Secretary of State Division of Business Services Foreign Charters 1874-1971 Record Group

SECRETARY OF STATE DIVISION OF BUSINESS SERVICES FOREIGN CHARTERS 1874-1971 RECORD GROUP 281 Processed by: Ted Guillaum Archives Technical Services Tennessee State Library & Archives Date Completed: 5-24-2001 MICROFILM ONLY INTRODUCTION Record Group 281, Secretary of State, Division of Business Services, Foreign Charters, 1874-1971, contains 180 cubic feet of documents filed by corporations from out of state doing business in Tennessee. These forms were filed with the Secretary of State and are arranged numerically, however, there is also an alphabetical index. Under Tennessee statute it is the ministerial duty for The Secretary of State to file corporate documents and to maintain a record of the filings. Every foreign (non- Tennessee) corporation that intends to conduct business in Tennessee must first register their corporation with the Secretary of State. To register the foreign corporation in Tennessee, the corporation would file a copy of its charter. A charter is the legal document that establishes the corporation as a legal entity. The registration includes a principal address for the corporation and a registered agent address for service of process. This record group was microfilmed and the originals disposed of according to the Tennessee State RDA for these records. SCOPE AND CONTENT Record Group 281, Secretary of State, Division of Business Services, Foreign Charters, contains 180 cubic feet of documents spanning the years 1874 through 1971. The record group consists of reports filed by corporations headquarted outside of Tennessee. The Division of Business Services originally maintained these records in numerical order but the numerical index evidently was abandoned at some point. -

Highlights of This Issue

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 1973 WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 38 ■ Number 25 Pages 3497-3570 PART I (Part II begins on page 3565) HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS ISSUE This listing does not affect the legal status of any document published in this issue. Detailed table of contents appears inside. REMINDERS— Next week's deadlines for comments on proposed rules; next week’s hearings and rules going into effect today................................ ................................................... 3498 AMERICAN HEART M ONTH, 1973— Presidential procla mation ..............................................................„ ........... ............... 3503 COSMETICS— FDA proposes format for mandatory cos metic ingredient labeling; comments by 4 -9 -7 3 .................. 3523 ANTIBIOTICS, NEW DRUGS, AND NEW ANIMAL DRUGS— Gestest Tablets: FDA, citing potential dangers, proposes to withdraw approval and gives notice of opportunity fori hearing.................................................................................. 3534 Tylandril Tablets: FDA withdraws approval for lack of effectiveness.................-............................................................ 3534 Nitrophenide: FDA prohibits use in animal feeds; effec tive 3 -2 1 -7 3 ............................................................................ 3507 Megasul Premix 25% : FDA withdraws approval of this nitrophenide compound........................................... 3535 FOREIGN AID— AID regulations limiting employment of third country nationals on construction projects in recipient countries; -

Pulling Back the Curtain on Risk Management and Claims

www.iamovers.org VOLUME XLVII The Journal of the International Association of Movers May / June 2015 Pulling Back the Curtain on Risk Management and Claims get in touch Adv_Goss_Portal_21,6x28.indd 1 23/10/14 13:36 www.compactmovers.com Risk management solutions for the transportation and moving industry Wells Fargo Insurance understands that the handling of household goods damage requires a sensitive approach compared with usual marine cargo claims. Through offices located in Singapore, London, New York, and Los Angeles, our network of dedicated survey agents and repair firms can help you manage settlements almost anywhere in the world. • Online administrative tools • Errors and omissions • Open marine cargo/shipper’s interest • Directors’ and officers’ • Motor truck cargo • Commercial auto • International and domestic • General, excess and umbrella • Property • Environmental liability • Vacant dwellings • Workers’ compensation Call today. Michael Fitzpatrick 310-792-8449 [email protected] Wells Fargo Insurance Services USA, Inc. does not provide insurance products and services outside of the United States. Insurance products and services may be provided outside of the United States by foreign brokers licensed within their home venue. Foreign brokers are not employed by any Wells Fargo legal entity. Foreign brokers are individual insurance brokers responsible for compliance with all regulatory requirements of their home venue. In the United States, products and services are offered through Wells Fargo Insurance Services USA, Inc. and Safehold Special Risk, Inc., dba Safehold Special Risk & Insurance Services, Inc. in California, non-bank insurance agency affiliates of Wells Fargo & Company. Products and services are underwritten by unaffiliated insurance companies except crop and flood insurance in the United States, which may be underwritten by an affiliate, Rural Community Insurance Company. -

International SCAC Listing June 09, 2004

International SCAC Listing June 09, 2004 Carrier SCAC Code Carrier SCAC Code 3D TRUCKING 7TDT AIM CARRIBBEAN EXP 9AIM 4 4 WAY TRANSPORTATION FWYR AIM CARTAGE&LEASING AIMI 5SQZ 5SQZ AIR CANADA CARGO ACDA A & B FREIGHT LINE INC ABFL AIR CARGO EXPRESS 6CAX A & R TRANSPORT INC ANRI AIR CARGO TRANSPORTA AICP A & T TRUCKING CO ANTG AIR EXPRESS INTL ARXS A C DISTRIBUTING CO ACDD AIR EXPRESS INTL AXFF A C E COURIER SERVIC 9AQB AIR FREIGHT DELIVERY AFDS A D TRANSPORT EXPRES ADXR AIR FRT SPECIALISTS AFSO A DUIE PYLE INC PYLE AIR GROUND XPRESS IN 8ARX A J WEIGAND INC WEIG AIR LAND & SEA TRANS 8ADP A M EXPRESS INC AMXC AIR LAND TRANSPORT S APVC A M TRANSPORT 8AMT AIR LITE TRANSPORT I 7AAE A N DERINGER INC DANQ AIR RIDE EXPRESS INC 8ADX A ONE (1) PICKUP & D AOEQ AIR ROAD EXPRESS TRANS S ARXE A S A P EXPRESS INC ASXP AIR SEA FORWARDERS ASFF A TRANS DELIVERY SER ATDL AIR TRANSPORT INC 7AOI A X I ROAD AEXG AIR WISCONSIN WIAF A.B.C. MOTOR FREIGHT AOFI AIRBORNE FREIGHT CORPORA AIRB AAA COOPER TRANSPORTATIO AACT AIRCO GAS & GEAR 9AIZ AAROW MOVING & STORA ARWG AIRGROUP EXPRESS 9AGX ABC EXPRESS INC ABXI AIRWAY EXP COURIER 9BFX ABEL FREIGHT LINES ABEQ AIT FREIGHT SYSTEMS AIIH ABERDEEN EXPRESS INC ABNE AJAX TOOL INC 9AJO ABERDEEN TRUCK TERMI 9APX AKRON EXPRESS INC AKXP ABF FREIGHT SYSTEM INC ABFS AKZO CHEMICALS INC 9AKI ABLE TRANSIT ABEN ALASKA AIRLINES INC AKAL ACE DORAN HAULING & RIGG ACEH ALCOA FUJIKURA MANUF 7AFJ ACE FORWARDING 7ACF ALEXANDER INTERNATIO AXNI ACE TRANSPORTATION I ATPH ALGO-EXPEDITE AGOE ACME DELIVERY SERVIC ADEO ALL ONTARIO COURIER 6AOC ACME -

SCAC Carrier Name CSI AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. 77.56

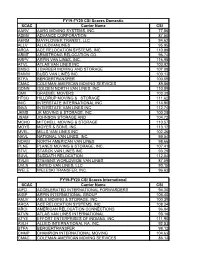

FY19-FY20 CSI Scores Domestic SCAC Carrier Name CSI AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. 77.56 ADMV ADVANCE CORPORATION 87.50 AERM MAYFLOWER TRANSIT, LLC 94.62 ALLV ALLIEDVANLINES 95.95 ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. 110.89 ARMT ARMSTRONG RELOCATION CO. 96.74 ARPV ARPIN VAN LINES, INC. 116.98 ATVL ATLAS VAN LINES INC 103.92 BMSG J BARBER MOVING AND STORAGE 107.08 BMVM BUDD VAN LINES INC. 100.13 BTFA BERGERTRANSFER 100.59 CMAC COLEMAN AMERICAN MOVING SERVICES 89.86 GDNN GOLDEN NORTH VAN LINES, INC. 110.89 GMII GRAEBEL MOVERS 103.38 HTSQ HILLDRUP MOVING & STORAGE 111.62 INIC INTERSTATE INTERNATIONAL INC 114.90 INVA INTERSTATE VAN LINES INC 112.74 JKMS JK MOVING & STORAGE, INC. 100.28 JSAM JOHNSON STORAGE AND 104.72 MCHO MITCHELL MOVING & STORAGE 110.57 MOYS MOYER & SONS, INC. 113.12 MVEL MILLS VAN LINES INC 102.36 NAVL NATIONAL VAN LINES, INC. 99.54 NOAM NORTH AMERICAN VAN LINES 98.66 PLNE PLANES MOVING & STORAGE, INC. 107.41 STVL STARCK VAN LINES INC 93.29 SUVL SUDDATH RELOCATION 112.04 SVLM STEVENS WORLDWIDE VAN LINES 87.59 UVLN UNITED VAN LINES, LLC 90.15 WELE WELESKI TRANSFER, INC. 96.63 FY19-FY20 CSI Scores International SCAC Carrier Name CSI AIFD ACCELERATED INTERNATIONAL FORWARDERS 94.36 AIGP ARPIN INTERNATIONAL GROUP 106.40 AMJV ABLE MOVING & STORAGE, INC. 100.39 ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. 108.34 AROI AMERICAN RELOCATION CONNECTIONS 96.84 ATVN ATLAS VAN LINES INTERNATIONAL 93.16 ATYE EFFORT ENTERPRISES OF INDIANA, INC. 111.90 AVLH ALLIED INTERNATIONAL NA, INC. -

1 United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District Of

08-10375-jmp Doc 700 Filed 09/02/09 Entered 09/02/09 16:46:36 Main Document Pg 1 of 15 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------------------- : Chapter 11 In re : : Case No. 08-10375 (JMP) DJK Residential LLC, et. al., : : (Jointly Administered) Debtors. : : --------------------------------------------------------------- MEMORANDUM DECISION GRANTING OBJECTION TO CLAIM NUMBER 138 FILED ON BEHALF OF IFL INDUSTRIES, INC., AIRQUEST INDUSTRIES, INC. AND WILLIAM D. OLSON KIRKLAND & ELLIS, LLP Attorneys for Debtors 200 East Randolph Drive Chicago, IL 60601 Adam Paul, Esq. KIRKLAND & ELLIS, LLP Attorneys for Debtors 555 California Street San Francisco, CA 94104 Eliot A. Adelson, Esq. ZIMMERMAN REED, PLLP Attorneys for Claimants, IFL Industries, Inc., Airquest Industries, Inc. and William D. Olson 14646 North Kierland Boulevard, Ste. 145 Scottsdale, AZ 85254 Barry G. Reed, Esq. 1 08-10375-jmp Doc 700 Filed 09/02/09 Entered 09/02/09 16:46:36 Main Document Pg 2 of 15 JAMES M. PECK UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY JUDGE Introduction Debtors have objected (the “Objection”) to claim number 138 (the “Claim”) filed on behalf of IFL Industries, Inc, Airquest Industries, Inc. and William D. Olson (collectively the “Claimants”) seeking to dismiss, disallow and expunge the Claim. (ECF Doc. # 660.) The Claim is unliquidated and seeks substantial unspecified damages of almost forty million dollars due to allegedly illegal incentives offered for using particular moving companies within the specialized -

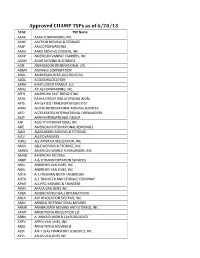

Approved CHAMP Tsps As of 6/20/13 SCAC TSP Name AAAA AAAA FORWARDING, INC

Approved CHAMP TSPs as of 6/20/13 SCAC TSP Name AAAA AAAA FORWARDING, INC. AAIM AACTION MOVING & STORAGE AALF AALCO FORWARDING AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. AAVP AMERICAN VANPAC CARRIERS, INC. ACMH ACME MOVING & STORAGE ADIF AMASSADOR INTERNATIONAL LTD ADMV ADVANCE CORPORATION ADOL AMBASSADOR RELOCATIONS INC AEQL ACCESS RELOCATION AERM MAYFLOWER TRANSIT, LLC AFDG ATLAS FORWARDING, INC. AFFH AMERICAN FAST FREIGHT INC AFIW PASHA GROUP DBA AFI/PASHA WORL AFTS AFFILIATED TRANSPORTATION SYST AHIM ALOHA INTERNATIONAL MOVING SERVICES AIFD ACCELERATED INTERNATIONAL FORWARDERS AIGP ARPIN INTERNATIONAL GROUP AIIF AGILITY INTERNATIONAL INC AIRE AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL REMOVALS ALDS ALEXANDERS MOVING & STORAGE ALLV ALLIEDVANLINES ALRQ ALL AMERICA RELOCATION, INC. AMJV ABLE MOVING & STORAGE, INC. AMNW AMERICAN WORLD FORWARDERS, INC. AMRB AMERICAN RED BALL ANBP A & B TRANSPORTATION SERVICES ANVL ANDREWS VAN LINES, INC. ANVL ANDREWS VAN LINES, INC. AOFA A-1 FREEMAN NORTH AMERICAN AOTA A-1 TRANSFER AND STORAGE COMPNAY APMT ALL PRO MOVING & TRANSFER APVN APACA VAN LINES INC ARBA AMERICAN RED BALL INTERNATIONA ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. ARIM ARNOLD INTERNATIONAL MOVERS ARMR ARMBRUSTER MOVING AND STORAGE, INC. ARMT ARMSTRONG RELOCATION CO. ARNA A. ARNOLD WORLD CLASS RELOCATI ARPV ARPIN VAN LINES, INC. ARSG ARMSTRONG MOVING & ASST AIR 7 SEAS TRANSPORT LOGISTICS, INC. ATVL ATLAS VAN LINES INC ATVN ATLAS VAN LINES INTERNATIONAL ATYE EFFORT ENTERPRISES OF INDIANA, INC. AVAS AMERICAN VAN SERVICE, INC. AVLH ALLIED INTERNATIONAL NA, INC. BAIP PARKER K. BAILEY & SONS, INC. BAMO BARNES MOVING & STORAGE CO. BARK BARKLEY TRUCK LINES, INC. BBAF B & B MOVERS, INC. BBMS BRANTLEY BROTHERS MOVING & BEKM BEKINS A-ONE MOVERS BEKS BEKINS NORTHWEST BEMJ BEMIDJI TRANSFER, INC. -

Central Freight Lines Inc

Consolidation Elevates Companies On Top 100 For-Hire Carriers List By Daniel P. Bearth ■ Daseke Inc. (No. 49) added to its collection of flatbed car- Senior Features Writer riers with Texas-based Lone Star Transportation. ■ Mullen Group (No. 57) acquired Gardewine Group onsolidation continues to reshape trucking, and the and contributed its interest in Mill Creek Motor Freight 2015 edition of the TRANSPORT TOPICS Top 100 list for 30% equity in Kriska Transportation Group. C of the largest U.S. and Canadian for-hire carriers ■ Dicom Transportation Group (No. 92) acquired Time provides plenty of examples of how the trend is playing out. Logistics Couriers and Modern Forwarding, expanding its Competition between UPS Inc., which ranks No. 1, and expedited delivery service in the United States and resulting FedEx Corp., which ranks No. 2, is expected to intensify in Montreal-based Dicom’s first appearance on the for-hire in the wake of FedEx’s February acquisition of U.S. dis- TT100. tribution specialist Genco and its pending acquisition of The number of companies with annual revenue of at least Dutch-owned express carrier TNT Express. $1 billion increased to 35 from 30 a year ago. Companies Not to be outdone, XPO Logistics snapped up drayage that crossed that threshold for the first time in 2014 in- firm Bridge Terminal Transport in May and a month later cluded XPO Logistics, Penske Logistics, Knight Trans- wrapped up a deal to acquire European-based freight car- portation, Forward Air Corp. and Lynden Inc. rier and distribution specialist Norbert Dentressangle. Data for all companies on the list come from company The acquisition of BTT, which ranked No.