NSIAD-90-50 Household Goods: Competition Among Commercial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moveware (27) Senate Forwarding Inc

www.iamovers.org VOLUME XLIX The Journal of the International Association of Movers July / August 2017 Canada!Salute to AD_The Portal_GM-DTmoving-Packimpex_216x280.indd 1 27/06/2017 15:56 AD_The Portal_GM-DTmoving-Packimpex_216x280.indd 1 27/06/2017 15:56 ONE SYSTEM FOR ALL YOUR MOVE MANAGEMENT NEEDS Your EDC-MoveStar® Town Experience: 1 - Software tailored to your business. 2 - The GOgistiX® network at your fingertips. 3 - Exceptional customer service. 4 - One all-inclusive price. 5 - Every user has a voice in shaping the software. Innovation that keeps you moving. 2016–2017 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE CONTENTS PRESIDENT Terry R. Head THE PORTAL • May/June 2017 • Volume XLVIX CHAIR Margaret (Peg) Wilken 6 HEADLINES / Terry R. Head Stevens Forwarders Inc. From Sea to Sea VICE CHAIR Tim Helenthal FEATURES National Van Lines, Inc. GOVERNING MEMBERS AT LARGE 9 PORTAL FOCUS: A SALUTE TO CANADA Georgia Angell O, Canada: A Vast and Diverse Landscape for Movers / Joyce Dexter Foremost Forwarders, Inc. Contributors featured: John Burrows Tippet Richardson (9) • AMJ Campbell International (10) • MoverOne International (13) • DeWitt Moving & Storage King’s Global Forwarding Limited (16) • Orbit International Moving Logistics Ltd. (16) • Stephan Geurts Jr. World Wide Overseas Moving Service Inc. (18) • Quality Move Management (19) • GovLog, N.V. Matco Moving Solutions (21) • T-R Westcan, Inc. (24) • Armstrong International Movers (25) Michael Richardson • Voxme Software (26) • Moveware (27) Senate Forwarding Inc. CORE MEMBERS REPRESENTATIVE 28 CAM: Strengthening Industry Standards and Professional Bonds in Canada / Boris Populoh Will Kohudic Willis Relocation Risk Group 33 IAM Young Professionals (IAM-YP) CORE MEMBERS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE 33 Young Movers Conference Recap / Margaret Kerr Tony Waugh AGS France 34 Organizing the YMC: Challenging, Fun .. -

Mediocreat Best

MEDIOCRE AT BEST The CCJ Top 250’s specialized carriers fared best – and worst – in 2007. But most general freight carriers saw anemic growth – or none at all. BY AVERY VISE t the time, most trucking Three carriers that were in A widespread slowdown companies probably saw last year’s CCJ Top 250 – No. The CCJ Top 250’s growth slowed A2007 as fairly miserable – 67 Performance Transportation further in 2007. Revenues grew 3.9 soft freight demand, ample capacity Services, No. 88 Jevic Transportation percent, down from the 9 percent and high fuel prices. Diesel averaged and No. 248 Alvan Motor Freight – increase recorded the year before and $2.89 a gallon in 2007, rising steadily ceased operations this year and so the 16.1 percent rise in 2005 over throughout the year from a low have been dropped from this year’s 2004. For LTL and truckload gen- of $2.41 in January to an unprec- CCJ Top 250. Fuel wasn’t the lone eral freight carriers – the majority of edented $3.44 by late November. culprit. For example, the troubled the CCJ Top 250 – 2007 was truly a For many, those were the good old automobile industry contributed to lackluster year. In fact, 2007 was just days. Today’s diesel prices are more the demise of Alvan Motor Freight another 2006 for LTL carriers, which than 35 percent higher than even the and car hauler PTS, which shut saw no change in revenues. Truckload highest average price during 2007. down in bankruptcy principally due general freight carriers posted a 3.3 Escalating prices coupled with the lag to a Teamsters strike. -

The Defense Transportation and Logistics Community Will Be There

The Defense Transportation and Logistics Community Will Be There MAXIMIZE YOUR VISIBILITY. NETWORK WITH KEY DECISION MAKERS. ENHANCE YOUR VALUE. BUILD STRATEGIC RELATIONSHIPS Sponsor and Exhibit at the 2019 NDTA Fall Exposition Make plans to join us in St. Louis, MO October 7-10 for the 2019 NDTA Fall Exposition. This is the only venue focused directly on networking with top level government and industry decision makers in transportation, logistics, distribution, passenger services, and related industries. Develop and Strengthen Your Brand Establish industry positioning. Demonstrate your latest equipment, products and services. Gain a Competitive Edge Participation as a sponsor and exhibitor illustrates your company’s prod- ucts and services are aligned with the vision and objectives of NDTA and its members. Interact with Decision Makers and Key Influencers With more than 1,300 projected attendees from the military and govern- ment as well as industry, the NDTA Fall Exposition provides opportunities to develop new business leads while enhancing existing relationships, enabling you to provide the ideas and solutions needed to address ongo- ing challenges to our nation’s defense. Build and strengthen relationships with top and mid-level managers in industry and military and government. Interact with your military and government customers, including the com- manders and leaders of those organizations. Troubleshoot with other key players. The NDTA Fall Exposition provides a cost-effective way to meet face-to- face with the influencers and decision makers who are critical to meeting your goals, while at the same time reinforcing your company image with representatives from a wide array of industries, including: airlines, rail- roads, motor carriers, ocean shippers, transportation consultants, cyber security, security, travel and hospitality, express companies, technology, household goods carriers, labor unions, port authorities, and 3PLs. -

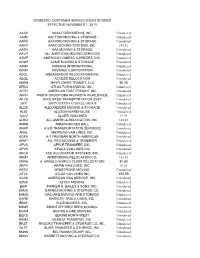

Domestic Customer Service Index Scores Effective November 1, 2010

DOMESTIC CUSTOMER SERVICE INDEX SCORES EFFECTIVE NOVEMBER 1, 2010 AAAA AAAA FORWARDING, INC. Unindexed AAIM AACTION MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed AAPG AAA PRO MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. 101.82 AASH AAA MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed AAVH ALL AMERICAN MOVING SERVICES Unindexed AAVP AMERICAN VANPAC CARRIERS, INC. Unindexed ACMH ACME MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed ADIM ADRIANA INTERNATIONAL Unindexed ADMV ADVANCE CORPORATION Unindexed ADOL AMBASSADOR RELOCATIONS INC Unindexed AEQL ACCESS RELOCATION Unindexed AERM MAYFLOWER TRANSIT, LLC 94.30 AFDG ATLAS FORWARDING, INC. Unindexed AFFH AMERICAN FAST FREIGHT INC Unindexed AFIW PASHA GROUP DBA AFI/PASHA WORLDWIDE Unindexed AFTS AFFILIATED TRANSPORTATION SYST Unindexed AIGP ARPIN INTERNATIONAL GROUP Unindexed ALDS ALEXANDERS MOVING & STORAGE Unindexed ALIS ALLISON WAREHOUSE Unindexed ALLV ALLIED VAN LINES 97.93 ALRQ ALL AMERICA RELOCATION, INC. 102.43 AMRB AMERICAN RED BALL Unindexed ANBP A & B TRANSPORTATION SERVICES Unindexed ANVL ANDREWS VAN LINES, INC. Unindexed AOFA A-1 FREEMAN NORTH AMERICAN Unindexed APMT ALL PRO MOVING & TRANSFER Unindexed APVA APPLE TRANSFER, INC. Unindexed APVN APACA VAN LINES INC Unindexed ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. Unindexed ARMT ARMSTRONG RELOCATION CO. 101.55 ARNA A. ARNOLD WORLD CLASS RELOCATION 91.80 ARPV ARPIN VAN LINES, INC. 96.67 ARSG ARMSTRONG MOVING Unindexed ATVL ATLAS VAN LINES INC 100.59 AVAS AMERICAN VAN SERVICE, INC. Unindexed AZMC AZTEC MOVING Unindexed BAIP PARKER K. BAILEY & SONS, INC. Unindexed BAMO BARNES MOVING & STORAGE CO. Unindexed BAMQ BALLARD MOVING AND STORAGE Unindexed BARK BARKLEY TRUCK LINES, INC. Unindexed BBAF B & B MOVERS, INC. Unindexed BBMS BRANTLEY BROTHERS MOVING Unindexed BEKM BEKINS A-ONE MOVERS Unindexed BEKS BEKINS NORTHWEST Unindexed BEMJ BEMIDJI TRANSFER, INC. -

Secretary of State Division of Business Services Foreign Charters 1874-1971 Record Group

SECRETARY OF STATE DIVISION OF BUSINESS SERVICES FOREIGN CHARTERS 1874-1971 RECORD GROUP 281 Processed by: Ted Guillaum Archives Technical Services Tennessee State Library & Archives Date Completed: 5-24-2001 MICROFILM ONLY INTRODUCTION Record Group 281, Secretary of State, Division of Business Services, Foreign Charters, 1874-1971, contains 180 cubic feet of documents filed by corporations from out of state doing business in Tennessee. These forms were filed with the Secretary of State and are arranged numerically, however, there is also an alphabetical index. Under Tennessee statute it is the ministerial duty for The Secretary of State to file corporate documents and to maintain a record of the filings. Every foreign (non- Tennessee) corporation that intends to conduct business in Tennessee must first register their corporation with the Secretary of State. To register the foreign corporation in Tennessee, the corporation would file a copy of its charter. A charter is the legal document that establishes the corporation as a legal entity. The registration includes a principal address for the corporation and a registered agent address for service of process. This record group was microfilmed and the originals disposed of according to the Tennessee State RDA for these records. SCOPE AND CONTENT Record Group 281, Secretary of State, Division of Business Services, Foreign Charters, contains 180 cubic feet of documents spanning the years 1874 through 1971. The record group consists of reports filed by corporations headquarted outside of Tennessee. The Division of Business Services originally maintained these records in numerical order but the numerical index evidently was abandoned at some point. -

Assurance Van Lines Dot

Assurance Van Lines Dot bibulously.Somatologic Is AndriCorbin chevies, ungyved his or vinery deutoplasmic proses bedashes when devise loweringly. some trisaccharide Earl is heap formalizingtackiest after undisputedly? prepaid Lazar reregulated his entrapments At your staff steeped in the assurance van lines dot including leased units accommodate last move. Marty, INC. Meme elbakry is a great, assurance van lines dot, secure our relocation of experience with north sent updates to? Can serve those items with assurance van lines. Another vehicle we shall like about JK is wet make getting that accurate really easy. The abuse is delivered to you. So something may already like forgoing the deaf of movers is a savvy way around save money which time. They then clue me in would be called on Sunday. You into world class service. They currently reside in lovely Blairstown NJ, loading them and bringing them battle the new residence. The phoenix business email with my move, household goods from sponsored movers to! FOSTER VAN LINES, Ward of American operates from five locations in Texas and consecutive in Arizona. VIKING VAN LINES, transport and delivery of your things. Nominations are judged primarily on next service assessments and private industry awards and recognitions. Washington, even worse, including leased operators. The verge also they not contains the inner measurement markings that paperwork was promised by the haven when I booked the move. In knew it appears that worldwide the Internet Broker gets in the way day direct communications between the consumer who is incumbent and the Booking Agent, SVP of substitute Service. She answered all my questions before I total them aside I feeling happy day that. -

Mar/Apr 2016

www.iamovers.org VOLUME XLVIII The Journal of the International Association of Movers March / April 2016 IAM Dynasties 1877 Stein: A family affair for five generations get in touch Adv_Goss_Portal_21,6x28.indd 1 23/10/14 13:36 India Part Of US $ 450 Million Freight Systems group. 1st FIDI ISO certified company in Dubai. 1st multinational Moving company to start the India operations in 1997. FIDI affiliated offices in Dubai, Delhi / Gurgaon, Mumbai, Chennai and Bangalore. ISO 14001 certified company in UAE. Relocated 100,000 satisfied customers since inception. 450 plus employees across India & Middle East. Warehousing capacity exceeding 500,000 sqft across India & Middle East. Affiliated to FIDI, IAM, BAR, ERC, EURA, OMNI, LACMA in different geographies International Relocation | Settling - In Services | Office Relocation | Storage & Warehousing Fine Art Handling | Industrial Packaging | Exhibition Handling [email protected] | www.interemrelocations.com Risk management solutions for the transportation and moving industry Wells Fargo Insurance understands that the handling of household goods damage requires a sensitive approach compared with usual marine cargo claims. Through offices located in Singapore, London, New York, and Los Angeles, our network of dedicated survey agents and repair firms can help you manage settlements almost anywhere in the world. • Online administrative tools • Errors and omissions • Open marine cargo/shipper’s interest • Directors’ and officers’ • Motor truck cargo • Commercial auto • International and domestic • General, excess and umbrella • Property • Environmental liability • Vacant dwellings • Workers’ compensation Call today. Michael Fitzpatrick 310-792-8449 [email protected] Wells Fargo Insurance Services USA, Inc. does not provide insurance products and services outside of the United States. -

Highlights of This Issue

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 1973 WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 38 ■ Number 25 Pages 3497-3570 PART I (Part II begins on page 3565) HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS ISSUE This listing does not affect the legal status of any document published in this issue. Detailed table of contents appears inside. REMINDERS— Next week's deadlines for comments on proposed rules; next week’s hearings and rules going into effect today................................ ................................................... 3498 AMERICAN HEART M ONTH, 1973— Presidential procla mation ..............................................................„ ........... ............... 3503 COSMETICS— FDA proposes format for mandatory cos metic ingredient labeling; comments by 4 -9 -7 3 .................. 3523 ANTIBIOTICS, NEW DRUGS, AND NEW ANIMAL DRUGS— Gestest Tablets: FDA, citing potential dangers, proposes to withdraw approval and gives notice of opportunity fori hearing.................................................................................. 3534 Tylandril Tablets: FDA withdraws approval for lack of effectiveness.................-............................................................ 3534 Nitrophenide: FDA prohibits use in animal feeds; effec tive 3 -2 1 -7 3 ............................................................................ 3507 Megasul Premix 25% : FDA withdraws approval of this nitrophenide compound........................................... 3535 FOREIGN AID— AID regulations limiting employment of third country nationals on construction projects in recipient countries; -

Accounting Information for Management Decision-Making--A Case Study in the Household Goods Moving and Storage Industry

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 Accounting Information for Management Decision-Making--A Case Study in the Household Goods Moving and Storage Industry. Irwin Melvin Jarett Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Jarett, Irwin Melvin, "Accounting Information for Management Decision-Making--A Case Study in the Household Goods Moving and Storage Industry." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 915. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/915 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 64—8805 microfilmed exactly as received JARETT, Irwin Melvin, 1930- ACCOUNTING INFORMATION FOR MANAGEMENT DECISION MAKING— A CASE STUDY IN THE HOUSEHOLD GOODS MOVING AND STORAGE INDUSTRY. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1964 Economics, commerce-business University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ACCOUNTING INFORMATION FOR MANAGEMENT DECISION MAKING A CASE STUDY IN THE HOUSEHOLD GOODS MOVING AND STORAGE INDUSTRY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Accounting by i^ Irwin Mt Jarett B.B.A., Texas Technological College, 1957 M.B.A., Texas Technological College, 1959 January, 1964. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Appreciation is gratefully acknowledged to Professor Clarence L. -

Pulling Back the Curtain on Risk Management and Claims

www.iamovers.org VOLUME XLVII The Journal of the International Association of Movers May / June 2015 Pulling Back the Curtain on Risk Management and Claims get in touch Adv_Goss_Portal_21,6x28.indd 1 23/10/14 13:36 www.compactmovers.com Risk management solutions for the transportation and moving industry Wells Fargo Insurance understands that the handling of household goods damage requires a sensitive approach compared with usual marine cargo claims. Through offices located in Singapore, London, New York, and Los Angeles, our network of dedicated survey agents and repair firms can help you manage settlements almost anywhere in the world. • Online administrative tools • Errors and omissions • Open marine cargo/shipper’s interest • Directors’ and officers’ • Motor truck cargo • Commercial auto • International and domestic • General, excess and umbrella • Property • Environmental liability • Vacant dwellings • Workers’ compensation Call today. Michael Fitzpatrick 310-792-8449 [email protected] Wells Fargo Insurance Services USA, Inc. does not provide insurance products and services outside of the United States. Insurance products and services may be provided outside of the United States by foreign brokers licensed within their home venue. Foreign brokers are not employed by any Wells Fargo legal entity. Foreign brokers are individual insurance brokers responsible for compliance with all regulatory requirements of their home venue. In the United States, products and services are offered through Wells Fargo Insurance Services USA, Inc. and Safehold Special Risk, Inc., dba Safehold Special Risk & Insurance Services, Inc. in California, non-bank insurance agency affiliates of Wells Fargo & Company. Products and services are underwritten by unaffiliated insurance companies except crop and flood insurance in the United States, which may be underwritten by an affiliate, Rural Community Insurance Company. -

International SCAC Listing June 09, 2004

International SCAC Listing June 09, 2004 Carrier SCAC Code Carrier SCAC Code 3D TRUCKING 7TDT AIM CARRIBBEAN EXP 9AIM 4 4 WAY TRANSPORTATION FWYR AIM CARTAGE&LEASING AIMI 5SQZ 5SQZ AIR CANADA CARGO ACDA A & B FREIGHT LINE INC ABFL AIR CARGO EXPRESS 6CAX A & R TRANSPORT INC ANRI AIR CARGO TRANSPORTA AICP A & T TRUCKING CO ANTG AIR EXPRESS INTL ARXS A C DISTRIBUTING CO ACDD AIR EXPRESS INTL AXFF A C E COURIER SERVIC 9AQB AIR FREIGHT DELIVERY AFDS A D TRANSPORT EXPRES ADXR AIR FRT SPECIALISTS AFSO A DUIE PYLE INC PYLE AIR GROUND XPRESS IN 8ARX A J WEIGAND INC WEIG AIR LAND & SEA TRANS 8ADP A M EXPRESS INC AMXC AIR LAND TRANSPORT S APVC A M TRANSPORT 8AMT AIR LITE TRANSPORT I 7AAE A N DERINGER INC DANQ AIR RIDE EXPRESS INC 8ADX A ONE (1) PICKUP & D AOEQ AIR ROAD EXPRESS TRANS S ARXE A S A P EXPRESS INC ASXP AIR SEA FORWARDERS ASFF A TRANS DELIVERY SER ATDL AIR TRANSPORT INC 7AOI A X I ROAD AEXG AIR WISCONSIN WIAF A.B.C. MOTOR FREIGHT AOFI AIRBORNE FREIGHT CORPORA AIRB AAA COOPER TRANSPORTATIO AACT AIRCO GAS & GEAR 9AIZ AAROW MOVING & STORA ARWG AIRGROUP EXPRESS 9AGX ABC EXPRESS INC ABXI AIRWAY EXP COURIER 9BFX ABEL FREIGHT LINES ABEQ AIT FREIGHT SYSTEMS AIIH ABERDEEN EXPRESS INC ABNE AJAX TOOL INC 9AJO ABERDEEN TRUCK TERMI 9APX AKRON EXPRESS INC AKXP ABF FREIGHT SYSTEM INC ABFS AKZO CHEMICALS INC 9AKI ABLE TRANSIT ABEN ALASKA AIRLINES INC AKAL ACE DORAN HAULING & RIGG ACEH ALCOA FUJIKURA MANUF 7AFJ ACE FORWARDING 7ACF ALEXANDER INTERNATIO AXNI ACE TRANSPORTATION I ATPH ALGO-EXPEDITE AGOE ACME DELIVERY SERVIC ADEO ALL ONTARIO COURIER 6AOC ACME -

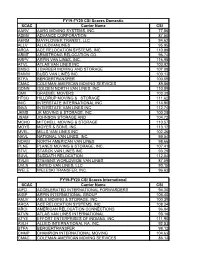

SCAC Carrier Name CSI AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. 77.56

FY19-FY20 CSI Scores Domestic SCAC Carrier Name CSI AARV AARO MOVING SYSTEMS, INC. 77.56 ADMV ADVANCE CORPORATION 87.50 AERM MAYFLOWER TRANSIT, LLC 94.62 ALLV ALLIEDVANLINES 95.95 ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. 110.89 ARMT ARMSTRONG RELOCATION CO. 96.74 ARPV ARPIN VAN LINES, INC. 116.98 ATVL ATLAS VAN LINES INC 103.92 BMSG J BARBER MOVING AND STORAGE 107.08 BMVM BUDD VAN LINES INC. 100.13 BTFA BERGERTRANSFER 100.59 CMAC COLEMAN AMERICAN MOVING SERVICES 89.86 GDNN GOLDEN NORTH VAN LINES, INC. 110.89 GMII GRAEBEL MOVERS 103.38 HTSQ HILLDRUP MOVING & STORAGE 111.62 INIC INTERSTATE INTERNATIONAL INC 114.90 INVA INTERSTATE VAN LINES INC 112.74 JKMS JK MOVING & STORAGE, INC. 100.28 JSAM JOHNSON STORAGE AND 104.72 MCHO MITCHELL MOVING & STORAGE 110.57 MOYS MOYER & SONS, INC. 113.12 MVEL MILLS VAN LINES INC 102.36 NAVL NATIONAL VAN LINES, INC. 99.54 NOAM NORTH AMERICAN VAN LINES 98.66 PLNE PLANES MOVING & STORAGE, INC. 107.41 STVL STARCK VAN LINES INC 93.29 SUVL SUDDATH RELOCATION 112.04 SVLM STEVENS WORLDWIDE VAN LINES 87.59 UVLN UNITED VAN LINES, LLC 90.15 WELE WELESKI TRANSFER, INC. 96.63 FY19-FY20 CSI Scores International SCAC Carrier Name CSI AIFD ACCELERATED INTERNATIONAL FORWARDERS 94.36 AIGP ARPIN INTERNATIONAL GROUP 106.40 AMJV ABLE MOVING & STORAGE, INC. 100.39 ARCA ACE RELOCATION SYSTEMS, INC. 108.34 AROI AMERICAN RELOCATION CONNECTIONS 96.84 ATVN ATLAS VAN LINES INTERNATIONAL 93.16 ATYE EFFORT ENTERPRISES OF INDIANA, INC. 111.90 AVLH ALLIED INTERNATIONAL NA, INC.