2349-6746 Issn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syllabi Book Ix

ISLAMIAH COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) VANIYAMBADI – 635 752 (AIDED & SELF FINANCE) SYLLABI BOOK IX 10TH ACADEMIC COUNCIL MEETING (For the UG & PG Candidates Admitted from 2018-2019) Th 04 FEBRUARY 2018 1 Part-I Credit 5 SEMESTER I Language Hrs./Week 6 UG - FOUNDATION COURSE Elective Course Exam Hrs. 3 (All UG I Year From 2018-19 onwards) Urdu Paper I - PROSE, GRAMMER & COURSE TITLE U8FUR101 LETTER WRITING UNIT I 1. SAIR PAHLAY DARWESH KI - Meer Amman Dehlavi 2. Ism aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to the Principal Seeking leave UNIT II 1. GHALIB KE AKHLAQ -O- AADAT - Moulana Althaf Hussain Hali 2. Fe'l aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to the father/guardian asking money for payment of college fees UNIT III 1. BEHS-O-TAKRAR - Sir Syed Ahmed Khan 2. Sifat aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to a friend inviting him to your sister's marriage UNIT IV 1. KHAWAJA MOINUDDEEN CHISTI – Shebaz Hussain 2. Zameer aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to the manager of a firm seeking employment UNIT V 1.SAWERAY JO KAL MERI AANKH KHULI – Putars Bukhari 2. Jins aur Uske Aqsaam 3. Letter to a publisher of a book seller placing order for books. Books for reference: URDU TEXT BOOK CUM WORK BOOK Published by the Department of Urdu & Arabic Islamiah College(Autonomous), Vaniyambadi 2 Part-I Credit 5 SEMESTER II Language Hrs./Week 6 UG - FOUNDATION COURSE Elective Course Exam Hrs. 3 (All UG I Year From 2018-19 onwards) URDUPAPER II- GHAZALIAT, MANZOOMAT , COURSE TITLE U8FUR201 RUBAIYAT &TRANSLATION UNIT - I 1. MEER TAQI MEER – Ulti hogayeen Sab tadbeerein kuch na dawa nay kam kiya 2. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Children and Childhood in the Madras Presidency, 1919-1943 Catriona Ellis Doctor of Philosophy History, Classics and Archaeology The University of Edinburgh 2016 1 Abstract This thesis interrogates the emergence of a universal modern idea of childhood in the Madras Presidency between 1920 and 1942. It considers the construction and uses of ‘childhood’ as a conceptual category and the ways in which this informed intervention in the lives of children, particularly in the spheres of education and juvenile justice. Against a background of calls for national self-determination, the thesis considers elite debates about childhood as specifically ‘Indian’, examining the ways in which ‘the child’ emerged in late colonial South India as an object to be reformed and as a ‘human becoming’ or future citizen of an independent nation. -

Fuzzy and Neutrosophic Analysis of Periyar's Views

FUZZY AND NEUTROSOPHIC ANALYSIS OF PERIYAR’S VIEWS ON UNTOUCHABILITY W. B. Vasantha Kandasamy Florentin Smarandache K. Kandasamy Translation of the speeches and writings of Periyar from Tamil by Meena Kandasamy November 2005 FUZZY AND NEUTROSOPHIC ANALYSIS OF PERIYAR’S VIEWS ON UNTOUCHABILITY W. B. Vasantha Kandasamy e-mail: [email protected] web: http://mat.iitm.ac.in/~wbv Florentin Smarandache e-mail: [email protected] K. Kandasamy e-mail: [email protected] Translation of the speeches and writings of Periyar from Tamil by Meena Kandasamy November 2005 2 Dedicated to Periyar CONTENTS Preface 5 Chapter One BASIC NOTION OF FCMs, FRMs, NCMs AND NRMS 1.1 Definition of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps 9 1.2 Fuzzy Cognitive Maps – Properties and Models 13 1.3 Fuzzy Relational Maps 18 1.4 An Introduction to Neutrosophy and some Neutrosophic algebraic structures 22 1.5 Neutrosophic Cognitive Maps 27 1.6 Neutrosophic Relational Maps — Definition with Examples 31 Chapter Two UNTOUCHABILITY: PERIYAR’S VIEW AND PRESENT DAY SITUATION A FUZZY AND NEUTROSOPHIC ANALYSIS 2.1 Analysis of untouchability due to Hindu religion using FCMs and NCMs 43 2.2 Analysis of discrimination faced by Dalits/ Sudras in the field of education as untouchables using FCMs and NCMs 58 2.3 Social inequality faced by Dalits and some of the most backward classes - an analysis using FCM and NCM 66 4 2.4 Problems faced by Dalits in the political arena due to discrimination – a FCM and NCM analysis 75 2.5 Study of Economic Status of Dalits due to untouchability using fuzzy and neutrosophic -

Indian Civil Service Examinations and Dalit Intervention in British India

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Indian Civil Service Examinations and Dalit Intervention in British India STALIN RAJANGAM A B RAJASEKARAN Stalin Rajangam ([email protected]) is a Dalit writer based in Madurai. A B Rajasekaran ([email protected]) is an intellectual property attorney based in Chennai. Vol. 55, Issue No. 12, 21 Mar, 2020 During the independence movement in the mid-19th century, the Paraiyar Mahajana Sabha from Tamil Nadu prevailed upon the British government to reject the demand from the Indian elite to simultaneously hold exams for the Indian Civil Services in India in addition to London. Dalit organisations at that time felt that such a move would only enable the upper- caste Indians to monopolise the bureaucracy in India. Even as the nationalist consciousness was emerging during the Indian freedom movement, there were countermovements within and outside the ambit of the freedom struggle. Their demands, especially from socially disadvantaged groups, would seem anti-national today, or at variance with the objectives of the freedom movement. But, it is essentially due to these movements that modern India is what it is today. Tamil Nadu has been a pioneer in the social justice movement, besides its contribution to the freedom struggle. Dalits were the first to form mass organisations, based on modern social justice ideas, to secure social and political rights in Tamil Nadu, as early as the second half of the 19th century (Geetha and Rajadurai 2008: 54). These ideas continue to reverberate even in the political sphere of modern-day Tamil Nadu. The Dalits perceived the ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 colonial government as a benefactor in their struggle, and found ways to secure such benefits from the colonial authorities that would eventually relieve them from the oppressive caste system. -

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

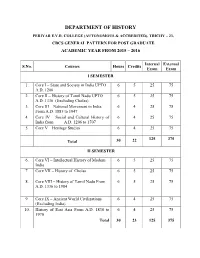

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

B.A., History Effective from the Year 2020-2021 Year: III Year Subject Code: U18MHS501 Semester: V Major - 9 Title: HISTORY of EUROPE from 1453 A.D

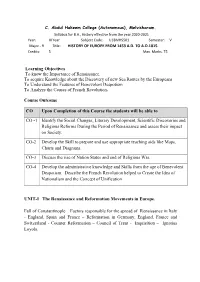

C. Abdul Hakeem College (Autonomous), Melvisharam. Syllabus for B.A., History effective from the year 2020-2021 Year: III Year Subject Code: U18MHS501 Semester: V Major - 9 Title: HISTORY OF EUROPE FROM 1453 A.D. TO A.D.1815. Credits: 5 Max. Marks. 75 Learning Objectives To know the Importance of Renaissance. To acquire Knowledge about the Discovery of new Sea Routes by the Europeans To Understand the Features of Benevolent Despotism To Analyze the Causes of French Revolution. Course Outcome CO Upon Completion of this Course the students will be able to CO -1 Identify the Social Changes, Literary Development, Scientific Discoveries and Religious Reforms During the Period of Renaissance and assess their impact on Society. CO-2 Develop the Skill to prepare and use appropriate teaching aids like Maps, Charts and Diagrams. CO-3 Discuss the rise of Nation States and end of Religious War. CO-4 Develop the administrative knowledge and Skills from the age of Benevolent Despotism. Describe the French Revolution helped to Create the Idea of Nationalism and the Concept of Unification UNIT-I The Renaissance and Reformation Movements in Europe. Fall of Constantinople – Factors responsible for the spread of Renaissance in Italy - England, Spain and France – Reformation in Germany, England, France and Switzerland - Counter Reformation – Council of Trent - Inquisition – Ignatius Loyola. C. Abdul Hakeem College (Autonomous), Melvisharam. UNIT-II Colonial Expansion in the 15th and 16th Centuries. Geographical Discoveries of Portugal and Spain - Prince Henry - Christopher Columbus - Vasco-da-Gama – Impact of the Geographical Discoveries - New scientific Inventions –Mariner’s Compass – Spinning Jenny – Gun powder. -

Master of Philosophy in History

MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY SYLLABUS - 2007-09 ST. JOSEPH’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) (Nationally Reaccredited with A+ Grade / College with Potential for Excellence) TIRUCHIRAPPALLI - 620 002 TAMIL NADU, INDIA 2 ST. JOSEPH’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), TIRUCHIRAPPALLI - 620 002 DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (M. PHIL.) FULL TIME - AUTONOMOUS REGULATIONS GUIDELINES 1. ELIGIBILITY A Candidate who has qualified for the Master’s Degree in any Faculty of this University or of any other University recognized by the University as equivalent there to (including old Regulations of any University) subject to such conditions as may be prescribed therefore shall be eligible to register for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.) and undergo the prescribed course of study in a Department concerned. A candidate who has qualified for Master’s degree (through regular study / Distance Education mode / Open University System) with not less than 55% of marks in the concerned subject in any faculty of this university or any other university recognized by Bharathidasan University, shall be eligible to register for M.Phil. SC / ST candidates are exempted by 5% from the prescribed minimum marks. 2. DURATION The duration of the M.Phil. course shall be of one year consisting of two semesters for the full-time programme. 3. COURSE OF STUDY The course of study shall consist of Part - I : 3 Written Papers Part - II : 1 Written Paper and Dissertation. The three papers under Part I shall be : Paper I : Research Methodology Paper II : Advanced / General Paper in the Subject Paper III : Advanced Paper in the subject Paper I to III shall be common to all candidates in a course. -

Ambedkar and Political Reservation

Source : www.indianexpress.com Date : 2020-08-17 AMBEDKAR AND POLITICAL RESERVATION Relevant for: Developmental Issues | Topic: Rights & Welfare of STs, SCs, and OBCs - Schemes & their Performance, Mechanisms, Laws Institutions and Bodies In an interview to this paper, Prakash Ambedkar, grandson of B R Ambedkar, (IE, July 27) said, “Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar had envisaged reservation for SC/STs in Lok Sabha and state Assembly constituencies for just 10 years.” This is an erroneous interpretation and shows lack of understanding of Ambedkar’s ideology and his idea of political representation initiated 100 years ago, in 1919. In the run up for political representation of the oppressed millions of untouchables in India, Ambedkar’s efforts, along with those of the nominated untouchable members of the legislative councils in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta Presidencies, bore fruit in the 1920s. The colonial state was forced to nominate two members from among untouchables to the Round Table Conference in 1930 to state their position in the constitutional process which eventually led to the framing of the Government of India Act, 1935. Ambedkar and his colleague from Madras, Rettamalai Srinivasan, were able to convince the first Round Table deliberations in 1930 to accept elected representation through reserved seats and separate electorate method. When Mahatma Gandhi attended the second Round Table Conference in 1931, he initially opposed any representation by electoral process for the untouchables and later opposed the method of election, separate electorate (which was available to Muslims and other minorities). Gandhi’s opposition to the idea of separate electorate was that untouchables are an intrinsic part of the Hindu society. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

Religious Solidarity. Vanmam Resolves the Problems for Two Different Religious Communities I.E

Scholarly Research Journal for Interdisciplinary Studies, Online ISSN 2278-8808, SJIF 2016 = 6.17, www.srjis.com UGC Approved Sr. No.49366, MAR–APR, 2018, VOL- 5/44 RELIGIOUS SOLIDARITY IN VANMAM Khagendra Sethi, Ph. D. Asst. Professor (II), Dept. of English, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, India, Odisha [email protected] The objective of this paper is to show the religious solidarity in Bama’s Vanmam. Her other novels expose the religious disharmony and conflict between the Dalits and the upper castes. In this novel, Bama finds the futility of internal conflicts among themselves and lays foundation of unity and integrity. The dalits understand that they are victimised on the ground of their disunity. They are disintegrated and segregated in the name of caste and religion. They realize that they cannot get rid of the brand of their caste even after their conversion. Religious fighting and intolerance lead them to nowhere. At last they get to know that religious solidarity is the panacea for their community growth and peaceful living. The text will be analysed in the context of Tamil society and Tamil Dalit Literature. Keywords: Dalit literature, religious solidarity, marginalization Scholarly Research Journal's is licensed Based on a work at www.srjis.com The Dalit in Tamil Nadu are called as “Taazhhtappator or Odukkapattavar” previously, but Dalit is in more use. Due to Dravidian politics it comes to Tamil Nadu. Dalit literature has come to Tamil Nadu like other states or other languages such as Marathi, Kannad and so on. Due to Dravidian politics it comes to existence in Tamil Nadu till then it did not find its place in the domain of literature. -

Role of Rettaimalai Srinivasan in the Temple Entry Movement V

© 2018 IJRAR December 2018, Volume 5, Issue 4 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) ROLE OF RETTAIMALAI SRINIVASAN IN THE TEMPLE ENTRY MOVEMENT V. ARUNA Ph.D., Research Scholar, Department of History, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram, Tamilnadu, India. Abstract : In the early years of the 20th Century among social reformers in the Madras city. Srinivasan was born on 7th July 1859 at village Kozhialam in Madhauranthagam Taluka, Chengalpet district in Tamilnadu. His family was a farmer family; his father Rettaimalai was a poor Adi Dravida. Srinivasan had a keen interest in painting; hence he took advanced training at Coimbatore and became well versed in arts and painting. Rettamalai Srinivasan was one of greatest Scheduled Caste leader. He worked for their welfare. In the beginning he had connections with Theosophical society. This helped him very much when he started work for the betterment of his people form 1884. In 1888, he married Aranganayagi who was chosen as bride by his parents. His sister was given in marriage to Pandit Iyothee thass. In 1890, Srinivasan moved to Madras. For three years, he vigorously explored the possibilities of uplifting the so called Paraiyars and creating a dignity for them on equal terms with other castes. He undertook extensive tour of the Madras Presidency visiting Chidambaram, Kumbakonam, Tiruvarur, Tanjore and Trichy the temple cities which stand as symbols of the traditional culture of the Tamils. These were not logically correct and it was the selfishness of certain upper castes people who denied the fundamental right and liberty of the Untouchables. -

Iyothee Thass and Depressed Class Intellectuals's Print and Press Media in Liberation Struggle in Tamil Nadu

Indian Streams Research Journal Volume 2, Issue.12,Jan. 2013 ISSN:-2230-7850 Available online at www.isrj.net ORIGINAL ARTICLE IYOTHEE THASS AND DEPRESSED CLASS INTELLECTUALS'S PRINT AND PRESS MEDIA IN LIBERATION STRUGGLE IN TAMIL NADU K.VELMANGAI AND L .SELVAMUTHU KUMARASAMI Ph.D., Research Scholar in History Presidency College (Autonomous) Chennai Tamil Nadu Associate Professor in History Presidency College (Autonomous) Chennai Tamil Nadu Abstract: Iyothee Thass, a depressed class by birth and Buddhist by conviction , was an outstanding figure in the role to emancipate the Depressed Classes and women in Tamil Nadu. He initiated socio-cultural awakening which preceded the specular rise of the Dravidian Movement in the second decade of the Twentieth Century Tamil Nadu. An Idealogue and a cultural crusader, Iyothee Thass and a host of Depressed Class intellectuals of Tamil Nadu initiated a dozen of Tamil journals and magazines and ventilated novel ideas and their print and press activities opened a new ground in the subaltern struggle for identity, human dignity, equality, justice and above all social emancipation. Iyothee Thass and R.Srinivasan who started the journals, Tamilan and Parayan respectively heralded the 'Age of Struggle for Social Justice and Social Acceptance' in Tamil Nadu. Iyohtee Thass also spearheaded a campaign of press media for the liberation of women from the age old suppositious customs of the Hindu Society.He ran the popular Tamil Weekly, Tamilan, for years. Besides, he published scores of pamphlets and tracts by him and his associates which were widely circulated among Tamils everywhere. The articles and write- ups he contributed for Tamilan provide an idea of the astounding range of his concerns: caste hegemony, untoucbability and issues involved in census which are considered still great obstacles for the emancipation of Depressed classes and women.