This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syllabi Book Ix

ISLAMIAH COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) VANIYAMBADI – 635 752 (AIDED & SELF FINANCE) SYLLABI BOOK IX 10TH ACADEMIC COUNCIL MEETING (For the UG & PG Candidates Admitted from 2018-2019) Th 04 FEBRUARY 2018 1 Part-I Credit 5 SEMESTER I Language Hrs./Week 6 UG - FOUNDATION COURSE Elective Course Exam Hrs. 3 (All UG I Year From 2018-19 onwards) Urdu Paper I - PROSE, GRAMMER & COURSE TITLE U8FUR101 LETTER WRITING UNIT I 1. SAIR PAHLAY DARWESH KI - Meer Amman Dehlavi 2. Ism aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to the Principal Seeking leave UNIT II 1. GHALIB KE AKHLAQ -O- AADAT - Moulana Althaf Hussain Hali 2. Fe'l aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to the father/guardian asking money for payment of college fees UNIT III 1. BEHS-O-TAKRAR - Sir Syed Ahmed Khan 2. Sifat aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to a friend inviting him to your sister's marriage UNIT IV 1. KHAWAJA MOINUDDEEN CHISTI – Shebaz Hussain 2. Zameer aur Uski Qismein 3. Letter to the manager of a firm seeking employment UNIT V 1.SAWERAY JO KAL MERI AANKH KHULI – Putars Bukhari 2. Jins aur Uske Aqsaam 3. Letter to a publisher of a book seller placing order for books. Books for reference: URDU TEXT BOOK CUM WORK BOOK Published by the Department of Urdu & Arabic Islamiah College(Autonomous), Vaniyambadi 2 Part-I Credit 5 SEMESTER II Language Hrs./Week 6 UG - FOUNDATION COURSE Elective Course Exam Hrs. 3 (All UG I Year From 2018-19 onwards) URDUPAPER II- GHAZALIAT, MANZOOMAT , COURSE TITLE U8FUR201 RUBAIYAT &TRANSLATION UNIT - I 1. MEER TAQI MEER – Ulti hogayeen Sab tadbeerein kuch na dawa nay kam kiya 2. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

DHARMAPURI DISTRICT : ,-F U'^'F^’MTATO-^ II;.; '^Nt; : I ■: T > Jucacicaul ■'1-M;^ Id —!

GOVFMmi m o r vAFHLriA!3Fj DEPARTMENT CF ELEMENTARY EDUCATION THE DISTRICT PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMME DHARMAPURI DISTRICT : ,-f U'^'f^’MTATO-^ II;.; '^nt; : I ■: t > Jucacicaul ■'1-m;^ id —!.,,. c-ition. i7‘B, :.:;-i u ' ; = -uo Ivlarg, W i Ib.-jjtUid - QCi , ........ ■•. Date THE DISTMCT PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMME DHARMAPURI DISTRICT CONTENTS PAGE NO. CHAPTER - 1 PRIMARY EDUCATION IN THE DISTRICT OF DHARMAPURI 1-12 CHAPTER - II PROBLEMS AND ISSUES 13 - 19 CHAPTER - III THE PROJECT 20 - 27 RAFTER - IV COST OF THE PROJECT 28 - 33 CHAPTER - V MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE 34 - 36 i^ y ^ E R - VI BENEFITS AND RISKS 37 - 38 NIEPA DC D08630 'V a uLi, 1ft A lattitule of BducatiOQ.A{ ' ■■■•% and Administration. 7 'L 1 Aurobindo Marg, PROJECT PREPARATION ATTACHMENTS ANNEXURE -1 PAGE No Ta)le 1(a) Population of Dharmapuri District 39 TaHe 1(b) Effective Literacy rate by sex and comparative rate with other Districts TaUe 1(c) Enrolment Standardwise Tatle 1(d) Enrolment of S.C/S.T. students 42 Tade 2(a) Number of Institutions in the District Table 2(b) Number of Instioitions Blockwise 44 Table 2(c) Growth of schools 45 Table 2(d) Number of Institutions strengthwise 46 Tabje 2(e) Number of Institutions, Teachers strength and languagewise. 46 ANNEXURE-2 Table 2(a) Educational ladder at the Primary and upper primary level. 46-A Tabic 2(b) Organisation Chan of Basic Education at the District level. B,C,D Table 2(c) Block level administration (Details of supervisory stafO PAGE IWO).), Table 3(a) Expenditure Statement on Elementary 48 Education. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Fuzzy and Neutrosophic Analysis of Periyar's Views

FUZZY AND NEUTROSOPHIC ANALYSIS OF PERIYAR’S VIEWS ON UNTOUCHABILITY W. B. Vasantha Kandasamy Florentin Smarandache K. Kandasamy Translation of the speeches and writings of Periyar from Tamil by Meena Kandasamy November 2005 FUZZY AND NEUTROSOPHIC ANALYSIS OF PERIYAR’S VIEWS ON UNTOUCHABILITY W. B. Vasantha Kandasamy e-mail: [email protected] web: http://mat.iitm.ac.in/~wbv Florentin Smarandache e-mail: [email protected] K. Kandasamy e-mail: [email protected] Translation of the speeches and writings of Periyar from Tamil by Meena Kandasamy November 2005 2 Dedicated to Periyar CONTENTS Preface 5 Chapter One BASIC NOTION OF FCMs, FRMs, NCMs AND NRMS 1.1 Definition of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps 9 1.2 Fuzzy Cognitive Maps – Properties and Models 13 1.3 Fuzzy Relational Maps 18 1.4 An Introduction to Neutrosophy and some Neutrosophic algebraic structures 22 1.5 Neutrosophic Cognitive Maps 27 1.6 Neutrosophic Relational Maps — Definition with Examples 31 Chapter Two UNTOUCHABILITY: PERIYAR’S VIEW AND PRESENT DAY SITUATION A FUZZY AND NEUTROSOPHIC ANALYSIS 2.1 Analysis of untouchability due to Hindu religion using FCMs and NCMs 43 2.2 Analysis of discrimination faced by Dalits/ Sudras in the field of education as untouchables using FCMs and NCMs 58 2.3 Social inequality faced by Dalits and some of the most backward classes - an analysis using FCM and NCM 66 4 2.4 Problems faced by Dalits in the political arena due to discrimination – a FCM and NCM analysis 75 2.5 Study of Economic Status of Dalits due to untouchability using fuzzy and neutrosophic -

Indian Civil Service Examinations and Dalit Intervention in British India

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Indian Civil Service Examinations and Dalit Intervention in British India STALIN RAJANGAM A B RAJASEKARAN Stalin Rajangam ([email protected]) is a Dalit writer based in Madurai. A B Rajasekaran ([email protected]) is an intellectual property attorney based in Chennai. Vol. 55, Issue No. 12, 21 Mar, 2020 During the independence movement in the mid-19th century, the Paraiyar Mahajana Sabha from Tamil Nadu prevailed upon the British government to reject the demand from the Indian elite to simultaneously hold exams for the Indian Civil Services in India in addition to London. Dalit organisations at that time felt that such a move would only enable the upper- caste Indians to monopolise the bureaucracy in India. Even as the nationalist consciousness was emerging during the Indian freedom movement, there were countermovements within and outside the ambit of the freedom struggle. Their demands, especially from socially disadvantaged groups, would seem anti-national today, or at variance with the objectives of the freedom movement. But, it is essentially due to these movements that modern India is what it is today. Tamil Nadu has been a pioneer in the social justice movement, besides its contribution to the freedom struggle. Dalits were the first to form mass organisations, based on modern social justice ideas, to secure social and political rights in Tamil Nadu, as early as the second half of the 19th century (Geetha and Rajadurai 2008: 54). These ideas continue to reverberate even in the political sphere of modern-day Tamil Nadu. The Dalits perceived the ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 colonial government as a benefactor in their struggle, and found ways to secure such benefits from the colonial authorities that would eventually relieve them from the oppressive caste system. -

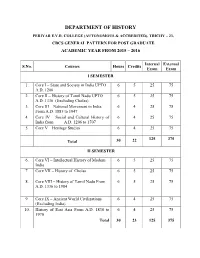

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

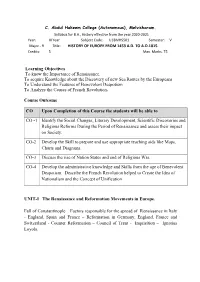

B.A., History Effective from the Year 2020-2021 Year: III Year Subject Code: U18MHS501 Semester: V Major - 9 Title: HISTORY of EUROPE from 1453 A.D

C. Abdul Hakeem College (Autonomous), Melvisharam. Syllabus for B.A., History effective from the year 2020-2021 Year: III Year Subject Code: U18MHS501 Semester: V Major - 9 Title: HISTORY OF EUROPE FROM 1453 A.D. TO A.D.1815. Credits: 5 Max. Marks. 75 Learning Objectives To know the Importance of Renaissance. To acquire Knowledge about the Discovery of new Sea Routes by the Europeans To Understand the Features of Benevolent Despotism To Analyze the Causes of French Revolution. Course Outcome CO Upon Completion of this Course the students will be able to CO -1 Identify the Social Changes, Literary Development, Scientific Discoveries and Religious Reforms During the Period of Renaissance and assess their impact on Society. CO-2 Develop the Skill to prepare and use appropriate teaching aids like Maps, Charts and Diagrams. CO-3 Discuss the rise of Nation States and end of Religious War. CO-4 Develop the administrative knowledge and Skills from the age of Benevolent Despotism. Describe the French Revolution helped to Create the Idea of Nationalism and the Concept of Unification UNIT-I The Renaissance and Reformation Movements in Europe. Fall of Constantinople – Factors responsible for the spread of Renaissance in Italy - England, Spain and France – Reformation in Germany, England, France and Switzerland - Counter Reformation – Council of Trent - Inquisition – Ignatius Loyola. C. Abdul Hakeem College (Autonomous), Melvisharam. UNIT-II Colonial Expansion in the 15th and 16th Centuries. Geographical Discoveries of Portugal and Spain - Prince Henry - Christopher Columbus - Vasco-da-Gama – Impact of the Geographical Discoveries - New scientific Inventions –Mariner’s Compass – Spinning Jenny – Gun powder. -

Technical Program

MONDAY, JULY 30 11:00AM 1801770 Polysaccharide Composites as Barrier Materials Jeffrey Catchmark, Penn State, University Park, PA TECHNICAL PROGRAM United States (Presenter: Jeffrey Catchmark) (Jeffrey MONDAY, JULY 30 Catchmark, Kai Chi, Snehasish Basu) 9:30AM-12:00PM 11:15AM 1800994 Production and characterization of in situ synthesis of silver nanoparticles into TEMPO-mediated oxi- The purpose of these Sessions is the open exchange of dized bacterial cellulose and their antivibriocidal ac- ideas, therefore, remarks made by a participant or mem- tivity against shrimp pathogens Sivaramasamy Elayaraja, Zhejiang University, ber of the audience cannot be quoted or attributed to ei- Hangzhou, Zhejiang China, People’s Republic of (Pre- ther the individual or the individuals’ company. NO senter: Sivaramasamy Elayaraja) (Sivaramasamy Ela- RECORDING of the participants’ remarks or discussion is yaraja, Liu Gang, Jianhai Xiang, Songming Zhu) 11:30AM 1801330 Design, Development, Evaluation of Gum Arabic permitted. Pictures of any material shown here are not Milling Machine permitted. Eyad Eltigani, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Khar- toum Sudan (Presenter: Eyad Eltigani) (Eyad Mohamed Eltigani Abuzeid, Khalid Elgassim Mohamed Ahmed, In respect for the presenters and the people attending the Hossamaldein Fadoul Brima) conference, ASABE would request that anyone having a 11:45AM 1801112 The Design of Longitudinal - axial cylinder for the combine pager, cell phone, or other electronic device please turn Meng Fanhu, Sandong University Technology, Zibo, them off. If your situation does not allow for these devices Shandong province China, People’s Republic of (Pre- to be turned off, please reseat yourself close to an exit senter: Meng Fanhu) (Meng Fanhu) such that everyone can benefit from the information pre- sented here without disruption. -

Master of Philosophy in History

MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY SYLLABUS - 2007-09 ST. JOSEPH’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) (Nationally Reaccredited with A+ Grade / College with Potential for Excellence) TIRUCHIRAPPALLI - 620 002 TAMIL NADU, INDIA 2 ST. JOSEPH’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), TIRUCHIRAPPALLI - 620 002 DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (M. PHIL.) FULL TIME - AUTONOMOUS REGULATIONS GUIDELINES 1. ELIGIBILITY A Candidate who has qualified for the Master’s Degree in any Faculty of this University or of any other University recognized by the University as equivalent there to (including old Regulations of any University) subject to such conditions as may be prescribed therefore shall be eligible to register for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.) and undergo the prescribed course of study in a Department concerned. A candidate who has qualified for Master’s degree (through regular study / Distance Education mode / Open University System) with not less than 55% of marks in the concerned subject in any faculty of this university or any other university recognized by Bharathidasan University, shall be eligible to register for M.Phil. SC / ST candidates are exempted by 5% from the prescribed minimum marks. 2. DURATION The duration of the M.Phil. course shall be of one year consisting of two semesters for the full-time programme. 3. COURSE OF STUDY The course of study shall consist of Part - I : 3 Written Papers Part - II : 1 Written Paper and Dissertation. The three papers under Part I shall be : Paper I : Research Methodology Paper II : Advanced / General Paper in the Subject Paper III : Advanced Paper in the subject Paper I to III shall be common to all candidates in a course. -

E:\Currently in Use\PEGASUS\IRM

IRMA GK QUESTION BANK - 2009 1. As per Vision 2020 paper by the Planning Commission of India, which of the following represents the target of the percentage population below the poverty line that government intends to achieve by the year 2020? (a) 18% (b) 15% (c) 13% (d) 10% 2. Who is the chairman of the 13th Finance Commission of India? (a) C. Rangarajan (b) Vijay L. Kelkar (c) Suresh D. Tendulkar (d) CArvind Virmani 3. As per the latest State of Forest Report, which of the following represents the percentage area covered by forests in the total geographic area of the country ? (a) 27.34% (b) 23.15% (c) 21.86% (d) 20.60% 4. This Indian state has the largest forest cover in India. Can you name it from the given options? (a) Arunachal Pradesh (b) Madhya Pradesh (c) Chhattisgarh (d) Orissa 5. As per the third advanced estimates, the production of foodgrains in 2008-2009 is expected to be … (a) 229.85 million tones (b) 224.24 million tones (c) 221.32 million tones (d) 218.45 million tones 6. Which of the following represents the per capita income in 2008-2009 measured at constant 1999- 2000 market prices? (a) Rs. 28 735 (b) Rs. 29 547 (c) Rs. 30 168 (d) Rs. 31 278 7. As per the recent Economic Survey, which of the following represents the Gross Domestic Savings as a percentage of GDP in 2007-2008 at current market prices? (a) 29.8% (b) 32.5% (c) 35.2% (d) 37.7% 8. As per the latest Economic Survey, which of the following represents the contribution of the agricul- ture sector in the national exports in 2007-2008? (a) 10.2% (b) 11.2% (c) 12.2% (d) 13.2% 9. -

Branch Libraries List

LOCAL LIBRARY AUTHORITY, KRISHNAGIRI ADDRESS LIST 1. DISTRICT CENTRAL LIBRARY, KRISHNAGIRI BANGALORE ROAD, NEAR NEW BUS STAND, KRISHNAGIRI – 635 001. BRANCH LIBRARIES 1. BRANCH LIBRARY, KAVERIPATTINAM, 2. BRANCH LIBRARY, BARGUR, KAVERIPATTINAM (POST), BARGUR (POST), KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK) – 635 112. KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK)-635 104. 3. BRANCH LIBRARY, THOGARAPALLI, 4. BRANCH LIBRARY, VEPPANAPALLI, THOGARAPALLI (POST), VEPPANAPALLI (POST), KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK)-635 203. KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK)-635 121. 5. BRANCH LIBRARY, AGARAM, 6 BRANCH LIBRARY, KATTIGANAPALLI, AGARAM(POST), KATTIGANAPALLI (POST), KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK) - 635 204. KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK) – 635 001. 7. BRANCH LIBRARY, NEDUNGAL, 8. BRANCH LIBRARY, PANAGAMUTLU, NEDUNGAL (POST), PANAGAMUTLU (POST), KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK)-635 112. KRISHNAGIRI (TALUK) – 635 106. 9. BRANCH LIBRARY, HOSUR, 10. BRANCH LIBRARY, UDDANAPALLI, HOSUR(POST), UDDANAPALLI (POST), HOSUR (TALUK) – 635 109. HOSUR(TALUK) – 635 119. 11. BRANCH LIBRARY, MATHIGIRI, 12. BRANCH LIBRARY, DENKANIKOTTA, MATHIGIRI (POST), DENKANIKOTTA (POST), HOSUR (TALUK) – 635 110 DENKANIKOTTA (TALUK) – 635 107. 13. BRANCH LIBRARY, RAYAKOTTA, 14. BRANCH LIBRARY, KELAMANGALAM, RAYAKOTTA (POST), KELAMANGALAM (POST) DENKANIKOTTA (TALUK) – 635 116. DENKANIKOTTA (TALUK) – 635 113. 15. BRANCH LIBRARY, ANCHETTY, 16. BRANCH LIBRARY, THALLY, ANCHETTY (POST), THALLY (POST), DENKANIKOTTA (TALUK) – 635 102. DENKANIKOTTA (TALUK) – 635 118. 17. BRANCH LIBRARY, URIGAM, 18. BRANCH LIBRARY, UTHANGARAI, URIGAM (POST), UTHANGARAI (POST), DENKANIKOTTA (TALUK)- 635 102. UTHANGARAI (TALUK) – 635 207. 19. BRANCH LIBRARY, KALLAVI, 20. BRANCH LIBRARY, POCHAMPALLI, KALLAVI (POST), POCHAMPALLI (POST), UTHANGARAI (TALUK) – 635 304. POCHAMPALLI (TALUK) – 635 206. 21. BRANCH LIBRARY, ARASAMPATTY, 22. BRANCH LIBRARY, MATHUR, ARASAMPATTY (POST), MATHUR (POST), POCHAMPALLI (TALUK)- 635 201. POCHAMPALLI (TALUK) – 635 203. 23. BRANCH LIBRARY, BARUR, 24. BRANCH LIBRARY, NAGARASAMPATTY, BARUR (POST), NAGARASAMPATTY (POST), POCHAMPALLI (TALUK) – 635 201. POCHAMPALLI (TALUK)- 635 204.