The Estate of Ted Russell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marlene Creates

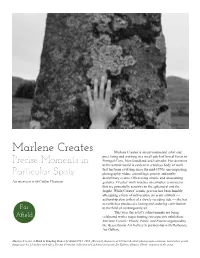

Marlene Creates Marlene Creates is an environmental artist and poet living and working in a small patch of boreal forest in Precise Moments in Portugal Cove, Newfoundland and Labrador. Her devotion to the natural world is evident in a tireless body of work that has been evolving since the mid-1970s, encompassing Particular Spots photography, video, assemblage, poetry, and multi- disciplinary events. Often using simple and unassuming An interview with Caitlin Chaisson gestures, Creates’ work touches on complex ecosystems that are powerfully sensitive to the ephemeral and the fragile. While Creates’ artistic process has been humbly attempting a form of self-erasure in recent artwork — authorship akin to that of a slowly receding tide — she has nevertheless produced a lasting and enduring contribution Far to the field of contemporary art. This year, the artist’s achievements are being Afield celebrated with a major touring retrospective exhibition: Marlene Creates: Places, Paths, and Pauses organized by the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in partnership with Dalhousie Art Gallery. Marlene Creates. A Hand to Standing Stones, Scotland 1983. 1983. [Excerpt]. Sequence of 22 black & white photographs, selenium-toned silver prints. Image size 8 x 12 inches each (20 x 30 cm). From the collection of Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa. Photo: courtesy of the artist. Caitlin Chaisson: You describe yourself as between nature and culture? an environmental artist and poet. Could you begin by MC: I think we need a dramatic shift in our culture elaborating on what this position means to you, and how — and I mean culture in the broadest sense. I don’t just you have come to use it to define your art practice? mean the arts; I mean our global consumer culture. -

Regular Public Council - Agenda Package Meeting Tuesday, January 7, 2020 Town Hall - Council Chambers, 7:00 PM

AGENDA Regular Public Council - Agenda Package Meeting Tuesday, January 7, 2020 Town Hall - Council Chambers, 7:00 PM 1. CALL OF MEETING TO ORDER 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA 3. DELEGATIONS/PRESENTATIONS - 4. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 2019 Merry and Bright Winners Thank you to Deputy Chief Eddie Sharpe 4.1 Adoption of the Regular Public Council Minutes for December 10, 2019 Regular Public Council_ Minutes - 10 Dec 2019 - Minutes (2) Draft amended 4.2 ADOPTION OF MINUTES Adoption of the Special Public Council Minutes for December 19, 2019 Special Public Council_ Minutes - 19 Dec 2019 - Minutes DRAFT 5. BUSINESS ARISING FROM MINUTES 6. COMMITTEE REPORTS PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE - Councillor Harding 1. Report Planning & Development Committee - 17 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf RECREATION & COMMUNITY SERVICES - Councillor Stewart Sharpe 1. Report Recreation/Community Services Committee - 02 Jan 2020 - Minutes - Pdf PUBLIC WORKS - Councillor Bartlett No meeting held ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, MARKETING, COMMUNICATIONS AND TOURISM - Councillor Neary 1. Report Page 1 of 139 Economic Development, Marketing, Communications, and Tourism Committee - 16 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf PROTECTIVE SERVICES - Councillor Hanlon 1. Report Protective Services Committee - 16 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE - Deputy Mayor Laham 1. Report Administration and Finance Committee - 18 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf 7. CORRESPONDENCE 7.1 Report Council Correspondence 8. NEW/GENERAL/UNFINISHED BUSINESS 8.1 2020 Schedule of Regular Council Meetings For adoption - Deputy Mayor Laham Schedule of Meetings 2020 9. AGENDA ITEMS/NOTICE OF MOTIONS ETC. 10. ADJOURNMENT Page 2 of 139 Amended DRAFT MINUTES Regular Public Council: Minutes Tuesday, December 10, 2019 Town Hall - Council Chambers, 7:00 PM Present Carol McDonald, Mayor Jeff Laham, Deputy Mayor Dave Bartlett, Councillor Johnny Hanlon, Councillor Darryl J. -

Participation in Creation and Redemption Through Placemaking and the Arts

MAKING A PLACE ON EARTH: PARTICIPATION IN CREATION AND REDEMPTION THROUGH PLACEMAKING AND THE ARTS Jennifer Allen Craft A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2013 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3732 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS ST MARY’S COLLEGE INSTITUTE FOR THEOLOGY, IMAGINATION AND THE ARTS MAKING A PLACE ON EARTH: PARTICIPATION IN CREATION AND REDEMPTION THROUGH PLACEMAKING AND THE ARTS A THESIS SUBMITTED BY: JENNIFER ALLEN CRAFT UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF TREVOR HART TO THE FACULTY OF DIVINITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ST ANDREWS, SCOTLAND MARCH 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Declarations 3 Acknowledgements and Dedication 5 Abstract 7 General Introduction 8 1 The Wide Horizons of Place: An Introduction to Place and Placemaking 16 §1: A Theological Engagement with Place and Placemaking 45 2 Placemaking in the Community of Creation: The Theological Significance of Place in Genesis 1-3 47 3 Divine and Human Placemaking in the Tabernacle and Temple: Place, Human Artistry, and Divine Presence 70 4 Making a Place on Earth: Divine Presence, Particularity, and Place in the Incarnation and its Implications for Human Participation in Creation and Redemption through Placemaking 93 Summary of Section One 125 §2: -

For Members of Mount Allison University Alumni Association

Mary Pratt ’57 Recreating the world through art Fall 2010 Mount Allison University’s Alumni and Friends No. 95 Rediscover what's important Redécouvrez ce qui importe vraiment While in New Brunswick, make a list of Pendant votre séjour au Nouveau-Brunswick, the things that are important to you. dressez la liste des choses que vous jugez That is the life you can live here. importantes. C’est ce que vous pouvez vivre ici. Be home. Make life happen. Être chez soi. Vivre comme il se doit. NBjobs.ca emploisNB.ca CNB 7172 Con tents Self-portrait, 2002, Mary Pratt Cover Story 12 Destined to paint Fea tures From a young age, renowned Canadian 16 Reimagining leadership painter Mary Pratt (’57) Michael Jones (’66) uses music to help public has been inspired by officials and industry leaders reconnect with images. She has spent the ‘personal’ and increase their productivity. her life working with light and colour to 16 18 The business of culture recreate the world Julia Chan (’08) uses her business savvy through art. to balance the books for an event promoter in Montreal. 20 A life journey John MacLachlan Gray (’68) talks about his most famous play, and how he feels Reg ulars about it more than 30 years later. 4 Events and Gatherings 22 The wedding planner 6 Campus Beat 18 Lisa Allain (’91) combines creativity and entrepreneurship to help happy couples 8 Student Spotlight plan — and pull off — the wedding of 10 Research their dreams. 27 JUMP Update 24 Home again Matthew Jocelyn (’79) heads up one of 28 Bleacher Feature Canada’s leading not-for-profit contemporary 30 In Memoriam theatre companies after achieving success in Europe. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 1 Table of Contents Vision and Mission 2 Board and Committees 3-4 From the Chair 5-6 Director’s Report 7-8 Campaign Report 9 Curatorial Report 11-12 Acquisitions & Loans 13 Exhibitions 15-17 Programs 19-21 Attendance 23 Members 25-26 Sponsors and Donors 27 Docents and Guides Bénévoles, Staff 28 Photo Credits and publications 29 1 Vision The Beaverbrook Art Gallery Enriches Life Through Art. Mission The Beaverbrook Art Gallery brings art and community together in a dynamic cultural environment dedicated to the highest standards in exhibitions, programming, education and stewardship. As the Art Gallery of New Brunswick, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery will: Maintain artistic excellence in the care, research and development of the Gallery’s widely recognized collections; Present engaging and stimulating exhibitions and programs to encourage full appreciation of the visual arts; Embrace and advance the province’s two official language communities, its First Nations Peoples and its diverse social, economic and cultural fabric; Partner to meet its goals, with the governments of New Brunswick and Canada, the general public, the private sector, cultural and educational institutions, artists and other members of the artistic community; Conduct its stewardship of the affairs of the Gallery in a financially sustainable manner; Serve as an advocate for the arts and promote art education and visual literacy; Inspire cultural self-esteem and enjoyment for all New Brunswickers. 2 Board of Governors James Irving (Chair) (E) Andrew Forestell (Secretary-Treasurer) (E) Maxwell Aitken Jeff Alpaugh Thierry Arseneau Ann Birks Earl Brewer (E) Hon. Herménégilde Chiasson, ONB Dr. -

Joan M. Schwartz, Ph.D

Joan M. Schwartz, Ph.D. Professor and Head Department of Art (Art History and Art Conservation) (cross-appointed to the Department of Geography) Queen’s University Ontario Hall 318C, 67 University Avenue, Kingston, ON, Canada K7L 3N6 (613) 533-6000 ext. 75453 [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Ph.D. (Geography), Queen's University, Kingston, ON “Agent of Sight, Site of Agency: The Photograph in the Geographical Imagination” 1977 M.A. (Geography), The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC “Images of Early British Columbia: Landscape Photography, 1858-1888” 1973 B.A. (Hons), Department of Geography, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON. “Agricultural Settlement in the Ottawa-Huron Tract, 1850-1870” EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Academic positions (2003-present) Professor and Head, Department of Art (Art History and Art Conservation; cross-appointed to Geography), Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, 2015- Associate Professor / Queen’s National Scholar, Department of Art (cross-appointed to Geography), Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, 2003-2015 (tenure granted 2009) Positions held at the National Archives of Canada, Ottawa (1977-2006) Senior Specialist, Photography Acquisition and Research, 1999-2003 (Unpaid Leave 2003-2006) Photography Preservation Specialist, Preservation Control and Circulation, 1999. Chief, Photography Acquisition and Research Section, 1986-98 (Education Leave 1996-97) Photo-Archivist, Photography Acquisition and Research, 1977-86 Previous employment (1975-1977) Policy Officer, Operations Directorate, Public Service Commission, -

A Journal of Arts & Culture

MICHAEL CRUMMEY · MARY DALTON · SPENCER GORDON · LENEA GRACE · KYM GREELEY · AUDREY HURD · BRUCE JOHNSON · ALLISON LASORDA · JANAKI LENNIE · CARMELITA MCGRATH · COLLEEN PELLATT ·JEY PETER · NED PRATT · SHEILAH ROBERTS · SUE SINCLAIR · KAREN SOLIE · JANE STEVENSON · JENNY XIE A JOURNAL OF ARTS & CULTURE No.13 No.13 A JOURNAL OF ARTS & CULTURE A JOURNAL OF ARTS & CULTURE # 13 A GENUINE NEWFOUNDLAND No. 13 — WINTER 2013 ISSN: 1913-7265 $14.95 AND LABRADOR MAGAZINE Mary Pratt, Salmon on Saran, 1974. Oil on Masonite, 45.7 x 76.2 cm. Collection of Angus and Jean Bruneau MAY 11 – SEPTEMBER 8, 2013 MARY PRATT Renowned Newfoundland and Labrador artist Mary Pratt will be celebrated in a 50-year retrospective exhibition that will open at The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery in May 2013, then tour Canada until January 2015. A project by The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, with support from the Department of Canadian Heritage, Museums Assistance Program. When you appreciate art. When you crave creativity. When you’re happiest being inspired, challenged, even surprised. There’s one place where your spirit can truly soar: The Rooms. www.therooms.ca www.therooms.ca | 709.757.8000 709.757.8000 | 9 Bonaventure | 9 Bonaventure Ave. | St. Ave.John’s, | St. NL John’s | NL FreshFiction FROM BREAKWATER Baggage JILL SOOLEY “This is honest, gripping, funny stuff.” – THE TELEGRAM Braco LESLEYANNE RYAN “A bombshell of a book… harrowing and instructive and maddening.” – MARK ANTHONY JARMAN, AUTHOR OF MY WHITE PLANET The Mean Time JAMES MATTHEWS A powerful story of how life is lived and lost between regrets. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR of the BOARD of DIRECTORS 1 OVERVIEW of the CORPORATION 2 SHARED COMMITMENTS 4 HIGHLIGHTS and ACCOMPLISHMENTS 7 PRIORITY 1 10 PRIORITY 2 14 PRIORITY 3 16 OPPORTUNITIES and CHALLENGES AHEAD 18 APPENDIX A - FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 19 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS As Chair of The Rooms Board of Directors, I am pleased to present the 2014-15 Annual Report. This report represents the outcome for the first year of the three-year planning cycle of The Rooms Strategic Plan 2014-17. The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador is a Category One entity of the Provincial Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. As such, The Rooms Annual Report 2014-15 has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Transparency and Accountability Act of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. We are pleased with The Rooms success in achieving its stated goals and objectives for this past year. The Rooms marked several significant centenaries in 2014-15 and shared them with the people of Newfoundland and Labrador. Exhibitions and public programs commemorated the 100th anniversaries of the International Grenfell Association; the Newfoundland Sealing Disasters; Rockwell Kent’s time in Brigus; and Newfoundland and Labrador’s involvement in the First World War, all were highly attended and met with resounding success. In April and May 2014, The Rooms continued its public engagement with the Corporation’s first ever travelling road show. The Rooms staff travelled to 14 communities throughout the Province with the First World War Road Show and Tell. -

Artsnews SERVING the ARTS in the FREDERICTON REGION

ARTSnews SERVING THE ARTS IN THE FREDERICTON REGION July 9, 2015 Volume 16, Issue 27 In this issue *Click the “Back to top” link after each notice to return to “In This Issue”. Upcoming Events 1. The Fredericton Arts Alliance Artist in Residence Program 2015 2. Calithumpians Haunted Hikes and Theatre-in-the-Park Jul 2-Sep 5 3. Gallery 78 presents New Works by Karen Burk, Lee Horus Clark, and Yolande Clark 4. Hannah’s Tea Place is Becoming a Family Affair 5. Penny’s Flic Pic: The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out The Window And Disappeared Jul 9 6. Upcoming Fredericton Tourism Events Jul 9-15 7. House Concert With Ron Hynes Jul 11 8. Battle of the Arts New Brunswick 2015 Auditions Jul 11 9. Fredericton Botanic Garden Association presents the Annual Treasured Garden Tour Jul 12 10. The Capital and Centre communautaire Sainte-Anne present Sweet Crude Aug 13 11. Strawberries and Champagne Social featuring Sally Dibblee Jul 14 12. Coming up at the Fredericton Playhouse Jul 14-22 13. Cineplex’s National Theatre Live presents Everyman Jul 16 14. Rob Currie at the Charlotte Street Arts Centre Jul 17 15. FredRock Music Festival Jul 17-18 16. Battle of the Comedians at The Delta Fredericton Jul 18 17. Warrior Sun Tour featuring Joey Stylez, Winnipeg Boyz and Special Guests Jul 19 18. Diane London Award Presented To Local Musician 19. Beaverbrook Art Gallery to Launch The Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation Art Critic Residency Program Workshops | Classes | Art Camps 1. Go Go Go Joseph Summer Camp at the Black Box Theatre 2. -

Annual Report 2018/19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 TABLE OF CONTENTS A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR of the BOARD of DIRECTORS 1 OVERVIEW of the CORPORATION 3 HIGHLIGHTS and ACCOMPLISHMENTS 5 PARTNERSHIPS 9 PRIORITY 1 13 PRIORITY 2 23 PRIORITY 3 31 OPPORTUNITIES and CHALLENGES AHEAD 34 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 35 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS This past year was my second year serving as Chair of The Rooms Board of Directors. This year also marked the completion of the second year of The Rooms Corporation’s 2017-20 Strategic Plan. This plan is built on the goals and priorities The Rooms has identified over the past 14 years and sets the strategic priorities for the current planning cycle. The plan focuses on building strong connections with visitors, members and the people of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Rooms made several achievements during the past year, advancing the Corporation’s strategic priorities. These achievements are in alignment with the Provincial Government’s The Way Forward and in particular the 2017-20 Provincial Tourism Product Development Plan. The Rooms continues to develop and offer visitors engaging, immersive, people and program-based experiences. Enhanced experiences include programs and exhibitions that represented defining aspects of Newfoundland and Labrador’s unique culture, including Indigenous tourism experiences. As part of the Provincial Government’s plan to deliver enhanced programs and experiences, The Rooms has extended its non-resident programming into the Fall – providing shoulder season tourism experience offerings. Margaret E. Allan Chair, Board of Directors, The Rooms will continue to work on the 2017-20 Provincial The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador Development Plan areas of focus during the third and final year of its 2017-20 strategic planning cycle. -

PA HALL Prayer Is the Study of Art

W HIPPIN THE T PA HALL Prayer is the study of art. Praise is the practice of art. - William Blake, The Laocoon Callanish Stones - Main Circle I was stone, mysterious stone; my breach was a violent one, my birth like a wounding estrangement, but now I should like to return to that certainty, to the peace of the center, the matrix of mothering. stone. - Pablo Neruda, SkystonesXX/II cover: The Wounded Cross MEMORIALUNIVERSITY ART GALLERY ST. JOHN'S NEWFOUNDLAND1987 INTRODUCTION Pam Hall's intention, in her Worshipping the Stone series, is to make monuments - in a time and society in which we seem to believe we need none . In making these works she draws not only on her own skills and imagination but on a personal enduring response to the earliest monuments we know. the great prehistoric stone sites such as Comae in Brittany, Avebury, Dartmoor, and , in particu lar Callanish in Scotland . Hall shares with many artists this reference to prehistory, this working from forms of the past to g ive meaning to the present. American art historian Lucy Lippard has described anc ient sites, symbols and artifacts as a major source of Ideas for American artists of the past two decades . She sees this in part as breaking away from a reductive art focused on purely formal elements and. in larger part , as an effort to restore to art a function beyond decoration, to give it an integral role in daily life as a link between humans and their environment, a concrete expression of some general human experience .1 Such contemporary art is extremely diverse, ranging from ritualistic performance pieces and body works such as those of Ana Mendieta , through sculpture, to giant-scale earthworks by artists like Dennis Oppenheim and Robert Smithson. -

Sample Chapter

6 courtesy Parks canada St. John’s Most people don’t come to Newfoundland for city life, but once in the province they invariably rave about St. John’s. The city is responsible for a good part of the province’s economic output, and is home to Memorial University. The 2006 census has the city population at a modest 100,000, but the metro area count is 180,000 and fast-growing. St. John’s is a region unto itself. It was the capital of the Dominion of Newfoundland and Labrador prior to Confederation with Canada in 1949. As such, it retains elements (and attitudes) of a national capital and is, of course, the provincial capital. St. John’s claim to be the oldest European- settled city in North America is contested, however, it is clear that it was an important fishing port in the early 1500s and received its first permanent settlers in the early 1600s. Moreover, there is no doubt that Water Street is the oldest commercial street in North America. Formerly known as the lower path, it was the route by which fishermen, servants, and traders (along with pirates and naval officers) moved from storehouse, to ware- house to alehouse. They did so in order to purchase or barter the supplies necessary to secure a successful voyage at the Newfoundland fishery. Centuries later, the decline of the fishery negatively affected St. John’s, but oil and gas discoveries, and a rising service sector, have boosted the city’s fortunes. For visitors, St. John’s memorably hilly streets, fascinating architecture, and spectacular harbour and cliffs make it the perfect place 7 to begin (or end) a trip to Newfoundland.