Participation in Creation and Redemption Through Placemaking and the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marlene Creates

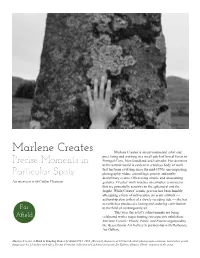

Marlene Creates Marlene Creates is an environmental artist and poet living and working in a small patch of boreal forest in Precise Moments in Portugal Cove, Newfoundland and Labrador. Her devotion to the natural world is evident in a tireless body of work that has been evolving since the mid-1970s, encompassing Particular Spots photography, video, assemblage, poetry, and multi- disciplinary events. Often using simple and unassuming An interview with Caitlin Chaisson gestures, Creates’ work touches on complex ecosystems that are powerfully sensitive to the ephemeral and the fragile. While Creates’ artistic process has been humbly attempting a form of self-erasure in recent artwork — authorship akin to that of a slowly receding tide — she has nevertheless produced a lasting and enduring contribution Far to the field of contemporary art. This year, the artist’s achievements are being Afield celebrated with a major touring retrospective exhibition: Marlene Creates: Places, Paths, and Pauses organized by the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in partnership with Dalhousie Art Gallery. Marlene Creates. A Hand to Standing Stones, Scotland 1983. 1983. [Excerpt]. Sequence of 22 black & white photographs, selenium-toned silver prints. Image size 8 x 12 inches each (20 x 30 cm). From the collection of Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa. Photo: courtesy of the artist. Caitlin Chaisson: You describe yourself as between nature and culture? an environmental artist and poet. Could you begin by MC: I think we need a dramatic shift in our culture elaborating on what this position means to you, and how — and I mean culture in the broadest sense. I don’t just you have come to use it to define your art practice? mean the arts; I mean our global consumer culture. -

Regular Public Council - Agenda Package Meeting Tuesday, January 7, 2020 Town Hall - Council Chambers, 7:00 PM

AGENDA Regular Public Council - Agenda Package Meeting Tuesday, January 7, 2020 Town Hall - Council Chambers, 7:00 PM 1. CALL OF MEETING TO ORDER 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA 3. DELEGATIONS/PRESENTATIONS - 4. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 2019 Merry and Bright Winners Thank you to Deputy Chief Eddie Sharpe 4.1 Adoption of the Regular Public Council Minutes for December 10, 2019 Regular Public Council_ Minutes - 10 Dec 2019 - Minutes (2) Draft amended 4.2 ADOPTION OF MINUTES Adoption of the Special Public Council Minutes for December 19, 2019 Special Public Council_ Minutes - 19 Dec 2019 - Minutes DRAFT 5. BUSINESS ARISING FROM MINUTES 6. COMMITTEE REPORTS PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE - Councillor Harding 1. Report Planning & Development Committee - 17 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf RECREATION & COMMUNITY SERVICES - Councillor Stewart Sharpe 1. Report Recreation/Community Services Committee - 02 Jan 2020 - Minutes - Pdf PUBLIC WORKS - Councillor Bartlett No meeting held ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, MARKETING, COMMUNICATIONS AND TOURISM - Councillor Neary 1. Report Page 1 of 139 Economic Development, Marketing, Communications, and Tourism Committee - 16 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf PROTECTIVE SERVICES - Councillor Hanlon 1. Report Protective Services Committee - 16 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE - Deputy Mayor Laham 1. Report Administration and Finance Committee - 18 Dec 2019 - Minutes - Pdf 7. CORRESPONDENCE 7.1 Report Council Correspondence 8. NEW/GENERAL/UNFINISHED BUSINESS 8.1 2020 Schedule of Regular Council Meetings For adoption - Deputy Mayor Laham Schedule of Meetings 2020 9. AGENDA ITEMS/NOTICE OF MOTIONS ETC. 10. ADJOURNMENT Page 2 of 139 Amended DRAFT MINUTES Regular Public Council: Minutes Tuesday, December 10, 2019 Town Hall - Council Chambers, 7:00 PM Present Carol McDonald, Mayor Jeff Laham, Deputy Mayor Dave Bartlett, Councillor Johnny Hanlon, Councillor Darryl J. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 1 Table of Contents Vision and Mission 2 Board and Committees 3-4 From the Chair 5-6 Director’s Report 7-8 Campaign Report 9 Curatorial Report 11-12 Acquisitions & Loans 13 Exhibitions 15-17 Programs 19-21 Attendance 23 Members 25-26 Sponsors and Donors 27 Docents and Guides Bénévoles, Staff 28 Photo Credits and publications 29 1 Vision The Beaverbrook Art Gallery Enriches Life Through Art. Mission The Beaverbrook Art Gallery brings art and community together in a dynamic cultural environment dedicated to the highest standards in exhibitions, programming, education and stewardship. As the Art Gallery of New Brunswick, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery will: Maintain artistic excellence in the care, research and development of the Gallery’s widely recognized collections; Present engaging and stimulating exhibitions and programs to encourage full appreciation of the visual arts; Embrace and advance the province’s two official language communities, its First Nations Peoples and its diverse social, economic and cultural fabric; Partner to meet its goals, with the governments of New Brunswick and Canada, the general public, the private sector, cultural and educational institutions, artists and other members of the artistic community; Conduct its stewardship of the affairs of the Gallery in a financially sustainable manner; Serve as an advocate for the arts and promote art education and visual literacy; Inspire cultural self-esteem and enjoyment for all New Brunswickers. 2 Board of Governors James Irving (Chair) (E) Andrew Forestell (Secretary-Treasurer) (E) Maxwell Aitken Jeff Alpaugh Thierry Arseneau Ann Birks Earl Brewer (E) Hon. Herménégilde Chiasson, ONB Dr. -

Curators' Choice on Art and Politics

Curators’ Choice on Art and Politics Experts from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, choose their favorite works with a political message. By Ted Loos March 9, 2020 “Vote Quilt” (1975) by Irene Williams Pamela Parmal, chair of textile and fashion arts Quilts such as this example by Irene Williams of Gee’s Bend, Ala., are a reminder of how women, primarily restricted to the domestic sphere, have often turned to needlework to express themselves. We can only speculate that in using the VOTE fabric, Irene Williams might be recalling her community’s struggle over voting rights during the tumultuous civil rights movement of the 1960s. But as Williams understood, it is only by making our voices heard that we can move toward greater understanding and create change. Hanging trees and hollering ghosts: the unsettling art of the American deep south The porch of artist Emmer Sewell. Photograph: © Hannah Collins From lynching and slavery to the civil rights movement, Alabama’s artists expressed the momentous events they lived through – as a landmark new exhibition reveals Lanre Bakare Wed 5 Feb 2020 The quilters of Gee’s Bend make art out of recycled cloth. Lonnie Holley crafts sculptures out of car tyres and other human detritus. Self-taught luthier Freeman Vines carves guitars out of wood that came from a “hanging tree” once used to lynch black men. The “yard shows” of Dinah Young and Joe Minter are permanent exhibitions of their art – a cacophony of “scrap-iron elegies”. Almost all of this art comes from Alabama, and it all features in We Will Walk, Turner Contemporary’s groundbreaking new exhibition of African-American art from the southern state and its surroundings. -

Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art

C In 1927, the Chicago Art Institute presented the first major museum exhibition of OOKS art by African Americans. Designed to demonstrate the artists’ abilities and to promote racial equality, the exhibition also revealed the art world’s anxieties about the participa- EXHIBITING tion of African Americans in the exclusive venue of art museums—places where blacks had historically been barred from visiting let alone exhibiting. Since then, America’s major art museums have served as crucial locations for African Americans to protest against their exclusion and attest to their contributions in the visual arts. BLACKNESS In Exhibiting Blackness, art historian Bridget R. Cooks analyzes the curatorial strate- AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE AMERICAN ART MUSEUM gies, challenges, and critical receptions of the most significant museum exhibitions of African American art. Tracing two dominant methodologies used to exhibit art by African Americans—an ethnographic approach that focuses more on artists than their art, and a EXHIBITING recovery narrative aimed at correcting past omissions—Cooks exposes the issues involved in exhibiting cultural difference that continue to challenge art history, historiography, and American museum exhibition practices. By further examining the unequal and often con- tested relationship between African American artists, curators, and visitors, she provides insight into the complex role of art museums and their accountability to the cultures they represent. “An important and original contribution to the study of the history -

Joan M. Schwartz, Ph.D

Joan M. Schwartz, Ph.D. Professor and Head Department of Art (Art History and Art Conservation) (cross-appointed to the Department of Geography) Queen’s University Ontario Hall 318C, 67 University Avenue, Kingston, ON, Canada K7L 3N6 (613) 533-6000 ext. 75453 [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Ph.D. (Geography), Queen's University, Kingston, ON “Agent of Sight, Site of Agency: The Photograph in the Geographical Imagination” 1977 M.A. (Geography), The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC “Images of Early British Columbia: Landscape Photography, 1858-1888” 1973 B.A. (Hons), Department of Geography, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON. “Agricultural Settlement in the Ottawa-Huron Tract, 1850-1870” EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Academic positions (2003-present) Professor and Head, Department of Art (Art History and Art Conservation; cross-appointed to Geography), Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, 2015- Associate Professor / Queen’s National Scholar, Department of Art (cross-appointed to Geography), Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, 2003-2015 (tenure granted 2009) Positions held at the National Archives of Canada, Ottawa (1977-2006) Senior Specialist, Photography Acquisition and Research, 1999-2003 (Unpaid Leave 2003-2006) Photography Preservation Specialist, Preservation Control and Circulation, 1999. Chief, Photography Acquisition and Research Section, 1986-98 (Education Leave 1996-97) Photo-Archivist, Photography Acquisition and Research, 1977-86 Previous employment (1975-1977) Policy Officer, Operations Directorate, Public Service Commission, -

At the Met, a Riveting Testament to Those Once Neglected

JAMES FUENTES 55 Delancey Street New York, NY 10002 (212) 577-1201 [email protected] ART REVIEW At the Met, a Riveting Testament to Those Once Neglected History Refused to Die NYT Critic's Pick By Roberta Smith May 24, 2018 Thornton Dial’s two-sided relief-painting-assemblage, “History Refused to Die” (2004), also gives this Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition its title. His work is in conversation with quilts by, from left, Linda Pettway (“Housetop,” circa 1975); Lucy T. Pettway (“Housetop” and “Bricklayer” blocks with bars, circa 1955); and Annie Mae Young (“Work-clothes quilt with center medallion of strips,” from 1976).Credit2018 Estate of Thornton Dial/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Agaton Strom for The New York Times JAMES FUENTES American art from the 20th and 21st centuries is broader, and better than previously acknowledged, especially by museums. As these institutions struggle to become more inclusive than before, and give new prominence to neglected works, they rarely act alone. Essential help has come from people like William Arnett and his exemplary Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Their focus is the important achievement of black self-taught artists of the American South, born of extreme deprivation and social cruelty, raw talent and fragments of lost African cultures. The foundation is in the process of dispersing the entirety of its considerable holdings — some 1,200 works by more than 160 artists — to museums across the country. When it is finished, it may well have an impact not unlike that of the Kress Foundation, which from 1927 to 1961 gave more than 3,000 artworks to 90 museums and study collections. -

The Estate of Ted Russell

“... I think there is merit in just ’being.’ Somehow or other the greatest gift we have is the gift of our own consciousness, and that is worth savouring. Just to be in a place that’s so silent that you can hear the blood going through your arteries and be aware of your own existence, that you are matter that knows it is matter, and that this is the ultimate miracle.” – Christopher Pratt, artist 584 This painting entitled We Filled ‘Em To The Gunnells by Sheila Hollander shows what life possibly may have been like in XXX circa XXX. Fig. 3.4 Artist profiles 585 Artist profile Fig. 1 Angela Andrew Angela Andrew – Tea Doll Designer Innu tea dolls have been created by Nitassinan Innu of Quebec and Labrador for over a hundred years. (The earliest collected examples of tea dolls date back to the 1880s.) But today, Angela Andrew of Sheshatshiu is one of the few craftspeople keeping the tradition alive. She makes as many as 100 tea dolls a year – many of which are sold to art collectors. Angela learned the art of making tea dolls from Maggie Antoine, a woman from her father’s community of Davis Inlet. She learned her sewing skills from her parents, who originally lived a life of hunting and trapping in the bush. Angela played with tea dolls as a child. She explains that when her family travelled across Labrador, following the caribou and other game, everyone in the family helped pack and carry their belongings ‑ even the smallest children. Because of this, older women made dolls for the little girls and stuffed them with as much as a kilogram (two pounds) of loose tea leaves. -

Black Stitches: African American Women's Quilting and Story Telling

Luisa Cazorla Torrado DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Black Stitches: African American Women‘s Quilting and Story Telling Supervised by Dr. Belén Martín Lucas 2020 International Doctoral School Belén Martín Lucas DECLARES that the present work, entitled ―Black Stitches: African American Women‘s Quilting and Story Telling‖, submitted by Luisa Cazorla Torrado to obtain the title of Doctor, was carried out under her supervision in the PhD programme ―Interuniversity Doctoral Programme in Advanced English Studies.‖ This is a joint PhD programme integrating the Universities of Santiago de Compostela (USC), A Coruña (UDC), and Vigo (UVigo). Vigo, September 1, 2020. The supervisor, Dr. Belén Martín Lucas Acknowledgements I would like to say thanks: To my mother, M. Carmen, for encouraging me to keep sewing every day, no matter what; to my sister, María, for always bringing new light whenever my eyes were getting weary; to my friend, Belén, for showing me how to adjust the quilt frame; to my supervisor, Belén, for helping me find a better thread and for teaching me how to improve my stitches; and to my sons, Alejandro and Daniel, for reminding me of the ―big pattern‖ whenever I would forget the reasons why I was sewing this quilt. I couldn‘t have done this without your sustained encouragement and support during all these years. Table of contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................... 4 Table of contents ............................................................................. 5 Resumo ........................................................................................... -

Apprenticeship Program

Celebrating Twenty Years of the Alabama Folk Arts Apprenticeship Program Alabama State Council on the Arts Photography by Mark Gooch 20 Alabama Center for Traditional Culture Carry On Celebrating Twenty Years of the Alabama Folk Arts Apprenticeship Program Alabama State Council on the Arts 20Alabama Center for Traditional Culture Photography by Mark Gooch S © 2008 Alabama State Council on the Arts The Mission of the Alabama State Council on the Arts is to enhance quality of life in Alabama culturally, economically, and educationally by supporting the state’s diverse and rich artistic resources. The Alabama Center for Traditional Culture, a division of the Alabama State Council on the Arts, strives to document, preserve and present Alabama’s folk culture and traditional arts and to further the understanding of our cultural heritage. Alabama State Council on the Arts 201 Monroe Street, Suite 110 Montgomery, AL 36130 334-242-4076 www.arts.alabama.gov Front cover photo: Matt Downer and his grandfather, Wayne Heard of Ider. Back cover photo: Sylvia Stephens, Ashlee Harris, and Mozell Benson; three generations of quilters at Mrs. Benson’s studio in Waverly. Introduction Carry On: Celebrating Twenty Years of Alabama’s Folk Arts Apprenticeship Program By Joey Brackner and Anne Kimzey ince 1984, the Alabama State Council on the Arts (ASCA) has awarded Folk Arts S Apprenticeship grants to more than 100 master folk artists for teaching their art forms. The master-apprentice system is a time-honored method for teaching complex skills from one generation to the Prospective students who have entered into next. This process allows for the most advantageous an agreement with a master folk artist have teacher-student ratio and fosters serious instruction. -

The Gee's Bend Quilt Mural Trail

A History of Gee’s Bend GEE’S BEND is surrounded on three sides by water. This The Gee’s Bend water is a large bend in the Quilt Mural Alabama River. The community Trail is collectively known as Gee’s Bend but has been renamed Top Row Top Row Top Row Top Row Top Row Boykin. This area Mary Lee Bendolph Minnie Sue Ruthy Mosely Lottie Mooney Loretta Pettway was founded by Born 1935 Coleman Born 1926 1908-1992 Born 1942 the Gee family in “Housetop” Born 1926 “Nine Patch” “Housetop– Four- “Roman Stripes” variation “Pig in a Pen” Blocks. Half-Log variation or Crazy the early 1800’s. medallion Cabin” variation Quilt The Gee family sold the land to Bottom Row Bottom Row Bottom Row Bottom Row Bottom Row Alonzia Pettway Annie Mae Young Loretta Pettway Jessie T. Pettway Patty Ann Williams Mark Pettway in Born 1923 Born 1928 Born 1942 Born 1929 1898-1972 1845. “Chinese Coins” “Blocks And “Medallion” “Bars and String- “Medallion with variation Stripes” Pieced Columns” checker board center” ALA-TOM RC&D Selma Post Office Box 355 • 16 West Front Street South WILCOX Alabama’s Front Porches: Thomasville Thomasville, Alabama 36784 Phone (334) 636-0120 Fax (334) 636-0122 famous for great Southern food, Established in November 2008. hospitality and architecture, Gee’s Bend Quilt Collective beautiful pastoral landscapes, Directions: From Location: N32°10’26.5”W087°21’42.2” a rich cultural and agricultural Ms. Mary Ann Pettway (334) 682-2535 Montgomery, go west on US heritage, outdoor recreation 80 to Selma. -

PA HALL Prayer Is the Study of Art

W HIPPIN THE T PA HALL Prayer is the study of art. Praise is the practice of art. - William Blake, The Laocoon Callanish Stones - Main Circle I was stone, mysterious stone; my breach was a violent one, my birth like a wounding estrangement, but now I should like to return to that certainty, to the peace of the center, the matrix of mothering. stone. - Pablo Neruda, SkystonesXX/II cover: The Wounded Cross MEMORIALUNIVERSITY ART GALLERY ST. JOHN'S NEWFOUNDLAND1987 INTRODUCTION Pam Hall's intention, in her Worshipping the Stone series, is to make monuments - in a time and society in which we seem to believe we need none . In making these works she draws not only on her own skills and imagination but on a personal enduring response to the earliest monuments we know. the great prehistoric stone sites such as Comae in Brittany, Avebury, Dartmoor, and , in particu lar Callanish in Scotland . Hall shares with many artists this reference to prehistory, this working from forms of the past to g ive meaning to the present. American art historian Lucy Lippard has described anc ient sites, symbols and artifacts as a major source of Ideas for American artists of the past two decades . She sees this in part as breaking away from a reductive art focused on purely formal elements and. in larger part , as an effort to restore to art a function beyond decoration, to give it an integral role in daily life as a link between humans and their environment, a concrete expression of some general human experience .1 Such contemporary art is extremely diverse, ranging from ritualistic performance pieces and body works such as those of Ana Mendieta , through sculpture, to giant-scale earthworks by artists like Dennis Oppenheim and Robert Smithson.