An Initiative for the Rehabilitation Ita Wegman Elisabeth Vreede

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harry Collison, MA – Kingston University Working Paper ______

Harry Collison, MA – Kingston University Working Paper __________________________________________________________________________________________ HARRY COLLISON, MA (1868-1945): Soldier, Barrister, Artist, Freemason, Liveryman, Translator and Anthroposophist Sir James Stubbs, when answering a question in 1995 about Harry Collison, whom he had known personally, described him as a dilettante. By this he did not mean someone who took a casual interest in subjects, the modern usage of the term, but someone who enjoys the arts and takes them seriously, its more traditional use. This was certainly true of Collison, who studied art professionally and was an accomplished portraitist and painter of landscapes, but he never had to rely on art for his livelihood. Moreover, he had come to art after periods in the militia and as a barrister and he had once had ambitions of becoming a diplomat. This is his story.1 Collisons in Norfolk, London and South Africa Originally from the area around Tittleshall in Norfolk, where they had evangelical leanings, the Collison family had a pedigree dating back to at least the fourteenth century. They had been merchants in the City of London since the later years of the eighteenth century, latterly as linen drapers. Nicholas Cobb Collison (1758-1841), Harry’s grandfather, appeared as a witness in a case at the Old Bailey in 1800, after the theft of material from his shop at 57 Gracechurch Street. Francis (1795-1876) and John (1790-1863), two of the children of Nicholas and his wife, Elizabeth, née Stoughton (1764-1847), went to the Cape Colony in 1815 and became noted wine producers.2 Francis Collison received the prize for the best brandy at the first Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society competition in 1833 and, for many years afterwards, Collison was a well- known name in the brandy industry. -

Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 4/18

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 4/18 ■ Anthroposophical Society April 2018 • N° 4 Anthroposophical Society 2018 Annual Conference and agm The Executive Council at the Goetheanum after the motion to reaffirm 1 Executive Council letter to members Paul Mackay and Bodo von Plato was rejected 2 agm minutes 6 Reflections 8 Reports General Anthroposophical Society 10 Address by Paul Mackay Address by Bodo von Plato Statement from the Executive 11 Outcome of ballot Seija Zimmermann: emerita status Council at the Goetheanum 12 Elisabeth Vreede, Ita Wegman The agenda of this year’s Annual General Meeting of the General Anthroposophical 18 Obituary: Vladimir Tichomirov Society included a motion to reaffirm Paul Mackay and Bodo von Plato as Executive Obituary: Lyda Bräunlich Council members. The majority of members present rejected this motion. The Execu- 19 Obituary: Johannes Zwiauer tive Council at the Goetheanum has responded with a letter to the members. Membership news School of Spiritual Science Dear members of the Plato since 2001. After an extensive and con- 13 General Anthroposophical Section: Anthroposophical Society, troversial debate at the agm the proposal Goetheanum Studies was rejected by the majority of members 14 Medical Section: We acknowledge with sadness that the present. We have to accept this decision. Research congress motion we submitted, and which was sup- In addition, a number of general secretar- Anthroposophic Medicine ported by the Goetheanum Leadership and ies pointed out that many members who Anthroposophy Worldwide the Conference of General Secretaries, to live at a greater distance from the Goethea- 15 Germany: Congress on vaccination extend the term of office of Paul Mackay num are excluded from having their say in 15 Germany: Rheumatoid and Bodo von Plato as members of the Ex- these situations because they are unable Arthritis study ecutive Council was rejected by the agm to attend for financial reasons. -

Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 12/17

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 12/17 ■ Anthroposophical Society Preliminary invitation to the 2018 December 2017 • N° 12 Annual Members’ Conference at the Goetheanum Anthroposophical Society What do we build on? 1 2018 Annual Members’ Meetings «What do we build on?» will be the motif of a conference to which the Executive Coun- 3 2017 Christmas Appeal cil and Goetheanum Leadership would like to warmly invite all members. The confer- 16 Christmas Community and ence will form part of the Annual Meeting and agm at the Goetheanum from 22 to 25 General Anthroposophical March 2018. Issues discussed will include future perspectives of the Anthroposophical Society Colloquium Society and a new approach to this annual gathering of members. 18 General Secretaries Conference 19 Italy: Youth Conference Seeking We would like to call your attention at this Our-Selves early date to the Members’ Conference 20 Footnotes to Ein Nachrichtenblatt which will be held just before Easter 2018. 20 Newssheets: ‹being human› As part of the development the Goethea- 24 Obituary: Hélène Oppert num is undergoing at present, the Annual 23 Membership News Conference as we know it and the agm, which is included in the Annual Conference, Goetheanum are also intended to be further developed 4 The Goetheanum in Development and newly designed. Discussions will fo- 5 Communication cus on future perspectives for the Anthro- 5 The Goetheanum Stage posophical Society and the continuation of the Goetheanum World Conference at School of Spiritual Science Michaelmas 2016. We would like to pres- 6 Youth Section ent the 2018 Members’ Conference as an 7 Natural Science Section event where members come together in The Members’ Conference: a place for 8 Humanities Section dialogue and conversation and rejoice in meetings and conversations (2016 9 Pedagogical Section meeting one another. -

The Pioneers of Biodynamics in USA: the Early Milestones of Organic Agriculture in the United States

American Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development Vol. 6, No. 2, 2019, pp. 89-94 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/ajesd The Pioneers of Biodynamics in USA: The Early Milestones of Organic Agriculture in the United States John Paull * Environment, Resources & Sustainability, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia Abstract Biodynamics has played a key role in environmental and sustainable development. Rudolf Steiner founded the Experimental Circle of Anthroposophic Farmers and Gardeners at Koberwitz (now Kobierzyce, Poland) in 1924. The task for the Experimental Circle was to test Steiner’s ‘hints’ for a new and sustainable agriculture, to find out what works, and to publish and tell the world. Ehrenfried published his book Bio-Dynamic Farming and Gardening in New York in 1938, fulfilling Steiner’s directive. In the interval, 1924-1938, 39 individual Americans joined the Experimental Circle . They were the pioneers of biodynamics and organics in USA, and finally their names and locations are revealed. Of the 39 members, three received copies of the Agriculture Course in both German and English, while other copies were shared (n=6). Of the 35 Agriculture Courses supplied to American Experimental Circle Members, over half were numbered copies of the German edition (n=20), and the rest were the English edition (n=15). A majority of members were women (n=20), along with men (n=17), and undetermined (n=2). Members were from 11 states: New York (n=18), New Jersey (n=5), Ohio (n=4), Hawaii (n=3), Connecticut (n=2), Missouri (n=2), California (n=1), Florida (n=1), Maine (n=1), Maryland (n=1), and Pennsylvania (n=1). -

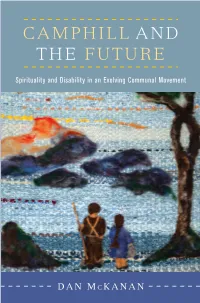

Camphill and the Future

DISABILITY STUDIES | RELIGION M C KANAN THE CAMPHILL MOVEMENT, one of the world’s largest and most enduring networks of intentional communities, deserves both recognition and study. CAMPHILL A ND Founded in Scotland at the beginning of the Second World War, Camphill communities still thrive today, encompassing thousands of people living in more CAMPHILL than one hundred twenty schools, villages, and urban neighborhoods on four continents. Camphillers of all abilities share daily work, family life, and festive THE FUTURE celebrations with one another and their neighbors. Unlike movements that reject mainstream society, Camphill expressly seeks to be “a seed of social renewal” by evolving along with society to promote the full inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities, who comprise nearly half of their residents. In this Spirituality and Disability in an Evolving Communal Movement multifaceted exploration of Camphill, Dan McKanan traces the complexities of AND THE the movement’s history, envisions its possible future, and invites ongoing dia- logue between the fields of disability studies and communal studies. “Dan McKanan knows Camphill better than anyone else in the academic world FUTURE and has crafted an absorbing account of the movement as it faces challenges eighty years after its founding.” TIMOTHY MILLER, author of The Encyclopedic Guide to American Inten- tional Communities “This book serves as a living, working document for the Camphill movement. Spirituality and Disability Communal Movement in an Evolving McKanan shows that disability studies and communal studies have more to offer each other than we recognize.” ELIZABETH SANDERS, Managing Director, Camphill Academy “With good research and wonderful empathy, McKanan pinpoints not only Cam- phill’s societal significance but also how this eighty-year-old movement can still bring potent remediation for the values and social norms of today’s world.” RICHARD STEEL, CEO, Karl König Institute DAN MCKANAN is the Emerson Senior Lecturer at Harvard Divinity School. -

The Library of Rudolf Steiner: the Books in English Paull, John

www.ssoar.info The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English Paull, John Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Paull, J. (2018). The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English. Journal of Social and Development Sciences, 9(3), 21-46. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-59648-1 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Journal of Social and Development Sciences (ISSN 2221-1152) Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 21-46, September 2018 The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English John Paull School of Technology, Environments and Design, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: The New Age philosopher, Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), was the most prolific and arguably the most influential philosopher of his era. He assembled a substantial library, of approximately 9,000 items, which has been preserved intact since his death. Most of Rudolf Steiner’s books are in German, his native language however there are books in other languages, including English, French, Italian, Swedish, Sanskrit and Latin. There are more books in English than in any other foreign language. Steiner esteemed English as “a universal world language”. The present paper identifies 327 books in English in Rudolf Steiner’s personal library. -

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 4/18

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 4/18 ■ ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY April 2018 • N° 4 Anthroposophical Society 2018 Annual Conference and AGM The Executive Council at the Goetheanum after the motion to reaffirm 1 Executive Council letter to members Paul Mackay and Bodo von Plato was rejected 2 AGM minutes 6 Reflections 8 Reports General Anthroposophical Society 10 Address by Paul Mackay Address by Bodo von Plato Statement from the Executive 11 Outcome of ballot Seija Zimmermann: emerita status Council at the Goetheanum 12 Elisabeth Vreede, Ita Wegman The agenda of this year’s Annual General Meeting of the General Anthroposophical 18 Obituary: Vladimir Tichomirov Society included a motion to reaffirm Paul Mackay and Bodo von Plato as Executive Obituary: Lyda Bräunlich Council members. The majority of members present rejected this motion. The Execu- 19 Obituary: Johannes Zwiauer tive Council at the Goetheanum has responded with a letter to the members. Membership news School of Spiritual Science Dear members of the Plato since 2001. After an extensive and con- 13 General Anthroposophical Section: Anthroposophical Society, troversial debate at the AGM the proposal Goetheanum Studies was rejected by the majority of members 14 Medical Section: We acknowledge with sadness that the present. We have to accept this decision. Research congress motion we submitted, and which was sup- In addition, a number of general secretar- Anthroposophic Medicine ported by the Goetheanum Leadership and ies pointed out that many members who Anthroposophy Worldwide the Conference of General Secretaries, to live at a greater distance from the Goethea- 15 Germany: Congress on vaccination extend the term of office of Paul Mackay num are excluded from having their say in 15 Germany: Rheumatoid and Bodo von Plato as members of the Ex- these situations because they are unable Arthritis study ecutive Council was rejected by the AGM to attend for financial reasons. -

Impulse Aus Den Elementen Die Initiative ›Summer School Iona and Isle of Mull‹

74 Feuilleton Renatus Derbidge Impulse aus den Elementen Die Initiative ›Summer School Iona and Isle of Mull‹ Es begann mit einer Intuition, vor Ort, bei sie seelisch beobachtend und meditativ erwei- einem Besuch der west-schottischen Insel Iona ternd. Innerlich erlebten die Beteiligten die vor einigen Jahren: Hier muss anthroposo- Tage als initiatorischen Prozess, der ihnen Welt phisch etwas passieren! Bald entwickelte sich und Selbst näher brachte. 2017 gelang es, dies der Gedanke weiter. Was passt zu diesem Ort? noch zu intensivieren, durch kleinere Arbeits- Wie soll gearbeitet werden? Ganz konkret: im gruppen (insgesamt waren es 32 Menschen) Geiste des iro-schottischen Christentums und – und durch – was für ein Geschenk – überwie- im weiteren Sinne – gemäß des westlichen Mys- gend sonnig-schönes Wetter! Die gemachten terienstromes, welcher in der Natur den Geist Erfahrungen vom Jahr zuvor wirkten positiv sucht, und diese durch den Menschen vergeis- und entspannend ins Soziale hinein. Größeres tigen möchte. Das wurde zum Programm: Eine Vertrauen und eine gewisse Selbstverständlich- Woche Geistesschulung in der Natur aus der keit waren stimmungsprägend. Wahrnehmung des Gegebenen. Denn Iona ist So gestalteten sich die Erlebnisse tiefer, näher, ein Welt-Ort dieser Geisteshaltung, nicht nur aber auch stiller und unspektakulärer. Sie er- historisch gesehen, sondern – so erleben es griffen mehr den Willen, sodass jetzt etwa die immer wieder Menschen – auch heute noch. Hälfte der Teilnehmenden an dem Zustande- Es gesellten sich in der Genese des ›Summer kommen der Tagung 2018 mitwirkt und immer Camps‹ – wie die Tagung gerne genannt wird, noch miteinander im Kontakt steht. Es wurde denn »Camp« betont noch mehr das Abenteuer begriffen, dass Anthroposophie über Erkennt- und die Naturnähe – weitere Mitstreiter dem nis hinausgehen muss in eine tatkräftige Verän- Vorhaben hinzu, genauso wie weitere inhalt- derung, die biographisch verortet, also existen- liche Ideale: Es sollte ganz kosmopolitisch of- ziell ist. -

Camphill and the Future

1 Camphill Generations All Camphillers would agree that theirs is a multiple-generation movement. But there is no shared understanding of where one Camphill generation ends and the next begins. The concept of a “generation” is inherently fuzzy. Since some people have children at age fifteen and others at age forty-five, three generations might pass in one family during another family’s single generation. Some groups of peo- ple, born at roughly the same time, attain a powerful sense of shared identity— most notably the baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) and the millennials (born between 1980 and 1996). There are also events in Camphill’s history that bonded specific generational cohorts together. At least four generations have left powerful imprints on Camphill. I use the term founding generation to include the circle of friends who fled from Vienna to Scotland in 1938 and undertook the shared project of creating a school for children with special needs. These founders were born between 1902 and 1916; all but the Königs were tightly grouped between 1910 and 1916. The second generation, which I refer to as “those who came,” includes children who enrolled in the early Camphill schools and coworkers, some only slightly younger than the founders, who joined the fledgling enterprise in the 1940s and 1950s. Baby boomersconstitute a third Camphill generation of students, villagers, and coworkers. A few arrived in the late 1960s, many more in the 1970s, and others as late as the 1990s or beyond. Because this was the period of most rapid growth, baby boomers became the most sig- nificant generation in Camphill’s history—a position they still hold today. -

Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 5/18

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 5/18 ■ Goetheanum May 2018 • N° 5 Goetheanum 1 Leadership: Letter to the members 9 Leadership: World Goetheanum Association Anthroposophical Society 2018 Annual Conference and Annual General Meeting 3 Response to the Annual General Goetheanum Leadership during the Meeting in other countries Goetheanum Leadership transition period up to the June retreat 5 Representative of Humanity (not in the picture: Matthias Girke) on the stage of the Main Letter to the Members Auditorium (Motion 12) 6 Members’ voices openly and make the processes more trans- 8 At the editors’ request: impressions Dear Members, parent for you as members. We see this as from a Council Member of the the best way forward to address the devel- Swiss Anthroposophical Society What is the situation at the Goetheanum? opment of isolated factions, the legitimate 10 Finland: new general secretary And what happens after the eventful Annual concerns about the further development Henri Murto General Meeting of the Anthroposophical in the Society and the rumours/suspicions 11 Argentina: new representative Horacio Müller Society in the week before Palm Sunday of various kinds which are unfortunately 12 Annual Motif: Rhythm and in Dornach? What are the consequences spreading rapidly. Movement (first rhythm) of the further terms of office of the execu- 15 Membership news tive members, Paul Mackay and Bodo von Sober stocktaking Plato, not having been confirmed by the After the intense and dramatic Easter event Forum General Assembly? at the Goetheanum (see below), there were 14 Corrections: agm minutes, Joan These questions concern many members. naturally great expectations directed to- Sleigh’s Travel Log A large number of messages from all over wards the first session of the Goetheanum 14 Appeal: Thomastik instruments the world have reached us in the Executive Leadership (Executive Council and Sec- 14 Appeal: Eliant petition for a more Council and the Goetheanum Leadership. -

VALENTIN TOMBERG: a PLATONIC SOUL Robert Powell, Phd

The following article first appeared in Starlight (2007), volume 7, no. 2, pages 9-12: VALENTIN TOMBERG: A PLATONIC SOUL Robert Powell, PhD A key to understanding Valentin Tomberg as a Platonist is given through his relationship with Elisabeth Vreede (1879-1943), one of Rudolf Steiner’s closest co-workers. Concerning Elisabeth Vreede, Rudolf Steiner indicated that she had incarnated earlier than planned and that she did this in order to meet Rudolf Steiner on Earth. He also saw her in connection with the Platonic stream.1 It is well known that at Plato’s Academy in Athens astronomy, arithmetic, geometry, and music were taught. Mathematics and astronomy have always been cultivated in the Platonic stream. Rudolf Steiner indicated this explicitly in connection with Elisabeth Vreede. In his lectures on Karmic Relationships Rudolf Steiner outlined how the people gathered around him belonged more to the Aristotelian stream. In this respect Elisabeth Vreede was an exception. She had incarnated earlier than planned in order to meet Rudolf Steiner. Because she came early, she had a very limited circle of friends.2 Those with whom she was karmically connected were not yet incarnated. However, upon meeting Valentin Tomberg she recognized him immediately as a significant figure from the Platonic stream and decided to actively support his deeply Christian anthroposophical impulse. She organized lectures for him and she was the person from whom it was possible to order Tomberg’s Biblical Meditations.3 She formed the bridge between the two great spiritual streams of the twentieth century: Rudolf Steiner Aristotelian stream Valentin Tomberg Platonic stream When Elisabeth Vreede was excluded from the Vorstand of the Anthroposophical Society, this meant the exclusion of the Platonic stream to which she belonged. -

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 6/18

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 6/18 ■ antroposophical society June 2018 • N° 6 General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophical Society 1 Contact by email? May we contact you by email? 2018 Annual Conference and agm 4 Switzerland: Respecting, understanding and Dear Members, implementing the results @ 5 Switzerland: Open discussion Anthroposophy Worldwide will take a new 6 Netherlands: A question step in 2019 and the General Anthroposophi- This shared awareness and participation is of perspective cal Society will make another attempt at to become possible for many more members 7 More members’ voices reaching as many members as possible in the future! 9 Meeting of all treasurers 13 Annual motif: The second electronically – wherever this is feasible. It can be achieved today via email and Foundation Stone For this we will need your help. the internet which means that there will be rhythm as a seed As an association of people of many no expensive printing and dispatching and 15 Membership News coun t ries, languages and cultural regions the most remote places can be reached be- the Anthroposophical Society and many cause most members have internet access. Anthroposophy Worldwide 2 Ireland: conference institutions inspired by Rudolf Steiner have We will make sure, however, that printed «Exploring Hibernia» spread across the whole world. To create a versions go out to those who wish for this newsletter for as many of the more than (subject to a charge). Goetheanum 40,000 members as possible and promote 3 Leadership: Second a shared awareness regarding questions of Fast and direct letter to the Members anthroposophy requires multilingualism In order to reach you quickly and directly 12 Leadership: World Goetheanum Association founded and the use of emails and the internet.