Local Identity, Democracy and Power Relations: a Case from the Ringerike Region, Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Silurian Oceanic Episodes and Events

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 150, 1993, pp. 501-513, 3 figs. Printed in Northern Ireland Early Silurian oceanic episodes and events R. J. ALDRIDGE l, L. JEPPSSON 2 & K. J. DORNING 3 1Department of Geology, The University, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK 2Department of Historical Geology and Palaeontology, SiSlvegatan 13, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden 3pallab Research, 58 Robertson Road, Sheffield $6 5DX, UK Abstract: Biotic cycles in the early Silurian correlate broadly with postulated sea-level changes, but are better explained by a model that involves episodic changes in oceanic state. Primo episodes were characterized by cool high-latitude climates, cold oceanic bottom waters, and high nutrient supply which supported abundant and diverse planktonic communities. Secundo episodes were characterized by warmer high-latitude climates, salinity-dense oceanic bottom waters, low diversity planktonic communities, and carbonate formation in shallow waters. Extinction events occurred between primo and secundo episodes, with stepwise extinctions of taxa reflecting fluctuating conditions during the transition period. The pattern of turnover shown by conodont faunas, together with sedimentological information and data from other fossil groups, permit the identification of two cycles in the Llandovery to earliest Weniock interval. The episodes and events within these cycles are named: the Spirodden Secundo episode, the Jong Primo episode, the Sandvika event, the Malm#ykalven Secundo episode, the Snipklint Primo episode, and the lreviken event. Oceanic and climatic cyclicity is being increasingly semblages (Johnson et al. 1991b, p. 145). Using this recognized in the geological record, and linked to major and approach, they were able to detect four cycles within the minor sedimentological and biotic fluctuations. -

Stortingstidende Referat Fra Møter I Stortinget

Stortingstidende Referat fra møter i Stortinget Nr. 74 · 8. mai Sesjonen 2017–2018 2018 8. mai – Grunnlovsforslag fra Kolberg, Christensen, Eldegard, Solhjell, K. Andersen og Lundteigen om vedtak 3745 av Grunnloven på tidsmessig bokmål Møte tirsdag den 8. mai 2018 kl. 10 Presidenten: Følgende innkalte vararepresentanter tar nå sete: President: Eva K r i st i n H a n s e n For Oslo: Mats A. Kirkebirkeland Dagsorden (nr. 74): For Sør-Trøndelag fylke: Kristian Torve Det foreligger to permisjonssøknader: 1. Innstilling fra kontroll- og konstitusjonskomiteen om Grunnlovsforslag fra Martin Kolberg, Jette F. – fra Senterpartiets stortingsgruppe om sykepermi- Christensen, Gunvor Eldegard, Bård Vegar Solhjell, sjon for representanten Åslaug Sem-Jacobsen fra og Karin Andersen og Per Olaf Lundteigen om vedtak med 8. mai og inntil videre av Grunnloven på tidsmessig bokmål – fra Arbeiderpartiets stortingsgruppe om permisjon (Innst. 249 S (2017–2018), jf. Dokument 12:11 (2015– for representanten Anniken Huitfeldt tirsdag 8. mai 2016)) grunnet oppgaver på frigjøringsdagen på Akershus 2. Innstilling fra kontroll- og konstitusjonskomiteen festning. om Grunnlovsforslag fra Martin Kolberg, Jette F. Christensen og Gunvor Eldegard om språklige juste- Etter forslag fra presidenten ble enstemmig besluttet: ringer i enkelte paragrafer i Grunnloven på nynorsk og Grunnlovsforslag fra Eivind Smith, vedtatt til 1. Søknadene behandles straks og innvilges. fremsettelse av Michael Tetzschner og Sylvi Graham, 2. Følgende vararepresentanter innkalles for å møte i om endring i §§ 17, 49, 50, 75 og 109 (retting av permisjonstiden: språklige feil etter grunnlovsendringene i 2014) For Akershus fylke: Mani Hussaini (Innst. 255 S (2017–2018), jf. Dokument 12:20 (2015– For Telemark fylke: Olav Urbø 2016) og Dokument 12:15 (2015–2016)) Presidenten: Mani Hussaini og Olav Urbø er til stede 3. -

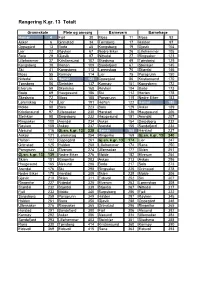

Rangering K.Gr. 13 Totalt

Rangering K.gr. 13 Totalt Grunnskole Pleie og omsorg Barnevern Barnehage Hamar 4 Fjell 30 Moss 11 Moss 92 Asker 6 Grimstad 34 Tønsberg 17 Halden 97 Oppegård 13 Bodø 45 Kongsberg 19 Gjøvik 104 Lier 22 Røyken 67 Nedre Eiker 26 Lillehammer 105 Sola 29 Gjøvik 97 Nittedal 27 Ringsaker 123 Lillehammer 37 Kristiansund 107 Skedsmo 49 Tønsberg 129 Kongsberg 38 Horten 109 Sandefjord 67 Steinkjer 145 Ski 41 Kongsberg 113 Lørenskog 70 Stjørdal 146 Moss 55 Karmøy 114 Lier 75 Porsgrunn 150 Nittedal 55 Hamar 123 Oppegård 86 Kristiansund 170 Tønsberg 56 Steinkjer 137 Karmøy 101 Kongsberg 172 Elverum 59 Skedsmo 168 Røyken 104 Bodø 173 Bodø 69 Haugesund 186 Ski 112 Horten 178 Skedsmo 72 Moss 188 Porsgrunn 115 Nedre Eiker 183 Lørenskog 74 Lier 191 Horten 122 Hamar 185 Molde 88 Sola 223 Sola 129 Asker 189 Kristiansund 97 Ullensaker 230 Harstad 136 Haugesund 206 Steinkjer 98 Sarpsborg 232 Haugesund 151 Arendal 207 Ringsaker 100 Arendal 234 Asker 154 Sarpsborg 232 Røyken 108 Askøy 237 Arendal 155 Sandefjord 234 Ålesund 116 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 238 Hamar 168 Harstad 237 Askøy 121 Lørenskog 254 Ringerike 169 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 240 Horten 122 Oppegård 261 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 174 Lier 247 Grimstad 125 Halden 268 Lillehammer 174 Rana 250 Porsgrunn 133 Elverum 274 Ullensaker 177 Skien 251 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 139 Nedre Eiker 276 Molde 182 Elverum 254 Skien 151 Ringerike 283 Askøy 213 Askøy 256 Haugesund 165 Ålesund 288 Bodø 217 Sola 273 Arendal 176 Ski 298 Ringsaker 225 Grimstad 278 Nedre Eiker 179 Harstad 309 Skien 239 Molde 306 Gjøvik 210 Skien 311 Eidsvoll 252 Ski 307 Ringerike -

Kartlegging Av Partienes Toppkandidaters Erfaring Fra Næringslivet Stortingsvalget 2021

Kartlegging av partienes toppkandidaters erfaring fra næringslivet Stortingsvalget 2021 I det videre følger en kartlegging av hvilken erfaring fra næringslivet toppkandidatene fra dagens stortingspartier i hver valgkrets har. Det vil si at i hver valgkrets, har alle de ni stortingspartiene fått oppført minst én kandidat. I tillegg er det kartlagt også for øvrige kandidater som har en relativt stor sjanse for å bli innvalgt på Stortinget, basert på NRKs «supermåling» fra juni 2021. I noen valgkretser er det derfor mange «toppkandidater». Dette skyldes at det er stor usikkerhet knyttet til hvilke partier som vinner de siste distriktsmandatene, og ikke minst utjevningsmandatene. Følgende to spørsmål har vært utgangspunktet for kartleggingen: 1. Har kandidaten drevet egen bedrift? 2. Har kandidaten vært ansatt daglig leder i en bedrift? Videre er kartleggingen basert på følgende kilder: • Biografier på Stortingets nettside. • Offentlig tilgjengelig informasjon på nettsider som Facebook, LinkedIn, Proff.no, Purehelp.no og partienes egne hjemmesider. • Medieoppslag som sier noe om kandidatenes yrkesbakgrunn. Kartleggingen har derfor flere mulige feilkilder. For eksempel kan informasjonen som er offentlig tilgjengelig, være utdatert eller mangelfull. For å begrense sjansen for feil, har kildene blitt kryssjekket. SMB Norge tar derfor forbehold om dette ved offentliggjøring av kartleggingen, eller ved bruk som referanse. Aust-Agder (3+1) Navn Parti Drevet egen bedrift? Vært daglig leder i en bedrift? Svein Harberg H Ja Ja Tellef Inge Mørland Ap Nei Nei Gro-Anita Mykjåland Sp Nei Nei Marius Aron Nilsen FrP Nei Nei Lætif Akber R Nei Nei Mirell Høyer- SV Nei Nei Berntsen Ingvild Wetrhus V Nei Nei Thorsvik Kjell Ingolf Ropstad KrF Nei Nei Oda Sofie Lieng MDG Nei Nei Pettersen 1 Akershus (18+1) Navn Parti Drevet egen bedrift? Vært daglig leder i en bedrift? Jan Tore Sanner H Nei Nei Tone W. -

Mo and Zn Minerallzations RELATED to GRANITES IN

Revista Brasileira de Geociências 17(4):571-5 77, dezembro de 1987 Mo AND Zn MINERALlZATIONS RE LATED TO GRANITES IN CALDERA ROOTS IN TH EELSJAE-AREA, OSLOPALEOR IFT, NORWAY SVEIN OLERUD* ABS T ~ AC T Th e Oslo Paleorift evolved in th e Pro terozoic basement of southeastern Norway and the Skagerak Sea in the Permian ; it form s a par t of a larger system of taphrogenic elements occurring at th e margin of th e Balt ic Sh ield . It consists of alkaline igneous rocks and Carnbro-Silurian sedim ents. Th e mo st prominent epigenetic mineralization ty pes are: A. intramagmatic Mo-depo sits; B. contact metasom atic c eposits (Zn , Pb , Fe etc.); C. rift margin deposits (Ag etc). Th e Elsjae area shows good examples of the A and B types. The Elsjae area is situated in th e northern part of the paleorift at the point of intersection be tween tw o dee ply erode d cald era struc tures. Cambro-Ordovician shales and Iimestones form a 2 krn 2 inlier enclosed in Permian ín tru sives. The sedime nts are co ntact metamorphosed and altered by met asomatic processes. Th e sphalerite mineralization is found in skarnaltered Iimestone layers an d lenses at severa l leveis in th e Cambro-Ordovician hornfelsed sedim ents. The Elsjae are a is unde rlain b y Permian granites which are hydrothermally altered and brecciated and carry low-grade molybdenite min erali zation in zones dominated by quartz-sericite-pyrite alte ration . Field evid en ces indicat e that th e Zn-skarn mineralization are related to the Storasyungen gran ite , which was intruded earlier th an the ring d yk e syste rn of th e calderas, while the Mo-mineralization was formed at a lat e stage in th e development of th e calderas. -

Supplementary File for the Paper COVID-19 Among Bartenders And

Supplementary file for the paper COVID-19 among bartenders and waiters before and after pub lockdown By Methi et al., 2021 Supplementary Table A: Overview of local restrictions p. 2-3 Supplementary Figure A: Estimated rates of confirmed COVID-19 for bartenders p. 4 Supplementary Figure B: Estimated rates of confirmed COVID-19 for waiters p. 4 1 Supplementary Table A: Overview of local restrictions by municipality, type of restriction (1 = no local restrictions; 2 = partial ban; 3 = full ban) and week of implementation. Municipalities with no ban (1) was randomly assigned a hypothetical week of implementation (in parentheses) to allow us to use them as a comparison group. Municipality Restriction type Week Aremark 1 (46) Asker 3 46 Aurskog-Høland 2 46 Bergen 2 45 Bærum 3 46 Drammen 3 46 Eidsvoll 1 (46) Enebakk 3 46 Flesberg 1 (46) Flå 1 (49) Fredrikstad 2 49 Frogn 2 46 Gjerdrum 1 (46) Gol 1 (46) Halden 1 (46) Hemsedal 1 (52) Hol 2 52 Hole 1 (46) Hurdal 1 (46) Hvaler 2 49 Indre Østfold 1 (46) Jevnaker1 2 46 Kongsberg 3 52 Kristiansand 1 (46) Krødsherad 1 (46) Lier 2 46 Lillestrøm 3 46 Lunner 2 46 Lørenskog 3 46 Marker 1 (45) Modum 2 46 Moss 3 49 Nannestad 1 (49) Nes 1 (46) Nesbyen 1 (49) Nesodden 1 (52) Nittedal 2 46 Nordre Follo2 3 46 Nore og Uvdal 1 (49) 2 Oslo 3 46 Rakkestad 1 (46) Ringerike 3 52 Rollag 1 (52) Rælingen 3 46 Råde 1 (46) Sarpsborg 2 49 Sigdal3 2 46 Skiptvet 1 (51) Stavanger 1 (46) Trondheim 2 52 Ullensaker 1 (52) Vestby 1 (46) Våler 1 (46) Øvre Eiker 2 51 Ål 1 (46) Ås 2 46 Note: The random assignment was conducted so that the share of municipalities with ban ( 2 and 3) within each implementation weeks was similar to the share of municipalities without ban (1) within the same (actual) implementation weeks. -

Anbefaling Om Statlig Forskrift for Kommunene I Viken Og Gran Kommune I Innlandet Fra Midnatt Natt Til 16.3.2021

15.3.2021 Anbefaling om statlig forskrift for kommunene i Viken og Gran kommune i Innlandet fra midnatt natt til 16.3.2021 Oppsummering • Helsedirektoratet anbefaler iverksettelse av tiltak i samsvar med covid-19-forskriften kapittel 5A for kommunene i Viken fylke og Gran kommune i Innlandet • Tiltakene anbefales iverksatt fra midnatt natt til 16.3.2021 med varighet til og med 11. april 2021 • I møte med Statsforvalteren i Oslo og Viken, kommunene, FHI og Helsedirektoratet svarte 23 kommuner at de ønsket å bli omfattet av kapittel 5A i Covid-19 forskriften, 13 svarte nei, 3 var usikre og de øvrige tok ikke ordet i møtet. Statsforvalter begynte møtet med at hun ønsket at de kommunene som ikke ønsket å bli omfattet av forskriften tok ordet. Gran kommune i Innlandet ønsket å omfattes av forskriften på grunn av nærhet til Lunner og tett kontakt til Oslo. • Helsedirektoratet og FHI mener det er behov for sterke tiltak i kommuner som har en raskt økende smittetrend. Det er betydelig forskjell på smittetrykket mellom ulike kommuner i Viken. Likevel vil Helsedirektoratet og FHI anbefale at vedtaket omfatter hele fylket. I Viken dominerer den engelske virusvarianten med økt smittsomhet. Det er behov for tiltak som begrenser mobilitet gjennom pendling og sosiale og kulturelle aktiviteter mellom kommunene. Over halvparten av kommunene i Viken melder om utfordringer med TISK-kapasiteten. Kapasiteten i spesialisthelsetjenesten i Helse Sør-Øst er presset klinisk på grunn et høyt antall innleggelser og på laboratoriene på grunn av høyt prøvevolum. • Kommunene må til enhver tid konkret vurdere behovet for lokale vedtak og anbefalinger i tillegg, avhengig av den lokale smittesituasjonen. -

Velferdskonferansen 2012 - Programutkast Bekreftelse Er Mottatt Fra De Oppførte Personene, Med Mindre Annet Er Oppgitt

Velferdskonferansen 2012 - Programutkast Bekreftelse er mottatt fra de oppførte personene, med mindre annet er oppgitt. Mandag 21. mai 10.00 – 10.10: Åpning Kulturinnslag: Sara Ramin Osmundsen 10.10 – 12.30: Ulikhet og sosialt opprør Verden over foregår det en omfattende kamp om fordelingen av samfunnets ressurser og de verdiene som skapes gjennom arbeid. Fordelingen av verdiene i samfunnet er nært knyttet til demokratisk styring, omfordeling gjennom skattesystemet og eksistensen av universelle offentlige ytelser som kommer alle til gode. I siste instans dreier det seg om fordelingen av økonomisk og politisk makt. Navn: Sue Christoforou, The Equality Trust Josefin Brink, Riksdagsmedlem Vänsterpartiet Rolf Aaberge, seniorforsker SSB Politikerdebatt- Finanspolitiske talspersoner: Knut Storberget (AP) (bekreftet), Jan Tore Sanner (H) (ikke bekreftet), Inga Marte Thorkildsen (SV)(bekreftet), Per Olaf Lundteigen (SP) (bekreftet), Borghild Tenden (V) (ikke bekreftet), Torstein Dahle (Rødt) (bekreftet), Kjetil Solvik Olsen (Frp) (ikke bekreftet), Hans- Olav Syversen, (Krf) (ikke bekreftet) Møteleder: Nina Hansen, journalist og forfatter Lunsj 13.30 – 15.30: Parallellseminar A A1: Forskjells-Norge Økonomisk utjevning kommer ikke av seg selv. Det er resultat av en samfunnsmessig kamp. I Norge, som i mange andre land, førte denne kampen til oppbygging av en omfattende offentlig sektor, et skattesystem som omfordeler og et sentralt lønnsforhandlingssystem som har bidratt til at inntekt fordeles jevnere. Utviklingen av universelle tjenester ga like rettighetter til utdanning, helsetjenester og sosiale ytelser for alle, samt lik tilgang til grunnleggende infrastruktur. Hvordan har utviklingen vært i Norge? Hva er situasjonen i dag? Hva er grepene for en rettferdig fordeling? Navn: (Avventer booking til plenumsinnlederne er på plass for å sikre at dette seminaret skiller seg fra plenumsinnledninga. -

Politisk Regnskap for 2010

VENSTRES STORTINGSGRUPPE POLITISK REGNSKAP 2010 Miljø, kunnskap, nyskaping og fattigdoms- bekjempelse Oslo, 23.06.10 Dokumentet finnes i klikkbart format på www.venstre.no 2 1. STORTINGSGRUPPA Venstres stortingsgruppe består i perioden 2005-09 av Trine Skei Grande (Oslo) og Borghild Tenden (Akershus). Trine Skei Grande er representert i kirke-, utdannings- og forskningskomiteen og kontroll- og konstitusjonskomiteen. Borghild Tenden er representert i finanskomiteen. Abid Q. Raja har møtt som vararepresentant for Borhild Tenden i perioden 1. til 16. oktober 2009, 30. november til 5. desember 2009 og fra 17. til 25. mars 2010. Stortingsgruppa har seks ansatte på heltid. 2. VIKTIGE SAKER FOR STORTINGSGRUPPA Venstres stortingsgruppe har valgt noen områder hvor vi mener det er behov for en mer offensiv og tydligere kurs. Ved siden av å forsvare liberale rettigheter har Venstres stortingsgruppe denne perioden derfor prioritert kunnskap, miljø og selvstendig næringsdrivende. Denne prioriteringen er synlig både i Venstres alternative budsjetter, i forslag som er fremmet på Stortinget og spørsmål som er stilt til statsrådene. I tillegg har Venstres stortingsgruppe vist at vi vil prioritere mer til dem som trenger det mest; både gjennom representantforslag for å bekjempe fattigdom hos barn, en bedre rusbehandling og et bedre barnevern. Venstre fremmet også et eget forslag om en velferdsreform som ble behandlet sammen med samhandlingsreformen. På Venstres landsmøte tidligere i år pekte Venstres nyvalgte leder, Trine Skei Grande, på fem utvalgte områder som vil være Venstres hovedprioritet den kommende tiden. Hun lovet at Venstre skal prioritere en milliard mer årlig til lærere, forskning, selvstendig næringsdrivende og småbedrifter, jernbane og for å bekjempe fattigdom. -

Timothy K.M. Beatty and Dag Einar Sommervoll Discrimination In

Discussion Papers No. 547, June 2008 Statistics Norway, Research Department Timothy K.M. Beatty and Dag Einar Sommervoll Discrimination in Europe Evidence from the Rental Market Abstract: This paper considers statistical discrimination in rental markets, using a rich data set on rental contracts from Norway. We find that tenants born abroad pay a statistically significant and economically important premium for their dwelling units after controlling for a comprehensive set of apartment, individual and contract specific covariates. We also find that the premium is largest for tenants of African origin. Moreover, the children of parents born abroad also face a statistically significant and economically important rental premium. Keywords: Statistical Discrimination, Rental Markets, Hedonic Regression JEL classification: J15, R21 Address: Timothy K.M. Beatty, Department of Economics, University of York. E-mail: Dag Einar Sommervoll, Research Department, Statistics Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Discussion Papers comprise research papers intended for international journals or books. A preprint of a Discussion Paper may be longer and more elaborate than a standard journal article, as it may include intermediate calculations and background material etc. Abstracts with downloadable Discussion Papers in PDF are available on the Internet: http://www.ssb.no http://ideas.repec.org/s/ssb/dispap.html For printed Discussion Papers contact: Statistics Norway Sales- and subscription service NO-2225 Kongsvinger Telephone: +47 62 88 55 00 Telefax: +47 62 88 55 95 E-mail: [email protected] 1. Introduction Price discrimination is consistent with profit maximizing behavior. Discrimination based on ethnicity is inconsistent with societal norms as expressed in national and international law. -

Upcoming Projects Infrastructure Construction Division About Bane NOR Bane NOR Is a State-Owned Company Respon- Sible for the National Railway Infrastructure

1 Upcoming projects Infrastructure Construction Division About Bane NOR Bane NOR is a state-owned company respon- sible for the national railway infrastructure. Our mission is to ensure accessible railway infra- structure and efficient and user-friendly ser- vices, including the development of hubs and goods terminals. The company’s main responsible are: • Planning, development, administration, operation and maintenance of the national railway network • Traffic management • Administration and development of railway property Bane NOR has approximately 4,500 employees and the head office is based in Oslo, Norway. All plans and figures in this folder are preliminary and may be subject for change. 3 Never has more money been invested in Norwegian railway infrastructure. The InterCity rollout as described in this folder consists of several projects. These investments create great value for all travelers. In the coming years, departures will be more frequent, with reduced travel time within the InterCity operating area. We are living in an exciting and changing infrastructure environment, with a high activity level. Over the next three years Bane NOR plans to introduce contracts relating to a large number of mega projects to the market. Investment will continue until the InterCity rollout is completed as planned in 2034. Additionally, Bane NOR plans together with The Norwegian Public Roads Administration, to build a safer and faster rail and road system between Arna and Stanghelle on the Bergen Line (western part of Norway). We rely on close -

The Nature of Ordovician Limestone-Marl Alternations in the Oslo-Asker District

.re./sereprs OPEN The nature of Ordovician limestone-marl alternations in the Oslo-Asker District (Norway): reee: 1 e 01 epe: 0 eer 01 witnesses of primary glacio-eustasy se: 07 r 016 or diagenetic rhythms? Chloé E. A. Amberg1, Tim Collart2, Wout Salenbien2,3, Lisa M. Egger4,5, Axel Munnecke4, Arne T. Nielsen6, Claude Monnet1, Øyvind Hammer7 & Thijs R. A. Vandenbroucke1,2 Ordovician limestone-marl alternations in the Oslo-Asker District have been interpreted as signaling glacio-eustatic lowstands, which would support a prolonged “Early Palaeozoic Icehouse”. However, these rhythmites could alternatively refect diferential diagenesis, without sedimentary trigger. Here, we test both hypotheses through one Darriwilian and three Katian sections. Our methodology consists of a bed-by-bed analysis of palynological (chitinozoan) and geochemical (XRF) data, to evaluate whether the limestone/marl couplets refect an original cyclic signal. The results reveal similar palynomorph assemblages in limestones and marls. Exceptions, which could be interpreted as refecting palaeoclimatological fuctuations, exist at the species level: Ancyrochitina bornholmensis seems to be more abundant in the marl samples from the lower Frognerkilen Formation on Nakkholmen Island. However, these rare cases where chitinozoans difer between limestone/marl facies are deemed insufcient for the identifcation of original cyclicity. The geochemical data show a near-perfect correlation between insoluble elements in the limestone and the marls, which indicates a similar composition of the potential precursor sediment, also in the Frognerkilen Formation. This is consistent with the palynological data. Although an original cyclic pattern could still be recorded by other, uninvestigated parameters, our palaeontological and geochemical data combined do not support the presence of such a signal.