THE THREE ARCHBISHOPS of the HOUSE of BETHUNE/BEATON! This Is a Paper Which Might Be About the Reformation in Scotland but It Is Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No. 18 December 2019 INDSIDE - Parish news stories; Lourdes reports, Our pilgrims in Spain and Italy, Schools and Youth News Emotional welcome for the Little Flower What a grace-filled event it was for our for everyone present. It seemed to everyone diocese to have the relics of St Therese of that her saintly presence was enough as she Lisieux visit us in our own St Andrews spoke in the silence of everyone’s heart. Cathedral in September. It was as though Therese, one of the most popular saints in Therese had come not for herself but for the history of the Church, had indeed come everyone in every diocese in Scotland and to visit us to inspire us, to encourage us, the people present were delighted that she and just to be present with us for a few days was really here in our Diocese of Dunkeld where she will listen to us and speak to us with devotees, young and old, who loved in the depths of our hearts. Never has the her and wished to spend some time in her Cathedral been so bedecked with so many physical and spiritual presence. Most of all beautiful roses, symbols of her great love to learn from her. The good humour spread Fr Anthony McCarthy, parish priest for God and her promise to all of her devo- quickly among the congregation, and the of Our Lady of Good Counsel, Broughty tees. sense of incredulity at her closeness was Ferry, died on Thursday 10th October, awesome. -

Galloway's Bishop-Elect in Prayer Call

Year for CAMPAIGN LIFE SUPREME KNIGHT CONSECRATED 2017 launched honour LIFE begins at ladies returns to on Sunday. pro-life lunch. Glasgow. Page 3 Page 2 Page 8 No 5597 BLESSINGS ON THE FEAST OF ST ANDREW ON NOVEMBER 30 Friday November 28 2014 | £1 EUROPE TOLD BY POPE FRANCIS TO RESPECT LIFE By Ian Dunn POPE Francis told members of the European Parliament on Tuesday that they must end the treatment of ‘the unborn, terminally ill, and the elderly’ as objects and embrace a new fairer immigration policy of acceptance. In a second speech the same day, the Pope also told the Council of Europe that human trafficking was the new slavery of our age, depriving its victims of all dignity. The Holy Father was speaking at the European Parliament in Strasbourg during a brief visit meant to highlight his vision for Europe a quarter-century after St John Paul II travelled there to address a continent still divided by the Iron Curtain. “Despite talk of human rights, too many people are treated as objects in Europe: unborn, terminally ill, and the elderly,” the Pope told MEPs. “We’re too tempted to throwaway lives we don’t see as ‘useful.’ Upholding the dignity of the person means acknowledging the value of the gift of human life.” He said that ‘killing [children]… before they’re born is the great mistake that happens when technology is allowed to take over’ and is ‘the Pope Francis shakes hands with Martin Schulz, inevitable consequence of a throwaway culture.’ president of the European Parliament, while visiting the European Parliament in Strasbourg I Continued on page 6 Galloway’s bishop-elect in prayer call I Fr William Nolan, ‘gobsmacked’ over Pope Francis’ appointment, asks for parishioners to pray for him By Ian Dunn seeds of Faith so long ago,” The new bishop added that his experience in many pastoral situations, He said he was glad that his ordination parishioners were delighted for him. -

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

February Magazine Web

Rector Rev Kirstin Freeman February 2020 Magazine E-mail [email protected] Other contacts can be found on the printed copy in the church Web Site: http://bearsden.church.scot Web Site Co-ordinator: Janet Stack ([email protected]) All Saints is a registered charity in Scotland SCO005552 Cover picture : Rt Revd Kevin Pearson our bishop-elect All Saints Scottish Episcopal Church Drymen Road, Bearsden £1 A new bishop for the Diocese already know many in the Diocese but are also looking forward to living there and getting to know the people and the area better. We shall be very sad to be leaving The Right Reverend Kevin Pearson was elected as the new Bishop of Glasgow and the people of Argyll and The Isles which we have grown to love deeply over nine Galloway, on Saturday 18 th January. Bishop Kevin is currently the Bishop of Argyll years of ministry there.” and The Isles and his election to Glasgow and Galloway represents a historic Bishop Kevin is married to Dr Elspeth Atkinson who is Chief Operating Officer for the “translation” of a Bishop from one See to another. Bishop Kevin will take up his new Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews & Edinburgh. Prior to that Elspeth was post at a service of installation later in the year, on a date to be announced in due Director of MacMillan Cancer Support in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales and course. for most of her career held senior roles in Economic Development in Scotland. Bishop Kevin has served as Bishop of Argyll and The Isles since February 2011 and before that was Rector of St Michael & All Saints Church in Edinburgh, Canon of St Requiem a nd Service of Dedication Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, Dean of the Diocese of Edinburgh and the Provincial Director of Ordinands. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Gavin Douglas Was Born to Be Conservative. Embedded in Feudalism and the Pre Counter Reformation Church He Was Not the Kind of Person to Cause a Ripple in History

12 TWO ASPECTS OF GAVIN DOUGLASO Gavin Douglas was born to be conservative. Embedded in feudalism and the pre Counter Reformation church he was not the kind of person to cause a ripple in history. Literature gave him his fame. There single handed with his translation of Vergil's Aeneid he brought Scotland into the Renaissance. History robbed him of the influence he might have had. The manuscripts of his Aeneid were put away and forgotten, and by the time they were brought to light his language had become obsolete, so now a not infrequent response to the mention of his name is 'Who's he?'. 'He' was two years younger than James IV and finished his Aeneid translation in 1513, the same year as Flodden. Flodden was especially tragic because it came at a time when the nobles, of whom so many fell, were still very important to Scotland. In England and France feudalism might be looking at the beginning of the end because substitution of money for service was making barons no longer indispensable, but in Scotland not only was Lowland feudalism influenced by Highland clan ideals but the continual succession to the throne of minors had nobles playing an indispensable if not always concerted part in government. When Gavin Douglas was a boy feudalism was fighting fit. James III was the king who upset the nobles by preferring the company of a group of commoners to theirs. He more than upset them when he conferred a title on his architect friend Cochrane. Cochrane not only upgraded his attire and took to going round with a small entourage, which after all was only airs and graces, but he also interposed himself between the king and petitioners. -

The Diocese of Sodor Between N I Ð Aróss and Avignon – Rome, 1266

Theð diocese of Sodor between Ni aróss and Avignon – Rome, 1266-1472 Sarah E. Thomas THE organisation and administration of the diocese of Sodor has been discussed by a number of scholars, either jointly with Argyll or in relation to 1 ð Norway. In 1266 the diocese of Sodor or Su reyjar encompassed the Hebrides and the Isle of Man, but by the end of the fourteenth century, it was divided between the Scottish Hebrides and English Man. The diocese’s origins lay in the Norseð kingdom of the Isles and Man and its inclusion in the province of Ni aróss can be traced back to the actions of Olaf 2 Godredsson in the 1150s.ð After the Treaty of Perth of 2 July 1266, Sodor remained within the Ni aróss church province whilst secular sovereignty 3 and patronage of the see had been transferred to the King of Scots. However, wider developments in the Christian world and the transfer of allegiance of Hebridean secular ðrulers from Norway to Scotland after 1266 would loosen Sodor’s ties to Ni aróss. This article examines the diocese of Sodor’s relationship with its metropolitan and the rather neglected area of its developing links with the papacy. It argues that the growing 1 A.I. Dunlop, ‘Notes on the Church in the Dioceses of Sodor and Argyll’, Records of the Scottish Church History Society 16 (1968) [henceforth RSCHS]; I.B. Cowan, ‘The Medieval Church in Argyll and the Isles’, RSCHS 20 (1978-80); A.D.M. Barrell, ‘The church in the West Highlands in the late middle ages’, Innes Review 54 (2003); A. -

Green Light Signals Quest for Auxiliary

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name JULY 2015 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p Joie de vivre! A SPIRIT of joy filled St Andrew’s Cathedral as children and young people with additional support needs joined Archbishop Philip Tartaglia for Mass. The theme ‘Rejoice’ reflected the Gospel passage of Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth – whose child in her womb leapt for joy. The Archbishop spoke of the gifts of life and love and the great joy which the births of John the Baptist and Jesus brought to the world. He encouraged the young people to rejoice and reflect that joy in caring for others and looking after the world. Glasgow Lord Provost Sadie Docherty joined in the celebrations. Picture by Paul McSherry Green light Caritas Glasgow to get signals quest Award another bishop for auxiliary Pope Francis has agreed diocesan bishop’s closest col - with Bishop Joseph Devine the green light to his request, By Vincent Toal laborator, he is expected to be who moved to Motherwell in Archbishop Tartaglia has in - to provide an auxiliary involved in all pastoral proj - 1983. Bishop John Mone then vited people to write to him by bishop for the Arch- an auxiliary following his ects, decisions and diocesan served as auxiliary for four 15 August with preferred pages diocese of Glasgow fol - health scare at the beginning initiatives. years before his appointment names. lowing a request from of the year. With Glasgow embarked on to Paisley in 1988. He will then make a formal 6,7,10,11 Archbishop Philip In an ad clerum letter, sent a wide-ranging review of Although usually chosen submission to the Apostolic out this week, he stated: “I am parish pastoral provision, the from among the diocesan Nuncio who conducts a Tartaglia. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Kilwinning-Abbey-By-Ja-Ness.Pdf

John Ness was a keen local historian with a large collection of papers, books, pamphlets, charts and letters about Kilwinning and district, but being before the days of computers and the Internet, collating and editing this booklet would surely have meant many long hours searching through piles of books and notes. It was originally published in 1967, no doubt as part of the Abbey Church’s 400th anniversary celebrations (albeit a year or two late if the dates are correct), and was one of only a few collected sources of information about the Abbey. Of course, it is now long out of print and only a few dog-eared copies exist in libraries, but now it is accessible to the public once more. To make it easier to read on a computer screen, it hasn’t been recreated in its completely original form, but I have more or less kept the same layout. I made a few minor changes, adding a few commas here and there to make the sometimes slightly awkward sentence construction easier to read. If something reads a little strangely to modern eyes, that was the author’s style. Also, I corrected a very few obvious printing errors, and standardised words and phrases that were in bold type for no good reason. Full- or half-page photos which were in the middle of the booklet are now placed at the end. This is not meant as an academic work, so if anyone reads a statement which they believe is inaccurate or just plain wrong, the mistake is not mine. -

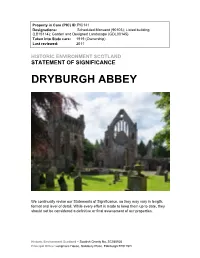

Dryburgh Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 141 Designations: Scheduled Monuent (90103); Listed building (LB15114); Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00145) Taken into State care: 1919 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DRYBURGH ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DRYBURGH ABBEY SYNOPSIS Dryburgh Abbey comprises the ruins of a Premonstratensian abbey, founded in 1150 by Hugh de Morville, constable of Scotland. The upstanding remains incorporate fine architecture from the 12th, 13th and 15th centuries. Following the Protestant Reformation (1560) the abbey passed through several secular hands, until coming into the possession of David Erskine, 11th earl of Buchan, who recreated the ruin as the centrepiece of a splendid Romantic landscape. Buchan, Sir Walter Scott and Field-Marshal Earl Haig are all buried here. While a greater part of the abbey church is now gone, what does remain - principally the two transepts and west front - is of great architectural interest. The cloister buildings, particularly the east range, are among the best preserved in Scotland. The chapter house is important as containing rare evidence for medieval painted decoration. The whole site, tree-clad and nestling in a loop of the River Tweed, is spectacularly beautiful and tranquil.