Constructing Safety in Scuba Diving: a Discursive Psychology Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scuba Diving History

Scuba diving history Scuba history from a diving bell developed by Guglielmo de Loreno in 1535 up to John Bennett’s dive in the Philippines to amazing 308 meter in 2001 and much more… Humans have been diving since man was required to collect food from the sea. The need for air and protection under water was obvious. Let us find out how mankind conquered the sea in the quest to discover the beauty of the under water world. 1535 – A diving bell was developed by Guglielmo de Loreno. 1650 – Guericke developed the first air pump. 1667 – Robert Boyle observes the decompression sickness or “the bends”. After decompression of a snake he noticed gas bubbles in the eyes of a snake. 1691 – Another diving bell a weighted barrels, connected with an air pipe to the surface, was patented by Edmund Halley. 1715 – John Lethbridge built an underwater cylinder that was supplied via an air pipe from the surface with compressed air. To prevent the water from entering the cylinder, greased leather connections were integrated at the cylinder for the operators arms. 1776 – The first submarine was used for a military attack. 1826 – Charles Anthony and John Deane patented a helmet for fire fighters. This helmet was used for diving too. This first version was not fitted to the diving suit. The helmet was attached to the body of the diver with straps and air was supplied from the surfa 1837 – Augustus Siebe sealed the diving helmet of the Deane brothers’ to a watertight diving suit and became the standard for many dive expeditions. -

History of Scuba Diving About 500 BC: (Informa on Originally From

History of Scuba Diving nature", that would have taken advantage of this technique to sink ships and even commit murders. Some drawings, however, showed different kinds of snorkels and an air tank (to be carried on the breast) that presumably should have no external connecons. Other drawings showed a complete immersion kit, with a plunger suit which included a sort of About 500 BC: (Informaon originally from mask with a box for air. The project was so Herodotus): During a naval campaign the detailed that it included a urine collector, too. Greek Scyllis was taken aboard ship as prisoner by the Persian King Xerxes I. When Scyllis learned that Xerxes was to aack a Greek flolla, he seized a knife and jumped overboard. The Persians could not find him in the water and presumed he had drowned. Scyllis surfaced at night and made his way among all the ships in Xerxes's fleet, cung each ship loose from its moorings; he used a hollow reed as snorkel to remain unobserved. Then he swam nine miles (15 kilometers) to rejoin the Greeks off Cape Artemisium. 15th century: Leonardo da Vinci made the first known menon of air tanks in Italy: he 1772: Sieur Freminet tried to build a scuba wrote in his Atlanc Codex (Biblioteca device out of a barrel, but died from lack of Ambrosiana, Milan) that systems were used oxygen aer 20 minutes, as he merely at that me to arficially breathe under recycled the exhaled air untreated. water, but he did not explain them in detail due to what he described as "bad human 1776: David Brushnell invented the Turtle, first submarine to aack another ship. -

Mark V Diving Helmet

Historical Diver, Number 5, 1995 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 06/10/2021 19:38:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30848 IDSTORI DIVER The Offical Publication of the Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Number 5 Summer 1995 "Constant and incessant jerking and pulling on the signal line or pipe, by the Diver, signifies that he must be instantly pulled up .... " THE WORLDS FIRST DIVING MANUAL Messrs. C.A. and John Deane 1836 "c:lf[{[J a:tk o{ eadz. u.adn l;t thi:1- don't di£ wllfzoul fz.a1Jin5 Co't'towe.J, dofen, pwu!.hau:d O'l made a hefmd a{ :toorh, to gfimju.e (o'r. !JOU'tul{ thl:1 new wo'l.fJ''. 'Wifl'iam 'Bube, "'Beneath 'J,opic dlw;" 1928 HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY HISTORICAL DIVER MAGAZINE USA The official publication of the HDSUSA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NON-PROFIT CORPORATION HISTORICAL DIVER is published three times a year C/0 2022 CLIFF DRIVE #119 by the Historical Diving Society USA, a Non-Profit SANTA BARBARA, CALIFORNIA 93109 U.S.A. Corporation, C/0 2022 Cliff Drive #119 Santa Barbara, (805) 963-6610 California 93109 USA. Copyright© 1995 all rights re FAX (805) 962-3810 served Historical Diving Society USA Tel. (805) 963- e-mail HDSUSA@ AOL.COM 6610 Fax (805) 962-3810 EDITORS: Leslie Leaney and Andy Lentz. Advisory Board HISTORICAL DIVER is compiled by Lisa Glen Ryan, Art Bachrach, Ph.D. J. Thomas Millington, M.D. Leslie Leaney, and Andy Lentz. -

Interpreting Penobscot Indian Dispossession Between 1808 and 1835 Jacques Ferland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine Maine History Volume 43 Article 3 Number 2 Reconstructing Maine's Wabanaki History 8-1-2007 Tribal Dissent or White Aggression?: Interpreting Penobscot Indian Dispossession Between 1808 and 1835 Jacques Ferland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/ mainehistoryjournal Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ferland, Jacques. "Tribal Dissent or White Aggression?: Interpreting Penobscot Indian Dispossession Between 1808 and 1835." Maine History 43, 2 (2007): 124-170. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol43/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Neptune served as Lieutenant-Governor of the Penobscot Nation for over fifty years. He, along with Tribal Governor John Attean, presided over the tribe during a period of turmoil in Penobscot history — a time marked by land dis- possession and subsequent tribal division in the first part of the nineteenth cen- tury. The portrait was painted by Obadiah Dickinson in 1836 and hung in the Blaine House for many years. Courtesy of the Maine Arts Commission. TRIBAL DISSENT OR WHITE AGGRESSION?: INTERPRETING PENOBSCOT INDIAN DISPOSSES- SION BETWEEN 1808 AND 1835. BY JACQUES FERLAND “I now come to the time when our Tribe was separated into two fac- tions[,] the old and the new Party. I am sorry to speak of it as it was very detrimental to our tribe as there was but few of us the remnant of a once powerful tribe.” So spoke Penobscot tribal leader John Attean, re- calling the 1834-1835 breach in tribal politics that shook the edifice of community and cohesion among the Penobscot people. -

Idstorical Diver

Historical Diver, Number 3, 1994 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 09/10/2021 13:15:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30846 IDSTORICAL DIVER Number 3 Summer 1994 The Official Publication of the Historical Diving Society U.S.A As you will by now know, the Society has relocated to Santa Barbara, California and this move, along with various other Society developments has delayed the publication of the Spring '94 issue of HISTORICAL DIVER. By way of catching up, we have produced a Summer double issue and have the good fortune to be able to publish with a color cover. Coinciding with the Santa Barbara relocation is the appointment, by the Board of Directors, of the first members of the HDS USA Advisory Board. This distinguished group of senior diving professionals, with extensive backgrounds in diving medicine, technical development, commercial, military and sports diving, bring in excess of 300 years of diving experience to the Society. Most of their biographies are the size of town phone directories, and have had to be severely edited for publication. We are honored and gratefulfortheir willing offers of service, and hope that we have done their biographies justice. Details start on page 4. The recently introduced, Founding Benefactor class of membership has proven to be very popular with over half of the thirty available memberships already taken. An opportunity still exists to acquire one of these unique memberships and details of it's benefits are noted on page 9. On the international front, the ongoing formation of the HDS USA as a nonprofit corporation has, by law, changed the conditions that govern our relationship with the HDS in UK. -

Another Whitstable Trade

doi:10.3723/ut.29.101 International Journal of the Society for Underwater Technology, Vol 29, No 2, pp 101–102, 2010 Another not make it physically an easy Engineering Applications', `Div- read and is best suited to either ing Equipment Manufacturers', Book Review Whitstable a formal library situation or to `Notable Divers' and an area dip into on many short occasions much misunderstood during Trade: An such as a `coffee table'; however, early diving, `Physiology and Illustrated the book is a serious text and medicine'. Within these sections should be respected as such. there are too many aspects to History of The basic theme of the book, cover in a short review but they and specifically in the first sec- include development of military Helmet Diving tion, describes the development diving by Col Pasley, Royal of helmet diving in Whitstable Engineers (yes, the Army taught John Bevan and how it spread from there to the Navy to dive!), the Liverpool the rest of the United Kingdom Salvage Company, details of and indeed to the rest of the main equipment manufacturers' Published by SUBMEX, Gosport, world. The early development in work (e.g. Augustus Siebe and 2009 Whitstable is split into six peri- CE Heinke) and divers such as ods commencing with the Deane William Walker and his work ISBN 978 0 9508242 5 9 brothers from 1829 to 1856 mov- under Winchester Cathedral. 436 pages; ¿79 ing through other family peri- The early history of diving ods to the Whitstable Salvage illnesses is the shortest and least This book is a significant histor- Company from 1898 to 1926. -

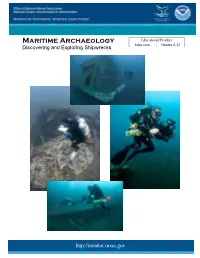

Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Educational Product Maritime Archaeology Educators Grades 6-12 Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Acknowledgement This educator guide was developed by NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. This guide is in the public domain and cannot be used for commercial purposes. Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction, without alteration, of this guide on the condition its source is acknowledged. When reproducing this guide or any portion of it, please cite NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary as the source, and provide the following URL for more information: http://monitor.noaa.gov/education. If you have any questions or need additional information, email [email protected]. Cover Photo: All photos were taken off North Carolina’s coast as maritime archaeologists surveyed World War II shipwrecks during NOAA’s Battle of the Atlantic Expeditions. Clockwise: E.M. Clark, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Dixie Arrow, Photo: Greg McFall, NOAA; Manuela, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Keshena, Photo: NOAA Inside Cover Photo: USS Monitor drawing, Courtesy Joe Hines http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Monitor National Marine Sanctuary Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and exploring Shipwrecks _____________________________________________________________________ An Educator -

Let's Go Diving-1828! Mask, Scuba Tank and B.C

NUMBER21 FALL 1999 Let's Go Diving-1828! Mask, scuba tank and B.C. Lemaire d 'Augerville's scuba gear • Historical Diver Pioneer Award -Andre Galeme • E.R. Cross Award - Bob Ramsay • • DEMA Reaching Out Awards • NOGI • • Ada Rebikoff • Siebe Gorman Helmets • Build Your Own Diving Lung, 1953 • • Ernie Brooks II • "Big" Jim Christiansen • Don Keach • Walter Daspit Helmet • Dive Industry Awards Gala2000 January 20, 2000 • Bally's Hotel, Las Vegas 6:30pm- Hors d'oeuvres & Fine Art Silent Auction 7:30pm- Dinner & Awards Ceremony E.R. Cross Award NOGIAwards Reaching Out Awards Academy of Diving Equipment & Historical Diving Underwater Marketing Association Pioneer Award Arts & Sciences Historical Diving Society Thank you to our Platinum Sponsor Thank you to our Gold Sponsors 0 Kodak OCEANIC 1~1 Tickets: $125 individual, $200 couple* • Sponsor tables available. (*after January 1, couples will be $250) For sponsor information or to order tickets, call: 714-939-6399, ext. 116, e-mail: [email protected] or write: 2050 S. Santa Cruz St., Ste. 1000, Anaheim, CA 92805-6816 HISTORICAL DIVER Number21 ISSN 1094-4516 Fa111999 CONTENT HISTORICAL DIVER MAGAZINE PAGE ISSN 1094-4516 5 1999 Historical Diver Pioneer Award- Andre Galeme THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF 6 HDSUSA 2000 Board of Directors 7 HDSUSA Advisory Board Member - Ernest H. Brooks II THE HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY U.S.A. 8 1999 HDSUSA E.R. Cross Award- Bob Ramsay DIVING HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA, 9 In the News S.E. ASIA 11 Hans Hass HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY CANADA 12 HDS and DEMA 2000. A Partnership for Growth HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY GERMANY 13 1999 DEMA Reaching Out Awards 14 Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences 1999 EDITORS NOGI Awards and History Leslie Leaney, Editor 15 HDSUSA Intern - Sammy Oziel Andy Lentz, Production Editor 16 In the Mail Steve Barsky, Copy Editor 17 DHSASEA Annual Rally in Adelaide 18 HDS Canada. -

A VOICE in the WILDERNESS: Listening to the Statement from the Heart Author: Celia Kemp, Reconciliation Coordinator | Artist: the Reverend Glenn Loughrey

A VOICE IN THE WILDERNESS: Listening to the Statement from the Heart Author: Celia Kemp, Reconciliation Coordinator | Artist: The Reverend Glenn Loughrey Foreword Listening is an important, if not dying, art form. Being able to hear the First published November 2018 Second printing with minor updates, June 2019 voice of the other is deeply challenging. It seems to me, at least, that many ISBN: 978-0-6483444-0-7 Australians wish to hear the voice of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. They truly want to hear what is on our hearts. Yet, at the same Free pdf version, Leader’s Guide or time there are some whose hearts have turned cold, and do not wish to to order hard copies: www.abmission.org/voice listen to anything but their own voices. ‘The Statement from the Heart’ is an important voice for the aspirations and hopes of the First Nations peoples of our land. It deserves to be heard by ABM is a non-profit organisation. many, and for those who have stopped their ears it could become a chance for ‘hearts of stone to be turned into hearts of flesh.’ (Ezekiel 36: 26). This Study has been made possible by donors who support ABM’s ‘Voice in the wilderness: Listening to the Statement of the Heart’ is the creation of loving listening by Celia Kemp; encouraging the Church to stop Reconciliation work. We especially and listen. This study also gifts us with the opportunity to ‘listen’ to the art acknowledge the generous support of Glenn Loughrey, a Wiradjuri man and Anglican Priest; the penetrating of the Society of the Sacred Mission voice of sight, colour and image. -

Idstorical Diver

Historical Diver, Number 3, 1994 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 11/10/2021 02:43:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30846 IDSTORICAL DIVER Number 3 Summer 1994 The Official Publication of the Historical Diving Society U.S.A As you will by now know, the Society has relocated to Santa Barbara, California and this move, along with various other Society developments has delayed the publication of the Spring '94 issue of HISTORICAL DIVER. By way of catching up, we have produced a Summer double issue and have the good fortune to be able to publish with a color cover. Coinciding with the Santa Barbara relocation is the appointment, by the Board of Directors, of the first members of the HDS USA Advisory Board. This distinguished group of senior diving professionals, with extensive backgrounds in diving medicine, technical development, commercial, military and sports diving, bring in excess of 300 years of diving experience to the Society. Most of their biographies are the size of town phone directories, and have had to be severely edited for publication. We are honored and gratefulfortheir willing offers of service, and hope that we have done their biographies justice. Details start on page 4. The recently introduced, Founding Benefactor class of membership has proven to be very popular with over half of the thirty available memberships already taken. An opportunity still exists to acquire one of these unique memberships and details of it's benefits are noted on page 9. On the international front, the ongoing formation of the HDS USA as a nonprofit corporation has, by law, changed the conditions that govern our relationship with the HDS in UK. -

Deanes Diving Manual

DEANE'S 1836 MANUAL METHOD OF USING THE DIVING APPARATUS, &C. This small book is the forerunner of all publications on the practice ofdiving and underwater safety. It was written by The Patent portable and highly approved Diving Ap- the inventors of the open diving dress and it is reproduced be- paratus, invented by Messrs. Charles Anthony and John Deane, low in it's entirety. which they have used with so much success on the wrecks of several of Her Majesty's, and many other Ships, and which they have now in operation on the wrecks of the Royal George and Mary Rose, (the latter ship was sunk at Spithead, during an engagement with a formidable French fleet, in the year 1544, whilst defending PORTSMOUTH,) will be found to be very valuable in all submarine researches, in discovering sunken property, surveying wrecks, or sunken ships and vessels - as also the Foundations of Harbours, Piers, Docks, Bridges, &c. &c.&c. A person equipt in this Apparatus, being enabled to de- scend to a considerable depth, from 20 fathoms, probably to 30, and to remain down several hours, (Mr. John Deane contin- ued under water at one time, for the space of five hours and forty minutes,) having the perfect use of his hands and legs, is freely enabled to traverse the bottom of the sea, and to search out the hidden treasures of the deep. Whenever it is intended to work in a Channel or Tideway, the Boat or Vessel containing the Diving Apparatus, with about seven men, should be moored over the intended object, with two or more anchors, to prevent the wind or the returning tide from shifting the Boat off the spot. -

The Messenger

Autumn 2019 The Messenger use your smartphone to visit our website! Previous versions of The Messenger are also available on-line at www.middlewall.co.uk the magazine of Whitstable Baptist Church Middle Wall Printed by the University of Kent’s Design & Print Centre. Design & Print Useful Contact Details BMS Birthday Scheme: June Gluning 771187 [email protected] Book Keeper: Janet Payne 264186 [email protected] Article ................................................. Page A Candle For Peace ...................................... 3 Choral Group: A Cowboy’s 10 Commandments ............... 17 Ray Jones 772997 [email protected] A Letter From Heaven ................................. 6 Church Flowers: Another Whitstable Trade ......................... 16 Pam Tyler 277624 [email protected] Answers to Quiz ......................................... 22 Autumn Leaves .......................................... 15 Deacons: Andrew Frame (Secretary) 794489 [email protected] Beryl’s Back! (page) ................................... 24 Cheree Moyes 638841 [email protected] … Birthday Greetings ..................................... 23 Jean Myhill 277297 [email protected] Catching Lives ............................................ 12 Alison Oliver 652953 [email protected] Contact Information ................................. ibc Messenger: Cover Picture ............................................... 2 Tony & Beryl Harris 780969 [email protected] I will live my life ........................................