'Enhanced Interrogation Techniques' In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

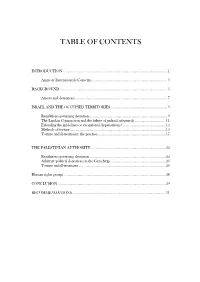

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. -

Sec 5.1~Abuse of Prisoners As Torture

1 5. Substantive Legal Assessment 5.1 Abuse of Prisoners as Torture and War Crimes under Sec. 8 of the CCIL and International Law The crimes described above against detainees at Abu Ghraib and the plaintiffs al Qahtani and Mowsboush constitute torture and war crimes under German and international criminal law. Therefore, sufficient evidence exists of criminality under Sec. 8 I nos. 3 and 9 CCIL. The following will provide a detailed legal analysis of the prohibitions in the CCIL and international law that were violated by the above-described acts. First, it will note the way in which two high-ranking members of the U.S. government dealt with the traditional torture techniques of “water boarding” and “longtime standing,” which is significant from the plaintiff’s perspective. In their publicly documented statements, both of government officials reveal a high degree of cynicism, coupled with ignorance of historical, legal and medical contexts. “Water Boarding” and “Longtime Standing” In the course of an interview on 24 October 2006, the Vice President of the United States, Richard Cheney, asked by radio reporter Scott Hennen whether “a dunk in water is a no- brainer if it can save lives,” gave the following answer: “It's a no-brainer for me, but for a 2 while there, I was criticized as being the ‘Vice President for torture.’ We don't torture. That's not what we're involved in. We live up to our obligations in international treaties that we're party to.” Cheney was the first member of the Bush government to admit that “water boarding” had been used in the case of detainee Khalid Scheikh Mohammed and other high-ranking al Quaeda members. -

Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 33 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 2008 Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Ingrid Detter Frankopan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Ingrid D. Frankopan, Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War, 33 N.C. J. INT'L L. 657 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol33/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol33/ iss4/3 Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Ingrid Detter Frankopant I. Introduction ....................................................................... 657 II. O rdinary R endition ............................................................ 658 III. Deportation, Extradition and Extraordinary Rendition ..... 659 IV. Essential Features of Extraordinary Rendition .................. 661 V. Extraordinary Rendition and Rfoulement ........................ 666 VI. Relevance of Legal Prohibitions of Torture ...................... 667 VII. Torture Flights, Ghost Detainees and Black Sites ............. 674 VIII. Legality -

Torture Flights : North Carolina’S Role in the Cia Rendition and Torture Program the Commission the Commission

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 LIST OF COMMISSIONERS 4 FOREWORD Alberto Mora, Former General Counsel, Department of the Navy 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Summary of the investigation into North Carolina’s involvement in torture and rendition by the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture (NCCIT) 8 FINDINGS 12 RECOMMENDATIONS CHAPTER ONE 14 CHAPTER SIX 39 The U.S. Government’s Rendition, Detention, Ongoing Challenges for Survivors and Interrogation (RDI) Program CHAPTER SEVEN 44 CHAPTER TWO 21 Costs and Consequences of the North Carolina’s Role in Torture: CIA’s Torture and Rendition Program Hosting Aero Contractors, Ltd. CHAPTER EIGHT 50 CHAPTER THREE 26 North Carolina Public Opposition to Other North Carolina Connections the RDI Program, and Officials’ Responses to Post-9/11 U.S. Torture CHAPTER NINE 57 CHAPTER FOUR 28 North Carolina’s Obligations under Who Were Those Rendered Domestic and International Law, the Basis by Aero Contractors? for Federal and State Investigation, and the Need for Accountability CHAPTER FIVE 34 Rendition as Torture CONCLUSION 64 ENDNOTES 66 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 78 APPENDICES 80 1 WWW.NCTORTUREREPORT.ORG TORTURE FLIGHTS : NORTH CAROLINA’S ROLE IN THE CIA RENDITION AND TORTURE PROGRAM THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION FRANK GOLDSMITH (CO-CHAIR) JAMES E. COLEMAN, JR. PATRICIA MCGAFFAGAN DR. ANNIE SPARROW MBBS, MRCP, FRACP, MPH, MD Frank Goldsmith is a mediator, arbitrator and former civil James E. Coleman, Jr. is the John S. Bradway Professor Patricia McGaffagan worked as a psychologist for twenty rights lawyer in the Asheville, NC area. Goldsmith has of the Practice of Law, Director of the Center for five years at the Johnston County, NC Mental Health Dr. -

A Plan to Close Guantánamo and End the Military Commissions Submitted to the Transition Team of President-Elect Obama From

A Plan to Close Guantánamo and End the Military Commissions submitted to the Transition Team of President-elect Obama from the American Civil Liberties Union Anthony D. Romero Executive Director 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004 (212) 549-2500 January 2009 HOW TO CLOSE GUANTÁNAMO: A PLAN Introduction Guantánamo is a scourge on America and the Constitution. It must be closed. This document outlines a five-step plan for closing Guantánamo and restoring the rule of law. Secrecy and fear have distorted the facts about Guantánamo detainees. Our plan is informed by recognition of the following critical facts, largely unknown to the public: • The government has quietly repatriated two-thirds of the 750 detainees, tacitly admitting that many should never have been held at all. • Most of the remaining detainees will not be charged as terrorists, and can be released as soon as their home country or a haven country agrees to accept them. • Trying the remaining detainees in federal court – and thus excluding evidence obtained through torture or coercion – does not endanger the public. The rule of law and the presumption of innocence serve to protect the public. Furthermore, the government has repeatedly stated that there is substantial evidence against the detainees presumed most dangerous – the High Value Detainees – that was not obtained by torture or coercion. They can be brought to trial in federal court. I. Step One: Stay All Proceedings of the Military Commissions and Impose a Deadline for Closure The President should immediately -

Outlawed: Extraordinary Rendition, Torture and Disappearances in the War on Terror

Companion Curriculum OUTLAWED: Extraordinary Rendition, Torture and Disappearances in the War on Terror In Plain Sight: Volume 6 A WITNESS and Amnesty International Partnership www.witness.org www.amnestyusa.org Table of Contents 2 Table of Contents How to Use This Guide HRE 201: UN Convention against Torture Lesson One: The Torture Question Handout 1.1: Draw the Line Handout 1.2: A Tortured Debate - Part 1 Handout 1.3: A Tortured Debate - Part 2 Lesson Two: Outsourcing Torture? An Introduction to Extraordinary Rendition Resource 2.1: Introduction to Extraordinary Rendition Resource 2.2: Case Studies Resource 2.3: Movie Discussion Guide Resource 2.4: Introduction to Habeas Corpus Resource 2.5: Introduction to the Geneva Conventions Handout 2.6: Court of Human Rights Activity Lesson Three: Above the Law? Limits of Executive Authority Handout 3.1: Checks and Balances Timeline Handout 3.2: Checks and Balances Resource 3.3: Checks and Balances Discussion Questions Glossary Resources How to Use This Guide 3 How to Use This Guide The companion guide for Outlawed: Extraordinary Rendition, Torture, and Disappearances in the War on Terror provides activities and lessons that will engage learners in a discussion about issues which may seem difficult and complex, such as federal and international standards regarding treatment of prisoners and how the extraordinary rendition program impacts America’s success in the war on terror. Lesson One introduces students to the topic of torture in an age appropriate manner, Lesson Two provides background information and activities about extraordinary rendition, and Lesson Three examines the limits of executive authority and the issue of accountability. -

Lawfulness of Interrogation Techniques Under the Geneva Conventions

Order Code RL32567 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Lawfulness of Interrogation Techniques under the Geneva Conventions September 8, 2004 Jennifer K. Elsea Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Lawfulness of Interrogation Techniques under the Geneva Conventions Summary Allegations of abuse of Iraqi prisoners by U.S. soldiers at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq have raised questions about the applicability of the law of war to interrogations for military intelligence purposes. Particular issues involve the level of protection to which the detainees are entitled under the Geneva Conventions of 1949, whether as prisoners of war or civilian “protected persons,” or under some other status. After photos of prisoner abuse became public, the Defense Department (DOD) released a series of internal documents disclosing policy deliberations about the appropriate techniques for interrogating persons the Administration had deemed to be “unlawful combatants” and who resisted the standard methods of questioning detainees. Investigations related to the allegations at Abu Ghraib revealed that some of the techniques discussed for “unlawful combatants” had come into use in Iraq, although none of the prisoners there was deemed to be an unlawful combatant. This report outlines the provisions of the Conventions as they apply to prisoners of war and to civilians, and the minimum level of protection offered by Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. There follows an analysis of key terms that set the standards for the treatment of prisoners that are especially relevant to interrogation, including torture, coercion, and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, with reference to some historical war crimes cases and cases involving the treatment of persons suspected of engaging in terrorism. -

Twenty-Third Annual Hooding of Candidates for the Degree of Juris

I n n j I I il 1 :i Southern Methodist T-Iniversity o ! School of Lan¡ Twenfy-third Annual Hooding of Candidates for the Degree of Juris Doctor and ¡ Presentation of Candidates i for Other Degrees i 1 Saturday Evening, the Twenty-first of May i Nineteen Hundred and Ninety-four at Six-thirry O'clock UL) Law School Quadrangle ii \ \øELCOME TO SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY ''lrHoot oF L,{\(/ Southern Methodist University opened in the fall of l9I5 and graduated its first class in the spring of 1916. This is the University's 79th Annual Commencement Convocation. The School of Law ar Southern Methodist University was established in February 1925. k is a member of the Association of American Law Schools and is approved by the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar of the American Bar Association. The Êrst law school class graduated in 1928 with 11 members. This, the 67th graduating class,consists of2S2candidatesfortheJurisDoctordegtee,3T candidatesfortheMasteroflaws degree (Comparative and International Law), and 15 candidates for the Master of Laws degree. There are four buildings in the Law School Quadrangle. Storey Hall houses the faculty library, faculty and administrative offrces, the Legal Clinic, School ofLaw publications, and Karcher Auditorium. Carr Collins Hall, formerly Lawyers Inn, was recently renovated and contains two state-of-the-art seminar classrooms; student lounge and student areas; the of6ces ofA.dmissions, Career Services, Public Service Program, and Student.Affairs; as well as other University offices. Florence Hall is the classroom building with a model law offrce and courtroom facilities having modern audiovisual equipment and closed-circuit television. -

Torture, Surrogacy, and the US War on Terror

Societies Without Borders Volume 7 | Issue 3 Article 2 2012 Indirect Violence and Legitimation: Torture, Surrogacy, and the U.S. War on Terror Eric Bonds University of Mary Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bonds, Eric. 2012. "Indirect Violence and Legitimation: Torture, Surrogacy, and the U.S. War on Terror." Societies Without Borders 7 (3): 295-325. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol7/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Societies Without Borders by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Bonds: Indirect Violence and Legitimation: Torture, Surrogacy, and the U E. Bonds/Societies Without Borders 7:3 (2012) 295-325 Indirect Violence and Legitimation: Torture, Surrogacy, and the U.S. War on Terror Eric Bonds University of Mary Washington Received February 2012; Accepted April 2012 ______________________________________________________ Abstract This paper contributes to the sociological study of legitimation, specifically focusing on the state legitimation of torture and other forms of violence that violate international normative standards. While sociologists have identified important discursive techniques of legitimation, this paper suggests that researchers should also look at state practices where concerns regarding legitimacy are “built in” to the very practice of certain forms of violence. Specifically, the paper focuses on surrogacy, through which powerful states may direct or benefit from the violence carried out by client states or other armed groups while at the same time attempting to appear separate from and blameless regarding any resulting human rights violations. -

Seven Myths About UK Military Abuses Against Civilians in Iraq

Seven myths about UK military abuses against civilians in Iraq 1. “The abuses were carried out by a few bad apples.” The UK Ministry of Defence has approved payments totalling £20 million to settle 331 cases of violations committed by UK service personnel against Iraqi nationals in Iraq.1 The former chief legal adviser to the British Army in Iraq has written that the pattern of abuse during interrogation of detainees ‘appears systematic’. In particular, the use of the ‘five techniques’ (hooding, stress positions, white noise, sleep deprivation, and deprivation of food and drink), banned under UK law since the 1970s and since found by the Belfast Court of Appeal to constitute torture, was alleged to be widespread. Some 600 further cases before the courts alleging abuse against Iraqi civilians are yet to be resolved. 2. “The investigations are a witch hunt.” Far from being imaginary or exaggerated for political reasons, the abuses for which UK forces have been held responsible represent serious violations of fundamental rights, including killing, false imprisonment and inhuman and degrading treatment. In perhaps the most well-known case, Mr Baha Mousa, a hotel receptionist in Basra, was beaten to death over the course of 36 hours in detention, the autopsy recording 93 separate injuries.2 Mr Nadheem Abdullah, another civilian, was dragged from the passenger seat of a taxi, and beaten to the ground, dying from a blow from a rifle butt to the back of his head.3 In four test cases decided at the High Court in December 2017, four civilians were awarded damages for unlawful detention, beating (including with rifle butts, to the back and head), sensory and sleep deprivation, and other inhuman and degrading treatment, including in one case being made to lie prone while soldiers repeatedly ran over the victim’s back.4 3. -

Law School Announcements 2020-2021

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications Fall 2020 Law School Announcements 2020-2021 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 2020-2021" (2020). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. 133. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/133 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements Fall 2020 Effective Date: September 1, 2020 This document is published on September 1 and its contents are not updated thereafter. For the most up-to-date information, visit www.law.uchicago.edu. 2 The Law School Contents OFFICERS AND FACULTY ........................................................................................................ 6 Officers of Administration ............................................................................................ 6 Officers of Instruction ................................................................................................... 6 Lecturers in Law .........................................................................................................