F:\...\05 Levit Master C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

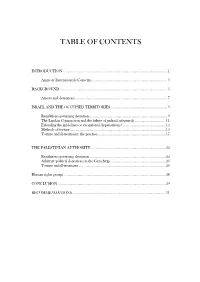

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) During the Administrations of Presidents George W

Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) During the Administrations of Presidents George W. Bush, Barack H. Obama, and Donald J. Trump: In Brief May 24, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46798 Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 2 Tables Table 1. George W. Bush Administration-era Nominees for IC PAS Positions............................... 2 Table 2. Obama Administration-era Nominees for IC PAS Positions ............................................. 5 Table 3. Trump Administration Nominees for IC PAS Positions .................................................... 7 Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 10 Congressional Research Service Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) Introduction This report provides three tables that list the names of those who have served in presidentially appointed, Senate-confirmed (PAS) positions in the Intelligence Community (IC) during the last twenty years. It provides a comparative perspective of both those holding IC PAS positions who have -

Achievement Awards

The 3RD Annual INSA Achievement Awards December 6, 2012 INTELLIGENCE AND NATIONAL SECURITY ALLIANCE AboutA INSA Program Agenda INSA is the premier intelligence and national security organization that Reception brings together the public, private and academic sectors to collaborate Cocktails and Networking on the most challenging policy issues and solutions. As a non-profit, non-partisan, public-private organization, INSA’s ultimate goal is to promote and recognize the highest standards within the national security Welcome and intelligence communities. INSA has over 150 corporate members Chuck Alsup, INSA Acting President and several hundred individual members who are leaders and senior executives throughout government, the private sector and academia. To learn more about INSA visit www.insaonline.org. Keynote Address Letitia A. Long, Director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Building a Stronger Intelligence Community Dinner Presentation of 2012 INSA Achievement Awards Thank You We would like to thank the following organizations for their table purchases: Eagle Sponors General Dynamics Raytheon Company Liberty Sponsor ITT Exelis Northrop Grumman Corporation Select Tables Accenture KEYW Corporation MITRE Corporation Oracle Penn State University – Applied Research Lab TASC The SI Organization, Inc. 2 3 INSA Achievement Awards Keynote Speaker Purpose Letitia A. Long, Director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency The Intelligence and National Security Alliance (INSA) established a Ms. Letitia A. Long was appointed series of awards in 2010 intended to recognize the achievements of Director of the National Geospatial- young professionals in intelligence and national security. Six awards are Intelligence Agency on August 9, named after previous William Oliver Baker Award recipients and are 2010. -

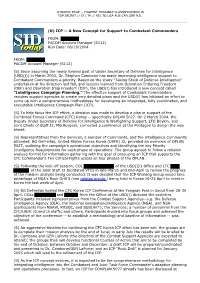

ICP -- a New Concept for Support to Combatant Commanders

DYNAMIC PAGE -- HIGHEST POSSIBLE CLASSIFICATION IS TOP SECRET // SI / TK // REL TO USA AUS CAN GBR NZL (U) ICP -- A New Concept for Support to Combatant Commanders FROM: PACOM Account Manager (S112) Run Date: 06/18/2004 FROM: PACOM Account Manager (S112) (S) Since assuming the newly formed post of Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence (USD(I)) in March 2003, Dr. Stephen Cambone has made improving intelligence support to Combatant Commanders a priority. Based on the study "Taking Stock of Defense Intelligence" undertaken at his direction last fall, and lessons learned from Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), the USD(I) has introduced a new concept called "Intelligence Campaign Planning." The effective support of Combatant Commanders requires support agencies to create very detailed plans and the USD(I) has initiated an effort to come up with a comprehensive methodology for developing an integrated, fully coordinated, and executable Intelligence Campaign Plan (ICP). (S) To help focus the ICP effort, a decision was made to develop a plan in support of the Combined Forces Command (CFC) Korea -- specifically OPLAN 5027. On 2 March 2004, the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence & Warfighting Support, LTG Boykin, and Joint Chiefs of Staff J2, MG Burgess, co-hosted a conference at the Pentagon to design the way ahead. (S) Representatives from the Services, a number of Commands, and the Intelligence Community attended. BG DeFreitas, United States Forces Korea (USFK) J2, provided an overview of OPLAN 5027, outlining the campaign's operational objectives and identifying the key Priority Intelligence Requirements for each phase of operations. -

Speaker Bios

Intelligence Reform and Counterterrorism after a Decade: Are We Smarter and Safer? October 16 – 18, 2014 University of Texas at Austin THURSDAY, OCTOBER 16 Blanton Museum, UT Campus 4:00-5:00pm Welcome Remarks and Discussion: Admiral William McRaven (ret.) Admiral McRaven is the ninth commander of United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base, Fla. USSOCOM ensures the readiness of joint special operations forces and, as directed, conducts operations worldwide. McRaven served from June 2008 to June 2011 as the 11th commander of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) headquartered at Fort Bragg, N.C. JSOC is charged to study special operations requirements and techniques, ensure interoperability and equipment standardization, plan and conduct special operations exercises and training, and develop joint special operations tactics. He served from June 2006 to March 2008 as commander, Special Operations Command Europe (SOCEUR). In addition to his duties as commander, SOCEUR, he was designated as the first director of the NATO Special Operations Forces Coordination Centre where he was charged with enhancing the capabilities and interoperability of all NATO Special Operations Forces. McRaven has commanded at every level within the special operations community, including assignments as deputy commanding general for Operations at JSOC; commodore of Naval Special Warfare Group One; commander of SEAL Team Three; task group commander in the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility; task unit commander during Desert Storm and Desert Shield; squadron commander at Naval Special Warfare Development Group; and SEAL platoon commander at Underwater Demolition Team 21/SEAL Team Four. His diverse staff and interagency experience includes assignments as the director for Strategic Planning in the Office of Combating Terrorism on the National Security Council Staff; assessment director at USSOCOM, on the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations, and the chief of staff at Naval Special Warfare Group One. -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. -

Critical Infrastructure Report

AUTHORED BY: TIFFANY EAST ER ADAM EATON HALEY EWING TREY GREEN CHRIS GRIFFIN CHANDLER LEWIS KRISTINA MILLIGAN KERI WEINMAN ADVISOR: DR. DANNY DAVIS 2018-2019 CAPSTONE PROJECT CLIENT: POINTSTREAM, INC. COMPREHENSIVE U.S. CYBER FRAMEWORK KEY ASPECTS OF CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE, PRIVATE SECTOR, AND PERSONALLY IDENTIFIABLE INFORMATION 2018 – 2019 Capstone Team The Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University Advisor: Danny W. Davis, Ph.D. About the Project This project is a product of the Class of 2019 Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University Capstone Program. The project lasted one academic year and involved eight second-year master students. It intends to synthesize and provide clarity in the realm of issues pertaining to U.S. Internet Protocol Space by demonstrating natural partnerships and recommendations for existing cyber incident response. The project was produced at the request of PointStream Inc., a private cybersecurity contractor. Mission This capstone team analyzed existing frameworks for cyber incident response for PointStream Inc. in order to propose a comprehensive and efficient plan for U.S. cybersecurity, critical infrastructure, and private sector stakeholders. Advisor Dr. Danny Davis - Associate Professor of the Practice and Director, Graduate Certificate in Homeland Security Capstone Team Tiffany Easter - MPSA 2019 Adam Eaton - MPSA 2019 Haley Ewing - MPSA 2019 Trey Green - MPSA 2019 Christopher Griffin - MPSA 2019 Chandler Lewis - MPSA 2019 Kristina Milligan - MPSA 2019 Keri Weinman - MPSA 2019 Acknowledgement The Capstone Team would like to express gratitude to COL Phil Waldron, Founder and CEO of PointStream Inc., for this opportunity and invaluable support throughout the duration of this project. -

Perspectives and Opportunities in Intelligence for U.S. Leaders

Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE September 2018 CORTNEY WEINBAUM, JOHN V. PARACHINI, RICHARD S. GIRVEN, MICHAEL H. DECKER, RICHARD C. BAFFA Perspectives and Opportunities in Intelligence for U.S. Leaders C O R P O R A T I O N Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 2. Reconstituting Strategic Warning for the Digital Age .................................5 3. Unifying Tasking, Collection, Processing, Exploitation, and Dissemination (TCPED) Across the U.S. Intelligence Community ...............16 4. Managing Security as an Enterprise .........................................................25 5. Better Utilizing Publicly Available Information ..........................................31 6. Surging Intelligence in an Unpredictable World .......................................44 7. Conclusion .................................................................................................56 Abbreviations ................................................................................................57 References ....................................................................................................58 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................64 About the Authors .........................................................................................64 The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make -

Sec 5.1~Abuse of Prisoners As Torture

1 5. Substantive Legal Assessment 5.1 Abuse of Prisoners as Torture and War Crimes under Sec. 8 of the CCIL and International Law The crimes described above against detainees at Abu Ghraib and the plaintiffs al Qahtani and Mowsboush constitute torture and war crimes under German and international criminal law. Therefore, sufficient evidence exists of criminality under Sec. 8 I nos. 3 and 9 CCIL. The following will provide a detailed legal analysis of the prohibitions in the CCIL and international law that were violated by the above-described acts. First, it will note the way in which two high-ranking members of the U.S. government dealt with the traditional torture techniques of “water boarding” and “longtime standing,” which is significant from the plaintiff’s perspective. In their publicly documented statements, both of government officials reveal a high degree of cynicism, coupled with ignorance of historical, legal and medical contexts. “Water Boarding” and “Longtime Standing” In the course of an interview on 24 October 2006, the Vice President of the United States, Richard Cheney, asked by radio reporter Scott Hennen whether “a dunk in water is a no- brainer if it can save lives,” gave the following answer: “It's a no-brainer for me, but for a 2 while there, I was criticized as being the ‘Vice President for torture.’ We don't torture. That's not what we're involved in. We live up to our obligations in international treaties that we're party to.” Cheney was the first member of the Bush government to admit that “water boarding” had been used in the case of detainee Khalid Scheikh Mohammed and other high-ranking al Quaeda members. -

MICROCOMP Output File

S. HRG. 106±144 NATO'S 50TH ANNIVERSARY SUMMIT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 21, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 58±335 CC WASHINGTON : 1999 VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:44 Sep 20, 1999 Jkt 549297 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 58335 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee JAMES W. NANCE, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:44 Sep 20, 1999 Jkt 549297 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 58335 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 CONTENTS Page Cambone, Dr. Stephen A., research director, Institute for National Security Studies, National Defense University, Washington, DC .................................. 32 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 45 Grossman, Hon. Marc, Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs ......... 14 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 50 Hadley, Hon. Stephen, partner, Shea and Gardner, Washington, DC ................ 31 Kramer, Hon. Franklin D., Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs .................................................................................................... 19 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 53 Kyl, Hon. Jon, U.S. -

Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 33 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 2008 Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Ingrid Detter Frankopan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Ingrid D. Frankopan, Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War, 33 N.C. J. INT'L L. 657 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol33/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol33/ iss4/3 Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Ingrid Detter Frankopant I. Introduction ....................................................................... 657 II. O rdinary R endition ............................................................ 658 III. Deportation, Extradition and Extraordinary Rendition ..... 659 IV. Essential Features of Extraordinary Rendition .................. 661 V. Extraordinary Rendition and Rfoulement ........................ 666 VI. Relevance of Legal Prohibitions of Torture ...................... 667 VII. Torture Flights, Ghost Detainees and Black Sites ............. 674 VIII. Legality -

Congressional Record—House H3071

May 17, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H3071 emergency room, you do not have to This is not on the back of the doc- with regard to an employer filing of a give them extensive treatment for dis- tors. The doctors are freed from re- notice of contest following the issuance eases that are not at that moment life- sponsibility on that, because they no of a citation by the Occupational Safe- threatening. longer have to treat anything, unless ty and Health Administration; for con- Thus, they will take care of an illegal someone’s life is threatened at that sideration of the bill (H.R. 2729) to whose life is being threatened, but they moment. amend the Occupational Safety and will not have to take care and spend Let me add one other thing. If they Health Act of 1970 to provide for great- $300,000 or $400,000 for cancer treat- do treat an illegal immigrant in an er efficiency at the Occupational Safe- ments, and this happens, for all types emergency situation, my bill insists ty and Health Review Commission; for of transplants of organs, for hundreds that we go to the employer, because consideration of the bill (H.R. 2730) to of thousands and millions of dollars that is the only question that hospital amend the Occupational Safety and worth of health care that illegals are has to ask, who is your employer? And Health Act of 1970 to provide for an getting right now. if that employer has not done due dili- independent review of citations issued My bill says they do not have to do gence to see if he is hiring an illegal by the Occupational Safety and Health that.