Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the Honorable Members of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Organization of American States

TO THE HONORABLE MEMBERS OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS, ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES ______________________________________________________________ PETITION ALLEGING VIOLATIONS OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF KHALED EL-MASRI BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WITH A REQUEST FOR AN INVESTIGATION AND HEARING ON THE MERITS By the undersigned, appearing as counsel for petitioner under the provisions of Article 23 of the Commission’s Regulations __________________________ Steven Macpherson Watt Jamil Dakwar Jennifer Turner Melissa Goodman Ben Wizner Human Rights & ٭ National Security Programs American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY, 10004 Ph: (212) 519-7870 ,Counsel gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Kristen Bailey, LL.M. student ٭ New York University Law School, in compiling this petition. Submitted: April 9, 2008 INTRODUCTION This petition is brought against the United States of America for violating the rights of Khaled El-Masri, a German citizen and victim of the U.S. “extraordinary rendition” program. In December 2003, while on vacation in Macedonia, Mr. El-Masri was apprehended and detained by agents of the Macedonian intelligence services. While in their custody, Mr. El-Masri was harshly interrogated. His repeated requests to meet with a lawyer, family members, and a consular representative were denied. After twenty-three days of such treatment, Mr. El-Masri was handed over to the exclusive “authority and control” of agents of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. These agents beat, stripped, and drugged Mr. El-Masri before loading him onto a plane and flying him to a secret CIA- run prison in Afghanistan. There, Mr. El-Masri was detained incommunicado for more than four months. -

Annual Renewal of Control Orders Legislation 2010

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Counter–Terrorism Policy and Human Rights (Sixteenth Report): Annual Renewal of Control Orders Legislation 2010 Ninth Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes, and oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 23 February 2010 Ordered by The House of Lords to be printed 23 February 2010 HL Paper 64 HC 395 Published on Friday 26 February 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders made under Section 10 of and laid under Schedule 2 to the Human Rights Act 1998; and in respect of draft remedial orders and remedial orders, whether the special attention of the House should be drawn to them on any of the grounds specified in Standing Order No. 73 (Lords)/151 (Commons) (Statutory Instruments (Joint Committee)). The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is three from each House. Current membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) (Chairman) Lord Dubs Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Baroness Falkner of Margravine Abingdon) Lord Morris of Handsworth OJ Ms Fiona MacTaggart (Labour, Slough) The Earl of Onslow Mr Virendra Sharma MP (Labour, Ealing, Southall) Baroness Prashar Mr Richard Shepherd MP (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Mr Edward Timpson MP (Conservative, Crewe & Nantwich) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

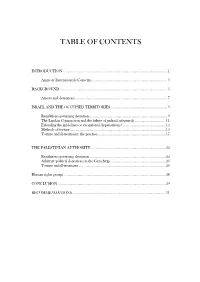

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

Conflict, Security and the Reshaping of Society: the Civilization of War Dal Lago, Alessandro (Ed.); Palidda, Salvatore (Ed.)

www.ssoar.info Conflict, security and the reshaping of society: the civilization of war Dal Lago, Alessandro (Ed.); Palidda, Salvatore (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerk / collection Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Dal Lago, A., & Palidda, S. (Eds.). (2010). Conflict, security and the reshaping of society: the civilization of war (Routledge Studies in Liberty and Security). London: Taylor & Francis. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-273834 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Conflict, Security and the Reshaping of Society This book is an examination of the effect of contemporary wars (such as the ‘War on Terror’) on civil life at a global level. Contemporary literature on war is mainly devoted to recent changes in the theory and practice of warfare, particularly those in which terrorists or insurgents are involved (for example, the ‘revolution in military affairs’, ‘small wars’, and so on). On the other hand, today’s research on security is focused, among other themes, on the effects of the war on terrorism, and on civil liberties and social control. This volume connects these two fields of research, showing how ‘war’ and ‘security’ tend to exchange targets and forms of action as well as personnel (for instance, the spreading use of private contractors in wars and of military experts in the ‘struggle for security’) in modern society. -

Extraordinary Rendition: a One-Way Ticket to the U.S

Catholic University Law Review Volume 41 Issue 1 Fall 1991 Article 9 1991 Extraordinary Rendition: A One-Way Ticket to the U.S.... Or Is It? Jacqueline A. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Jacqueline A. Weisman, Extraordinary Rendition: A One-Way Ticket to the U.S.... Or Is It?, 41 Cath. U. L. Rev. 149 (1992). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol41/iss1/9 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION: A ONE-WAY TICKET TO THE U.S.... OR IS IT? A treaty is an agreement or contract between two or more sovereigns or nations,1 signed and ratified by the states' lawmaking authorities.2 In the United States, the President has the power "by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur."3 The United States Constitution declares that a treaty is the law of the land,4 and a treaty is regarded by the courts as equivalent to a statute. 5 If a treaty and a statute are inconsistent, the last in time will pre- vail.6 Treaties are also a source of international law and bind the signatory parties to carry out their obligations.7 Extradition is a formal process through which a person is surrendered by one state to another by virtue of a treaty.' The person surrendered is usually a fugitive from justice wanted for prosecution or sentencing in the requesting country for a crime committed there. -

The Abu Omar Case in Italy: 'Extraordinary Renditions'

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kent Academic Repository The Abu Omar Case in Italy: ‘Extraordinary Renditions’ and State Obligations to Criminalize and Prosecute Torture under the UN Torture Convention Francesco Messineo * [This is the pre-print version of a paper accepted for publication in the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Vol. 7 (2009). Published by Oxford University Press.] 1. Introduction On 12 February 2003, at around 12.30 p.m., Mr Osama Mustafa Hassan Nasr (Abu Omar) was walking from his house in Milan to the local Mosque. He was stopped by a plain-clothes carabiniere (Italian military police officer) who asked for his documents. While he was searching for his refugee passport, 1 he was immobilised and put into a white van by more plain-clothes officers, at least some of whom were US agents. He was brought to a US airbase in Aviano in North-East Italy and from there, flown via the US airbase in Ramstein (Germany) to Egypt. He was held for approximately seven months at the Egyptian military intelligence headquarters in Cairo, and later transferred to Torah prison. 2 His whereabouts were unknown for a long time, and he was allegedly repeatedly tortured. 3 He was released in April 2004, re-arrested in May 2004 and eventually subjected to a form of house arrest in Alexandria in February 2007. 4 In June 2007, a criminal trial started in Milan against US and Italian agents accused of having been involved in Abu * Dott. giur. (Catania), LL.M. (Cantab); PhD candidate, University of Cambridge. -

Egypt's Complicity in Torture and Extraordinary Renditions Nirmala Pillay* 1. Introduction Robert Baer, a Cia Agent, Exempl

CHAPTER TWELVE Egypt’s COMPLICITY IN TORTURE AND EXTRAORDINARY RENDITIONS Nirmala Pillay* 1. Introduction Robert Baer, a CIA agent, exemplified the importance of the Mubarak gov- ernment for US intelligence when he observed that “If you want serious interrogation you send a prisoner to Jordan, if you want them to be tor- tured, you send them to Syria. If you want someone to disappear . never to see them again . you send them to Egypt.”1 Hosni Mubarak enjoyed close ties with Western countries enabling the US, Canada, Britain, and Sweden to deport terrorist suspects to a regime that specialised in inter- rogation methods prohibited by international law. This chapter examines the implications of the fall of the Egyptian regime of Hosni Mubarak for the prohibition against torture, a jus cogens norm of international law. Torture theorist Darius Rejali argued in a major study, published in 1997, that torture was never really eliminated from democratic countries, so a change of regime in Egypt in favour of a demo- cratic form of governance is no guarantee that torture, an entrenched part of the Egyptian security regime, will necessarily abate. Rejali’s thesis is probed in the light of the revelations of extraordinary renditions of terror- ist suspects to Egypt and the implications of the Egyptian revolution for US and Egyptian collaboration in the “war on terror.” Extraordinary rendition is the practice of transferring terrorist sus- pects, “with the involvement of the US or its agents, to a foreign State in circumstances that make it more likely than not that the individual will be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.”2 This * School of Law, Liverpool John Moores University, UK. -

Extraordinary Rendition in U.S. Counterterrorism Policy: the Impact on Transatlantic Relations

EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION IN U.S. COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY: THE IMPACT ON TRANSATLANTIC RELATIONS JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EUROPE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 17, 2007 Serial No. 110–28 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 34–712PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS TOM LANTOS, California, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ROBERT WEXLER, Florida EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RON PAUL, Texas DIANE E. WATSON, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona ADAM SMITH, Washington JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee THADDEUS G. MCCOTTER, Michigan LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina DAVID WU, Oregon CONNIE MACK, Florida BRAD MILLER, North Carolina JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska LINDA T. -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. -

Torture by Proxy: International and Domestic Law Applicable to “Extraordinary Renditions”

TORTURE BY PROXY: INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC LAW APPLICABLE TO “EXTRAORDINARY RENDITIONS” The Committee on International Human Rights of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and The Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, New York University School of Law © 2004 ABCNY & CHRGJ, NYU School of Law New York, NY Association of the Bar of the City of New York The Association of the Bar of the City of New York (www.abcny.org) was founded in 1870, and since then has been dedicated to maintaining the high ethical standards of the profession, promoting reform of the law, and providing service to the profession and the public. The Association continues to work for political, legal and social reform, while implementing innovating means to help the disadvantaged. Protecting the public’s welfare remains one of the Association’s highest priorities. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice The Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) at NYU School of Law (http://www.nyuhr.org) focuses on issues related to “global justice,” and aims to advance human rights and respect for the rule of law through cutting-edge advocacy and scholarship. The CHRGJ promotes human rights research, education and training, and encourages interdisciplinary research on emerging issues in international human rights and humanitarian law. This report should be cited as: Association of the Bar of the City of New York & Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Torture by Proxy: International and Domestic Law Applicable to “Extraordinary Renditions” (New York: ABCNY & NYU School of Law, 2004). - This report was modified in June 2006 - The Association of the Bar of the City of New York Committee on International Human Rights Martin S. -

Alleged Secret Detentions and Unlawful Inter-State Transfers Involving Council of Europe Member States

Parliamentary Assembly Assemblée parlementaire restricted AS/Jur (2006) 16 Part II 7 June 2006 ajdoc16 2006 Part II Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers involving Council of Europe member states Draft report – Part II (Explanatory memorandum) Rapporteur: Mr Dick Marty, Switzerland, ALDE C. Explanatory memorandum by Mr Dick Marty, Rapporteur Table of Contents: 1. Are human rights little more than a fairweather option? ……………………………………. 3 1.1. 11 September 2001 ……………………………………………………………………… 3 1.2. Guantanamo Bay ………………………………………………………………………… 4 1.3. Secret CIA prisons in Europe?…………………………………………………………. 4 1.4. The Council of Europe’s response ……………………………………………………. 5 1.5. European Parliament ………………………………………………………………….. 6 1.6. Rapporteur or investigator? …………………………………………………………… 6 1.7. Is this an Anti-American exercise? ……………………………………………………. 7 1.8 Is there any evidence?............................................................................................ 8 2. The global “spider’s web”………………………………………………………………………. 9 2.1. The evolution of the rendition programme ……………………………………………. 9 2.2. Components of the spider’s web ………………………………………………………. 12 2.3. Compiling a database of aircraft movements ………………………………………… 14 2.4. Operations of the spider’s web ………………………………………………………… 15 2.5. Successive rendition operations and secret detentions …………………………….. 16 2.6. Detention facilities in Romania and Poland ……………………….. 16 2.6.1 The case of Romania …………………………………………………. 16 2.6.2. The case of Poland ……………………………………………………. 17 2.7. The human impact of rendition and secret detention ……………………………….. 19 2.7.1. CIA methodology – how a detainee is treated during a rendition ………… 20 2.7.2. The effects of rendition and secret detention on individuals ………………. and families ……………………………………………………………………… 23 ________________________ F œ 67075 Strasbourg Cedex, tel: +33 3 88 41 20 00, fax: +33 3 88 41 27 02, http://assembly.coe.int, e-mail: [email protected] AS/Jur (2006) 16 Part II 2 3. -

JMWP 05 Jones

New York University School of Law Jean Monnet Working Paper Series JMWP 05/15 Henry Jones “The World as It Is, Not as We’d like It To Be” - Thinking with the Sea about International Law Cover: Billy The Kid, 2000, Steven Lewis THE JEAN MONNET PROGRAM J.H.H. Weiler, Director Gráinne de Burca, Director Jean Monnet Working Paper 05/15 Henry Jones “The World as It Is, Not as We’d like It To Be”- Thinking with the Sea about International Law NYU School of Law • New York, NY 10011 The Jean Monnet Working Paper Series can be found at www.JeanMonnetProgram.org All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. ISSN 2161-0320 (online) Copy Editor: Danielle Leeds Kim © Henry Jones 2014 New York University School of Law New York, NY 10011 USA Publications in the Series should be cited as: AUTHOR, TITLE, JEAN MONNET WORKING PAPER NO./YEAR [URL] Thinking with the Sea about International Law “THE WORLD AS IT IS, NOT AS WE’D LIKE IT TO BE”1 – THINKING WITH THE SEA ABOUT INTERNATIONAL LAW. By Henry Jones∗ “La mer, la mer, toujours recommencee” (The sea, the sea, forever restarting) – Paul Valery, Le Cimetière Marin (The Graveyard by the Sea) Abstract This article examines the role of the sea in international law. The sea is a feature in several significant ways in international law, both in its history and its present. I argue that international law has developed its spatial elements in response to a perception of the ocean as a blank and empty space.